| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Victoria Klepsch | + 4336 word(s) | 4336 | 2021-06-01 04:05:41 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 4315 | 2021-06-07 10:40:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

The most successful strategies for solid cancer immunotherapy have centered on targeting the co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory T cell molecules that regulate T cell activation. Although immunotherapy that targets surface receptors such as CTLA-4 and/or PD-1 with recombinant antibodies has been a game changer for cancer treatment, a sizeable subset of patients still fail to respond to, and even fewer patients are cured by, these therapy regimens. The identification of alternate and potentially additive immune checkpoint candidates is intended to improve immunotherapies for a large number of cancer patients. Therefore, we focused on checkpoints located inside immune cells as suitable targets for future cancer drugs. We demonstrated, in recent years, the crucial T lymphocyte-intrinsic role of the orphan nuclear receptor NR2F6 as an intracellular checkpoint in fine-tuning adaptive immunity. NR2F6 induced an anti-inflammatory signal in the T cell compartment.

1. Introduction—T Lymphocytes in Anti-Tumor Immunity

2. Current State of Tumor Immunology

2.1. Cancer Vaccination: A Strategy to Enhance T Lymphocyte-Mediated Anti-Tumor Immunity

2.2. Modulating T Lymphocyte Activation: Checkpoint Inhibitors, Co-Stimulatory Receptors and CAR-T

3. Beyond Current Immune Checkpoint Therapies

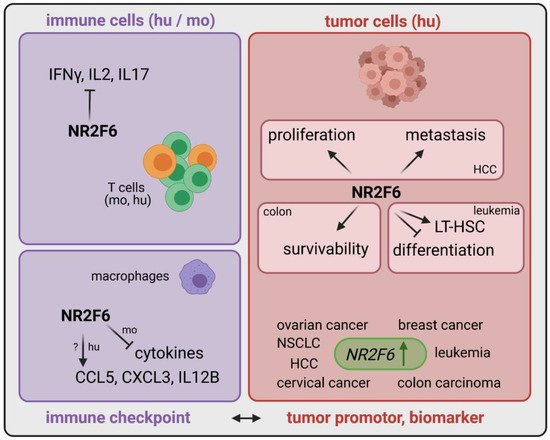

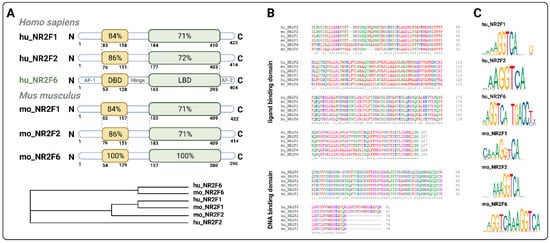

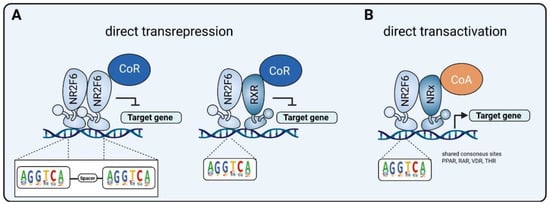

3.1. Intracellular Target NR2F6 in Both Immune Cells and Tumor Cells

| Cancer Type | Expression of NR2F6 | Role of NR2F6 | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukemia | upregulated in patients | elevated population of LT-HSC | [41] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | upregulated in patients | NR2F6 induces proliferation and metastasis via circRHOT1 and TIP60 | [38] |

| Colon carcinoma | upregulated in patients | Nr2f6 increases survivability via XIAP | [39] |

| Cervical cancer | upregulated in patients | correlation between metastasis, poor prognosis and NR2F6 expression | [42] |

| Ovarian cancer | upregulated in patients | DDA1 is induced by NR2F6 and predicts poor outcome | [43][44] |

| Breast cancer | upregulated in patients | n.d. | [45][46] |

| Lung cancer | upregulated in patients | MiR-142-3p inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion via NR2F6 inhibition | [47] |

| Effector T cells (mo and hu) | upregulated upon stimulation | transcriptional repressor directly antagonizing key cytokine gene loci | [40][48][49][50] |

| Macrophages (mo) | n.d. | transcriptional repressor of cytokines | [51] |

| Macrophages (hu) | n.d. | transcriptional activator of chemokines | [51] |

| Tumor cells | upregulated | important for proliferation, metastasis, survivability | [38][39][42][47][52] |

| Neurons (locus coeruleus) | n.d. | control of circadian clock | [53] |

| Hepatocytes (mo and hu) | upregulated | hepatic steatosis promoted by NR2F6 | [54] |

| Kidney | n.d. | NR2F6 as a negative regulator of renin gene transcription | [55] |

3.2. Inducible Immune Checkpoint at the Tumor Site May Boost a Localized Effector T Cell Response with Fewer Systemic Irae

3.3. Double Score Principle of NR2F6 Antagonists

References

- Waldman, A.D.; Fritz, J.M.; Lenardo, M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: From T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 651–668.

- Swann, J.B.; Smyth, M.J. Immune surveillance of tumors. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1137–1146.

- Koebel, C.M.; Vermi, W.; Swann, J.B.; Zerafa, N.; Rodig, S.J.; Old, L.J.; Smyth, M.J.; Schreiber, R.D. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature 2007, 450, 903–907.

- Eyles, J.; Puaux, A.L.; Wang, X.; Toh, B.; Prakash, C.; Hong, M.; Tan, T.G.; Zheng, L.; Ong, L.C.; Jin, Y.; et al. Tumor cells disseminate early, but immunosurveillance limits metastatic outgrowth, in a mouse model of melanoma. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2030–2039.

- Romero, I.; Garrido, C.; Algarra, I.; Collado, A.; Garrido, F.; Garcia-Lora, A.M. T lymphocytes restrain spontaneous metastases in permanent dormancy. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 1958–1968.

- Park, S.L.; Buzzai, A.; Rautela, J.; Hor, J.L.; Hochheiser, K.; Effern, M.; McBain, N.; Wagner, T.; Edwards, J.; McConville, R.; et al. Tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells promote melanoma–immune equilibrium in skin. Nature 2019, 565, 366–371.

- Loi, S.; Drubay, D.; Adams, S.; Pruneri, G.; Francis, P.A.; Lacroix-Triki, M.; Joensuu, H.; Dieci, M.V.; Badve, S.; Demaria, S.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and prognosis: A pooled individual patient analysis of early-stage triple-negative breast cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 559–569.

- Oh, D.Y.; Kwek, S.S.; Raju, S.S.; Li, T.; McCarthy, E.; Chow, E.; Aran, D.; Ilano, A.; Pai, C.C.S.; Rancan, C.; et al. Intratumoral CD4+ T Cells Mediate Anti-tumor Cytotoxicity in Human Bladder Cancer. Cell 2020, 181, 1612–1625.e13.

- Quezada, S.A.; Simpson, T.R.; Peggs, K.S.; Merghoub, T.; Vider, J.; Fan, X.; Blasberg, R.; Yagita, H.; Muranski, P.; Antony, P.A.; et al. Tumor-reactive CD4(+) T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J. Exp. Med. 2010, 207, 637–650.

- Fauskanger, M.; Haabeth, O.A.W.; Skjeldal, F.M.; Bogen, B.; Tveita, A.A. Tumor killing by CD4+ T cells is mediated via induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent macrophage cytotoxicity. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1684.

- Curiel, T.J.; Coukos, G.; Zou, L.; Alvarez, X.; Cheng, P.; Mottram, P.; Evdemon-Hogan, M.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Zhang, L.; Burow, M.; et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 942–949.

- Jordanova, E.S.; Gorter, A.; Ayachi, O.; Prins, F.; Durrant, L.G.; Kenter, G.G.; Van Der Burg, S.H.; Fleuren, G.J. Human leukocyte antigen class I, MHC class I chain-related molecule A, and CD8+/regulatory T cell ratio: Which variable determines survival of cervical cancer patients? Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2028–2035.

- Onda, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Pastan, I. Depletion of regulatory T cells in tumors with an anti-CD25 immunotoxin induces CD8 T cell-mediated systemic antitumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4575–4582.

- Ward, J.P.; Gubin, M.M.; Schreiber, R.D.; States, U. Therapeutically Induced Immune Responses to Cancer. Adv. Immunol. 2016, 130, 25–74.

- Jou, J.; Harrington, K.J.; Zocca, M.B.; Ehrnrooth, E.; Cohen, E.E.W. The changing landscape of therapeutic cancer vaccines-novel platforms and neoantigen identification. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 689–703.

- Ott, P.A.; Hu, Z.; Keskin, D.B.; Shukla, S.A.; Sun, J.; Bozym, D.J.; Zhang, W.; Luoma, A.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Peter, L.; et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature 2017, 547, 217–221.

- Sahin, U.; Derhovanessian, E.; Miller, M.; Kloke, B.P.; Simon, P.; Löwer, M.; Bukur, V.; Tadmor, A.D.; Luxemburger, U.; Schrörs, B.; et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 2017, 547, 222–226.

- Keskin, D.B.; Anandappa, A.J.; Sun, J.; Tirosh, I.; Mathewson, N.D.; Li, S.; Oliveira, G.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Felt, K.; Gjini, E.; et al. Neoantigen vaccine generates intratumoral T cell responses in phase Ib glioblastoma trial. Nature 2019, 565, 234–239.

- Hu, Z.; Leet, D.E.; Allesøe, R.L.; Oliveira, G.; Li, S.; Luoma, A.M.; Liu, J.; Forman, J.; Huang, T.; Iorgulescu, J.B.; et al. Personal neoantigen vaccines induce persistent memory T cell responses and epitope spreading in patients with melanoma. Nat. Med. 2021, 27.

- D’Alise, A.M.; Leoni, G.; Cotugno, G.; Troise, F.; Langone, F.; Fichera, I.; De Lucia, M.; Avalle, L.; Vitale, R.; Leuzzi, A.; et al. Adenoviral vaccine targeting multiple neoantigens as strategy to eradicate large tumors combined with checkpoint blockade. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10.

- Sahin, U.; Oehm, P.; Derhovanessian, E.; Jabulowsky, R.A.; Vormehr, M.; Gold, M.; Maurus, D.; Schwarck-Kokarakis, D.; Kuhn, A.N.; Omokoko, T.; et al. An RNA vaccine drives immunity in checkpoint-inhibitor-treated melanoma. Nature 2020, 585, 107–112.

- Poran, A.; Scherer, J.; Bushway, M.E.; Besada, R.; Balogh, K.N.; Wanamaker, A.; Williams, R.G.; Prabhakara, J.; Ott, P.A.; Hu-Lieskovan, S.; et al. Combined TCR Repertoire Profiles and Blood Cell Phenotypes Predict Melanoma Patient Response to Personalized Neoantigen Therapy plus Anti-PD-1. Cell Rep. Med. 2020, 1, 100141.

- Reinhard, K.; Rengstl, B.; Oehm, P.; Michel, K.; Billmeier, A.; Hayduk, N.; Klein, O.; Kuna, K.; Ouchan, Y.; Wöll, S.; et al. An RNA vaccine drives expansion and efficacy of claudin-CAR-T cells against solid tumors. Science 2020, 367, 446–453.

- Wolchok, J.D.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Rutkowski, P.; Grob, J.-J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Wagstaff, J.; Schadendorf, D.; Ferrucci, P.F.; et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1345–1356.

- Hargadon, K.M.; Johnson, C.E.; Williams, C.J. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 62, 29–39.

- Qin, S.; Xu, L.; Yi, M.; Yu, S.; Wu, K.; Luo, S. Novel immune checkpoint targets: Moving beyond PD-1 and CTLA-4. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 155.

- Choi, Y.; Shi, Y.; Haymaker, C.L.; Naing, A.; Ciliberto, G.; Hajjar, J. T cell agonists in cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2020, 8.

- Larkin, J.; Chiarion-Sileni, V.; Gonzalez, R.; Grob, J.J.; Cowey, C.L.; Lao, C.D.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Smylie, M.; Rutkowski, P.; et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 23–34.

- Wherry, E.J.; Kurachi, M. Molecular and cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 486–499.

- Skokos, D.; Waite, J.C.; Haber, L.; Crawford, A.; Hermann, A.; Ullman, E.; Slim, R.; Godin, S.; Ajithdoss, D.; Ye, X.; et al. A class of costimulatory CD28-bispecific antibodies that enhance the antitumor activity of CD3-bispecific antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12, eaaw7888.

- Mitchison, N. Studies on the immunological response to foreign tumor transplants in the mouse. J. Exp. Med. 1955, 102, 157–177.

- Fefer, A. Immunotherapy and Chemotherapy of Moloney Sarcoma Virus-induced Tumors in Mice. Cancer Res. 1969, 29, 2177–2183.

- Claus, C.; Ferrara, C.; Xu, W.; Sam, J.; Lang, S.; Uhlenbrock, F.; Albrecht, R.; Herter, S.; Schlenker, R.; Hösser, T.; et al. Tumor-Targeted 4-1BB agonists for combination with T cell bispecific antibodies as off-The-shelf therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaav5989.

- You, G.; Lee, Y.; Kang, Y.W.; Park, H.W.; Park, K.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, D.; et al. B7-H3×4-1BB bispecific antibody augments antitumor immunity by enhancing terminally differentiated CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eaax3160.

- Avanzi, M.P.; Brentjens, R.J. Emerging role of CAR-T cells in Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. JNCCN J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2017, 15, 1429–1437.

- Rosenberg, S.A.; Packard, B.S.; Aebersold, P.M.; Solomon, D.; Topalian, S.L.; Toy, S.T.; Simon, P.; Lotze, M.T.; Yang, J.C.; Seipp, C.A.; et al. Use of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Interleukin-2 in the Immunotherapy of Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1676–1680.

- Feins, S.; Kong, W.; Williams, E.F.; Milone, M.C.; Fraietta, J.A. An introduction to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, S3–S9.

- Wang, L.; Long, H.; Zheng, Q.; Bo, X.; Xiao, X.; Li, B. Circular RNA circRHOT1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by initiation of NR2F6 expression. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18.

- Li, X.; Jiao, S.; Sun, H.; Xue, J.; Zhao, W.; Fan, L.; Wu, G.; Fang, J. The orphan nuclear receptor EAR2 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer and it regulates survivability of colon cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2011, 309, 137–144.

- Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Gruber, T.; Lutz-Nicoladoni, C.; Thuille, N.; Fresser, F.; Labi, V.; Schiefermeier, N.; Warnecke, M.; Huber, L.; Villunger, A.; et al. The Nuclear Orphan Receptor NR2F6 Suppresses Lymphocyte Activation and T Helper 17-Dependent Autoimmunity. Immunity 2008, 29, 205–216.

- Ichim, C.V.; Atkins, H.L.; Iscove, N.N.; Wells, R.A. Identification of a role for the nuclear receptor EAR-2 in the maintenance of clonogenic status within the leukemia cell hierarchy. Leuk. Off. J. Leuk. Soc. Am. Leuk. Res. Fund. UK 2011, 25, 1687–1696.

- Niu, C.; Sun, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Xu, L.; Li, J.; Xu, B.; Zhang, Y. NR2F6 expression correlates with pelvic lymph node metastasis and poor prognosis in early-stage cervical cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1694.

- Liu, J.; Li, T.; Liu, X.L. DDA1 is induced by NR2F6 in ovarian cancer and predicts poor survival outcome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 1206–1213.

- Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Niu, C.; Lin, C.; Wu, X.; Jian, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, L.; Dai, Y.; Ouyang, Y.; et al. Nuclear orphan receptor NR2F6 confers cisplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells by activating the Notch3 signaling pathway. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 1921–1934.

- Muscat, G.E.O.; Eriksson, N.A.; Byth, K.; Loi, S.; Graham, D.; Jindal, S.; Davis, M.J.; Clyne, C.; Funder, J.W.; Simpson, E.R.; et al. Research resource: Nuclear receptors as transcriptome: Discriminant and prognostic value in breast cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 350–365.

- Antoniou, A.C.; Wang, X.; Fredericksen, Z.S.; McGuffog, L.; Tarrell, R.; Sinilnikova, O.M.; Healey, S.; Morrison, J.; Kartsonaki, C.; Lesnick, T.; et al. A locus on 19p13 modifies risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 mutation carriers and is associated with hormone receptor-negative breast cancer in the general population. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 885–892.

- Jin, C.; Xiao, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, G.; Ren, S. MiR-142-3p suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion through inhibition of NR2F6 in lung adenocarcinoma. Hum. Cell 2019, 32, 437–446.

- Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Meisel, M.; Fresser, F.; Thuille, N.; Müller, M.; Roth, L.; Katopodis, A.; Baier, G. Nuclear orphan receptor NR2F6 directly antagonizes NFAT and RORγt binding to the Il17a promoter. J. Autoimmun. 2012, 39, 428–440.

- Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Klepsch, V.; Wallner, S.; Siegmund, K.; Klepsch, S.; Tuzlak, S.; Villunger, A.; Kaminski, S.; Pfeifhofer-Obermair, C.; Gruber, T.; et al. The Nuclear Orphan Receptor NR2F6 Is a Central Checkpoint for Cancer Immune Surveillance. Cell Rep. 2015, 12, 2072–2085.

- Klepsch, V.; Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Do-Dinh, P.; Jakic, B.; Offermann, A.; Efremova, M.; Sopper, S.; Rieder, D.; Krogsdam, A.; Gamerith, G.; et al. Nuclear receptor NR2F6 inhibition potentiates responses to PD-L1/PD-1 cancer immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1538.

- Santoso, C.S.; Li, Z.; Lal, S.; Yuan, S.; Gan, K.A.; Agosto, L.M.; Liu, X.; Carrasco, P.S.; Sewell, J.A.; Henderson, A.; et al. Comprehensive mapping of the human cytokine gene regulatory network. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 12055–12073.

- Ichim, C.V.; Dervovic, D.D.; Chan, L.S.A.; Robertson, C.J.; Chesney, A.; Reis, M.D.; Wells, R.A. The orphan nuclear receptor EAR-2 (NR2F6) inhibits hematopoietic cell differentiation and induces myeloid dysplasia in vivo. Biomark. Res. 2018, 6.

- Warnecke, M.; Oster, H.; Revelli, J.; Alvarez-bolado, G.; Eichele, G. Abnormal development of the locus impairs the functionality of the forebrain clock and affects nociception. Genes Dev. 2005, 2, 614–625.

- Zhou, B.; Jia, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xiang, L.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, P.; Liu, B.; Ren, X.; Bian, H.; Xie, L.; et al. The Nuclear Orphan Receptor NR2F6 Promotes Hepatic Steatosis through Upregulation of Fatty Acid Transporter CD36. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7.

- Liu, X.; Huang, X.; Sigmund, C.D. Identification of a nuclear orphan receptor (Ear2) as a negative regulator of renin gene transcription. Circ. Res. 2003, 92, 1033–1040.

- Eckerle, S.; Brune, V.; Döring, C.; Tiacci, E.; Bohle, V.; Sundström, C.; Kodet, R.; Paulli, M.; Falini, B.; Klapper, W.; et al. Gene expression profiling of isolated tumour cells from anaplastic large cell lymphomas: Insights into its cellular origin, pathogenesis and relation to Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk. Off. J. Leuk. Soc. Am. Leuk. Res. Fund. UK 2009, 23, 2129–2138.

- Gu-Trantien, C.; Loi, S.; Garaud, S.; Equeter, C.; Libin, M.; De Wind, A.; Ravoet, M.; Buanec, H.L.; Sibille, C.; Manfouo-Foutsop, G.; et al. CD4+ follicular helper T cell infiltration predicts breast cancer survival. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2873–2892.

- Bassi, C.; Li, Y.T.; Khu, K.; Mateo, F.; Baniasadi, P.S.; Elia, A.; Mason, J.; Stambolic, V.; Pujana, M.A.; Mak, T.W.; et al. The acetyltransferase Tip60 contributes to mammary tumorigenesis by modulating DNA repair. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1198–1208.

- Cregan, S.; McDonagh, L.; Gao, Y.; Barr, M.P.; O’Byrne, K.J.; Finn, S.P.; Cuffe, S.; Gray, S.G. KAT5 (Tip60) is a potential therapeutic target in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 1290–1296.

- Shiota, M.; Yokomizo, A.; Masubuchi, D.; Tada, Y.; Inokuchi, J.; Eto, M.; Uchiumi, T.; Fujimoto, N.; Naito, S. Tip60 promotes prostate cancer cell proliferation by translocation of androgen receptor into the nucleus. Prostate 2010, 70, 540–554.

- Yoest, J. Clinical features, predictive correlates, and pathophysiology of immune-related adverse events in immune checkpoint inhibitor treatments in cancer: A short review. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2017, 6, 73–82.

- Das, S.; Johnson, D.B. Immune-related adverse events and anti-tumor efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 306.

- Jamal, S.; Hudson, M.; Fifi-Mah, A.; Ye, C. Immune-related adverse events associated with cancer immunotherapy: A review for the practicing rheumatologist. J. Rheumatol. 2020, 47, 166–175.

- Adam, K.; Iuga, A.; Tocheva, A.S.; Mor, A. A novel mouse model for checkpoint inhibitor-induced adverse events. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–14.

- Wang, L.; Cheng, C.M.; Qin, J.; Xu, M.; Kao, C.Y.; Shi, J.; You, E.; Gong, W.; Rosa, L.P.; Chase, P.; et al. Small-molecule inhibitor targeting orphan nuclear receptor COUP-TFII for prostate cancer treatment. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz8031.

- Khalil, B.D.; Sanchez, R.; Rahman, T.; Rodriguez-Tirado, C.; Moritsch, S.; Martinez, A.R.; Miles, B.; Farias, E.; Mezei, M.; Cheung, J.F.; et al. A specific agonist of the orphan nuclear receptor NR2F1 suppresses metastasis through the induction of cancer cell dormancy. bioRxiv 2021.

- Rhen, T.; Cidlowski, J.A. Antiinflammatory Action of Glucocorticoids—New Mechanisms for Old Drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 1711–1723.

- Tang, K.; Tsai, S.Y.; Tsai, M.J. COUP-TFs and eye development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2015, 1849, 201–209.

- Klepsch, V.; Pommermayr, M.; Humer, D.; Brigo, N.; Hermann-Kleiter, N.; Baier, G. Targeting the orphan nuclear receptor NR2F6 in T cells primes tumors for immune checkpoint therapy. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 8.