Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yoshinori Matsuo | + 1287 word(s) | 1287 | 2021-05-22 06:50:45 | | | |

| 2 | Lily Guo | Meta information modification | 1287 | 2021-05-27 07:17:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Matsuo, Y. Histone Genes in Drosophila. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10154 (accessed on 12 March 2026).

Matsuo Y. Histone Genes in Drosophila. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10154. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Matsuo, Yoshinori. "Histone Genes in Drosophila" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10154 (accessed March 12, 2026).

Matsuo, Y. (2021, May 27). Histone Genes in Drosophila. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10154

Matsuo, Yoshinori. "Histone Genes in Drosophila." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 May, 2021.

Copy Citation

The evolution of the GC (guanine cytosine) content at the third codon position of the histone genes (H1, H2A, H2B, H3, H4, H2AvD, H3.3A, H3.3B, and H4r) in 12 or more Drosophila species is reviewed. For explaining the evolution of the GC content at the third codon position of the genes, a model assuming selection with a deleterious effect for adenine/thymine and a size effect is presented. The applicability of the model to whole-genome genes is also discussed.

histone gene

1. Introduction

Histones are basic proteins that package and arrange DNA into nucleosomes [1][2][3][4]. There are two major types of histones: a replication-dependent (canonical) type and a replication-independent (replacement) type [5]. In addition to these, centromeric proteins [6][7][8] and histone-like proteins [9] also exist.

In Drosophila, five replication-dependent (canonical) histones are known [10][11]: H2A, H2B, H3, and H4, which are core histones that organize the nucleosome core by forming an octamer comprising two copies of each protein, and H1, which is a linker protein that binds to each nucleosome core [1][2][3][4]. As for replication-independent (replacement) histones, four kinds are currently known in Drosophila: H2AvD, H3.3A, H3.3B, and H4r [12][13][14][15]. In addition to histone modification [16][17][18][19][20][21][22], the replacement of histones by a different histone type causes chromatin remodeling [23][24][25]. Nucleosome remodeling is involved in many important biological processes, such as cell division, differentiation, gene expression, and replication [26][27][28]. Therefore, histone modification and replacement are mechanisms that can lead to epigenetic changes [21][29][30]. In Drosophila, the histone genes for the canonical type of histones are clustered in a repetitive unit, and in Drosophila melanogaster, the unit repeats about 110 times [10][31]. In contrast, the histone genes for the replacement type of histones are found as single genes or with only a few copies per genome, and they contain a few introns [12][13][14][15]. For the detailed structure of the histone genes in Drosophila, please refer to another review article [32]. The mode of molecular evolution of a multigene family, compared to a single gene, can be studied by analyzing histone genes [33].

The usage of codons in protein-coding genes is not uniform among synonymous codons and is biased in many species [34][35]. The mechanism of codon bias has been discussed for decades, and candidate factors include mutation bias, natural selection, and genetic drift [36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]. Unequal usage of codons occurs when the rate of mutations due to nucleotide substitutions is biased or when selection pressure is exerted differently between synonymous codons. Fitness differences among synonymous codons may be present due to differences in the efficiency or speed of translation [45][46]. However, the selection pressure on codons, if any, would be comparatively weaker than that on amino acid sequences; therefore, the codon usage can be influenced by population size [32][39][47][48][49][50][51][52][53]. Since the largest difference in codon usage is observed in the nucleotide at the third codon position of genes, the guanine–cytosine (GC) content at the third codon position is strongly related to codon usage bias. In Drosophila, the higher the GC content at the third codon position is, the stronger the bias of codons [37][40][54]. Moreover, regarding the relationship with the evolutionary rate, the stronger the bias of codons is, the slower the evolutionary rate [55].

In Drosophila saltans, the low GC content of the Xdh and Adh genes was explained by fluctuating mutation bias [56][57]. However, it may also be explained by changes in selection [32][38][50][51][52][53]. Although many Drosophila species have been analyzed for their histone genes [31][49][58][59][60], no changes in the rate of mutations were observed among the species in our analysis [49]. Here, the evolution of the GC content at the third codon position of histone genes in Drosophila is reviewed, and a model that can best explain the evolution of the GC content at the third codon position in Drosophila is presented.

2. Evolution of the GC Content at the Third Codon Position of the Histone Genes in Drosophila

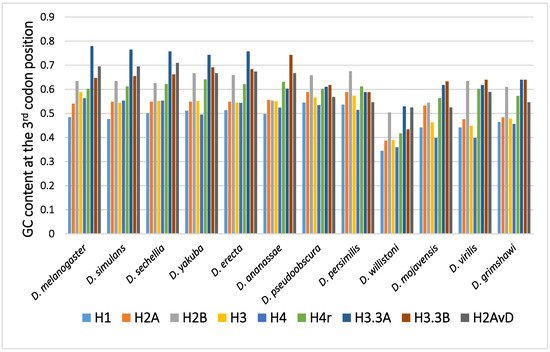

The GC content at the third codon position of the histone genes in 12 Drosophila species is shown in Figure 1. Parts of histone genes data have been published from our laboratory [31][49][51][52][58][59][60]. The rest is obtained from FlyBase (http://flybase.org, accessed on 2017–2019) [61]. Several characteristic points on the evolution of the GC content at the third codon position of histone genes in Drosophila are summarized below.

Figure 1. The GC content at the third codon position of the histone genes in Drosophila. The data grouped according to the Drosophila species.

2.1. Disparity in the GC Content at the Third Codon Position among the Genes

In many Drosophila species, the codon usage of the genes was uneven and varied from gene to gene [36][40][50]. Therefore, the GC content at the third codon position differed between the genes. Although the reason remains unclear, codon bias was found to be related to the level of gene expression, which also varied from gene to gene. The positive relationship found between codon bias and the level of gene expression most likely resulted from the difference in translation efficiency [45][46]. Among the canonical histone genes, H2B showed the highest GC content at the third codon position, while H1 showed the lowest GC content at the third codon position [62]. H1, a linker protein, is expressed at approximately half of the level of the other four canonical histones. This is likely the reason why the GC content at the third codon position of H1 is not as high as those of the core histone genes.

2.2. Disparity in the GC Content at the Third Codon Position between the Genes of the Canonical and Replacement Types of Histones

A comparison of the average GC content at the third codon position of genes in 12 common species revealed a higher GC content at the third codon position in the genes of the replacement type of histones than in those of the canonical type of histones [62][63][64][65]. Analysis of codon bias in the histone genes demonstrated that the difference was caused not by an obvious codon bias in a specific amino acid but by a general tendency that was observed for many codons [62]. Differences in functional differentiation or translation efficiency may be the cause of the differences in GC content at the third codon position between the histone types.

2.3. Disparity in GC Content at the Third Codon Position of the Genes among the Different Species

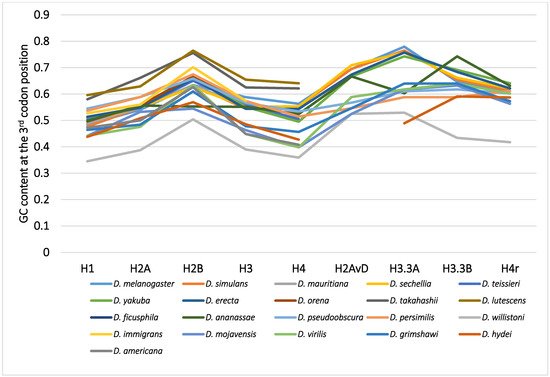

Although variability in the GC content among the genes within a species has been previously noted [36][40][50][51], variability has also been observed between different species [40][51][62]. For example, among 12 Drosophila species, the GC content at the third codon position of many genes in Drosophila willistoni was relatively lower than in the other 11 species [39][62]. Furthermore, when the GC content at the third codon position of corresponding genes was compared between the Drosophila species, nearly parallel differences, similar patterns of ups and downs, were observed for most comparisons (Figure 2). A lower GC content at the third codon position was also observed in the genes of Drosophila species other than these 12 species, such as in Drosophila hydei and Drosophila americana (Figure 1).

Figure 2. The GC content at the third codon position of the nine histone genes in Drosophila. The points from the same species were connected by lines to show the trend for each species.

2.4. Mode of the Evolution of GC Content at the Third Codon Position According to Phylogeny

The differences in GC content at the third codon position according to the Drosophila phylogeny were unexpected and lacked consistency with evolution [33][62]. The GC contents at the third codon position of closely related species showed similar values, but those in distantly related species did not always show larger differences. Unlike the case for nucleotide and amino acid substitutions, the relationship between differences in GC content at the third codon position and the evolutionary distances between species is not co-linear. The differences in GC content at the third codon position are independent of phylogenetic distance.

References

- Kornberg, R.D. Chromatin Structure: A Repeating Unit of Histones and DNA. Science 1974, 184, 868–871.

- Kornberg, R.D. Structure of Chromatin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1977, 46, 931–954.

- McGhee, J.D.; Rau, D.C.; Charney, E.; Felsenfeld, G. Orientation of the nucleosome within the higher order structure of chromatin. Cell 1980, 22, 87–96.

- Cutter, A.R.; Hayes, J.J. A brief review of nucleosome structure. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2914–2922.

- Schümperli, D. Cell-cycle regulation of histone gene expression. Cell 1986, 45, 471–472.

- Malik, H.S.; Henikoff, S. Adaptive evolution of Cid, a centromere-specific histone in Drosophila. Genetics 2001, 157, 1293–1298.

- Vermaak, D.; Hayden, H.S.; Henikoff, S. Centromere targeting element within the histone fold domain of Cid. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 7553–7561.

- Dalal, Y.; Furuyama, T.; Vermaak, D.; Henikoff, S. Structure, dynamics, and evolution of centromeric nucleosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15974–15981.

- Palmer, D.; Snyder, L.A.; Blumenfeld, M. Drosophila nucleosomes contain an unusual histone-like protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 2671–2675.

- Lifton, R.P.; Goldberg, M.L.; Karp, R.W.; Hogness, D.S. The Organization of the Histone Genes in Drosophila melanogaster: Functional and Evolutionary Implications. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1978, 42, 1047–1051.

- Pardue, M.L.; Kedes, L.H.; Weinberg, E.S.; Birnstiel, M.L. Localization of sequences coding for histone messenger RNA in the chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma 1977, 63, 135–151.

- Fretzin, S.; Allan, B.D.; van Daal, A.; Elgin, S.C.R. A Drosophila melanogaster H3.3 cDNA encodes a histone variant identical with the vertebrate H3.3. Gene 1991, 107, 341–342.

- Van Daal, A.; White, E.M.; Gorovsky, M.A.; Elgin, C.R. Drosophila has a single copy of the gene encoding a highly conserved histone H2A variant of the H2A. F/Z type. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988, 16, 7487–7497.

- Akhmanova, A.S.; Bindels, P.C.T.; Xu, J.; Miedema, K.; Kremer, H.; Hennig, W.; Xu, J.; Hennig, W. Structure and expression of histone H3.3 genes in Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila hydei. Genome 1995, 38, 586–600.

- Akhmanova, A.; Miedema, K.; Hennig, W. Identification and characterization of the Drosophila histone H4 replacement gene. FEBS Lett. 1996, 388, 219–222.

- Lawrence, M.; Daujat, S.; Schneider, R. Lateral Thinking: How Histone Modifications Regulate Gene Expression. Trends Genet. 2016, 32, 42–56.

- Jenuwein, T.; Allis, C.D. Translating the Histone Code. Science 2001, 293, 1074–1080.

- Musselman, C.A.; Lalonde, M.-E.; Côté, J.; Kutateladze, T.G. Perceiving the epigenetic landscape through histone readers. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 1218–1227.

- Bannister, A.; Kouzarides, T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 381–395.

- Benson, L.J.; Gu, Y.; Yakovleva, T.; Tong, K.; Barrows, C.; Strack, C.L.; Cook, R.G.; Mizzen, C.A.; Annunziato, A.T. Modifications of H3 and H4 during chromatin replication, nucleosome assembly, and histone exchange. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 9287–9296.

- Zentner, G.E.; Henikoff, S. Regulation of nucleosome dynamics by histone modifications. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 259–266.

- Cedar, H.; Bergman, Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: Patterns and paradigms. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 295–304.

- Santoro, S.W.; Dulac, C. Histone variants and cellular plasticity. Trends Genet. 2015, 31, 516–527.

- Biterge, B.; Schneider, R. Histone variants: Key players of chromatin. Cell Tissue Res. 2014, 356, 457–466.

- Maze, I.; Noh, K.-M.; Soshnev, A.A.; Allis, C.D. Every amino acid matters: Essential contributions of histone variants to mammalian development and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 259–271.

- Becker, P.B.; Workman, J.L. Nucleosome remodeling and epigenetics. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a017905.

- Venkatesh, S.; Workman, J.L. Histone exchange, chromatin structure and the regulation of transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 178–189.

- Grunstein, M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature 1997, 389, 349–352.

- Gaume, X.; Torres-Padilla, M.-E. Regulation of reprogramming and cellular plasticity through histone exchange and histone variant incorporation. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2015, 80, 165–175.

- Henikoff, S. Epigenetic profiling of histone variants. Epigenomics 2009, 101–118.

- Matsuo, Y.; Yamazaki, T. tRNA derived insertion element in histone gene repeating unit of Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989, 17, 225–238.

- Matsuo, Y. Genomic structure and evolution of the histone gene family in Drosophila. Curr. Top. Genet. 2006, 2, 1–14.

- Matsuo, Y.; Yamazaki, T. Nucleotide variation and divergence in the histone multigene family in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 1989, 122, 87–97.

- Wells, D.; Bains, W.; Kedes, L. Codon usage in histone gene families of higher eukaryotes reflects functional rather than phylogenetic relationships. J. Mol. Evol. 1986, 23, 224–241.

- Ikemura, T. Codon Usage and tRNA Content in Unicellular and Multicellular Organisms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1985, 2, 13–34.

- Shields, D.C.; Sharp, P.M.; Higgins, D.G.; Wright, F. “Silent” sites in Drosophila genes are not neutral: Evidence of selection among synonymous codons. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1988, 5, 704–716.

- Poh, Y.-P.; Ting, C.-T.; Fu, H.-W.; Langley, C.H.; Begun, D.J. Population Genomic Analysis of Base Composition Evolution in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biol. Evol. 2012, 4, 1245–1255.

- Lawrie, D.S.; Messer, P.W.; Hershberg, R.; Petrov, D.A. Strong Purifying Selection at Synonymous Sites in D. melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003527.

- Vicario, S.; Moriyama, E.N.; Powell, J.R. Codon usage in twelve species of Drosophila. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 226.

- Moriyama, E.N.; Hartl, D.L. Codon usage bias and base composition of nuclear genes in Drosophila. Genetics 1993, 134, 847–858.

- Powell, J.R.; Moriyama, E.N. Evolution of codon usage bias in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 7784–7790.

- Akashi, H. Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at ‘silent’ sites in Drosophila DNA. Genetics 1995, 139, 1067–1076.

- Li, W.H. Models of nearly neutral mutations with particular implications for nonrandom usage of synonymous codons. J. Mol. Evol. 1987, 24, 337–345.

- Kliman, R.M.; Hey, J. The effects of mutation and natural selection on codon bias in the genes of drosophila. Genetics 1994, 137, 1049–1056.

- Akashi, H. Translational selection and yeast proteome evolution. Genetics 2003, 164, 1291–1303.

- Hartl, D.L.; Moriyama, E.N.; Sawyer, S.A. Selection intensity for codon bias. Genetics 1994, 138, 227–234.

- Ohta, T. Population size and rate of evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 1972, 1, 305–314.

- Ohta, T. The Nearly Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2003, 23, 263–286.

- Matsuo, Y. Molecular evolution of the histone 3 multigene family in the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2000, 16, 339–343.

- Matsuo, Y. Evolutionary change of codon usage for the histone gene family in Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila hydei. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2000, 15, 283–291.

- Matsuo, Y. Evolution of the GC content of the histone 3 gene in seven Drosophila species. Genes Genet. Syst. 2003, 78, 309–318.

- Nakashima, Y.; Higashiyama, A.; Ushimaru, A.; Nagoda, N.; Matsuo, Y. Evolution of GC content in the histone gene repeatingunits from Drosophila lutescens, D. takahashii and D. pseudoobscura. Genes Genet. Syst. 2016, 91, 27–36.

- Lanfear, R.; Kokko, H.; Eyre-Walker, A. Population size and the rate of evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 33–41.

- Bernardi, G.; Bernardi, G. Compositional constraints and genome evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 1986, 24, 1–11.

- Fitch, D.H.; Strausbaugh, L.D. Low codon bias and high rates of synonymous substitution in Drosophila hydei and D. melanogaster histone genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993, 10, 397–413.

- Rodríguez-Trelles, F.; Tarrío, R.; Ayala, F.J. Switch in codon bias and increased rates of amino acid substitution in the Drosophila saltans species group. Genetics 1999, 153, 339–350.

- Rodríguez-Trelles, F.; Tarrío, R.; Ayala, F.J. Fluctuating mutation bias and the evolution of base composition in Drosophila. J. Mol. Evol. 2000, 50, 1–10.

- Tsunemoto, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Tsunemotoa, K.; Matsuo, Y.; Tsunemoto, K.; Matsuo, Y. Molecular evolutionary analysis of a histone gene repeating unit from Drosophila simulans. Genes Genet. Syst. 2001, 76, 355–361.

- Nagoda, N.; Fukuda, A.; Nakashima, Y.; Matsuo, Y. Molecular characterization and evolution of the repeating units of histone genes in Drosophila americana: Coexistence of quartet and quintet units in a genome. Insect Mol. Biol. 2005, 14, 713–717.

- Kakita, M.; Shimizu, T.; Emoto, M.; Nagai, M.; Takeguchi, M.; Hosono, Y.; Kume, N.; Ozawa, T.; Ueda, M.; Bhuiyan, M.S.I.; et al. Divergence and heterogeneity of the histone gene repeating units in the Drosophila melanogaster species subgroup. Genes Genet. Syst. 2003, 78, 383–389.

- Drosophila 12 Genomes Consortium. Evolution of genes and genomes on the Drosophila phylogeny. Nature 2007, 450, 203–218.

- Matsuo, Y. Epigenetics and Codon Usage of the Histone Genes in 12 Drosophila Species. J. Phylogenet. Evol. Biol. 2017, 5, 1–7.

- Matsuo, Y.; Kakubayashi, N. Epigenetics Evolution and Replacement Histones: Evolutionary Changes at Drosophila H3.3A and H3.3B. J. Phylogenet. Evol. Biol. 2016, 4, 1–8.

- Yamamoto, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Nakamura, M.; Kakubayashi, N.; Saito, Y.; Matsuo, Y. Epigenetics Evolution and Replacement Histones: Evolutionary Changes at Drosophila H4r. J. Phylogenet. Evol. Biol. 2016, 4, 3.

- Matsuo, Y.; Kakubayashi, N. Epigenetics Evolution and Replacement Histones: Evolutionary Changes at Drosophila H2AvD. J. Data Min. Genom. Proteom. 2017, 8, 1.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

936

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 May 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No