| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lei Liu | + 1192 word(s) | 1192 | 2021-05-18 10:11:35 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | + 1 word(s) | 1193 | 2021-05-27 03:49:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

Artificial domestication and improvement of the majority of crops began approximately 10,000 years ago, in different parts of the world, to achieve high productivity, good quality, and widespread adaptability. It was initiated from a phenotype-based selection by local farmers and developed to current biotechnology-based breeding to feed over 7 billion people. For most cereal crops, yield relates to grain production, which could be enhanced by increasing grain number and weight. Grain number is typically determined during inflorescence development. Many mutants and genes for inflorescence development have already been characterized in cereal crops. Therefore, optimization of such genes could fine-tune yield-related traits, such as grain number. With the rapidly advancing genome-editing technologies and understanding of yield-related traits, knowledge-driven breeding by design is becoming a reality.

1. Introduction

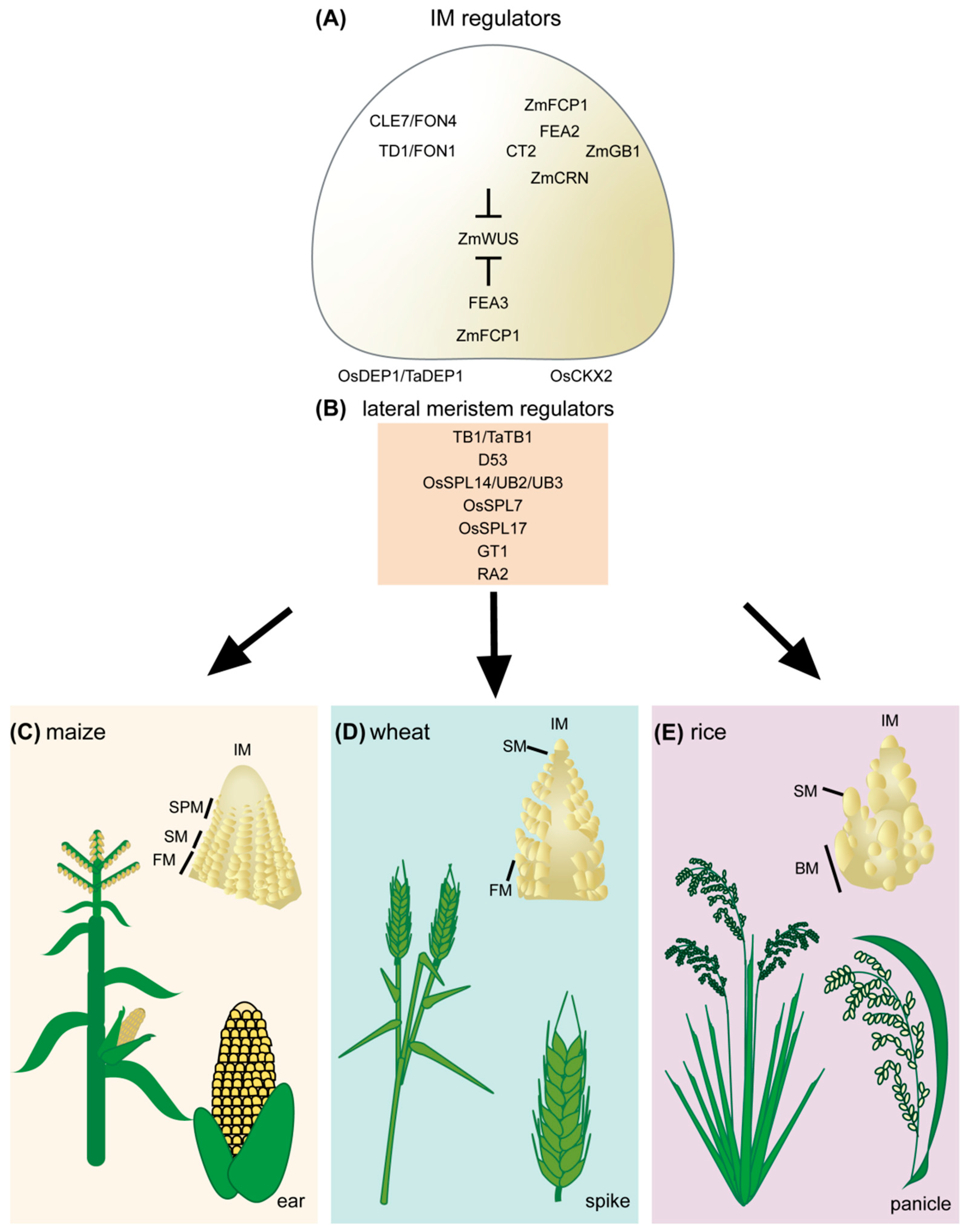

Figure 1. Regulators of cereal inflorescence development. (A) Inflorescence meristem regulators include the receptor and receptor-like proteins TD1/FON1, FEA2, and FEA3. These proteins perceive secreted CLE peptides, including ZmCLE7/FON4 and ZmFCP1. Perception of CLE peptides restricts ZmWUS activity. Downstream signaling components of FEA2 include CT2, ZmCRN, and ZmGB1. The rice DEP1 G protein also contributes to inflorescence meristem regulation through OsCKX2, though it is unclear if it acts in the CLV signaling pathway. (B) Lateral meristem regulators include TB1/TaTB1, D53, OsSPL14/UB2/UB3, OsSPL7, OsSPL17, GT1, and RA2. Inflorescence development and architecture of maize (C), wheat (D), and rice (E). IM, inflorescence meristem; SPM, spikelet pair meristem; SM, spikelet meristem; FM, floral meristem; BM, branch meristem.

Figure 1. Regulators of cereal inflorescence development. (A) Inflorescence meristem regulators include the receptor and receptor-like proteins TD1/FON1, FEA2, and FEA3. These proteins perceive secreted CLE peptides, including ZmCLE7/FON4 and ZmFCP1. Perception of CLE peptides restricts ZmWUS activity. Downstream signaling components of FEA2 include CT2, ZmCRN, and ZmGB1. The rice DEP1 G protein also contributes to inflorescence meristem regulation through OsCKX2, though it is unclear if it acts in the CLV signaling pathway. (B) Lateral meristem regulators include TB1/TaTB1, D53, OsSPL14/UB2/UB3, OsSPL7, OsSPL17, GT1, and RA2. Inflorescence development and architecture of maize (C), wheat (D), and rice (E). IM, inflorescence meristem; SPM, spikelet pair meristem; SM, spikelet meristem; FM, floral meristem; BM, branch meristem.2. Challenges and Emerging Technologies for CRISPR/Cas9-Based Crop Improvement

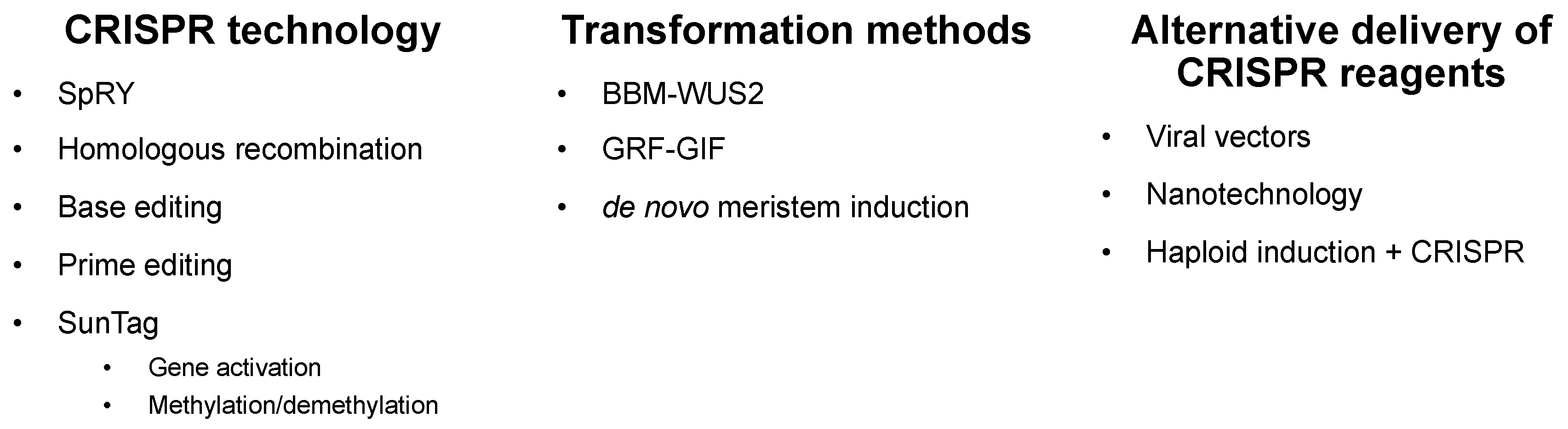

Figure 2. Recent technological advances to facilitate CRISPR/Cas9 editing in cereals. Emerging CRISPR technologies include SpRY, a mutated form of Cas9 with a relaxed PAM requirement; CRISPR base-editing, in which individual base pairs are changed; prime editing, in which a Cas9–nickase is fused to a reverse transcriptase to produce precise knock-in mutations guided by a pegRNA template; homologous recombination, where larger insertions can be introduced into a genomic region of interest; and SunTag gene activation and methylation/demethylation, where a catalytically inactive Cas9 is fused to effectors that modulate gene expression or methylation patterns. CRISPR technology can be delivered into cereals, using improved transformation methods involving developmentally important genes, such as BABYBOOM–WUSCHEL or GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR 4 and GRF-INTERACTING 1 (GRF–GIF), or through de novo meristem induction. In addition to using stable transformation to enable CRISPR editing, alternative delivery of CRISPR reagents includes the use of viral vectors, nanotechnology, and haploid induction plus CRISPR.

Figure 2. Recent technological advances to facilitate CRISPR/Cas9 editing in cereals. Emerging CRISPR technologies include SpRY, a mutated form of Cas9 with a relaxed PAM requirement; CRISPR base-editing, in which individual base pairs are changed; prime editing, in which a Cas9–nickase is fused to a reverse transcriptase to produce precise knock-in mutations guided by a pegRNA template; homologous recombination, where larger insertions can be introduced into a genomic region of interest; and SunTag gene activation and methylation/demethylation, where a catalytically inactive Cas9 is fused to effectors that modulate gene expression or methylation patterns. CRISPR technology can be delivered into cereals, using improved transformation methods involving developmentally important genes, such as BABYBOOM–WUSCHEL or GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR 4 and GRF-INTERACTING 1 (GRF–GIF), or through de novo meristem induction. In addition to using stable transformation to enable CRISPR editing, alternative delivery of CRISPR reagents includes the use of viral vectors, nanotechnology, and haploid induction plus CRISPR.3. Future Prospects

References

- Ross-Ibarra, J.; Morrell, P.L.; Gaut, B.S. Plant Domestication, a Unique Opportunity to Identify the Genetic Basis of Adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104 (Suppl. S1), 8641–8648.

- Yu, H.; Li, J. Short- and Long-Term Challenges in Crop Breeding. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8.

- Smýkal, P.; Nelson, M.N.; Berger, J.D.; Von Wettberg, E.J.B. The Impact of Genetic Changes during Crop Domestication. Agronomy 2018, 8, 119.

- Fernie, A.R.; Yan, J. De Novo Domestication: An Alternative Route toward New Crops for the Future. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 615–631.

- Baenziger, P.S.; Russell, W.K.; Graef, G.L.; Campbell, B.T. Improving Lives: 50 Years of Crop Breeding, Genetics, and Cytology (C-1). Crop Sci. 2006, 46, 2230–2244.

- Lee, E.A.; Tracy, W.F. Modern Maize Breeding. Handb. Maize Genet. Genomics 2009, II, 141–160.

- Brown, P.J.; Upadyayula, N.; Mahone, G.S.; Tian, F.; Bradbury, P.J.; Myles, S.; Holland, J.B.; Flint-garcia, S.; Mcmullen, M.D.; Buckler, E.S.; et al. Distinct Genetic Architectures for Male and Female Inflorescence Traits of Maize. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002383.

- Liu, L.; Du, Y.; Huo, D.; Wang, M.; Shen, X.; Yue, B.; Qiu, F.; Zheng, Y.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Z. Genetic Architecture of Maize Kernel Row Number and Whole Genome Prediction. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128.

- Xiao, Y.; Tong, H.; Yang, X.; Xu, S.; Pan, Q.; Qiao, F.; Raihan, M.S.; Luo, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Dissection of the Maize Ear Genetic Architecture Using Multiple Populations. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1095–1106.

- Li, M.; Zhong, W.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z. Genetic and Molecular Mechanisms of Quantitative Trait Loci Controlling Maize Inflorescence Architecture. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 448–457.

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, Q. Genetic and Molecular Bases of Rice Yield. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 421–442.

- Wang, Y.; Li, J. Branching in Rice. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 94–99.

- Tu, C.; Li, T.; Liu, X. Genetic and Epigenetic Regulatory Mechanism of Rice Panicle Development. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2079.

- Gao, X.Q.; Wang, N.; Wang, X.L.; Zhang, X.S. Architecture of Wheat Inflorescence: Insights from Rice. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24, 802–809.

- Tanaka, W.; Pautler, M.; Jackson, D.; Hirano, H.-Y. Grass Meristems II—Inflorescence Architecture, Flower Development and Meristem Fate. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013, 54, 313–324.

- Rodríguez-Leal, D.; Lemmon, Z.H.; Man, J.; Bartlett, M.E.; Lippman, Z.B. Engineering Quantitative Trait Variation for Crop Improvement by Genome Editing. Cell 2017, 171, 470–480.e8.

- Liu, L.; Gallagher, J.; Arevalo, E.D.; Chen, R.; Skopelitis, T.; Wu, Q.; Bartlett, M.; Jackson, D. Enhancing Grain-Yield-Related Traits by CRISPR—Cas9 Promoter Editing of Maize CLE Genes. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 287–294.

- Wang, X.; Aguirre, L.; Rodríguez-leal, D.; Hendelman, A. Dissecting Cis- Regulatory Control of Quantitative Trait Variation in a Plant Stem Cell Circuit. Nat. Plants 2021, 7, 419–427.

- Hendelman, A.; Zebell, S.; Rodriguez-leal, D.; Eshed, Y.; Efroni, I.; Lippman, Z.B.; Hendelman, A.; Zebell, S.; Rodriguez-leal, D.; Dukler, N.; et al. Conserved Pleiotropy of an Ancient Plant Homeobox Gene Uncovered by Cis- Regulatory Dissection Article Conserved Pleiotropy of an Ancient Plant Homeobox Gene Uncovered by Cis- Regulatory Dissection. Cell 2021.

- Cui, Y.; Hu, X.; Liang, G.; Feng, A.; Wang, F.; Ruan, S.; Dong, G.; Shen, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; et al. Production of Novel Beneficial Alleles of a Rice Yield-related QTL by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020.

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A Programmable Dual RNA-Guided DNA Endonuclease in Adaptive Bacterial Immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821.

- Zhu, C.; Bortesi, L.; Baysal, C.; Twyman, R.M.; Fischer, R.; Capell, T.; Schillberg, S.; Christou, P. Characteristics of Genome Editing Mutations in Cereal Crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 38–52.

- Trung, K.H.; Tran, Q.H.; Bui, N.H.; Tran, T.T.; Luu, K.Q.; Tran, N.T.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, D.T.N.; Vu, B.D.; Quan, D.T.T.; et al. A Weak Allele of FASCIATED EAR 2 (FEA2) Increases Maize Kernel Row Number (KRN) and Yield in Elite Maize Hybrids. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1774.

- Liu, H.-J.; Jian, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Jin, M.; Peng, Y.; Yan, J.; Han, B.; Liu, J.; et al. High-Throughput CRISPR/Cas9 Mutagenesis Streamlines Trait Gene Identification in Maize[OPEN]. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1397–1413.

- Yu, H.; Lin, T.; Meng, X.; Du, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, M.; Jing, Y.; Kou, L.; Li, X.; et al. A Route to de Novo Domestication of Wild Allotetraploid Rice Article A Route to de Novo Domestication of Wild Allotetraploid Rice. Cell 2021, 184, 1–15.