| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Deyslen Mariano-Hernández | + 2014 word(s) | 2014 | 2020-12-03 05:16:50 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 2014 | 2020-12-09 04:28:14 | | | | |

| 3 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 2014 | 2020-12-15 06:57:57 | | |

Video Upload Options

Buildings are among the largest energy consumers in the world. As new technologies have been developed, great advances have been made in buildings, turning conventional buildings into smart buildings. These smart buildings have allowed for greater supervision and control of the energy resources within the buildings, taking steps to energy management strategies to achieve significant energy savings. The forecast of energy consumption in buildings has been a very important element in these energy strategies since it allows adjusting the operation of buildings so that energy can be used more efficiently.

1. Introduction

Energy efficiency is a general concern, from people to governments, since it yields efficient reserve funds, lessens ozone-depleting substance outflows and lightens energy requirements [1]. In recent years, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from buildings have been on the rise after a reduction between 2013 and 2016. In 2019, CO2 emissions reached a total of 10 GtCO2, the highest level recorded [2]. The decrease in building energy consumption is important to alleviate greenhouse gas emissions and help to advance sustainable building practices [3]. Noteworthy changes to decrease building operating expenses and assets arrangement may be reached through cutting-edge control techniques. Some of these techniques utilize forecasts of unsettling influences to foresee future building behavior and select an ideal arrangement of activities [4].

Forecasting is aimed at anticipating the future as precisely as possible, given the entirety of the data accessible, and is one of the most significant instruments for a proactive energy management system [5][6]. Lately, much consideration has been paid to advancement of energy utilization in the smart grid. Demand-side management is one of the prominent functions in a smart grid that enables end-clients to alter their demand for energy through different methods [7] such as building energy management systems (BEMS). BEMS were created for the efficient control and supervision of building energy utilization, allowing a decrease carbon dioxide emissions [8][9]. Over the past several decades, forecasting building energy consumption has gained importance with the development of BEMS [10][11]. The dynamic occupants’ behavior presents vulnerability issues that influence the performance of BEMS. To address this vulnerability issue, BEMS may implement forecasting as one of the BEMS modules [12].

Forecasting of building energy use is the foundation for intelligent building performance through low energy and control techniques [13]. Building energy utilization has extensive energy reserve funds potential, but it requires an exact forecast since the prediction will directly influence the control techniques and the building’s potential energy reserve funds [14].

2. Building Energy Consumption Forecasting

Building energy utilization is influenced by the building envelope, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC), occupants’ behavior and lighting [15]. Building energy forecasting can be sorted into five categories: heating energy, cooling energy, heating and cooling energy, whole-building energy and others [16]. In this research, energy consumption is studied from the electrical demand approach.

2.1. Objectives of Forecasting in Buildings

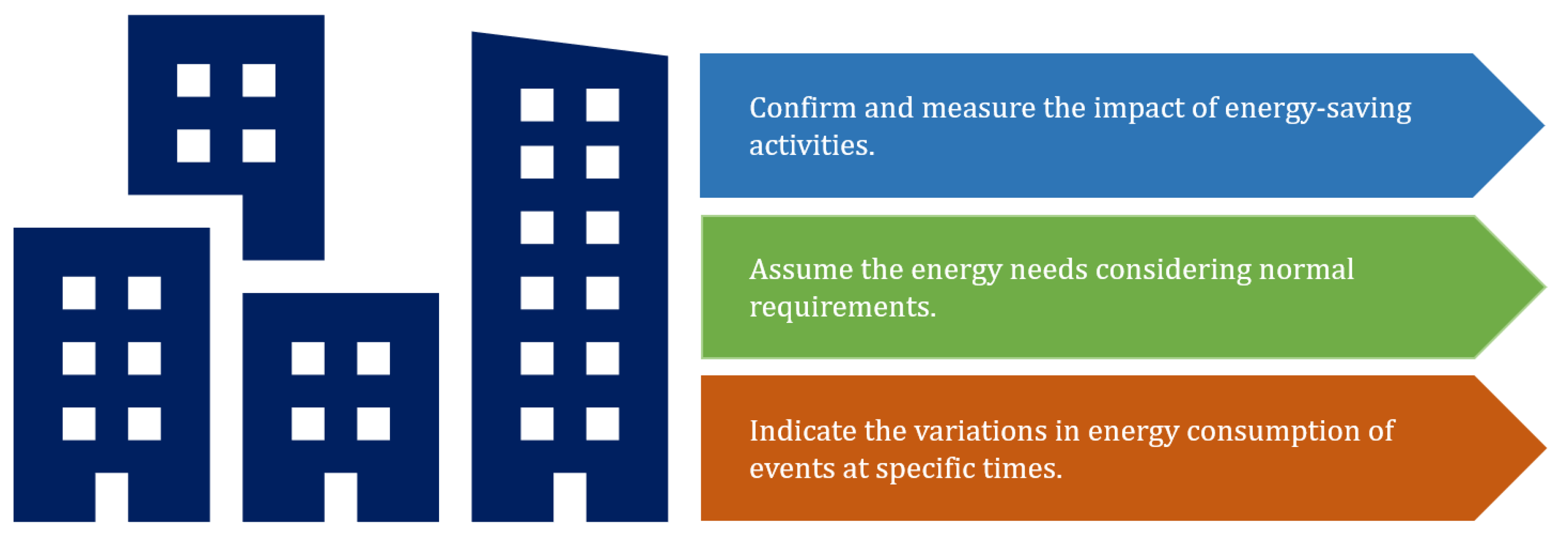

Forecasting in buildings aims to achieve different objectives (see Figure 1) such as: (a) confirm and measure the impact of energy-saving activities [17] and once the guidelines have been drawn up and implemented to obtain reductions in energy consumption, this objective pursues to validate that these guidelines have the expected results; (b) assume the energy needs considering normal requirements, which seeks to anticipate events that may modify the usual energy consumption of the systems, such as a sudden change in temperature that may affect the occupant’s comfort; and (c) indicate the variations in energy consumption of events at specific times; once an event that may alter energy consumption has occurred, this objective pursues to determine how much the variation in energy consumption would be. These forecasts can be used in the organization and distribution of goods to meet the need [18].

Building energy consumption forecasting is critical for building performance enhancements, energy management and reserves, detecting system faults and optimization of intelligent building process [19][20]. It is commonly a noteworthy segment to permit the control framework to decide ideal control settings to accomplish energy or cost investment funds. The exactness of energy use estimation legitimately impacts the general control execution and energy/cost investment funds [21]. Consequently, the more precise the prediction, the more prominent the advantages the building proprietors procure. Despite what might be expected, a vulnerability in the estimation lessens the space for efficient energy management, which brings about pointless expenses. Thus, it is important to improve energy utilization forecasting [22].

2.2. Forecasting Methods

Forecasting methods can successfully anticipate energy utilization by creating a relationship between energy and the system that consumes it by reducing the waste created by oversupply and undersupply [23]. In recent years, different techniques have been proposed to capture this knowledge in the form of predictions [24]. In the building segment, smart meters that measure and transmit energy usage are being widely installed. These open the door to new applications and results in the energy sector that allow for better forecasting accuracy [25]. Energy utilization forecasting for buildings has a huge incentive in energy proficiency and manageability research. Precise energy forecasting methods have various ramifications in arranging and energy optimization [26]. A great deal of building energy forecasting methods have been created in the previous two decades from different points of view [27].

There are three fundamental methodologies in building energy forecasting and modeling: physical, data-driven and hybrid methods [28][29]. Physical methods estimate energy use using thermodynamic rules to solve the heat and mass balance inside a building, which is also called a “white-box” as the internal logic is known [30]. Data-driven depends on time-series statistical assessments and machine learning s of rules to evaluate and estimate the building energy utilization, and is also called a black-box since it predicts energy utilization ignoring the physical characteristics of the building [31]. The hybrid method known as a grey-box, which was first presented in the 1990s to improve HVAC control frameworks’ effectiveness [32], and combines physical and data-driven methods [33][34].

Physical methods permit monitoring and modeling and investigate the cycle bit by bit where all the conditions are known [35]. However, they cannot deal with the complex energy resulting from the occupants’ behavior in this manner, bringing about huge forecast mistakes. Therefore, these models are not commonly used for exact load expectations [36]. To build up an accurate physical method, many input variables are required, which makes it complex to acquire all the necessary information. More significantly, the unsure and unreliable data suggest a difference between the model outcomes and reality [37]. There have been studies on physical methods that have focused on-the demand forecast model for several energy sources [38], namely energy consumption for a building elevator [39], electrical consumption for cooling [40][41], energy demand [42][43][44], load forecasting [45], electric and heat load [46] and heating consumption [47].

2.3. Input Variables

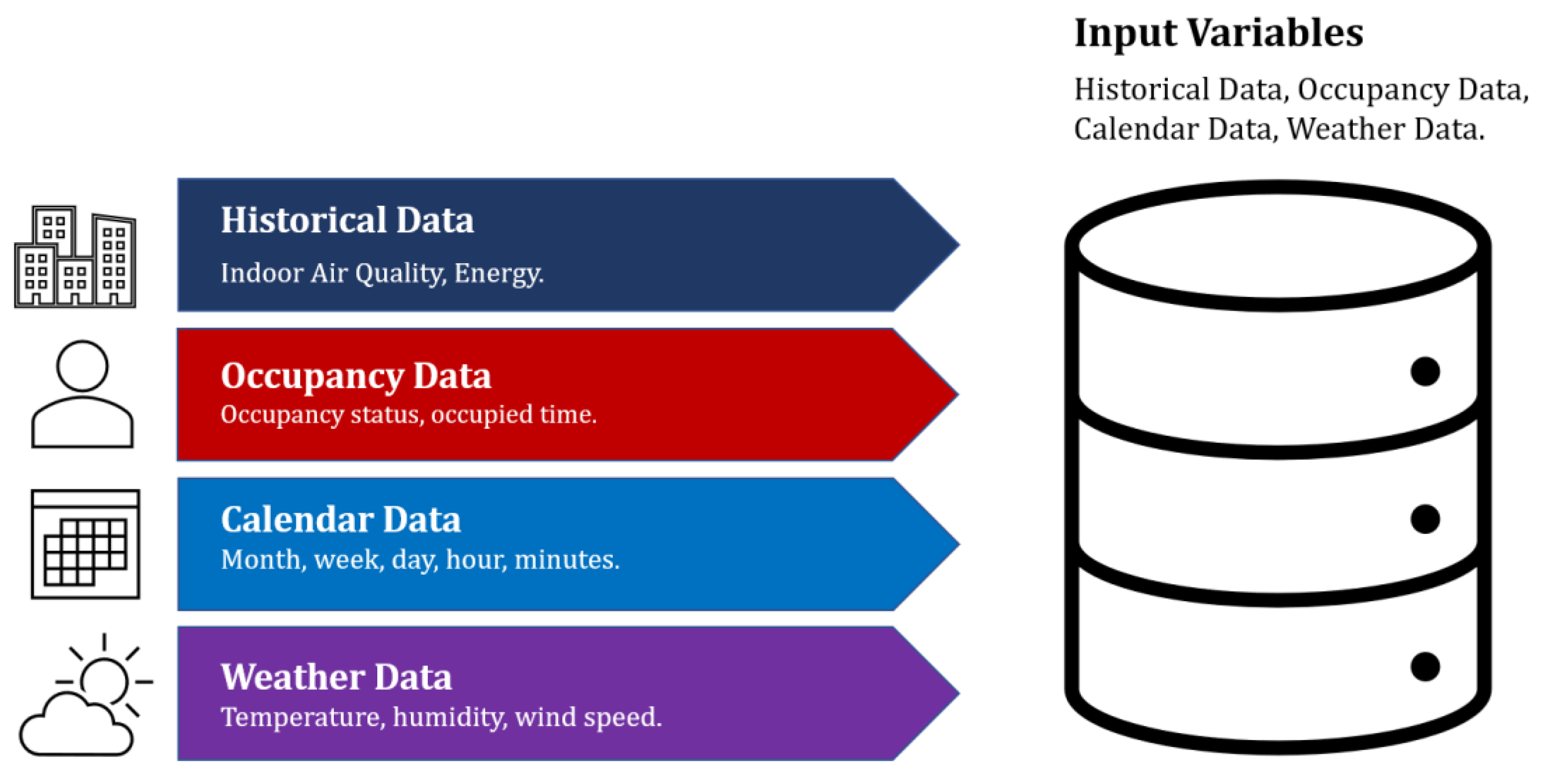

Essentially, the most significant and highly correlated input variables may bring better forecast outcomes [48]. Input variables can be categorized (see Figure 2) into historical, time type, occupancy, and climatic. Historical variables, for example, record energy as the main input, showing a load profile pattern in numerical form. Occupation variables refer to human behavior and occupation hours. Climatic variables are obtained using methods for climatic stations [49].

A significant purpose of building energy utilization estimation lies in the commitment to the input parameters and timetable data of some virtual instruments [50]. Considering that there are many estimates of a building management system, the choice of the information parameters of a model strongly influences the exposure of a model. Therefore, choosing proper factors for a building energy forecasting method could prompt better performance [51]. Effective energy forecasting requires that many key factors be anticipated [52].

2.4. Prediction Horizon

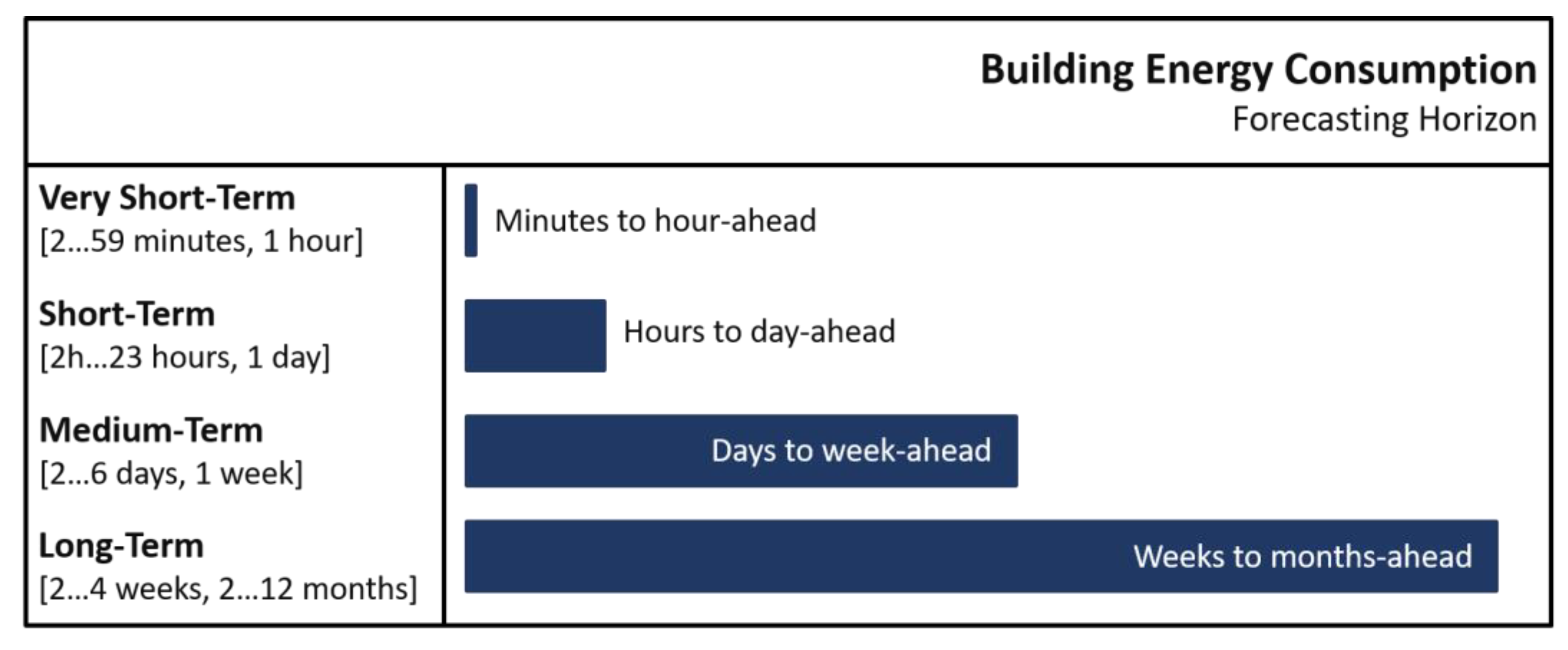

The forecasting horizon (see Figure 3) is usually classified as very short-term, short-term, medium-term and long-term. The very short-term forecast ranges from seconds or minutes to several hours [53]. Short-term extends for one hour to a week [54]. For the medium-term, the anticipating time ranges from weeks to months [55]. Long-term determination, as a rule, includes yearly forecasts of territorial or national power utilization [56]. Long term forecasting is commonly used to plan the improvement of the energy framework and to implement new appropriate production and storage systems [57]. Short and medium-term forecasts assume important tasks to promote the integration of sustainable energy sources and support more viable demand management [58][59]. Besides the forecasting horizon, the main contrast among them is the extent of the variables used: very short term utilization variables in the range of minutes or hours, short term utilization variables in the range of days, and medium and long term utilization variables in the range of weeks or even months [60].

2.5. Accuracy Metrics

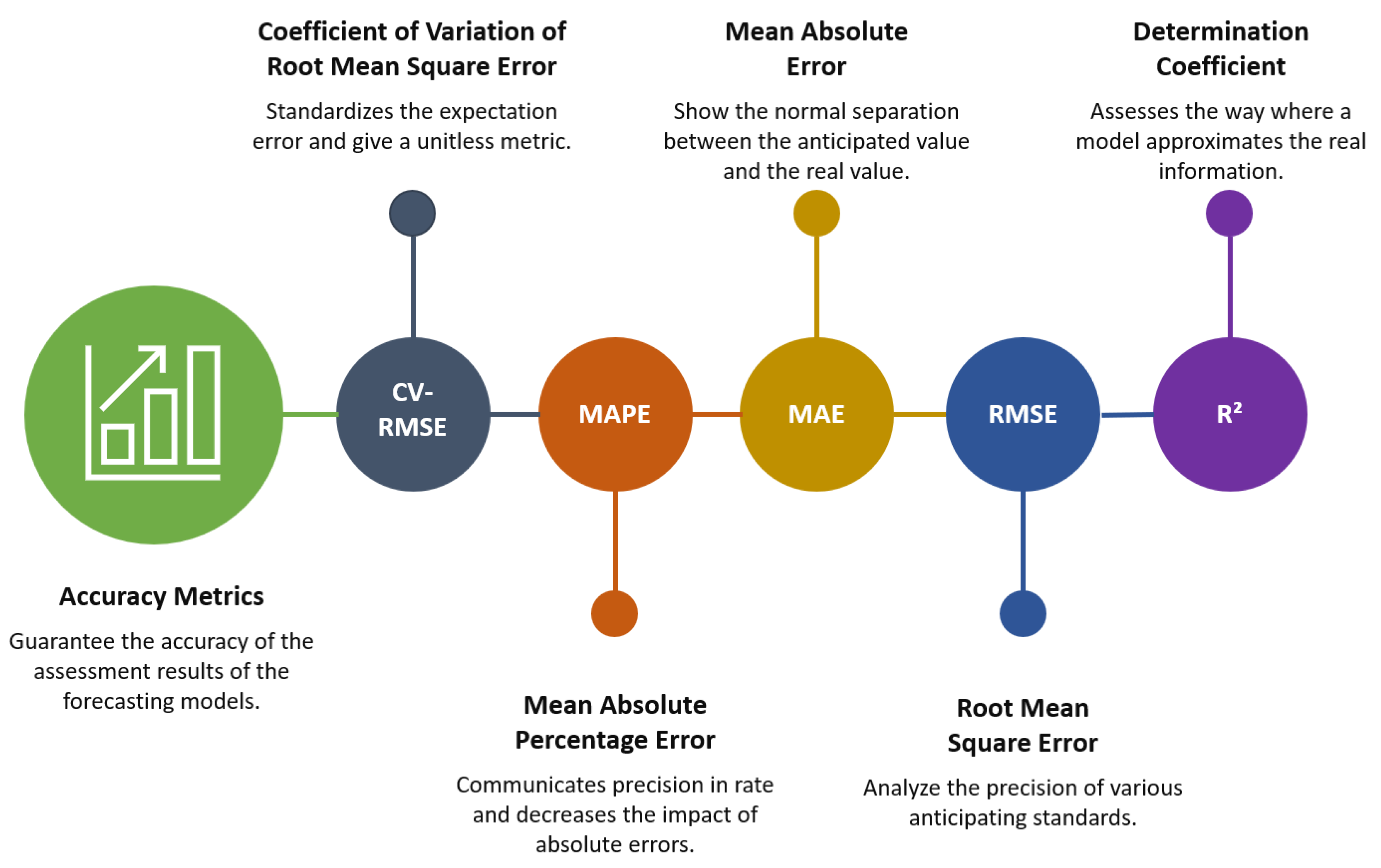

A variety of accuracy metrics are used to validate the forecasting models, the most used being (see Figure 4) coefficient of variation of root mean square error (CVRMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE) and determination coefficient (R2). Each of these metrics has a particular function. CVRMSE standardizes the expectation error and can give a helpful unitless metric. MAPE shows rate accuracy and decreases the impact of absolute errors caused by singular exceptions [61]. MAE depends on the absolute error and can show the normal separation between the anticipated value and the real value. RMSE is generally proposed as an expectation quality estimation and it is frequently used to analyze the precision of various anticipating standards [62]. The measurement punishes huge errors because it mathematically enhances mistakes [63]. R2 assesses how a model approximates the real information, giving a metric of the consistency of the model [64].

Other accuracy metrics used by several researchers are normalized mean absolute error, expect error percentage, mean Absolute, relative error, mean square error, percentage of bias, weight absolute percentage error, and Pearson correlation coefficient.

3. Future Challenges

Energy consumption forecasting is an important instrument that can help in the recognition, measurement and management of demand flexibility. In this aspect, some challenges need to be overcome in the future.

- Future lines of research should encourage the use of current methods (physical, data-driven and hybrid), allowing them to be relevant for the representation of the energy of buildings at various scales and in different environmental conditions [65]. Current methods need to address challenges such as forecast error compensation, dynamic model selection issues, adaptive predictive model design and data integrity [66].

- In some forecasting methods based on machine learning, noise-free simulation data are embraced. In this way the variety of energy performance is more predictable than that of energy simulation results [67], which lead to an overfitting or even wrong-fitting issues [68].

- Achieving high accuracy in forecasting energy use is critical to improving energy management. In any case, this requires the determination of appropriate estimation models, ready to capture the individual attributes of the array to be anticipated, which is a task that includes a lot of uncertainties [69].

- Since the energy frameworks of buildings have the essential function of meeting the needs of tenants, numerous investigations accepted a consistent schedule. For residential buildings, tenant patterns are more erratic and irregular, and the assumption of a coherent schedule is less reasonable [70]. The main causes of such inconsistencies are unrealistic inputs regarding tenant behavior and existing forecasting methods [71].

- Forecasting methods need the ability to accurately predict when space is occupied [72]. Some research is still needed on building management systems in terms of tenant behavior and choices, e.g., a collaboration between the system and tenant preferences in terms of comfort and energy use, the adaptability of these systems to tenant behavior and the extent to which they can adjust to that behavior [73].

Considering the above challenges, it would not be possible to use a single forecasting method that could be applied to any building to meet all the requirements of the different application scenarios, taking also into account the preference of the occupants. Therefore, one should think about maximizing the potential of each of the methods by using criteria to select the best one for a specific application. Building prediction methods benefit economically and environmentally by creating energy flexibility strategies such as strategic conservation, flexible load shape, peak trimming and load shifting. These strategies are highly dependent on the behavior of the occupants, so it is necessary to create models that consider the preferences and decisions of the building’s occupants, which would change depending on the nature of the building.

References

- González-Vidal, A.; Jiménez, F.; Gómez-Skarmeta, A.F. A methodology for energy multivariate time series forecasting in smart buildings based on feature selection. Energy Build. 2019, 196, 71–82.

- IEA Tracking Buildings 2020. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-buildings-2020 (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Homod, R.Z.; Togun, H.; Abd, H.J.; Sahari, K.S.M. A novel hybrid modelling structure fabricated by using Takagi-Sugeno fuzzy to forecast HVAC systems energy demand in real-time for Basra city. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 56, 102091.

- Cotrufo, N.; Saloux, E.; Hardy, J.M.; Candanedo, J.A.; Platon, R. A practical artificial intelligence-based approach for predictive control in commercial and institutional buildings. Energy Build. 2020, 206, 109563.

- Runge, J.; Zmeureanu, R. Forecasting Energy Use in Buildings Using Artificial Neural Networks: A Review. Energies 2019, 12, 3254.

- Simmons, C.R.; Arment, J.R.; Powell, K.M.; Hedengren, J.D. Proactive Energy Optimization in Residential Buildings with Weather and Market Forecasts. Processes 2019, 7, 929.

- Manasseh, E.C.; Ohno, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Mvuma, A. Distributed demand-side management optimisation for multi-residential users with energy production and storage strategies. J. Eng. 2014, 2014, 672–679.

- Manic, M.; Wijayasekara, D.; Amarasinghe, K.; Rodriguez-Andina, J.J. Building Energy Management Systems: The Age of Intelligent and Adaptive Buildings. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2016, 10, 25–39.

- Mariano-Hernández, D.; Hernández-Callejo, L.; Zorita-Lamadrid, A.; Duque-Pérez, O.; Santos García, F. A review of strategies for building energy management system: Model predictive control, demand side management, optimization, and fault detect & diagnosis. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101692.

- Amber, K.P.; Ahmad, R.; Aslam, M.W.; Kousar, A.; Usman, M.; Khan, M.S. Intelligent techniques for forecasting electricity consumption of buildings. Energy 2018, 157, 886–893.

- Moon, J.; Jung, S.; Rew, J.; Rho, S.; Hwang, E. Combination of short-term load forecasting models based on a stacking ensemble approach. Energy Build. 2020, 216, 109921.

- Nugraha, G.; Musa, A.; Cho, J.; Park, K.; Choi, D. Lambda-Based Data Processing Architecture for Two-Level Load Forecasting in Residential Buildings. Energies 2018, 11, 772.

- Zeng, A.; Ho, H.; Yu, Y. Prediction of building electricity usage using Gaussian Process Regression. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 28, 101054.

- Gao, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Fang, C.; Yin, S. Deep learning and transfer learning models of energy consumption forecasting for a building with poor information data. Energy Build. 2020, 223, 110156.

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, Y.-S.; Srebric, J. Predictions of electricity consumption in a campus building using occupant rates and weather elements with sensitivity analysis: Artificial neural network vs. linear regression. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102385.

- Ahmad, T.; Chen, H.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J. A comprehensive overview on the data driven and large scale based approaches for forecasting of building energy demand: A review. Energy Build. 2018, 165, 301–320.

- Fotopoulou, E.; Zafeiropoulos, A.; Terroso-Sáenz, F.; Şimşek, U.; González-Vidal, A.; Tsiolis, G.; Gouvas, P.; Liapis, P.; Fensel, A.; Skarmeta, A. Providing Personalized Energy Management and Awareness Services for Energy Efficiency in Smart Buildings. Sensors 2017, 17, 2054.

- Jallal, M.A.; González-Vidal, A.; Skarmeta, A.F.; Chabaa, S.; Zeroual, A. A hybrid neuro-fuzzy inference system-based algorithm for time series forecasting applied to energy consumption prediction. Appl. Energy 2020, 268, 114977.

- Walter, T.; Sohn, M.D. A regression-based approach to estimating retrofit savings using the Building Performance Database. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 996–1005.

- Zeng, A.; Liu, S.; Yu, Y. Comparative study of data driven methods in building electricity use prediction. Energy Build. 2019, 194, 289–300.

- Li, K.; Ma, Z.; Robinson, D.; Lin, W.; Li, Z. A data-driven strategy to forecast next-day electricity usage and peak electricity demand of a building portfolio using cluster analysis, Cubist regression models and Particle Swarm Optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123115.

- Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Ko, W. Day-Ahead Electric Load Forecasting for the Residential Building with a Small-Size Dataset Based on a Self-Organizing Map and a Stacking Ensemble Learning Method. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1231.

- Chakraborty, D.; Elzarka, H. Early detection of faults in HVAC systems using an XGBoost model with a dynamic threshold. Energy Build. 2019, 185, 326–344.

- Kapetanakis, D.-S.; Mangina, E.; Finn, D.P. Input variable selection for thermal load predictive models of commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 137, 13–26.

- Ribeiro, M.; Grolinger, K.; ElYamany, H.F.; Higashino, W.A.; Capretz, M.A.M. Transfer learning with seasonal and trend adjustment for cross-building energy forecasting. Energy Build. 2018, 165, 352–363.

- Deb, C.; Zhang, F.; Yang, J.; Lee, S.E.; Shah, K.W. A review on time series forecasting techniques for building energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 74, 902–924.

- Li, X.; Wen, J. System identification and data fusion for on-line adaptive energy forecasting in virtual and real commercial buildings. Energy Build. 2016, 129, 227–237.

- Chalal, M.L.; Benachir, M.; White, M.; Shrahily, R. Energy planning and forecasting approaches for supporting physical improvement strategies in the building sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 761–776.

- Wang, Z.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Building thermal load prediction through shallow machine learning and deep learning. Appl. Energy 2020, 263, 114683.

- Zhao, H.; Magoulès, F. A review on the prediction of building energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3586–3592.

- Wang, Z.; Srinivasan, R.S. A review of artificial intelligence based building energy use prediction: Contrasting the capabilities of single and ensemble prediction models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 796–808.

- Foucquier, A.; Robert, S.; Suard, F.; Stéphan, L.; Jay, A. State of the art in building modelling and energy performances prediction: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 23, 272–288.

- Bourdeau, M.; Zhai, X.Q.; Nefzaoui, E.; Guo, X.; Chatellier, P. Modeling and forecasting building energy consumption: A review of data-driven techniques. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101533.

- Lü, X.; Lu, T.; Kibert, C.J.; Viljanen, M. Modeling and forecasting energy consumption for heterogeneous buildings using a physical–statistical approach. Appl. Energy 2015, 144, 261–275.

- Kamel, E.; Sheikh, S.; Huang, X. Data-driven predictive models for residential building energy use based on the segregation of heating and cooling days. Energy 2020, 206, 118045.

- Liu, C.; Sun, B.; Zhang, C.; Li, F. A hybrid prediction model for residential electricity consumption using holt-winters and extreme learning machine. Appl. Energy 2020, 275, 115383.

- Imam, S.; Coley, D.A.; Walker, I. The building performance gap: Are modellers literate? Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2017, 38, 351–375.

- Ha, S.; Tae, S.; Kim, R. Energy Demand Forecast Models for Commercil Buildings in South Korea. Energies 2019, 12, 2313.

- Blázquez-García, A.; Conde, A.; Milo, A.; Sánchez, R.; Barrio, I. Short-term office building elevator energy consumption forecast using SARIMA. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2020, 13, 69–78.

- Oh, S.J.; Ng, K.C.; Thu, K.; Chun, W.; Chua, K.J.E. Forecasting long-term electricity demand for cooling of Singapore’s buildings incorporating an innovative air-conditioning technology. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 183–193.

- Li, X.; Wen, J.; Liu, R.; Zhou, X. Commercial building cooling energy forecasting using proactive system identification: A whole building experiment study. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2016, 22, 674–691.

- Yu, D. A two-step approach to forecasting city-wide building energy demand. Energy Build. 2018, 160, 1–9.

- Kang, M.; Bergέs, M.; Akinci, B. Forecasting Airport Building Electricity Demand on the Basis of Flight Schedule Information for Demand Response Applications. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2017, 2603, 29–38.

- Ghedamsi, R.; Settou, N.; Gouareh, A.; Khamouli, A.; Saifi, N.; Recioui, B.; Dokkar, B. Modeling and forecasting energy consumption for residential buildings in Algeria using bottom-up approach. Energy Build. 2016, 121, 309–317.

- Lee, D. Low-cost and simple short-term load forecasting for energy management systems in small and middle-sized office buildings. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2020, 014459871990096.

- Lindberg, K.B.; Bakker, S.J.; Sartori, I. Modelling electric and heat load profiles of non-residential buildings for use in long-term aggregate load forecasts. Util. Policy 2019, 58, 63–88.

- Szul, T.; Kokoszka, S. Application of Rough Set Theory (RST) to Forecast Energy Consumption in Buildings Undergoing Thermal Modernization. Energies 2020, 13, 1309.

- Raza, M.Q.; Khosravi, A. A review on artificial intelligence based load demand forecasting techniques for smart grid and buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 1352–1372.

- Wang, R.; Lu, S.; Feng, W. A novel improved model for building energy consumption prediction based on model integration. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114561.

- Yang, J.; Ning, C.; Deb, C.; Zhang, F.; Cheong, D.; Lee, S.E.; Sekhar, C.; Tham, K.W. k-Shape clustering algorithm for building energy usage patterns analysis and forecasting model accuracy improvement. Energy Build. 2017, 146, 27–37.

- Zhang, L.; Wen, J. A systematic feature selection procedure for short-term data-driven building energy forecasting model development. Energy Build. 2019, 183, 428–442.

- Ahmad, T.; Zhang, H. Novel deep supervised ML models with feature selection approach for large-scale utilities and buildings short and medium-term load requirement forecasts. Energy 2020, 209, 118477.

- Hippert, H.S.; Pedreira, C.E.; Souza, R.C. Neural networks for short-term load forecasting: A review and evaluation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2001, 16, 44–55.

- Divina, F.; García Torres, M.; Goméz Vela, F.A.; Vázquez Noguera, J.L. A Comparative Study of Time Series Forecasting Methods for Short Term Electric Energy Consumption Prediction in Smart Buildings. Energies 2019, 12, 1934.

- Ghiassi, M.; Zimbra, D.K.; Saidane, H. Medium term system load forecasting with a dynamic artificial neural network model. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2006, 76, 302–316.

- Çunkaş, M.; Altun, A.A. Long Term Electricity Demand Forecasting in Turkey Using Artificial Neural Networks. Energy Sources, Part B Econ. Planning, Policy 2010, 5, 279–289.

- Ahmad, T.; Chen, H.; Huang, R.; Yabin, G.; Wang, J.; Shair, J.; Azeem Akram, H.M.; Hassnain Mohsan, S.A.; Kazim, M. Supervised based machine learning models for short, medium and long-term energy prediction in distinct building environment. Energy 2018, 158, 17–32.

- Khwaja, A.S.; Naeem, M.; Anpalagan, A.; Venetsanopoulos, A.; Venkatesh, B. Improved short-term load forecasting using bagged neural networks. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2015, 125, 109–115.

- Taylor, J.W. Triple seasonal methods for short-term electricity demand forecasting. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 204, 139–152.

- Hernandez, L.; Baladron, C.; Aguiar, J.M.; Carro, B.; Sanchez-Esguevillas, A.J.; Lloret, J.; Massana, J. A Survey on Electric Power Demand Forecasting: Future Trends in Smart Grids, Microgrids and Smart Buildings. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2014, 16, 1460–1495.

- Amasyali, K.; El-Gohary, N.M. A review of data-driven building energy consumption prediction studies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1192–1205.

- Jia, N.X.; Yokoyama, R.; Zhou, Y.C.; Gao, Z.Y. A flexible long-term load forecasting approach based on new dynamic simulation theory—GSIM. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2001, 23, 549–556.

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, R.; Srinivasan, R.S.; Ahrentzen, S. Random Forest based hourly building energy prediction. Energy Build. 2018, 171, 11–25

- Fu, G. Deep belief network based ensemble approach for cooling load forecasting of air-conditioning system. Energy 2018, 148, 269–282.

- Gassar, A.A.A.; Cha, S.H. Energy prediction techniques for large-scale buildings towards a sustainable built environment: A review. Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110238.

- Agyeman, K.A.; Kim, G.; Jo, H.; Park, S.; Han, S. An Ensemble Stochastic Forecasting Framework for Variable Distributed Demand Loads. Energies 2020, 13, 2658.

- Luo, X.J.; Oyedele, L.O.; Ajayi, A.O.; Akinade, O.O.; Owolabi, H.A.; Ahmed, A. Feature extraction and genetic algorithm enhanced adaptive deep neural network for energy consumption prediction in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 109980.

- Zhang, L.; Alahmad, M.; Wen, J. Comparison of time-frequency-analysis techniques applied in building energy data noise cancellation for building load forecasting: A real-building case study. Energy Build. 2020, 110592.

- Spiliotis, E.; Petropoulos, F.; Kourentzes, N.; Assimakopoulos, V. Cross-temporal aggregation: Improving the forecast accuracy of hierarchical electricity consumption. Appl. Energy 2020, 261, 114339.

- Kathirgamanathan, A.; De Rosa, M.; Mangina, E.; Finn, D.P. Data-driven predictive control for unlocking building energy flexibility: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 135, 110120

- Alshibani, A. Prediction of the Energy Consumption of School Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5885.

- Dorokhova, M.; Ballif, C.; Wyrsch, N. Rule-based scheduling of air conditioning using occupancy forecasting. Energy AI 2020, 2, 100022.

- Das, A.; Annaqeeb, M.K.; Azar, E.; Novakovic, V.; Kjærgaard, M.B. Occupant-centric miscellaneous electric loads prediction in buildings using state-of-the-art deep learning methods. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 115135.