Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alba Di Leone | + 2221 word(s) | 2221 | 2021-05-20 09:23:50 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2221 | 2021-05-27 03:23:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Di Leone, A. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10111 (accessed on 07 January 2026).

Di Leone A. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10111. Accessed January 07, 2026.

Di Leone, Alba. "Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10111 (accessed January 07, 2026).

Di Leone, A. (2021, May 26). Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/10111

Di Leone, Alba. "Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Breast Cancer." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 May, 2021.

Copy Citation

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy is increasingly being employed in the management of breast cancer patients. To ensure that health care needs are adequately addressed, clinicians must consider that women with breast cancer have a high risk of developing “unmet needs” during treatment, and often require a clinical intervention or additional care resources to limit possible complications and psychological issues that can occur during neoadjuvant treatment.

breast cancer

neoadjuvant chemotherapy

multidisciplinary treatment

evidence-based medicine

personalized treatment

oncological outcomes

patient quality of life

1. Introduction

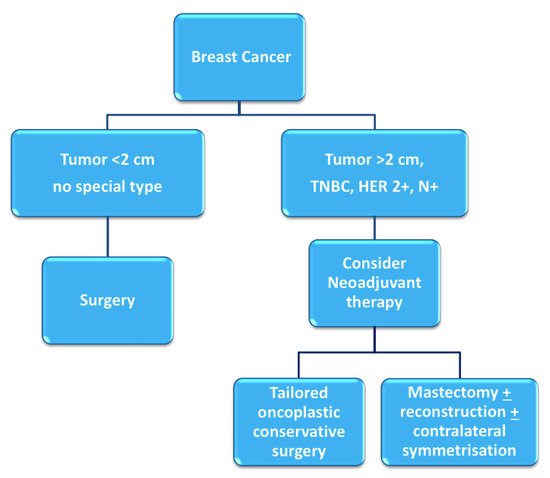

Breast cancer patients that exhibit high tumor-to-breast volume ratio, lymph node-positive disease, and aggressive biological features (high grade, hormone receptor-negative, HER2-positive, triple negative characterization) are more often candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). Although large clinical trials have shown no differences in terms of overall and disease-free survival between adjuvant and neoadjuvant systemic therapy, NAC may provide important advantages [1][2]: tumor chemosensitivity can be assessed in vivo by monitoring the response to therapy, potentially allowing for the switching of therapies in case of non-responsiveness; downstaging of tumors often allows clinicians to favor breast-conserving surgery (BCS) over mastectomy and contain excision volumes, thus improving cosmetic results; downstaging of the axilla can allow for the avoidance of lymph node dissection in selected patients, reducing surgical morbidity [3] (Figure 1). Therapeutic regimens include anthracyclines (epirubicin, 100 mg/m2), cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2; triweekly for 4 cycles) and taxanes (docetaxel, 70 mg/m2; triweekly for 4 cycles); or carboplatin (100 mg/m2; weekly for 12 cycles); taxanes are combined with targeted trastuzumab therapy in case of HER2-positivity.

Figure 1. Decision-making process for neoadjuvant chemotherapy [4].

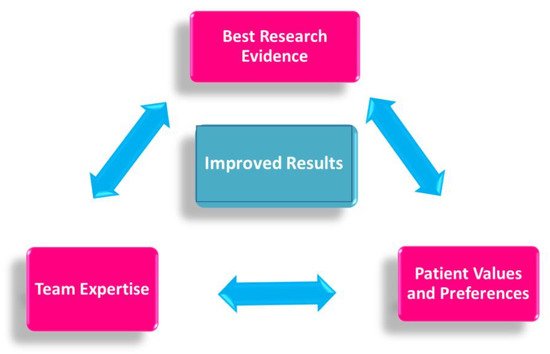

Specific evidence-based guidelines have been released to ensure that each patient treated in the neoadjuvant setting may receive the most effective, evidence-based chemotherapy regimen, in a personalized, multidisciplinary setting (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Evidence-based medicine in neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Less attention has been devoted to addressing the specific “unmet needs” that patients may experience during treatment [5]. The benefits of a multimodal prehabilitation model are still emerging in recent studies, particularly during the preoperative period. During this window of opportunity, patients may be more receptive to health behavior changes in a structured support network [6].

2. The Neoadjuvant Oncologic Treatment Team

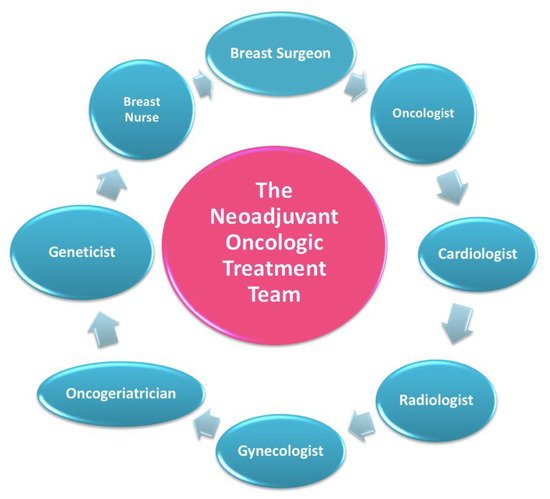

In this setting, patients are welcomed by a team of experts consisting of a breast surgeon together with the patient’s referring oncologist and breast nurse (Figure 3) [7].

Figure 3. The neoadjuvant oncologic treatment team.

This treatment team is in charge of reviewing the diagnostic workup, discussing the therapeutic plan, and explaining, scheduling, and monitoring additional interventions that may be relevant according to the age and specific medical features of each individual patient.

As a first step, the oncologic team reviews the diagnostic workup and schedules any additional appointments that may be required to complete it.

Every patient undergoing NAC in our breast center must have completed a full diagnostic panel that includes [8]:

-

Clinical breast examination, mammography, breast ultrasound, and breast MRI;

-

Ultrasound- or stereotactic-guided tissue sampling of breast lesions and suspicious lymph nodes. Markers are positioned in the breast tissue and pathologic lymph nodes in order to ensure a correct pre-surgical localization in case of pathologic complete response or regression to a non-palpable lesion;

-

Complete histopathological and prognostic characterization (ER, PgR, AR, Ki67, HER2 status);

-

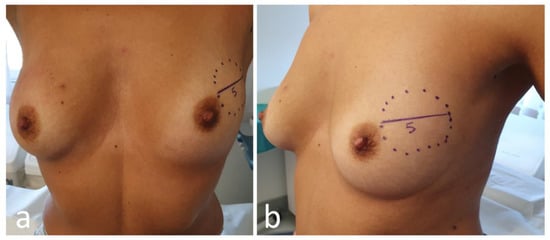

Photographical documentation of pre-NAC patient breasts. After clinical and ultrasound evaluation, the surgeon draws the tumor’s projection and measurements on the skin surface and takes two photographs in frontal and lateral projection (Figure 4). Pictures are re-evaluated after NAC and assist in surgical planning [9];

-

Systemic staging is completed by performing either a whole-body CT scan and bone scintigraphy, or a PET/CT scan.

Figure 4. Frontal (a) and lateral (b) view of pre-neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) breast with tumor projection and measurement (cm).

The team then reviews with the patient the global therapeutic plan [10]. The oncologist discusses with the patient the details of the chemotherapeutic regimen (previously defined at the MDM) and a date for the first session of NAC is set. An appointment for central venous catheter placement is also provided.

Based on age, general conditions, family history, and pathologic features of the tumor, the following additional interventions are discussed and eventually scheduled.

2.1. Cardiovascular Assessment

As conventional chemotherapy and targeted therapies are associated with an increased risk of cardiac damage [11], each patient scheduled for NAC undergoes preliminary cardiovascular assessment.

The development of cardiotoxicity, even if asymptomatic, not only adversely affects patient cardiac prognosis, but may significantly limit the proper completion of therapeutic protocols, especially if additional anticancer treatments become necessary after recovery/relapse of the disease [12]. Cardiovascular disease is now the second leading cause of long-term morbidity and mortality among cancer survivors, and the leading cause of death among female breast cancer survivors [13].

Our protocol ensures that a cardio-oncologist evaluates the patient via electrocardiogram and echocardiography before beginning treatment, and then periodically in relation to personal risk and ongoing pharmacological treatment. An adequate preliminary stratification of cardiotoxicity risk and the early identification and treatment of subclinical cardiac damage may help to avoid withdrawal of chemotherapy and prevent irreversible cardiovascular dysfunction.

2.2. Genetic Counselling

Because of recent media and popular culture coverage, general knowledge about breast cancer genetics has increased in recent years [14]. Genetic test results have also become increasingly relevant in selecting the most effective systemic therapy, thanks to the advent of PARP inhibitors for treatment of BRCA1/2-associated breast cancers. Genetic assessment has become equally relevant for the optimization of radiation therapy, with emerging concerns about radiation safety for the carriers of certain pathogenic mutations (e.g., TP53) [15].

In our model, indications to genetic testing are discussed for every patient during the MDM, taking into account patient age, family history, and the clinical features of the disease. If, according to current Italian and American guidelines [16][17], genetic testing is considered appropriate, an interview with the clinical geneticist is immediately scheduled [18]. The advantage of this approach is that patients who then undergo NAC have approximately six months to complete a full, well-rounded genetic evaluation before the scheduling of surgery. This allows us to tailor surgical choices based on the test results, avoiding the unnecessary double surgery that could derive from a positive test result obtained after breast-conserving surgery [19].

2.3. Multiparametric Geriatric Assessment in Elderly Patients

Elderly patients represent a very heterogeneous community in terms of life expectancy, comorbidities, and cognitive and social function, therefore it is crucial not to deny treatment based on age alone. In this framework, a multiparametric geriatric assessment is always appropriate, and is a convenient supplement in the evaluation of every elderly patient treated for breast cancer, as it can move the needle on proposed treatment.

A recent study by Okonji et al. reported that nearly 50% of fit elderly women with high-risk disease are undertreated [20]. The neoadjuvant use of chemotherapy is further neglected, with studies reporting higher toxicity rates and lower incidence of complete pathological response in patients aged over 65 [21]. However, although elderly patients are generally underrepresented in clinical trials, those with non-triple negative breast cancer show a prognosis comparable to younger patients in terms of overall survival [22]. An individualized care model must therefore be applied to select the elderly sub-population that could benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and monitor it closely during treatment to prevent toxicity in these fragile patients [23].

In our protocol, patients aged 70 years or older, whether or not they exhibit relevant comorbidities, are scheduled for a pre-treatment comprehensive geriatric assessment. The assessment is performed by a dedicated geriatrician with experience in breast oncology, who actively participates in our multidisciplinary team. Comorbidities, cognitive and psychological disorders, physical performance, risk factors, nutritional status, and general autonomy are comprehensively evaluated, and NAC is scheduled only in the event of oncogeriatric clearance. A second assessment is also scheduled at the end of chemotherapy.

2.4. Gynecologic and Fertility Counselling in Younger Patients

Chemotherapy and/or ovarian suppression can cause early (permanent or temporary) menopausal symptoms and reduce fertility. Many women are concerned about these issues, and it is important to provide them with proper counseling and treatment [24]. As regards menopausal symptoms, a large number of patients find these difficult to cope with, with a significant negative impact on their quality of life. Our gynecologists manage these symptoms using both traditional medicine and integrative care.

Fertility care should follow a multidisciplinary team-based approach, with strict interaction between medical oncologists, surgeons, and fertility specialists [25][26]. In our multidisciplinary prehabilitation care model, the main goal is to preserve the opportunity for family planning, offering oncofertility services in a timely manner without delaying chemotherapy.

The breast nurse follows the patient on this pathway and during the subsequent procedures for ovarian function and/or fertility preservation.

3. The Neoadjuvant Supportive Care Team

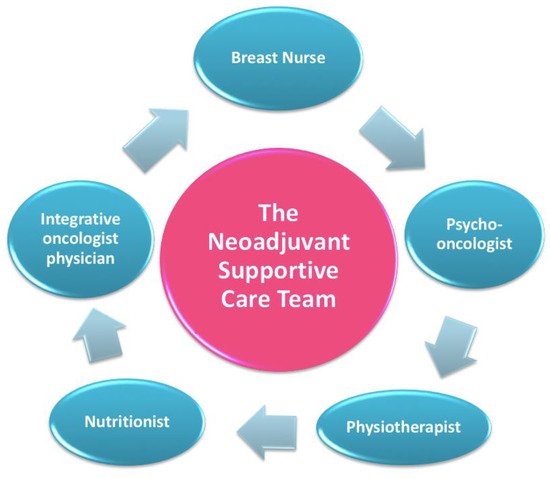

After completing the assessment with the “oncological treatment team”, every patient is directed to a meeting with the “neoadjuvant supportive care team”, which includes a nutritionist, a psycho-oncologist, and an integrative oncology expert (Figure 5) [27].

Figure 5. The neoadjuvant supportive care team.

A lifestyle interview is conducted, and anthropometric parameters and body composition analysis are measured via segmental multi frequency–bioelectrical impedance analysis (SMF-BIA).

Nutritional and physical activity screenings are performed in our unit just before the beginning and at the conclusion of oncologic treatments, and the impact of each type of intervention, from surgery to chemotherapy, on BMI, body composition, and metabolism is monitored during therapy. In this regard, patients are asked to keep a diary and send it regularly via email, and periodic video interviews are scheduled [28][29][30].

3.1. Lifestyle and Nutrition Counseling

Physical activity (PA), nutrition, body weight, and metabolism all play a key role in almost every aspect of cancer onset, progression, and management [31] (WCRF -World Cancer Research Fund 2018). However, nutritional screening is seldom performed even in high-quality breast units, and data on its value are still scarce [32][33][34].

Specific recommendations about diet and physical activity based on the most recent scientific evidence [31] are given to all patients, with the aim of relieving chemotherapy toxicity and improving quality of life and oncological outcomes [35][36]. Moreover, during and after treatments, patients are supported by a personalized nutritional approach and motivated to practice PA in order to decrease their disease recurrence risk [35][37]. PA during cancer treatments represents a powerful asset to improve therapy-induced conditions such as anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, lymphedema, cancer- and therapy-related fatigue, bone health, and overall quality of life [38][39][40][41][42].

3.2. Psychological Counselling

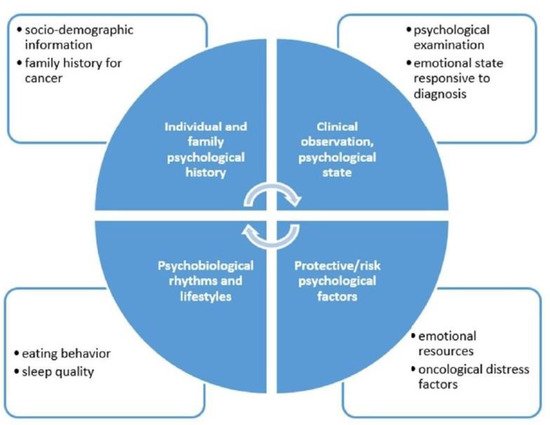

Chemotherapy generates a distress that, over time, can severely affect patient quality of life [43][44]. A recent study showed that post-NAC patients have a significantly higher level of distress compared to patients receiving chemotherapy after surgery [45]. Understanding the needs of patients undergoing NAC enables us to address the communication process more appropriately, provide psychological support, and build clinical and rehabilitation interventions in a more personalized way [43]. In line with NCCN guidelines, the diagnostic and therapeutic pathways of patients scheduled for NAC include a pre–post treatment psychological evaluation. Specific, psycho-oncological support should be given to patients undergoing chemotherapy. At the beginning of NAC, patients undergo a clinical psychological interview aimed at assessing their risk of oncological distress, and identifying both the dysfunctional psychological factors and the protective psychosocial factors that could affect treatment. The goal is to improve adaptation to the oncological disease and promote adherence to therapeutic treatments. In addition to the interview, a psychometric assessment is carried out through screening and the employment of clinical tools such as the Distress Thermometer (DT) [46], the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) [47] and the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES) [48].

In our breast center, we aim to validate a semi-structural interview, which leads to a holistic and trans-disciplinary measurement of the psychological state of the patients. The assessment allows us to identify patients who may benefit from a psychological support intervention, individual psychotherapy, or group therapy [49] (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Psychological interview.

3.2.1. Emotional Eating Prevention during NAC

The impact of psychosocial factors such as worry, perceived risk, and perceived treatment efficacy on diet has been understudied in breast cancer patients [50]. The relationship between distress, weight change, and nutrition has been the subject of a fairly recent psycho-oncological study trend, with major studies conducted on patients at the end of their therapies. Our model proposes an integrative approach to identify emotional eating, a dietary pattern wherein people use food to help them deal with stressful situations and in response to negative emotions. Overweight individuals have been found to exhibit less effective coping skills in response to negative emotions, which leads them to emotionally eat more frequently [51]. Psychological disciplines can help to identify healthy and harmful habits, and promote changes in attitudes and healthy behaviors.

Psychological intervention based on the activation of self-efficacy in dietary behavior could favor the ability to adapt to oncological therapies through active participation in treatment, redefinition of problems, and the evaluation of alternative solutions. At the same time, the intervention acts in support of lifestyle changes and involves the activation of specific psychoeducational groups for patients who need to change their dietary behavior.

3.3. Integrative Oncology during Neoadjuvant Therapy

Our patients receive information about evidence-based complementary therapies available, in order to optimize the management of symptoms related either to the disease itself or to treatment toxicity: most frequently gastro-intestinal disorders, hot flashes, fatigue, insomnia, mucositis, peripheral neuropathy, anxiety, and mood disorders.

In accordance with the SIO (Society of Integrative Oncology) clinical guidelines for breast cancer patients [52] recently endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) [53], personalized integrative care plans at the FPG Center for Integrative Oncology include mind–body interventions such as acupuncture, mindfulness-based protocols, qi gong, massage therapy, and other group programs like music therapy, art therapy, and therapeutic writing workshops.

References

- Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Long-Term outcomes for neoadjuvant versus adjuvant chemotherapy in early breast cancer: Meta-Analysis of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 27–39.

- O’Halloran, N.; Lowery, A.; Curran, C.; McLaughlin, R.; Malone, C.; Sweeney, K.; Keane, M.; Kerin, M. A Review of the impact of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on breast surgery practice and outcomes. Clin. Breast Cancer 2019, 19, 377–382.

- Franceschini, G.; Di Leone, A.; Natale, M.; Sanchez, A.M.; Masetti, R. Conservative surgery after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2018, 89, 290.

- Franceschini, G.; Visconti, G.; Masetti, R. Oncoplastic breast surgery with oxidized regenerated cellulose: Appraisals based on five-year experience. Breast J. 2014, 20, 447–448.

- Lo-Fo-Wong, D.N.; de Haes, H.C.; Aaronson, N.K.; van Abbema, D.L.; den Boer, M.D.; van Hezewijk, M.; Immink, M.; Kaptein, A.A.; Menke-Pluijmers, M.B.; Reyners, A.K.; et al. Risk factors of unmet needs among women with breast cancer in the post-treatment phase. Psychooncology 2020, 29, 539–549.

- Brahmbhatt, P.; Sabiston, M.C.; Lopez, C.; Chang, E.; Goodman, J.; Jones, J.; McCready, D.; Randall, I.; Rotstein, S.; Santa Mina, D. Feasibility of prehabilitation prior to breast cancer surgery: A mixed-methods study. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10.

- Shao, J.; Rodrigues, M.; Corter, A.L.; Baxter, N.N. Multidisciplinary care of breast cancer patients: A scoping review of multidisciplinary styles, processes, and outcomes. Curr. Oncol. 2019, 26, e385–e397.

- Franceschini, G.; Terribile, D.; Fabbri, C.; Magno, S.; D’Alba, P.; Chiesa, F.; Di Leone, A.; Masetti, R. Management of locally advanced breast cancer: Mini-Review. Minerva Chir. 2007, 62, 249–255.

- Salgarello, M.; Visconti, G.; Barone-Adesi, L.; Franceschini, G.; Masetti, R. Contralateral breast symmetrisation in immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction after unilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy: The tailored reduction/augmentation mammaplasty. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2015, 42, 302–308.

- Franceschini, G.; Sanchez, A.M.; Di Leone, A.; Magno, S.; Moschella, F.; Accetta, C.; Natale, M.; Di Giorgio, D.; Scaldaferri, A.; D’Archi, S.; et al. Update on the surgical management of breast cancer. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2015, 86, 89–99.

- Shan, K.; Lincoff, A.M.; Young, J.B. Anthracycline-Induced cardiotoxicity. Ann. Intern. Med. 1996, 125, 47–58.

- Felker, G.M.; Thompson, R.E.; Hare, J.M.; Hruban, R.H.; Clemetson, D.E.; Howard, D.L.; Baughman, K.L.; Kasper, E.K. Underlying causes and long-term survival in patients with initially unexplained cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1077–1084.

- Patnaik, J.L.; Byers, T.; DiGuiseppi, C.; Dabelea, D.; Denberg, T.D. Cardiovascular disease competes with breast cancer as the leading cause of death for older females diagnosed with breast cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R64.

- Tischler, J.; Crew, K.D.; Chung, W.K. Cases in precision medicine: The role of tumor and germline genetic testing in breast cancer management. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 925–930.

- Katz, S.J.; Ward, K.C.; Hamilton, A.S.; McLeod, M.C.; Wallner, L.P.; Morrow, M.; Jagsi, R.; Hawley, S.T.; Kurian, A.W. Gaps in receipt of clinically indicated genetic counseling after diagnosis of breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1218–1224.

- Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica (AIOM). Neoplasia della Mammella; Linee Guida; Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica (AIOM): Milano, Italy, 2020.

- Gradishar, W.J.; Anderson, B.O.; Abraham, J.; Aft, R.; Agnese, D.; Allison, K.H.; Blair, S.L.; Burstein, H.J.; Dang, C.; Elias, A.; et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology—Breast Cancer; National Comprehensive Cancer NetworkNCCN: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2020.

- Christian, N.; Zabor, E.C.; Cassidy, M.; Flynn, J.; Morrow, M.; Gemignani, M.L. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy use after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 743–749.

- Terkelsen, T.; Rønning, H.; Skytte, A.B. Impact of genetic counseling on the uptake of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy among younger women with breast cancer. Acta Oncol. 2020, 59, 60–65.

- Okonji, D.O.; Sinha, R.; Phillips, I.; Fatz, D.; Ring, A. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in 326 older women with early breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 117, 925–931.

- Halfter, K.; Ditsch, N.; Kolberg, H.C.; Fischer, H.; Hauzenberger, T.; von Koch, F.E.; Bauerfeind, I.; von Minckwitz, G.; Funke, I.; Crispin, A.; et al. Prospective cohort study using the breast cancer spheroid model as a predictor for response to neoadjuvant therapy—The SpheroNEO study. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 519.

- von Waldenfels, G.; Loibl, S.; Furlanetto, J.; Machlei, A.; Lederer, B.; Denkert, C.; Hanusch, C.; Kümmel, S.; von Minckwitz, G.; Schneeweiss, A.; et al. Outcome after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in elderly breast cancer patients—A pooled analysis of individual patient data from eight prospectively randomized controlled trials. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 15168–15179.

- Hurria, A.; Togawa, K.; Mohile, S.G.; Owusu, C.; Klepin, H.D.; Gross, C.P.; Lichtman, S.M.; Gajra, A.; Bhatia, S.; Katheria, V.; et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A prospective multicenter study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3457–3465.

- Arecco, L.; Perachino, M.; Damassi, A.; Latocca, M.M.; Soldato, D.; Vallome, G.; Parisi, F.; Razeti, M.G.; Solinas, C.; Tagliamento, M.; et al. Burning questions in the oncofertility counseling of young breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Basic Clin. Res. 2020, 14.

- Peccatori, F.A.; Azim, H.A.; Orecchia, R.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Pavlidis, N.; Kesic, V.; Pentheroudakis, G. Pentheroudakis, Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24 (Suppl. 6), vi160–vi170.

- Oktay, K.; Harvey, B.E.; Partridge, A.H.; Quinn, G.P.; Reinecke, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Wallace, W.H.; Wang, E.T.; Loren, A.W. Fertility preservation in patients with cancer: ASCO clinical practice guideline update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1994–2001.

- Magno, S.; Alessio, F.; Scaldaferri, A.; Sacchini, V.; Chiesa, F. Integrative approaches in breast cancer patients: A mini-review. Integr. Cancer Sci. Ther. 2016, 3, 460–464.

- Bozzetti, F.; Arends, J.; Lundholm, K.; Micklewright, A.; Zurcher, G.; Muscaritoli, M. ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: Non-Surgical oncology. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 28, 445–454.

- Kondrup, J.E.; Allison, S.P.; Elia, M.; Vellas, B.; Plauth, M. ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 415–421.

- Ryan, A.M.; Power, D.G.; Daly, L.; Cushen, S.J.; Ní Bhuachalla, E.; Prado, C.M. Cancer-Associated malnutrition, cachexia and sarcopenia: The skeleton in the hospital closet 40 years later. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 199–211.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Continous Update Project Report: Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Breast Cancer; World Cancer Research Fund International: London, UK, 2018; Available online: (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Prado, C.M.M.; Baracos, V.E.; McCargar, L.J.; Reiman, T.; Mourtzakis, M.; Tonkin, K.; Mackey, J.R.; Koski, S.; Pituskin, E.; Sawyer, M.B. Sarcopenia as a determinant of chemotherapy toxicity and time to tumor progression in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving capecitabine treatment. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2920–2926.

- Carbognin, L.; Trestini, I.; Sperduti, I.; Bonaiuto, C.; Zambonin, V.; Fiorio, E.; Tregnago, D.; Parolin, V.; Pilotto, S.; Scambia, G.; et al. Prospective trial in early-stage breast cancer (EBC) patients (pts) submitted to nutrition evidence-based educational intervention: Early results of adherence to dietary guidelines (ADG) and body weight change (BWC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. 15), 11575.

- Iyengar, N.M.; Zhou, X.K.; Gucalp, A.; Morris, P.G.; Howe, L.R.; Giri, D.D.; Morrow, M.; Wang, H.; Pollak, M.; Jones, L.W.; et al. Systemic correlates of white adipose tissue inflammation in early-stage breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2283–2289.

- Pierce, J.P.; Stefanick, M.L.; Flatt, S.W.; Natarajan, L.; Sternfeld, B.; Madlensky, L.; Al-Delaimy, W.K.; Thomson, C.A.; Kealey, S.; Hajek, R.; et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2345–2351.

- Rock, C.L.; Thomson, C.; Gansler, T.; Gapstur, S.M.; McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.V.; Andrews, K.S.; Bandera, E.V.; Spees, C.K.; Robien, K.; et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 245–271.

- Lohse, T.; Faeh, D.; Bopp, M.; Rohrmann, S. Adherence to the cancer prevention recommendations of the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research and mortality: A census-linked cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 678–685.

- Courneya, K.S.; McKenzie, D.C.; Mackey, J.R.; Gelmon, K.; Friedenreich, C.M.; Yasui, Y.; Reid, R.D.; Cook, D.; Jespersen, D.; Proulx, C.; et al. Effects of exercise dose and type during breast cancer chemotherapy: Multicenter randomized trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013, 105, 1821–1832.

- Irwin, M.L.; Cartmel, B.; Gross, C.P.; Ercolano, E.; Li, F.; Yao, X.; Fiellin, M.; Capozza, S.; Rothbard, M.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Randomized exercise trial of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 1104–1111.

- Lee, A.; Chiu, C.H.; Cho, M.W.A.; Gomersall, C.D.; Lee, K.F.; Cheung, Y.S.; Lai, P.B.S. Factors associated with failure of enhanced recovery protocol in patients undergoing major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgery: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005330.

- Velthuis, M.J.; Agasi-Idenburg, S.C.; Aufdemkampe, G.; Wittink, H.M. The effect of physical exercise on cancer-related fatigue during cancer treatment: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 22, 208–221.

- Knols, R.; Aaronson, N.K.; Uebelhart, D.; Fransen, J.; Aufdemkampe, G. Physical exercise in cancer patients during and after medical treatment: A systematic review of randomized and controlled clinical trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 3830–3842.

- Beaver, K.; Williamson, S.; Briggs, J. Exploring patient experiences of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 20, 77–86.

- Ganz, P.A.; Desmond, K.A.; Leedham, B.; Rowland, J.H.; Meyerowitz, B.E.; Belin, T.R. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 39–49.

- Magno, S.; Carnevale, S.; Dentale, F.; Belella, D.; Linardos, M.; Masetti, R. Neo-Adjuvant chemotherapy and distress in breast cancer patients: The moderating role of generalized self-efficacy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35 (Suppl. 15), e21570.

- Gil, F.; Grassi, L.; Travado, L.; Tomamichel, M.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Zanotti, P.; Lluch, P.; Hollenstein, M.F.; Maté, J.; Magnani, K.; et al. Use of distress and depression thermometers to measure psychosocial morbidity among southern European cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2005, 13, 600–606.

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370.

- Luszczynska, A.; Scholz, U.; Schwarzer, R. The general self-efficacy scale: Multicultural validation studie. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 2005, 139, 439–457.

- Magno, S.; Filippone, A.; Scaldaferri, A. Evidence-Based usefulness of integrative therapies in breast cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2018, 7, S379–S389.

- Maunsell, E.; Drolet, M.; Brisson, J.; Robert, J.; Deschênes, L. Dietary change after breast cancer: Extent, predictors, and relation with psychological distress. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 1017–1025.

- Ozier, A.D.; Kendrick, O.W.; Leeper, J.D.; Knol, L.L.; Perko, M.; Burnham, J. Overweight and obesity are associated with emotion and stress—Related eating as measured by the eating and appraisal due to emotions and stress questionnaire. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 49–56.

- Greenlee, H.; DuPont-Reyes, M.J.; Balneaves, L.G.; Carlson, L.E.; Cohen, M.R.; Deng, G.; Johnson, J.A.; Mumber, M.; Seely, D.; Zick, S.M.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines on the evidence-based use of integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 194–232.

- Lyman, G.H.; Greenlee, H.; Bohlke, K.; Bao, T.; DeMichele, A.M.; Deng, G.E.; Fouladbakhsh, J.M.; Gil, B.; Hershman, D.L.; Mansfield, S.; et al. Integrative therapies during and after breast cancer treatment: ASCO endorsement of the SIO clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2647–2655.

More

Information

Subjects:

Obstetrics & Gynaecology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 May 2021

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No