| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Suliman Alsagaby | + 2399 word(s) | 2399 | 2021-07-25 10:04:54 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 189 word(s) | 2588 | 2021-07-26 04:55:53 | | |

Video Upload Options

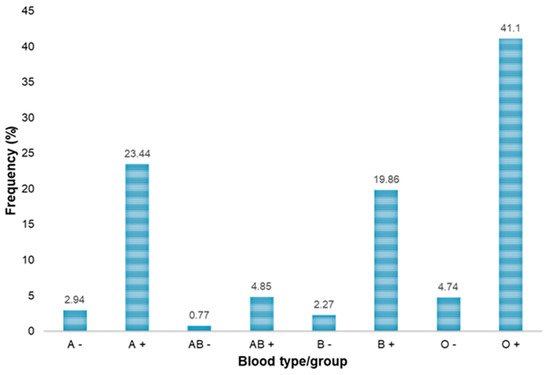

Hepatitis B and C viral infections, which are the most common cause of liver infection worldwide, are major health issues around the globe. People with chronic hepatitis infections remain at risk of liver cirrhosis and hepatic carcinoma, while also being a risk to other diseases. These infections are highly contagious in nature, and the prevention of hepatitis B and C transmission during blood transfusion is a major challenge for healthcare workers. Although epidemiological characteristics of hepatitis B and C infections in blood donors in Saudi Arabia have been previously investigated in multiple studies, due to targeted cohorts and the vast geographical distribution of Saudi Arabia, there are a lot of missing data points, which necessitates further investigations. Aim of the study: This study aimed to determine the prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viral infections among blood donors in the northern region of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Methods: To determine the given objectives, a retrospective study was performed which included data gathered from serological as well as nucleic acid test (NAT) screening of blood donors. Clinical data of 3733 blood donors were collected for a period of 2 years (from January 2019 to December 2020) at the blood bank of King Khalid General Hospital and the associated blood banks and donation camps in the region. Statistical analysis of the clinical data was performed using SPSS. Results: The blood samples of 3733 donors were analyzed to determine the seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C among the blood donors in the northern region of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Among the total of 3733 blood donors, 3645 (97.65%) were men and 88 (2.36%) were women. Most of the donors were younger than 27 years of age (n = 1494). The most frequent blood group in our study was O-positive (n = 1534), and the least frequent was AB-negative (n = 29). After statistically analyzing the clinical data, we observed that 7 (0.19%), 203 (5.44%) and 260 (6.96%) donor blood samples were positive for the HBV serological markers HBsAgs, HBsAbs and HBcAbs, respectively, and 12 (0.32%) blood samples reacted positively to anti-HCV antibodies. Moreover, 10 (0.27%) and 1 (0.027%) samples were NAT-HBV positive and NAT-HCV positive, respectively. Conclusion: In the current study, low prevalence rates of HBV and HCV were observed in the blood donors. Statistical correlations indicated that both serological tests and NATs are highly effective in screening potential blood donors for HBV and HCV, which, in turn, prevents potential transfusion-transmitted hepatitis.

1. Introduction

2. Analysis on Research Results

| Demographic Characteristics | Frequency, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Saudi nationals | 3224 (86.36) |

| Other nationalities | 509 (13.64) | |

| Total | 3733 (100) | |

| Gender | Male | 3645 (97.65) |

| Female | 88 (2.35) | |

| Total | 3733 (100) | |

| City | Majmaah | 2636 (70.6) |

| Artawiah | 229 (6.1) | |

| Riyadh | 248 (6.64) | |

| Tumair | 156 (4.17) | |

| Al-ghat | 133 (3.6) | |

| Zulfi | 83 (2.22) | |

| Other cities | 248 (6.64) | |

| Total | 3733 (100) | |

| Age | 18-27 | 1494 (40) |

| 28-37 | 1193 (32) | |

| 38-47 | 719 (19.3) | |

| 48-57 | 265 (7.1) | |

| 58-65 | 57 (1.5) | |

| >65 | 5 (0.1) | |

| Total | 3733 (100) | |

| Serological Marker/Screening Test | Test Result | Number of Donor Samples | Total Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBsAg | Negative | 3726 | 99.81% |

| Positive | 7 (7 Male; 0 Female) | 0.19% | |

| HBsAb | Negative | 3530 | 94.56% |

| Positive | 203 (198 Male; 5 Female) | 5.44% | |

| HBcAb | Negative | 3473 | 93.04% |

| Positive | 260 (255 Male; 5 Female) | 6.96% | |

| Anti-HCV | Negative | 3721 | 99.68% |

| Positive | 12 (12 Male; 0 Female) | 0.32% |

| NAT Screening Tests | Test Result | Number of Donor Samples | Total Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAT-HBV | Negative | 3723 | 99.73 |

| Positive | 10 (9 Male; 1 Female) | 0.27 | |

| NAT-HCV | Negative | 3732 | 99.97 |

| Positive | 1 Male only | 0.027 |

| Age Groups (in Years) | Blood Donors | HBsAb-Positive, n (%) |

HBsAg-Positive, n (%) |

HBcAb-Positive, n (%) |

Anti-HCV Positive, n (%) |

NAT-HBV Positive, n (%) |

NAT-HCV Positive, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–27 | 1494 | 28 (1.87) | 2 (0.13) | 53 (3.55) | 1 (0.07) | 1 (0.07) | 1 (0.07) |

| 28–37 | 1193 | 56 (4.69) | 2 (0.17) | 73 (6.12) | 3 (0.25) | 3 (0.25) | 0 (0.00) |

| 38–47 | 719 | 66 (9.18) | 2 (0.28) | 75 (10.43) | 4 (0.56) | 3 (0.42) | 0 (0.00) |

| 48–57 | 265 | 37 (13.96) | 1 (0.38) | 44 (16.60) | 4 (1.51) | 2 (0.75) | 0 (0.00) |

| 58–65 | 57 | 16 (28.07) | 0 (0.00) | 15 (26.32) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.17) | 0 (0.00) |

| >65 | 5 | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| Total | 3733 | 203 (5.44) | 7 (0.19) | 260 (6.96) | 12 (0.32) | 10 (0.27) | 1 (0.03) |

| ABO/Rh Blood Groups | Blood Donors | HBsAb-Positive, n (%) |

HBsAg-Positive, n (%) |

HBcAb-Positive, n (%) |

Anti-HCV Positive, n (%) |

NAT-HBV Positive, n (%) |

NAT-HCV Positive, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A− | 110 | 3 (2.73) | 0 (0.00) | 3 (2.73) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| A+ | 875 | 49 (5.60) | 0 (0.00) | 63 (7.20) | 2 (0.23) | 1 (0.11) | 0 (0.00) |

| B− | 85 | 1 (1.18) | 1 (1.18) | 5 (5.88) | 1 (1.18) | 1 (1.18) | 0 (0.00) |

| B+ | 742 | 40 (5.39) | 3 (0.40) | 54 (7.28) | 5 (0.67) | 5 (0.67) | 0 (0.00) |

| AB− | 29 | 3 (10.34) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (13.79) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| AB+ | 181 | 11 (6.08) | 0 (0.00) | 13 (7.18) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| O− | 177 | 10 (5.65) | 0 (0.00) | 16 (9.04) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) |

| O+ | 1534 | 86 (5.61) | 3 (0.19) | 102 (6.65) | 4 (0.26) | 3 (0.20) | 1 (0.06) |

| Total | 3733 | 203 (5.44) | 7 (0.19) | 260 (6.96) | 12 (0.32) | 10 (0.27) | 1 (0.027) |

| Parameters | NAT-HBV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Negative Units | Percentage | Number of Positive Units | Percentage | p-Value | Kappa Value | ||

| HBsAg | Negative | 3720 | 99.65% | 6 | 0.16% | <0.001 | 0.469 |

| Positive | 3 | 0.08% | 4 | 0.11% | |||

| HBcAbs | Negative | 3468 | 92.9% | 5 | 0.13% | <0.001 | 0.32 |

| Positive | 255 | 6.84% | 5 | 0.13% | |||

| HBsAbs | Negative | 3528 | 94.5% | 2 | 0.06% | <0.001 | 0.07 |

| Positive | 195 | 5.23% | 8 | 0.21% | |||

| Parameters | NAT-HCV | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Negative Units | Percentage | Number of Positive Units | Percentage | p Value | Kappa Value | ||

| Anti-HCV | Negative | 3721 | 99.67% | 0 | 0% | <0.001 | 0.15 |

| Positive | 11 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.03% | |||

3. Current Insights

References

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 1 April 2021).

- Mehta, P.; Reddivari, A.K.R. Hepatitis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021.

- Bréchot, C. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus—Related hepatocellular carcinoma: Old and new paradigms. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, S56–S61.

- Masur, H.; Brooks, J.T.; Benson, C.A.; Holmes, K.K.; Pau, A.K.; Kaplan, J.E. Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents: Updated Guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, and HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 58, 1308–1311.

- Moradpour, D.; Penin, F.; Rice, C.M. Replication of hepatitis C virus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 453–463.

- Lerat, H.; Rumin, S.; Habersetzer, F.; Berby, F.; Trabaud, M.A.; Trépo, C.; Inchauspé, G. In vivo tropism of hepatitis C virus genomic sequenc-es in hematopoietic cells: Influence of viral load, viral genotype, and cell phenotype. Blood 1998, 91, 3841–3849.

- Karnsakul, W.; Schwarz, K.B. Hepatitis B and C. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 64, 641–658.

- Busch, M.P. Should HBV DNA NAT replace HBsAg and/or anti-HBc screening of blood donors? Transfus. Clin. Biol. 2004, 11, 26–32.

- Jefferies, M.; Rauff, B.; Rashid, H.; Lam, T.; Rafiq, S. Update on global epidemiology of viral hepatitis and preventive strategies. World J. Clin. Cases 2018, 6, 589–599.

- Wiktor, S.Z.; Hutin, Y.J.-F. The global burden of viral hepatitis: Better estimates to guide hepatitis elimination efforts. Lancet 2016, 388, 1030–1031.

- Abdella, Y.; Riedner, G.; Hajjeh, R.; Sibinga, C.T.S. Blood transfusion and hepatitis: What does it take to prevent new infections? East. Mediterr. Health J. 2018, 24, 595–597.

- Sanai, F.M.; Aljumah, A.A.; Babatin, M.; Hashim, A.; Abaalkhail, F.; Bassil, N.; Safwat, M. Hepatitis B care pathway in Saudi Arabia: Current situation, gaps and actions. Saudi J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 73–80.

- Al-Raddadi, R.M.; Dashash, N.A.; Alghamdi, H.A.; Alzahrani, H.S.; Alsahafi, A.J.; Algarni, A.M.; Alraddadi, Z.M.; Alghamdi, M.M.; Hakim, R.F.; Al-Zalabani, A.H. Prevalence and predictors of hepatitis B in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia: A population-based seroprevalence study. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2016, 10, 1116–1123.

- Abdo, A.A.; Sanai, F.M.; Al-Faleh, F.Z. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Saudi Arabia: Are we off the hook? Saudi J. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Saudi Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2012, 18, 349–357.

- AlFaleh, F.; AlShehri, S.; Alansari, S.; AlJeffri, M.; Almazrou, Y.; Shaffi, A.; Abdo, A.A. Long-term protection of hepatitis B vaccine 18 years after vaccination. J. Infect. 2008, 57, 404–409.

- Hoogerwerf, M.D.; Veldhuizen, I.J.; De Kort, W.L.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; Sluiter, J.K. Factors associated with psychological and physiological stress reactions to blood donation: A systematic review of the literature. High Speed Blood Transfus. Equip. 2015, 13, 354–362.

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282.

- Prati, D. Transmission of hepatitis C virus by blood transfusions and other medical procedures: A global review. J. Hepatol. 2006, 45, 607–616.

- Ali, N. Understanding Hepatitis: An Introduction for Patients and Caregivers; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018.

- Alaidarous, M.; Choudhary, R.K.; Waly, M.I.; Mir, S.; Bin Dukhyil, A.; Banawas, S.S.; Alshehri, B.M. The prevalence of transfusion-transmitted infections and nucleic acid testing among blood donors in Majmaah, Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 702–706.

- Bashwari, L.A.; Al-Mulhim, A.A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Ahmed, M.A. Frequency of ABO blood groups in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2001, 22, 1008–1012.

- Vučetić, D.; Jovičić, M.; Maslovarić, I.; Bogdanović, S.; Antić, A.; Stanojković, Z.; Filimonović, G.; Ilić, V. Transfusion- transmissible infections among Serbian blood donors: Declining trends over the period 2005–2017. Blood Transfus. 2019, 17, 336–346.

- Okoroiwu, H.U.; Okafor, I.M.; Asemota, E.A.; Okpokam, D.C. Seroprevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections (HBV, HCV, syphilis and HIV) among prospective blood donors in a tertiary health care facility in Calabar, Nigeria; an eleven years evaluation. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 645.

- Abate, M.; Wolde, T. Seroprevalence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Hepatitis B Virus, Hepatitis C Virus, and Syphilis among Blood Donors at Jigjiga Blood Bank, Eastern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2016, 26, 153–160.

- El Beltagy, K.E.; Al Balawi, I.A.; Almuneef, M.; Memish, Z.A. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus markers among blood donors in a ter-tiary hospital in Tabuk, northwestern Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 12, 495–499.

- Ayoola, A.E.; Tobaigy, M.S.; Gadour, M.O.; Ahmad, B.S.; Hamza, M.K.; Ageel, A.M. The decline of hepatitis B viral infection in South-Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24, 991–995.

- El-Hazmi, M.M. Prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV-1, 2 and HTLV-I/II infections among blood donors in a teaching hospital in the Central region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2004, 25, 26–33.

- Sallam, T.A.; El-Bingawi, H.M.; Alzahrani, K.I.; Alzahrani, B.H.; Alzahrani, A.A. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C viral in-fections and impact of control program among blood donors in Al-Baha region, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2020, 9, 56–60.

- Al Majid, F. Prevalence of transfusion-transmissible infections among blood donors in Riyadh: A tertiary care hospital-based experience. J. Nat. Sci. Med. 2020, 3, 247–251.

- Al-Faleh, F.Z.; Al-Jeffri, M.; Ramia, S.; Al-Rashed, R.; Arif, M.; Rezeig, M.; Al-Toraif, I.; Bakhsh, M.; Mishkkhas, A.; Makki, O.; et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in Saudi children 8 years after a mass hepatitis B vaccination programme. J. Infect. 1999, 38, 167–170.

- Bashawri, L.A.M.; Fawaz, N.A.; Ahmad, M.S.; Qadi, A.A.; Almawi, W.Y. Prevalence of seromarkers of HBV and HCV among blood donors in eastern Saudi Arabia, 1998–2001. Clin. Lab. Hematol. 2004, 26, 225–228.

- Mehdi, S.R.; Pophali, A.; Al-Abdul Rahim, K.A. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C and blood donors. Saudi Med. J. 2000, 21, 942–944.

- Madani, T. Hepatitis C virus infections reported in Saudi Arabia over 11 years of surveillance. Ann. Saudi Med. 2007, 27, 191.

- Shobokshi, O.A.; Serebour, F.E.; Al-Drees, A.Z.; Mitwalli, A.H.; Qahtani, A.; Skakni, L.I. Hepatitis C virus seroprevalence rate among Saudis. Saudi Med. J. 2003, 24 (Suppl. S2), S81–S86.