| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yoko Yamabe-Mitarai | + 3301 word(s) | 3301 | 2020-11-24 09:21:51 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -1261 word(s) | 2040 | 2020-11-26 05:23:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

With the aim to improve the strength of high-temperature shape memory alloys, multi-component alloys, including medium- and high-entropy alloys, have been investigated and proposed as new structural materials. Notably, it was discovered that the martensitic transformation temperature could be controlled through a combination of the constituent elements and alloys with high austenite finish temperatures above 500 °C. The irrecoverable strain decreased in the multi-component alloys compared with the ternary alloys. The repeated thermal cyclic test was effective toward obtaining perfect strain recoveries in multi-component alloys, which could be good candidates for high-temperature shape memory alloys.

1. Introduction

Shape recovery in shape memory alloys (SMAs) occurs during a reverse martensitic transformation from martensite to austenite phases. Thereafter, the SMA operating temperature is related to the martensitic transformation temperature (MTT). High-temperature shape memory alloys (HT-SMAs) are defined as SMAs that can recover their shapes at temperatures above 100 °C. Several applications of HT-SMAs have been proposed. For example, Ni30Pt20Ti50, whose MTTs include austenite start temperature, As: 262 °C; austenite finish temperature, Af: 275 °C; martensite start temperature, Ms: 265 °C; and martensite finish temperature, Mf: 240 °C, was applied for active clearance control actuation in the high-pressure turbine section of a turbofan engine [1]. This indicates that the design can offer a small and lightweight package without requiring motion amplifiers that cause efficiency losses and introduce an additional failure mode[1]. Another example is the helical actuators for surge-control applications in helicopter engine compressors[2]. In this application, Ni19.5Ti50.5Pd25Pt5, whose MTTs comprise As: 243 °C, Af: 259 °C, Ms: 247 °C, and Mf: 228 °C, was applied because the alloy exhibited good work capabilities, a 2.5% recoverable strain, and a work output of 9.45 J/cm3 at 400 MPa[2] . Several SMA applications, such as the active jet engine chevron, springs and wires for a general class of high-temperature actuators, oxygen mask deployment latch, SMA-activated thermal switch for lunar surface applications, variable geometry chevrons, and gas turbine variable area nozzles, have also been proposed [3]. Here, HT-SMAs, Ni19.5Ti50.5Pd25Pt5 or Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20 are used only in springs and wires for a general class of high-temperature actuator. Furthermore, NiTi-based SMAs that can actuate in the temperature range of 70–90 °C are used in other applications.

Raising MTTs is necessary for the development of HT-SMAs. In addition, improving SMA strength is also important because plastic deformation easily occurs at high temperatures, thereby resulting in incomplete shape recovery. Several studies have been conducted to increase MTTs by adding alloying elements such as Hf, Zr, Pd, Pt, and Au, to NiTi[4][5][6][7][8][9][10]. Their MTTs successfully increased by adding an alloying element, but a perfect shape recovery was not obtained. Recently, research of NiTi alloys has shifted to Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20, which is strengthened by nano-size precipitates called the “H phase” [11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. The austenite finishing temperature Af of Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20 is typically 166 °C under unloading conditions[13], but it rises to 270 °C under tensile loading conditions at 500 MPa[16] . Furthermore, ageing increased the work output due to the higher transformation strain and the work output under 500 MPa was 16.45 J/cm3 at Af of 270 °C[16] . High strength Ni-rich Ni51.2Ti28.8Hf20 was also developed and its work output was 23 J/cm3 under 1700 MPa at Af of approximately 100 °C, 27 J/cm3 under 1500 MPa at Af of approximately 220 °C, and 15 J/cm3 under 1000 MPa at As of 151 °C (Af was not clearly shown)[19]. The effect of 2000 thermal training cycles under 300 MPa of Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20 was also investigated and it was found that the stable cyclic strain recovery with the almost constant transformation strain[24]. The work output under 300 MPa was approximately 7.5 J/cm3 at Af of approximately 220 °C[24].

Another approach to increasing MTTs is using other alloys with MTTs higher than those of NiTi alloys. Therefore, TiPd, TiAu, and TiPt have been studied because they exhibit a martensitic transformation from a B2 to a B19 structure, and their MTT values are higher than 500 °C[25][26]. For example, typical martensitic twin structures were observed in TiPt, whose high potential as an HT-SMA has been established[27][28]. The first investigation on strain recovery at high temperatures was performed for TiPd[29]. A binary TiPd sample was deformed at 500 °C, and the change in its length after it was heated above the Af was investigated to measure strain recovery[29]. However, only a 10% strain was recovered owing to plastic deformation at 500 °C[29]. The effect of an alloying element on MTTs, strain recovery, as well as strength of the martensite and austenite phases in TiPd and TiPt alloys, have been investigated by my group [33-50] and are reviewed herein. In addition to the TiPd and TiPt alloys, high- and medium-entropy SMAs (HEAs or MEAs) are also appraised because HEAs and MEAs have been attracting considerable attention as new SMAs. Notably, HEAs and MEAs are multi-component equiatomic or near-equiatomic alloys, which have garnered much interest as new generation structural materials because their high-entropy effects, such as severe lattice distortion and sluggish diffusion, are expected to improve the high-temperature strength of alloys [51, 52]. As already shown, it is difficult to achieve perfect strain recovery in HT-SMAs because of the easy introduction of plastic deformation at high temperatures. Furthermore, improvement of strength of SMAs is a key issue for HT-SMAs. Application of HEAs and MEAs to HT-SMAs is expected in this area for whith results on multi-component alloys, in particularly MEAs and HEAs, are presented in this paper.

2. Strain Recovery of Multi-Component Alloys

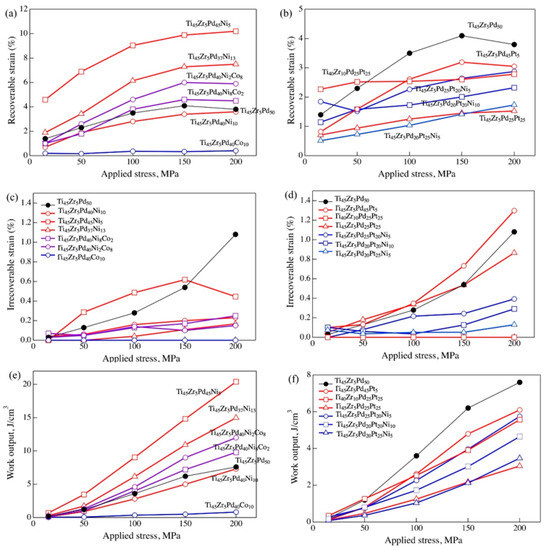

A thermal cyclic test was performed on the multi-component alloys to investigate strain recovery. Some results have already been published[30][31][32][33][34][35]. The recoverable and irrecoverable strains, as well as the work output of some of the multi-component alloys are shown in Figure 1; the TiZrPdNi and TiZrPdPt alloys are shown in Figure 1a,c,e, and in Figure 1b,d,f, respectively, while Ti45Pd50Zr5 is shown as a standard sample in all the diagrams. Furthermore, Ti45Zr5Pd45Ni5, Ti45Zr5Pd37Ni13, Ti40Zr10Pd25Pt25, and Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt20Ni5 are the original data source in this study. In Figure 1a,c,e, the concentrations of Ti and Zr were maintained at 45 and 5 at%, respectively, in TiZrPdNi, and only the concentrations of Pd and Ni were changed. Among the tested alloys in Figure 1a,c,e, TiZrPdNi alloys exhibited a relatively high recoverable strain, although the recoverable strain of Ti45Zr5Pd40Ni10[33] was similar to that of ternary Ti45Pd50Zr5. Moreover, Ni addition seems to increase the recoverable strain of Ti45Pd50Zr5. The recoverable strain of Ti45Zr5Pd40Co10 [33] was very small, thereby suggesting that Co addition drastically decreased the recovery strain. However, the recoverable strain of the multi-component alloys of TiZrPdNiCo was larger than that of Ti45Zr5Pd40Ni10[33]. This indicated that the recoverable strain was increased by the effect of the multi-component alloy, i.e., the high-entropy effect. In Figure 1c, the irrecoverable strains of most of the tested alloys were smaller than 0.2%. Only the ternary Ti45Pd50Zr5 and quaternary alloy of Ti45Zr5Pd45Ni5, which were defined as LEA, represented a large irrecoverable strain exceeding 0.2%. A decrease in the irrecoverable strain of MEAs is also considered to be consequent of the high-entropy effect. As a result of the large recoverable strain, the work output of TiZrPdNi-type multi-component alloys also becomes large, as shown in Figure 1e. The work outputs of some alloys exceeded 10 J/cm3. The repeated thermal cycling test, i.e., training was also applied for some alloys. For example, training under 300 MPa was performed for Ti45Zr5Pd40Ni10 for 100 cycles[33]. Although the transformation strain decreased, the irrecoverable strain decreased, and a perfect recovery was finally achieved during the thermal cyclic test. The final recovery strain was approximately 3.6% under 300 MPa. Thereafter, the work output was 10.8 J/cm3 at the Af of 258 °C. For Ti45Zr5Pd40Co10, training was performed under 700 MPa. After nine cycles, the irrecoverable strain disappeared, and a perfect recovery was achieved. The final recovery strain was approximately 1%, and the work output was 7 J/cm3 at the Af of 361 °C.

Figure 1. (a,b) Recoverable strain, (c,d) irrecoverable strain, and (e,f) work output obtained from strain–temperature curves of thermal cycle tests of between 15 and 200 MPa for Ti45Zr5 Pd50 [30] and multi-component alloys. (a,c,d) TiZrPdNi alloys [32][33], and (b,d,f) TiZrPdPt alloys[30][32][34].

In Figure 1b,d,f, TiZrPdPt alloys are compared. Again, the concentrations of Ti and Zr were maintained at 45 and 5 at%, respectively, in most of the alloys. Compared with the recoverable strain in TiZrPdNi alloys, as shown in Figure 1a and in TiZrPdPt alloys, as presented in Figure 1b, those of TiZrPdPt alloys were smaller than 3% and less than those of TiZrPdNi alloys. This indicates that the addition of Pt decreases the recoverable strain. The same trend can be observed in quaternary alloys by comparing Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt25 and Ti45Zr5Pd45Pt5. A small recoverable strain was achieved in the alloy with high Pt content. The effect of Zr on the recoverable strain in quaternary alloys could be understood by comparing Ti40Zr10Pd25Pt25 and Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt25, and it was found that Zr addition increased the recoverable strain. In the multi-component alloys, it was found that high Pt addition decreased recoverable strain, as shown in Figure 1b. In TiZrPdPt alloys, it was found that the irrecoverable strain decreased in the multi-component alloys including the MEAs and HEAs, except for the LEA, Ti45Zr5Pd45Pt5, as shown in Figure 1d. The irrecoverable strain of Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt25 is also small, which may be due to high MTT. The work outputs of the TiZrPdPt alloys are shown in Figure 1f; they are all between 2–6 J/cm3 and smaller than that of Ti45Pd50Zr5.

Training was performed for Ti45Zr5Pd20Pt25Ni5 and Ti45Zr5Pd20Pt20Ni10 [34], and perfect recovery was achieved during the thermal cyclic test for approximately 100 cycles under loads of 200, 300, and 400 MPa, whereby the final work outputs were approximately 3.5, 3, and 2 J/cm3, respectively, for Ti45Zr5Pd20Pt25Ni5. For Ti45Zr5Pd20Pt20Ni10, final work outputs of 3 and 1.5 J/cm3 under loads of 200 and 300 MPa were obtained, respectively. The small work output for the large applied stress represents a drastic decrease in the transformation strain. It is necessary to keep the transformation strain of the multi-component alloys during the thermal cyclic test. The thermal cyclic test is considered as a kind of thermal fatigue test and the stable cyclic strain recovery with the constant transformation strain indicates the thermal fatigue life of SMAs and stability as SMA actuators.

The strength of the austenite and martensite phases of some of the multi-component alloys are investigated, and the results are summarized in Table 1. The strength of the austenite phases in the tested alloys was between 200 and 300 MPa, and they were similar to those of the ternary alloys. This is because the MTTs of the multi-component alloys are relatively high. Therefore, it is difficult to correlate the strength and strain recovery directly. Thereafter, the temperature dependence of the strength of the martensite and austenite phases was investigated for ternary and multi-component alloys[34]. The strength of the multi-component alloys was higher in both martensite and austenite phases when compared at the same temperature. The solid-solution strengthening effect of the multi-component alloys was more evident when the strength of the austenite phase was compared at the same test temperature of 700 °C. The strength of the multi-component alloys was higher than that of the ternary alloys or LEAs.

Table 1. Strength of the martensite and austenite phases of the multi-element alloys.

| Alloy | Test Temp., °C | The Difference from Martensite Transformation Temperature, °C | Detwining Stress, MPa | 0.2% Flow Stress, MPa | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ti45Pd45Pt5Zr5 | - | Af + 30 | - | 281 | [30] |

| Ti45Pd45Pt5Zr5 | 425 | Mf − 30 | 246 | 877 | [30] |

| Ti45Pd35Pt15Zr5 | - | Af + 30 | - | 315 | [30] |

| Ti45Pd35Pt15Zr5 | 442 | Mf − 30 | 387 | 1080 | [30] |

| Ti45Pd25Pt25Zr5 | - | Af + 30 | - | 231 | [30] |

| Ti45Pd25Pt25Zr5 | 509 | Mf − 30 | 436 | 1205 | [30] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd20Ni5Pt25 | 628 | Af + 30 | - | 322 | [34] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd20Ni5Pt25 | 402 | Mf − 30 | - | 1266 | [34] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd20Ni10Pt20 | 472 | Af + 30 | - | 610 | [34] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd20Ni10Pt20 | 226 | Mf − 30 | - | 1615 | [34] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt20Au5 | 620 | Af + 30 | - | 267 | [35] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt20Au5 | 423 | Mf − 30 | - | 1169 | [35] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt20Co5 | 568 | Af + 30 | - | 269 | [35] |

| Ti45Zr5Pd25Pt20Co5 | 294 | Mf − 30 | - | 741 | [35] |

References

- DeCastro, J.A.; Melcher, K.J.; Noebe, R.D. NASA/TM-2005-213834, AIAA-2005-3988. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20050203852 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Stebner, A.; Padula, S., II; Noebe, R.; Lerch, B.; Quinn, D. Development, Characterization, and Design Considerations of Ni19.5Ti50.5Pd25Pt5 High-temperature Shape Memory Alloy Helical Actuators. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2009, 20, 2107–2126.

- Benefan, O.; Brown, J.; Calkins, F.T.; Kumar, P.; Stebner, A.P.; Turner, T.L.; Vaidyanathan, R.; Webster, J.; Young, M.L. Shape memory alloy actuator design: CASMART collaborative best practices and case studies. Int. J. Mech. Mater. Des. 2014, 10, 1–42.

- Ma, J.; Karaman, I.; Noebe, R.D. High temperature shape memory alloys. Int. Mater. Rev. 2010, 55, 257–315.

- Bigelow, G.S.; Padula, S.A., II; Garg, A.; Gaydosh, D.; Noebe, R.D. Characterization of ternary NiTiPd high-temperature shape-memory alloys under load-biased thermal cycling. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2010, 41, 3065–3079.

- “Development of a Numerical Model for High-Temperature Shape Memory Alloys” NASA Technical Reports Server, 2013. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20060028493 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Atli, K.C.; Karaman, I.; Noebe, R.D.; Garg, A.; Chumlyakov, Y.I.; Kireeva, I.V. Improvement in the Shape Memory Response of Ti50.5Ni24.5Pd25 High-Temperature Shape Memory Alloy with Scandium Microalloying. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2010, 41, 2485–2497.

- Atli, K.C.; Karaman, I.; Noebe, R.D.; Maier, H.J. Comparative analysis of the effects of severe plastic deformation and thermomechanical training on the functional stability of Ti50.5Ni24.5Pd25 high-temperature shape memory alloy. Scr. Mater. 2011, 64, 315–318.

- Atli, K.C.; Karaman, I.; Noebe, R.D. Work output of the two-way shape memory effect in Ti50.5Ni24.5Pd25 high-temperature shape memory alloy. Scr. Mater. 2011, 65, 903–906.

- Atli, K.C.; Karaman, I.; Noebe, R.D.; Garg, A.; Chumlyakov, Y.I.; Kireeva, I.V. Shape memory characteristics of Ti50.5Ni24.5Pd25Sc0.5 high-temperature shape memory alloy after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 4747–4760.

- Yang, F.; Coughlin, D.R.; Phillips, P.J.; Yang, L.; Devaraj, A.; Kovarik, L. Structure analysis of a precipitate phase in an Ni-rich high-temperature NiTiHf shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 3335–3346.

- Santamarta, R.; Arroyave, R.R.; Pons, J.; Evrigen, A.; Karaman, I.; Karacka, H.E.; Noebe, R.D. TEM study of structural and microstructural characteristics of a precipitate phase in NI-rich Ni-Ti-Hf and Ni-Ti-Zr shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 6191–6206.

- Bigelow, G.S.; Garg, A.; Padula, S.A., II; Gaydosh, D.J.; Noebe, R.D. Load-biased shape-memory and superelastic properties of a precipitation strengthened high-temperature Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20 alloy. Scr. Mater. 2011, 64, 725–728.

- Coughlin, D.R.; Phillips, P.J.; Bigelow, G.S.; Garg, A.; Noebe, R.D.; Mills, M.J. Characterization of the microstructure and mechanical properties of a 50.3Ni-29.7Ti-20Hf shape memory alloy. Scr. Mater. 2012, 67, 112–115.

- Evirgen, A.; Basner, F.; Karaman, I.; Noeve, R.D.; Pons, J.; Santamarta, R. Effect of Aging on the martensitic transformation characteristics of a Ni-rich NiTiHf high temperature shape meory alloys. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2012, 5, 1250038.

- Karaca, H.E.; Saghaian, S.M.; Ded, G.; Tobe, H.; Basaran, B.; Maier, H.J.; Noebe, R.D.; Chumlyakov, Y.I. Effects of nanoprecipitation on the shape memory and material properties of an Ni-rich NiTiHf high temperature shape memory alloy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 7422–7431.

- Benafan, O.; Garg, A.; Noebe, R.D.; Bigelow, G.S.; Padula, S.A.; Gaydosh, D.J.; Schell, N.; Mabe, J.H.; Vaidyanathan, R. Mechanical and functional behavior of Ni-rich Ni50.3Ti29.7Hf20 high temperature shape memory alloy. Intermet 2014, 50, 94–107.

- Evirgen, A.; Karaman, I.; Santamarta, R.; Pons, J.; Hayrettin, C.; Noebe, R.D. Relationship between crystallographic compatibility and thermal hysteresis in Ni-rich NiTiHf and NiTiZr high temperature shape memory alloys. Acta Mater. 2016, 121, 374–383.

- Saghaian, S.M.; Karaca, H.E.; Tobe, H.; Turabi, A.S.; Saedi, S.; Saghaian, S.E.; Chumlyakov, Y.I.; Noebe, R.D. High strength NiTiHf shape memory alloys with tailorable properties. Acta Mater. 2017, 134, 211–220.

- Amin-Ahmadi, B.; Gallmeyer, T.; Pauza, J.G.; Duerig, T.W.; Noebe, R.D.; Stebner, A.P. Effect of a pre-aging treatment on the mechanical behaviors of Ni50.3Ti49.7−xHfx(x < 9 at.%) Shape memory alloys. Scr. Mater. 2018, 147, 11–15.

- Amin-Ahmadi, B.; Pauza, J.G.; Shamimi, A.; Duerig, T.W.; Noebe, R.D.; Stebner, A.P. Coherency strains of H-phase precipitates and their influence on functional properties of nickel-titanium-hafnium shape memory alloys. Scr. Mater. 2018, 147, 83–87.

- Evirgen, A.; Pons, J.; Karaman, I.; Santamarta, R.; Noebe, R.D. H-Phase Precipitation and Martensitic Transformation in Ni-rich Ni-Ti-Hf and Ni-Ti-Zr High-Temperature Shape Memory Alloys. Shap. Mem. Superelasticity 2018, 4, 85–92.

- Amin-Ahmadi, B.; Noebe, R.D.; Stebner, A.P. Crack propagation mechanisms of an aged nickel-titanium-hafnium shape memory alloy. Scr. Mater. 2019, 159, 85–88.

- Karakoc, O.; Atli, K.C.; Evirgen, A.; Pons, J.; Santamarta, R.; Benafan, O.; Noebe, R.D.; Karaman, I. Effects of training on the thermomechanical behavior of NiTiHf and NiTiZr high temperature shape memory alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 794, 139857.

- ASM Alloy Phase Diagrams Center; Villars, P.; Okamoto, H.; Cenzual, K. (Eds.) ASM International, Materials Park, OH, 2006. Available online: http://www1.asminternational.org/AsmEnterprise/APD (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Donkersloot, H.C.; van Vocht, J.H.N. Martensitic transformations in gold-titanium, palladium-titanium and platinum-titanium alloys near the equiatomic composition. J. Less Common Met. 1970, 20, 83–91.

- Biggs, T.; Witcomb, M.J.; Cornish, L.A. Martensite-type transformations in platinum alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 273–278, 204–207.

- Biggs, T.; Corite, M.B.; Witcomb, M.J.; Cornish, L.A. Martensitic Transformations, Microstructure, and Mechanical Workability of TiPt. Metall. Trans. A 2003, 32A, 2267–2272.

- Otsuka, K.; Oda, K.; Ueno, Y.; Piao, M.; Ueki, T.; Horikawa, H. The shape memory effect in a Ti50Pd50 alloy. Scr. Met. Mater. 1993, 29, 1355–1358.

- Tasaki, W.; Shimojo, M.; Yamabe-Mitarai, Y. Thermal cyclic properties of Ti-Pd-Pt-Zr high-temperature shape memory alloys. Crystals 2019, 9, 595.

- Yamabe-Mitarai, Y.; Takebe, W.; Shimojo, M. Phase transformation and shape memory effect of Ti-Pd-Pt-Zr high-temperature shape memory alloys. Shap. Mem. Superelasticity 2017, 3, 381–391.

- Yamabe-Mitarai, Y.; Tasaki, W.; Ohl, B.; Sato, H. Effect of Ni, Co, and Pt on Phase transformation and shape recovery of TiPd high temperature shape memory alloys. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Processing & Manufacturing of Advanced Materials, Paris, France, 9–13 July 2018.

- Yamabe-Mitarai, Y.; Ohl, B.; Bogdanowicz, K.; Muszalska, E. Effect of Ni and Co on Phase Transformation and Shape Memory Effect of Ti-Pd-Zr alloys. Shap. Mem. Superelasticity 2020, 6, 170–180.

- Matsuda, H.; Sato, H.; Shimojo, M.; Yamabe-Mitarai, Y. Improvement of high-temperature shap-memory effect by multi-component alloyin for TiPd alloys. Mater. Trans. 2019, 11, 2282–2291.

- Matsuda, H.; Shimojo, M.; Murakami, H.; Yamabe-Mitarai, Y. Martensitic Transformation of High-Entropy and Medium-Entropy Shape Memory Alloys. Mater. Sci. Forum 2021, 1016, 1802–1810.