Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dmitry Blinov | + 2934 word(s) | 2934 | 2021-06-11 07:48:28 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | + 2930 word(s) | 2930 | 2021-06-11 08:47:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Blinov, D. Cerium-Containing N-Acetyl-6-Aminohexanoic Acid. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10766 (accessed on 14 January 2026).

Blinov D. Cerium-Containing N-Acetyl-6-Aminohexanoic Acid. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10766. Accessed January 14, 2026.

Blinov, Dmitry. "Cerium-Containing N-Acetyl-6-Aminohexanoic Acid" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10766 (accessed January 14, 2026).

Blinov, D. (2021, June 11). Cerium-Containing N-Acetyl-6-Aminohexanoic Acid. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10766

Blinov, Dmitry. "Cerium-Containing N-Acetyl-6-Aminohexanoic Acid." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 June, 2021.

Copy Citation

Cerium N-acetyl-6-aminohexanoate (laboratory name LHT-8-17) as a 10 mg/mL aqueous spray was used as wound experimental topical therapy. LHT-8-17 4 mg twice daily accelerated linear and planar wounds healing in animals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The formulation topical application depressed tissue TNF-a, IL-1b level, and oxidative reactions activity along with sustaining both IL-10 concentration and antioxidant capacity. LHT-8-17 induced Ki-67 positivity of fibroblasts and pro-keratinocytes, upregulated FGFR3 gene expression, and increased tissue vascularization. The formulation possessed anti-microbial property.

cerium-containing formulation

diabetic wound

toxicity

proliferation

micro-vessels

anti-microbial activity

1. Introduction

A therapeutic approach to diabetic wound healing is one of the most challenging problems nowadays [1]. Worldwide, diabetic foot ulcer as a most common diabetes mellitus (DM) complication has a deteriorating impact on humans and society due to quality of life stagnation, a high rate of disability, and financial and economic burdens. Epidemiological studies report about a 25% life-time risk of foot ulceration in the diabetic population with approximately 24% of all health care expenses related to diabetic foot complications [2][3][4].

Disturbances of skin integrity may occur as an outcome of the general disease course, traumatic injury or surgical manipulations. The type of metabolic disorder also plays a key role in diabetic wound development and progression [5]. Delay and difficulties in diabetic wound reparation are strongly associated with molecular, cellular, and tissue changes at different stages of the healing process. They involve particularities of inflammatory regulation, vascularization of newly-developing tissues, and cellular differentiation and growth [6][7][8]. Molecular signaling and cellular cooperation limit the timing of healing completion, orchestrate the direction of reparation (substitution or restitution), and determine both the structure and stability of the forming scar [7][8]. Bacterial contamination of skin defects advances the damage severity that needs additional intervention and care [9]. Hence, current treatment options for diabetic wound healing require multidisciplinary solutions including surgery and non-surgical applications. Topical application of pharmacological agents or formulation is used to treat inflammation, for reparation, and to prevent microbial contamination.

Cerium, a metal of the lanthanoid group, possesses a broad range of pharmacological properties [10][11]. As an oxide and an organic salt, it demonstrates antimicrobial and regenerative activity, especially in burning soft tissue damage [12][13][14]. Recent studies demonstrated the high potency of metal-containing compounds to control oxidative stress and modulate neurotransmission [15][16]. N-Acethyl-6-aminohexanoic (ε-aminocaproic) acid has long been known for its antifibrinolytic activity [17].

2. LHT-8-17 In Vivo Cell Toxicity

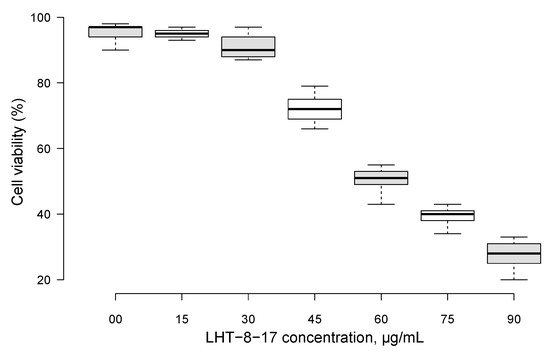

First, LHT-8-17 toxicity against human epidermal cells was studied (Figure 1). Within concentrations that ranged from 0 to 30 mg/mL, cellular metabolic activity was maintained at about the control level. An increase in the LHT-8-17 concentration in the incubating medium from 30 to 90 µg/mL led to progredient depression of cellular metabolic activity in a concentration-dependent manner.

Figure 1. Metabolic activity of skin epidermal cells exposed to different concentrations of cerium-containing N-acethyl-6-aminohexanoic acid compound (LHT-8-17) in MTT assay. Data presented as a percentage of the cell viability in the control, median ± SD.

3. Efficacy of LHT-8-17 in Healing Linear Wounds

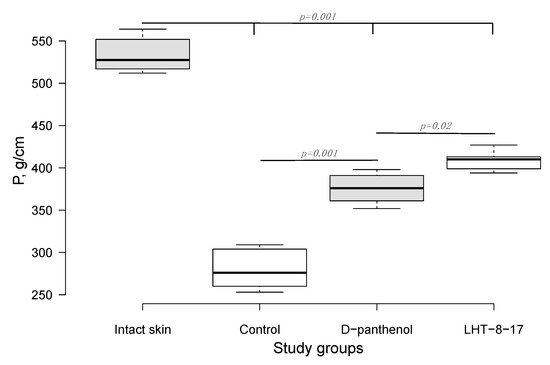

Twenty-one days after the beginning of the experimental treatment of diabetic rat’s skin linear wound, we assessed the efficacy of the cerium-containing formulation. The firmness of each scar was evaluated by registering the power for avulsion of the tissue conjunction formed within the treatment period. As presented in Figure 2, the median power needed to rupture the scar in the control was 283 g/cm; the index value for D-panthenol was 374 g/cm (p = 0.001 compared with the control), while in the LHT-8-17 group, it was 415 g/cm (p = 0.001 compared with the control and p = 0.02 compared with D-panthenol). All scar-related indexes in the study groups were inferior to the value of the power that ruptured intact skin (p = 0.001).

Figure 2. Quantitative evaluation of the skin linear scar firmness in diabetic rats (n = 6 in each group). P (g/cm)—the power needed to rupture the formed scar, presented as the median ± SD. Significant differences were assessed by ANOVA and Tukey tests.

4. Efficacy of LHT-8-17 in Healing Non-Infected Planar Wounds

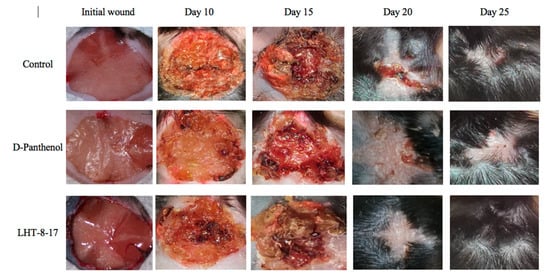

We then assessed the healing efficacy of LHT-8-17 based on the model of the experimental non-infected planar wound in T1D and T2D mice. Figure 3 and Table 1 show a dynamic wound area decrease in the study groups. The duration regarding the wound area with a full reduction in control mice with T1D averaged at 23.7 ± 1.3 days, whereas in mice treated with D-panthenol spray and LHT-8-17 spray, it ranged from 17.8 ± 1.1 to 16.3 ± 0.7 days, respectively (p < 0.05 in comparison with the control). We also observed the largest scar area, which was calipered on the day of complete wound closure in the control rather than in the treatment groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 3. Healing of non-infected planar wounds treated with PBS (control), D-panthenol, and LHT-8-17 for db/db mice treated with T2D.

Table 1. The dynamics of non-infected wound areas (% of initial area’s square) in streptozotocin-induced (T1D) and db/db (T2D) mice, topically treated with 4 mg LHT-8-17 and 4 mg D-panthenol as a spray twice daily, mean ± SD.

| Study Group | Wound Area, % of Initial Area’s Square | Average Time of Full Wound Healing, Days | Scar Area *, mm2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Wound | Day 10 | Day 15 | Day 20 | Day 25 | Day 30 | |||

| C57Bl6 mice with T1D | ||||||||

| Control | n = 20 100 ± 0 |

n = 15 55 ± 2 |

n = 10 32 ± 3 |

n = 5 9 ± 4 |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

23.7 ± 1.3 | 56 ± 4 |

| D-Panthenol | n = 20 100 ± 0 |

n = 15 25 ± 3 † |

n = 10 6 ± 4 † |

n = 5 0 ± 0 † |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

17.8 ± 1.1 † | 39 ± 3 † |

| LHT-8-17 | n = 20 100 ± 0 |

n = 15 21 ± 4 † |

n = 10 5 ± 3 † |

n = 5 0 ± 0 † |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

16.3 ± 0.7 † | 39 ± 4 † |

| db/db mice with T2D | ||||||||

| Control | n = 20 100 ± 0 |

n = 15 70 ± 4 |

n = 10 42 ± 5 |

n = 5 13 ± 4 |

n = 5 7 ± 3 |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

28.5 ± 1.5 | 74 ± 4 |

| D-Panthenol | n = 20 100 ± 0 |

n = 15 76 ± 3 |

n = 10 35 ± 4 |

n = 5 16 ± 3 |

n = 5 5 ± 3 |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

27.7 ± 1.1 | 56 ± 3 † |

| LHT-8-17 | n = 20 100 ± 0 |

n = 15 33 ± 4 †,‡ |

n = 10 21 ± 3 †,‡ |

n = 5 5 ± 2 †,‡ |

n = 5 0 ± 0 †,‡ |

n = 5 0 ± 0 |

22.3 ± 1.0 †,‡ | 43 ± 4 †,‡ |

Note: † p < 0.05 compared with the control group, ‡ p < 0.05 compared with D-panthenol (ANOVA and Tukey criterion); * scar area was calipered on the day of complete wound closure.

Full self-covering of planar skin defect in control mice with T2D was completed in 28.5 ± 1.5 days and left a 74 ± 4 mm2 scar. Both values surpassed similar ones in the case of the T1D control. Local application of 4 mg D-panthenol twice daily for 20 days did not accelerate the wound covering, but resulted in a reduction of the scar area from 74 ± 4 mm2 to 56 ± 3 mm2 (p = 0.005). In contrast, spraying of LHT-8-17 at an equal dose accelerated wound healing to 22.3 ± 1.0 days (p = 0.01 in comparison with both the control and D-panthenol) and decreased the scar area.

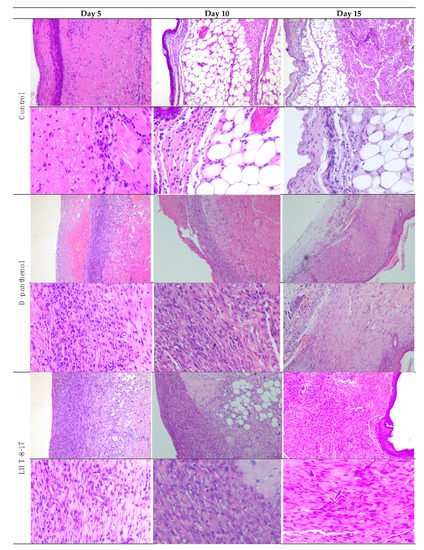

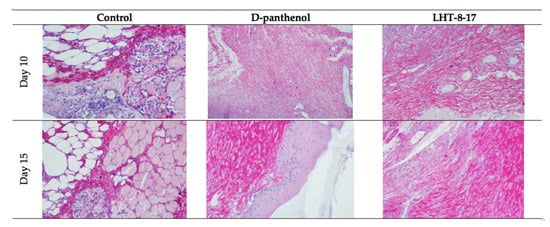

Comparative and dynamic evaluation of wound histology showed sufficient differences among study groups dependent on the diabetic model (Figure 4). Thus, wound healing in the control with acute streptozotocin-induced DM was morphologically presented as an inflammation in the non-infected skin defect with edema, lymphoid, and histiocyte tissue infiltration on days 5–10 with the formation of coarse connective tissue scar by day 25 as an outcome. Van Geison’s staining revealed massive collagen expansion as a focus of aseptic inflammation from day 10 of the pathology onset (Figure 5). Both treatment options allowed the prevention of the inflammatory transformation of the process; instead, we observed primary epithelization of the skin defect by day 15 with low intensity of collagen production. In a study with chronic T2D, wound histology of control animals evolved the same way as that in the case of T1D but more slowly (Figure 2, Table 1). Topical application of LHT-8-17 induced leukocyte prevalence in the inflammatory focus with more rapid clearance of necrotic debris from the wound. A high intensity of collagen production was observed from day 10. The forming scar was more fragile in comparison with both the control and reference pharmacological agent.

Figure 4. Micromorphology of repairing diabetic wound treated with LHT-8-17, db/db mice: hematoxylin and eosin, first line in each section—100×, second line in each section—400× (n = 5 in each subgroup). In control: on day 5, the wound bottom is covered by thick dense fibrin with many neutrophils in deep layers (black arrow) while the underlying layer has proliferating fibroblasts (red arrow); on day 10, the wound base is covered by immature granulation tissue, with a superficial thin layer of loose fibrin highly infiltrated by neutrophils (black arrow); underlying deep layers are infiltrated by macrophages, mast cells, lymphocytes, and fibroblasts involving subcutaneous fat tissue (red arrow); on day 15, the wound base central part is covered by fibrin threads, and slight epithelialization is developing on the periphery (black arrow); a thin layer of granulation tissue consists of macrophages, lymphocytes, and some neutrophils (red arrow). In the D-panthenol group: on day 5, thick fibrin with leukocytes covers the wound base, and an underlying thick layer of granulation tissue extends to the fascia propria (black arrow); granulation tissue contains macrophages and lymphocytes, parallel oriented oval and spindle shaped fibroblasts, numerous engorged capillaries (red arrow); on day 10, the wound base is covered by fibrin threads with underlying immature granulation tissue characterized by cell infiltrate and numerous engorged capillaries, some of which have a vertical orientation, oval and spindle shaped fibroblasts (black arrow); diffuse neutrophilic and lympho-macrophage infiltration is noted (red arrow); on day 15, the wound epithelization is developed (black arrow), and the underlying dermis contain mature collagen fibers (red arrow). In the LHT-8-17 group: thin fibrin with leukocytes covers the wound base, and an underlying thick layer of granulation tissue extends to subcutaneous fat tissue (black arrow); granulation tissue consists of cell infiltrate (macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils) and numerous engorged vertically oriented capillaries, as well as parallel-oriented oval and spindle shaped fibroblasts (red arrow); on day 10, epithelization is developing on the wound periphery, and mature granulation tissue is characterized by cell infiltrate, numerous vertically oriented engorged capillaries, and parallel oriented spindle shaped fibroblasts (black arrow); diffuse light neutrophilic and lympho-macrophage infiltration is noted (red arrow); on day 15, the wound epithelization is developed (black arrow), and the underlying dermis contains mature collagen fibers (red arrow).

Figure 5. Van Geison’s staining of diabetic wound sections on days 10 and 15 of experimental topical therapy with LHT-8-17, db/db mice, 400× (n = 5 in each subgroup). Arrows point out positively-stained collagen. Thin and chaotically oriented collagen fascicles intrude muscular and fat layers in the control. Topical application of D-panthenol leads to the formation of a compact collagen layer. In the LHT-8–17 group on day 10, big masses of collagen fascicles form a single layer that transforms to a fibrotic condition by day 15.

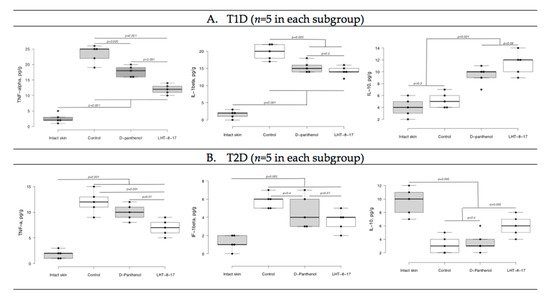

We then assessed whether LHT-8-17 targeted the intensity of wound inflammation in diabetic animals by determining TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 tissue concentrations (Figure 6). Tissue levels of both pro-inflammatory and resolutery cytokines were determined at the same time point due to sufficient extension of the inflammatory phase of wound healing in diabetic mice accompanied by overregulation of pro-inflammatory signaling [6]. In the model of T1D (Figure 6A), by day 5 of the experiment, the TNF-α concentration in wound tissue increased to 25 ± 4 pg/g (p = 0.001 in comparison with intact skin). We measured congruous elevation of the IL-1β tissue level accompanied by depression of the IL-10 concentration (p = 0.001). In the group of LHT-8-17-treated animals, the TNF-α tissue concentration averaged 12 ± 1 pg/g, the IL-1β level did not exceed 15 ± 2 pg/g, while the IL-10 concentration reached 12 ± 2 pg/g.

Figure 6. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 tissue levels on day 5 of wound reparation under topical treatment with LHT-8-17 and the reference medication. Significance of differences was estimated using ANOVA and the Tukey criterion. (A) animals with type 1 of DM; (B) animals with type 2 of DM.

In the control group of animals with type 2 diabetes, both pro-inflammatory cytokine tissue levels were inferior to that of the T1D control group (Figure 6B). While D-panthenol did not address the TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-10 imbalance, LHT-8-17 partly prevented TNF-α and IL-1β elevation (p = 0.001 compared with the control) and IL-10 depression (p = 0.005 compared with the control and D-panthenol).

We then evaluated the oxidative status of wound tissues on days 5 and 10 (Table 2) using Fe-induced chemiluminescence. First, wound tissue oxidative status was assessed in the T1D model. On day 5, the LOSA level in wound tissue increased more than twice compared with intact skin (Table 2) whereas TAC proportionally decreased. By day 10, the LOSA level gradually decreased to 6.7 ± 0.3 imp/s, and TAC increased to 1.7 ± 0.2 imp/s. Total application of D-panthenol impacted oxidative stress intensity at both checking points (p < 0.05 compared with the control), but had no influence on the tissue antioxidant capacity. In contrast, spraying of 4 mg LHT-8-17 twice daily along with tissue LOSA suppression led to significant TAC elevation up to 2.1 ± 0.3 imp/s (p < 0.05 compared with the control) on day 5 and then to 2.7 ± 0.2 imp/s on day 10 (p < 0.05 compared with the control and reference drug).

Table 2. Local oxidative stress activity (LOSA) and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of wound tissue of diabetic mice topically treated with LHT-8-17.

| Study Group | Fe-Induced Chemiluminescence, ×103 imp/s | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 5 | Day 10 | |||

| LOSA | TAC | LOSA | TAC | |

| T1D model (n = 5 in each subgroup) | ||||

| Intact skin | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.3 |

| Control | 8.3 ± 0.4 * | 1.0 ± 0.2 * | 6.7 ± 0.3 * | 1.7 ± 0.2 * |

| D-panthenol | 6.6 ± 0.3 *,# | 1.7 ± 0.4 * | 4.3 ± 0.4 *,# | 1.9 ± 0.3 * |

| LHT-8-17 | 5.2 ± 0.2 *,# | 2.1 ± 0.3 *,# | 4.2 ± 0.3 *,# | 2.7 ± 0.2 #,† |

| T2D model (n = 5 in each subgroup) | ||||

| Intact skin | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.4 |

| Control | 12.7 ± 0.4 * | 0.5 ± 0.1 * | 11.8 ± 0.5 * | 0.7 ± 0.2 * |

| D-panthenol | 9.4 ± 0.3 *,# | 1.3 ± 0.3 *,# | 8.9 ± 0.4 * | 1.5 ± 0.3 # |

| LHT-8-17 | 8.3 ± 0.5 *,# | 1.9 ± 0.2 *,# | 6.3 ± 0.3 *,#,† | 2.2 ± 0.1 #,† |

Note: p < 0.05 * compared with intact skin; # compared with appropriate control; † compared with D-panthenol (ANOVA; Tukey criterion).

The LOSA level in wound tissue of T2D db/db mice averaged 12.7 ± 0.4 imp/s on day 5 of the observation and remained elevated by day 10. It was associated with deep depression of TAC. The reference drug partly prevented LOSA growth on days 5 and 10 (p < 0.05 compared with the control) and induced TAC on both days of the observation. In the LHT-8-17 group, we registered proportional depression of tissue LOSA accompanied by TAC induction. The changes were similar to the D-panthenol group, but more pronounced on day 10 of the experiment.

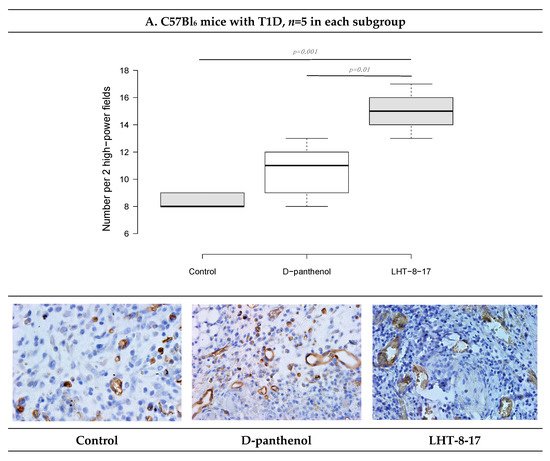

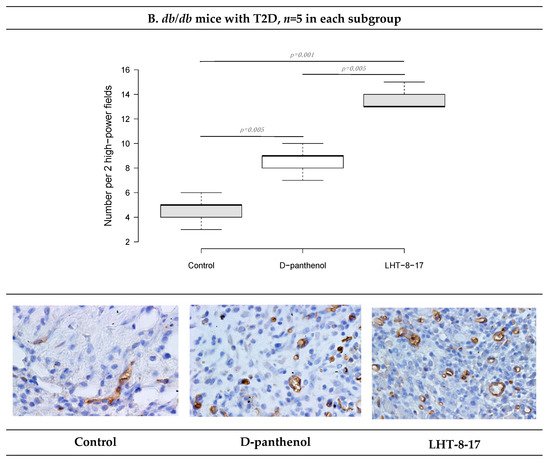

We then assessed the vascular density of the repairing diabetic wound on day 5 of the experiment onset. It was previously demostrated that endothelial cells expressed CD34; hence, to assess whether LHT-8-17 influenced micro-vessels’ intervention into the wound bed, two randomly chosen fields of tissue section stained by anti-CD34 antibody were evaluated (Figure 7). Topical application of LHT-8-17 stimulated vascularization of newly-developing tissues in the wound bed, and number of micro-vessels in the study group was 14.9 ± 0.7 per two high-power fields vs. 8.3 ± 0.3 in the T1D control (p = 0.001). In the model of type 2 diabetes mellitus, the depression of angiogenesis in the control group was even deeper (4.2 ± 0.2), while in the study group, the index averaged at 13.7 ± 0.3 (p = 0.001 compared with the control).

Figure 7. Vascular density and CD34+ expression status in wound tissues of animals with T1D and T2D topically treated with 4 mg LHT-8-17 twice daily, on day 10 of the observation: (A,B)—T1D and T2D models; micro-vessel number per specimen is presented as the median ± SD, significance of differences was estimated using ANOVA and the Tukey criterion; wound tissue sections stained by rabbit monoclonal anti-CD34 antibody, IHC, 400×.

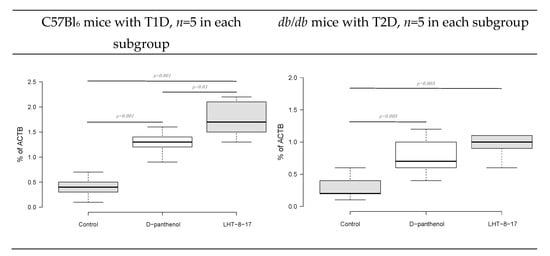

Fibroblast intervention in the wound bottom reflects the velocity of fresh granulation development. The process is regulated by FGF/FGFR signaling [18]. We then assessed the FGFR3 gene transcript expression as a percentage of the ACTB housekeeping gene mRNA concentration. The marker expression was evaluated in fresh granulations that infiltrated the wound bed on day 10 of the experimental therapy with LHT-8-17 (Figure 8). Connective tissue of both types of diabetic wounds was characterized by low FGFR3 gene expression by day 10 of reparation with the greatest depression in wounded db/db mice. Topical treatment with cerium N-acetyl-6-aminohexanoate spray led to significant elevation of the expression up to 1.73 ± 0.4% in the model of T1D (p = 0.001 compared with the control), and to 1.05 ± 0.2% in the T2D model (p = 0.005 compared with the control).

Figure 8. FGFR3 gene transcript expression as a percentage of the ACTB housekeeping gene mRNA concentration in fresh granulations on the day of experimental treatment with LHT-8-17. Data are presented as the median ± SD; significance of differences was estimated using ANOVA and the Tukey criterion.

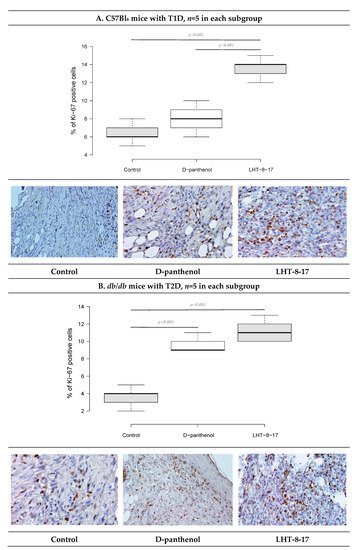

As recently shown, cellular Ki-67 positivity correlated with the proliferative potency of tissues during the regenerative stage of wound healing [19]. The influence of LHT-8-17 on the wound bed cell proliferation was assessed by Ki-67 expression on day 10 of the observation (Figure 9). In the T1D control, only 6.7 ± 0.4% of cells that populated the wound bed displayed Ki-67 positivity. Anti-Ki-67-stained cells were presented largely by fibroblasts, while the keratinocyte population contained single stained cells. Local application of the cerium-containing formulation led to increased Ki-67 cell positivity up to 13.9 ± 0.3% (p = 0.001 compared with the control), with sufficient input of epidermal progenitors. The proliferation status of wound bed cells in the T2D control was registered at 4.1 ± 0.3%. Both LHT-8-17 and the reference drug induced proliferation of keratinocytes to 11.4 ± 0.3% and 9.2 ± 0.2% (p = 0.001 compared with the control) by day 10 of topical treatment.

Figure 9. Cellular Ki-67 expression status in wound tissues of animals with T1D and T2D topically treated with 4 mg cerium-containing formulation twice daily, on day 10 of the observation: (A,B)—T1D and T2D models; quantitative estimation of Ki67 cell positivity presented as the median ± SD; significance of differences was estimated using ANOVA and the Tukey criterion; wound tissue sections stained by rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki-67 antibody, IHC, 400×.

5. Antimicrobial Property of LHT-8-17

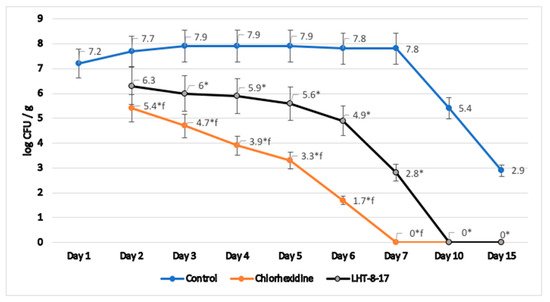

Microbicide action of LHT-8-17 was assessed in homogenates of tissues taken from previously infected and topically treated wounds in type 2 diabetic mice. We analyzed the log of number of S. aureus colonies per g of specific medium during wound reparation (Figure 10). In the control group, wound contamination decreased from 7.2 (log CFU/g) at the outbreak of the experimental pathology to 2.9 by day 15 of observation. Reference topical antiseptic chlorhexidine depressed S. aureus colonization from day 2 of therapy, fully eradicating the wound by day 7 of the observation. LHT-8-17 significantly decreased tissue contamination from day 3 of topical application. Full antimicrobial effect was reached by day 10 of the experimental treatment.

Figure 10. Dynamic S. aureus contamination of experimental diabetic wound tissues, T2D db/db mice; mean ± SD; * p < 0.05 compared with the control, f p < 0.05 compared with chlorhexidine (independent t-test with Bonferroni’s adjustment), n = 3 at each time point.

References

- Clokie, M.; Greenway, A.L.; Harding, K.; Jones, N.J.; Vedhara, K.; Game, F. New horizons in the understanding of the causes and management of diabetic foot disease: Report from the 2017 diabetes UK annual professional conference symposium. Diabet. Med. 2017, 34, 305–315.

- Chan, B.; Cadarette, S.; Wodchis, W.; Wong, J.; Mittmann, N.; Krahn, M. Cost-of-illness studies in chronic ulcers: A systematic review. J. Wound Care 2017, 26, 4–14.

- Olsson, M.; Järbrink, K.; Divakar, U.; Bajpai, R.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 114–125.

- Al-Rubeaan, K.; Al Derwish, M.; Ouizi, S.; Youssef, A.M.; Subhani, S.N.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Alamri, B.N. Diabetic foot complications and their risk factors from a large retrospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124446.

- Maqbool, M.; Dar, M.A.; Gani, I.; Mir, S.A. Animal models in diabetes mellitus: An overview. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2019, 9, 472–475.

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound healing: Cellular mechanisms and pathological outcomes. Open Biol. 2020, 10.

- Velnar, T.; Bailey, T.; Smrkolj, V. The wound healing process: An overview of the cellular and molecular mechanisms. J. Int. Med. Red. 2005, 37, 1528–1542.

- Takeo, M.; Lee, W.; Ito, M. Wound healing and skin regeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a023267.

- Reveles, K.; Duhon, B.; Moore, R.; Hand, E.; Howell, C. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus diabetic foot infections in a large academic hospital: Implications for antimicrobial stewardship. PLoS ONE 2016, 11.

- Jakupec, M.A.; Unfried, P.; Keppler, B.K. Pharmacological properties of cerium compounds. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 153, 101–111.

- Celardo, I.; Pedersen, J.Z.; Traversa, E.; Ghibelli, L. Pharmacological potential of cerium oxide nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1411–1420.

- Gagnon, J.; Fromm, K.M. Toxicity and protective effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles (Nanoceria) depending on their preparation method, particle size, cell type, and exposure route. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 27, 4510–4517.

- Charbgoo, F.; Ahmad, M.B.; Darroudi, M. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Green synthesis and biological applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 1401–1413.

- Kargar, H.; Ghazavi, H.; Darroudi, M. Size-controlled and bio-directed synthesis of ceria nanopowders and their in vitro cytotoxicity effects. Ceramics Int. 2015, 41, 4123–4128.

- Dowding, J.M.; Seal, S.; Self, W.T. Cerium oxide nanoparticles accelerate the decay of peroxynitrite (ONOO−). Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2013, 3, 375–379.

- Bhargava, K.; Arya, A.; Gangwar, A.; Singh, S.K.; Roy, M.; Das, M.; Sethy, N. Cerium oxide nanoparticles promote neurogenesis and abrogate hypoxia-induced memory impairment through AMPK–PKC–CBP signaling cascade. Int. J. Nanomed. 2016, 11, 1159–1173.

- Škvařil, F.; Grünberger, D. Inhibition of spontaneous splitting of γ-globulin preparations with ɛ-aminocaproic acid. Nature 1962, 196, 481–482.

- Nunes, Q.M.; Li, Y.; Sun, C.; Kinnunen, T.K.; Fernig, D.G. Fibroblast growth factors as tissue repair and regeneration therapeutics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1535.

- Butko, Y.; Tkachova, O.; Ulanova, V.; Sahin, Y.; Levashova, O.; Tishakova, T. Immune histochemical study of KI-67 level and ribonucleic acid in the process of healing of burn wounds after treatment with drugs containing dexpanthenol and ceramide. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2019, 9, 4586–4590.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

656

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Jun 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No