1000/1000

Hot

Most Recent

In the midst of the global 2020 COVID-19 outbreak, the advantages of online food delivery (FD) were obvious as it facilitated consumer access to prepared meals and enabled food providers to keep operating. However, online FD is not without its critics, with reports of consumer and restaurant boycotts. It is therefore time to take stock and consider the broader impacts of online FD and what they mean for the stakeholders involved. Using the three pillars of sustainability as a lens through which to consider the impacts, this review presents the most up-to-date research in this field revealing a raft of positive and negative impacts. From an economic standpoint, online FD while providing job and sale opportunities has been criticized for high commissions it charges restaurants and questionable working conditions for delivery people. From a social perspective, online FD is affecting the relationship between consumers and their food as well as influencing public health outcomes and traffic systems. Environmental impacts include the generation of worrying amounts of waste and its high carbon footprints. Stakeholders must consider how best to mitigate the negative and promote the positive impacts of online FD to ensure that it is sustainable, in every sense, moving forward.

Online to offline (O2O) is a form of e-commerce in which consumers are attracted to a product or service online and induced to complete a transaction in an offline setting. An area of O2O commerce that is expanding rapidly is the use of online food delivery (online FD) platforms. All around the world, the rise of online FD has changed the way that many consumers and food suppliers interact, and the sustainability impacts (defined by the three pillars of economic, social and environmental [1]) of this change has yet to be comprehensively assessed.

Economic growth and increasing broadband penetration are driving the global expansion of e-commerce. Consumers are increasingly using online services as their disposable income increases, electronic payments become more trustworthy, and the range of suppliers and the size of their delivery networks expand.

The e-commerce market has experienced strong growth over the past decade, as customers increasingly move online. This shift in how consumers shop has been driven by a wide range of diverse factors, some being market or country dependent, others occurring as a result of worldwide changes. These changes include: an increase in disposal income, particularly in developing nations; longer work and commuting times; increased broadband penetration and improved safety of electronic payments; a relaxing of trade barriers; an increase in the number of retailers having an online presence; and a greater awareness of e-commerce by customers [2].

The strongest growth of e-commerce over the last few years has occurred in China, where, in 2019, sales were worth US$ 1.935 trillion—an amount which was more than three times higher than that spent in the United States (US$ 586.92 billion), the second largest market. On its own, China represents 54.7% of the global e-commerce market, a share nearly twice the market share of the next five highest countries (US, UK, Japan, South Korea, Germany) combined [3]. The rise of e-commerce in the Asia-Pacific region is demonstrated in Table 1, which highlights the massive increase in the amount spent during key online shopping days between 2015 and 2019. Of particular note is the US$ 38.4 billion spent on Singles Day (11.11) in the Asia-Pacific region in 2019, an amount which is more than double the total sum of the US$9.4 billion spent on Black Friday in North America and much of Europe and the US$ 7.4 billion spent on Cyber Monday in North America. The leading e-commerce platforms worldwide differ by region and include platforms which are now household names, such as Amazon (U.S.), Alibaba (China), and Flipkart (India).

Table 1. Regional sales value of featured online shopping days from 2015–2019 [4].

| Sales volume (US$ billion) | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Friday (North America and much of Europe) | 2.7 | 3.3 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 7.4 |

| Cyber Monday (North America) | 3.1 | 3.4 | 6.6 | 7.9 | 9.4 |

| Singles Day (Asia-Pacific region) | 14.3 | 17.8 | 25.3 | 30.8 | 38.4 |

The rapid growth of e-commerce has spawned many new forms of business, such as B2B (business to business), C2C (customer to customer), B2C (business to customer), and O2O (online to offline) [5][6]. The business of O2O is a marketing method based on information and communications technology (ICT) whereby consumers place orders for goods or services online and receive the goods or services at an offline outlet [7][8].

One of the significant developments driving the O2O commerce explosion has been the proliferation of smartphones and tablets and the development of infrastructures to support payment and delivery. In 2019 there were 5.2 billion smartphone connections, and by the end of 2020, it has been predicted that half of the people in the world will have access to mobile internet services [9].

O2O services have emerged in various fields, including the purchase of diverse product and service categories, such as food, hotel rooms, real estate, or car rentals [10]. Online FD refers to the process whereby food that was ordered online is prepared and delivered to the consumer. The development of online FD has been underpinned by the development of integrated online FD platforms, such as Uber eats, Deliveroo, Swiggy, and Meituan. Online FD platforms serve a variety of functions including providing consumers with a wide variety of food choices, the taking of orders and the relaying of these order to the food producer, the monitoring of payment, the organization of the delivery of the food and the provision of tracking facilities (Figure 1) [11]. Food delivery applications, or ‘apps’, (FDA) function within the broader context of online FD as they enable the ordering of food through mobile apps [12].

Figure 1. The functions associated with online food delivery (FD) platforms. Arrows indicate movement of information or logistic; lines indicate necessary routes; dotted lines indicate optional routes.

Food delivery providers can be categorized as being either Restaurant-to-Consumer Delivery or Platform-to-Consumer Delivery operations [13]. Restaurant-to-Consumer Delivery providers make the food and deliver it, as typified by providers, such as KFC, McDonald’s, and Domino’s. The order can be made directly through the restaurant’s online platform or via a third-party platform. These third-party platforms vary from country to country, and include examples, such as Uber eats in the U.S., Eleme in China, Just Eat in UK, and Swiggy in India. Third-party platforms also provide online delivery services from partner restaurants which do not necessarily offer delivery services themselves, a process which is defined as Platform-to-Consumer Delivery.

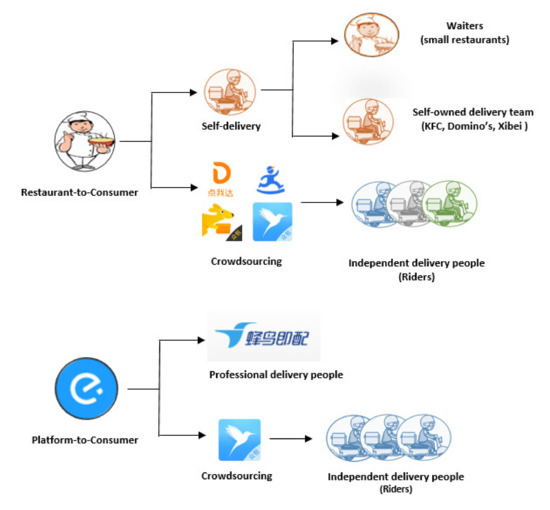

Online FD requires highly efficient and scalable real-time delivery services. Restaurants can use existing staff for self-delivery, such as the use of waiters in some small restaurants or they may use specialized delivery teams who are specifically employed and trained for this role, as is seen with some of the big restaurant brands, such as KFC, Domino’s, and Xibei. Alternatively, restaurants can employ crowdsourcing logistics, a network of delivery people (riders) who are independent contractors, a model that provides an efficient, low-cost approach to food delivery [14]. Online FD platforms can either be responsible for recruiting and training professional delivery people, or they may also resort to crowdsourcing logistics, using delivery people who are not necessarily employed by the online FD platform. Professional delivery people are usually trained, and at least part of their salary is guaranteed, while a portion is commission-based. In contrast, the independent delivery people who are frequently known as “riders” are paid on a commission (per order) basis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Online FD delivery retailers (Eleme in China, for example).

The rise of online FD is a global trend with many countries around the world having at least one major platform for food delivery (Table 2). China leads the way in market share for online FD, closely followed by the US with the developing markets of India and Brazil, showing rapid (> 9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR)) growth.

Table 2. Revenue of the Online FD segment in major countries [13].

| Country | Forecast Revenue in 2020 (in million US$) | Annual Growth Rate (CAGR 2020–2024) | Market’s Largest Delivery Segment | Volume of Market’s Largest Delivery Segment in 2020 (in million US$) | Leading Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 51,514 | 7.0% | Platform-to-Consumer | 37,708 | Meituan, Eleme |

| US | 26,527 | 5.1% | Restaurant-to-Consumer | 15,631 | Grubhub, Uber Eats, Doordash |

| India | 10,196 | 9.5% | Restaurant-to-Consumer | 5401 | Foodpanda, Swiggy, Zomato, Uber Eats |

| UK | 5988 | 6.5% | Restaurant-to-Consumer | 4115 | Just Eat, Food Hub, Deliveroo, Hungry House |

| Brazil | 3300 | 9.5% | Restaurant-to-Consumer | 2033 | iFood, HelloFood |

The online FD industry has been very proactive in the way it develops new markets and cultivates consumers’ eating habits. For example, in 2018, a promotion campaign by the India-based online FD company Foodpanda offered consumers large discounts, which resulted in Foodpanda increasing the number of users by a factor of 10 [15]. Moreover, in 2018, Eleme in China, spent three billion yuan (US$443 million) over three months in a successful marketing strategy to increase its market share to more than 50 percent of the Chinese market [16]. Despite online FD being very strong in some regions, as a whole across the world online FD is in the early stages of market development, and it will require considerable investment to fund promotions and campaigns and to provide subsidies to participating restaurants [17][18][19][20][21]. For example, a restaurant may hold a campaign on an FD platform, in which a consumer obtains ¥8 as a discount if the total amount ordered reaches ¥20. In fact, this discount may only cost the restaurant ¥2, as it will receive a ¥6 subsidy from the FD platform (the actual rules may vary from one platform to another [22]). Such an approach is beneficial for a restaurant because it will attract more consumers and orders. It is crucial for the future of online FD to cultivate consumers’ eating habits by introducing them to the choosing and purchasing of food online. By providing consumers with the option of having a meal at a cheaper price or by providing other services, such as free delivery, online FD platforms and providers are encouraging consumers to abandon cooking at home or going out to a restaurant to eat.

Worldwide online FD is becoming increasingly well accepted and embraced by young adults, and nowhere is this trend more evident than in China. A survey in 2019 of 1000 university students in Nanjing, revealed that at least 71.45% of them had used online FD for at least two years and that 85.1% of them used online FD more than once a week [23]. Online FD has been reported to be popular with Chinese university students because it saves time (50.35% of 141 students in Hebei, China), is convenient (44.35% of 124 students in Jiangxi, China), and is able to provide options that were tastier (39.52% of 124 students) or simply different from canteen meals (36.17% of 141 students) [24][25]. Of course, different populations around the world have different opportunities to purchase food online owing to cultural, technological and economic reasons and these differences can be responsible for the differing rates of uptake of online FD seen around the world. By way of comparison to China, for example, a 2019 survey of 252 Greek university students aged 18–23, reported that most of them cook at home and rarely eat out or have food delivery (45.6%), while others mostly eat at the student restaurant or cook at home (23.4%), with only 21% of the students surveyed stating that they had food delivered [26].