| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mohammad Sultan Khuroo | + 2194 word(s) | 2194 | 2021-07-13 08:02:41 | | | |

| 2 | Mohammad Sultan Khuroo | Meta information modification | 2194 | 2021-07-13 14:39:06 | | | | |

| 3 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2194 | 2021-07-14 03:30:46 | | | | |

| 4 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2194 | 2021-10-12 06:06:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

The adverse relationship between viral hepatitis and pregnancy in developing countries had been interpreted as a reflection of retrospectively biased hospital-based data collection by the West. However, the discovery of hepatitis E virus (HEV) as the etiological agent of an epidemic of non-A, non-B hepatitis in Kashmir, and the documenting of the increased incidence and severity of hepatitis E in pregnancy via a house-to-house survey, unmasked this unholy alliance. The pathogenesis of the association is complex and several mechanisms are under intense studies. Management is multidisciplinary and needs a close watch for the development and management of acute liver failure. The development of vaccine is seen as a breakthrough in the control of hepatitis E.

1. Historical Background

2. Epidemic Hepatitis E and Pregnancy

3. HEV-ALF and Pregnancy

Several large series of ALF and its relationship with pregnancy have been reported from India. HEV was the cause of ALF in 47 of the 49 pregnant women as against 14 of the 34 nonpregnant women of childbearing age. HEV was the etiological cause in 342 patients, while 651 patients had non-HEV etiology [80]. HEV was the cause of ALF in 145 of the 244 pregnant women, 100 of the 329 nonpregnant women, and 97 of the 420 men.

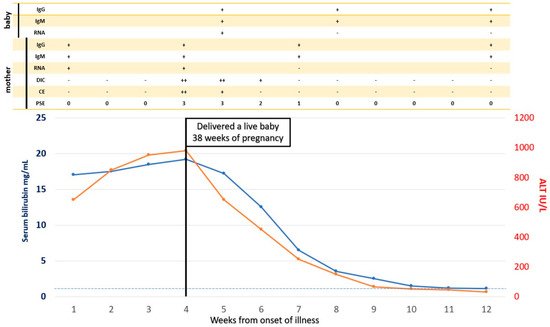

HEV-ALF in pregnant women starts with prodrome followed by other features of acute viral hepatitis [11]. However, a rapidly evolving devastating illness develops within a short pre-encephalopathy period (5.8 ± 5.3 days), characterized by encephalopathy, cerebral edema with features of cerebellar coning, coagulopathy, and upper GI bleed [81][82][83]. In addition, the occurrence of “Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)” is a distinctive feature of HEV-ALF during pregnancy [84], resembling a Schwartzmann phenomenon.

The authors compared the mortality rates in 249 pregnant women, 341 non-pregnant women, and 425 men, 15 to 45 years of age. A prospective study on 180 pregnant women with ALF revealed 79 with HEV-ALF and 101 with non-HEV-ALF [81]. Factors predictive of poor prognosis included non-HEV etiology, prothrombin time > 30 s, grade of coma > 2, and age > 40 years and did not include pregnancy per se or duration of pregnancy. The fact that pregnant women acquired ALF more often did not mean that such patients will have higher mortality [85].

4. Management

5. Vaccination

References

- Teo, C.G. Fatal outbreaks of jaundice in pregnancy and the epidemic history of hepatitis E. Epidemiol. Infect. 2012, 140, 767–787.

- Saint-Vel, O. Note on a form of severe jaundice in pregnant women. Gazette des Hôpitaux Civils et Militaires 1862, 65, 538–539. (In French)

- Decaisne, E. An epidemic of simple jaundice observed in Paris and in the vicinity. Gazette Hebdomadaire de Me´decine et de Chirurgie 1872, 19, 44. (In French)

- Khuroo, M.S.; Sofi, A.A. The Discovery of Hepatitis Viruses: Agents and Disease. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 391–401.

- Arankalle, V.A.; Chadha, M.S.; Tsarev, S.A.; Emerson, S.U.; Risbud, A.R.; Banerjee, K.; Purcell, R.H. Seroepidemiology of water-borne hepatitis in India and evidence for a third enterically-transmitted hepatitis agent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 3428–3432.

- Gupta, N.; Sarangi, A.N.; Dadhich, S.; Dixit, V.K.; Chetri, K.; Goel, A.; Aggarwal, R. Acute hepatitis E in India appears to be caused exclusively by genotype 1 hepatitis E virus. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 37, 44–49.

- Khuroo, M.S. Study of an epidemic of non-A, non-B hepatitis. Possibility of another human hepatitis virus distinct from post-transfusion non-A, non-B type. Am. J. Med. 1980, 68, 818–824.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Teli, M.R.; Skidmore, S.; Sofi, M.A.; Khuroo, M.I. Incidence and severity of viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Am. J. Med. 1981, 70, 252–255.

- Kamili, S.; Guides, S.; Khuroo, M.S.; Jameel, S.; Salahuddin, M. Hepatitis E: Studies on Transmission, Etiological Agent and Seroepidemiology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, India, 1994.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Khuroo, M.S.; Khuroo, N.S. Transmission of Hepatitis E Virus in Developing Countries. Viruses 2016, 8, 253.

- Khuroo, M.S. Hepatitis E: The enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 1991, 10, 96–100.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Khuroo, M.S. Seroepidemiology of a second epidemic of hepatitis E in a population that had recorded first epidemic 30 years before and has been under surveillance since then. Hepatol. Int. 2010, 4, 494–499.

- Jameel, S.; Durgapal, H.; Habibullah, C.M.; Khuroo, M.S.; Panda, S.K. Enteric non-A, non-B hepatitis: Epidemics, animal transmission, and hepatitis E virus detection by the polymerase chain reaction. J. Med. Virol. 1992, 37, 263–270.

- Panda, S.K.; Nanda, S.K.; Zafrullah, M.; Ansari, I.H.; Ozdener, M.H.; Jameel, S. An Indian strain of hepatitis E virus (HEV): Cloning, sequence, and expression of structural region and antibody responses in sera from individuals from an area of high-level HEV endemicity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 33, 2653–2659.

- Viswanathan, R. Infectious hepatitis in Delhi (1955–1956): A critical study—Epidemiology. Indian J. Med. Res. 1957, 45, 71–76.

- Wong, D.C.; Purcell, R.H.; Sreenivasan, M.A.; Prasad, S.R.; Pavri, K.M. Epidemic and endemic hepatitis in India: Evidence for a non-A, non-B hepatitis virus aetiology. Lancet 1980, 2, 876–879.

- Naik, S.R.; Aggarwal, R.; Salunke, P.N.; Mehrotra, N.N. A large waterborne viral hepatitis E epidemic in Kanpur, India. Bull. World Health Organ. 1992, 70, 597–604.

- Tandon, B.N.; Joshi, Y.K.; Jawn, S.J. An epidemic of non-A non-B hepatitis in north India. Indian J. Med. Res. 1982, 75, 739–744.

- Sreenivasan, M.A.; Sehgal, A.; Prasad, S.R.; Dhorje, S. A sero-epidemiologic study of a water-borne epidemic of viral hepatitis in Kolhapur City, India. J. Hyg. 1984, 93, 113–122.

- Chakraborty, S.; Dutta, M.; Pasha, S.T.; Kumar, S. Observations on outbreaks of viral hepatitis in Vidisha and Rewa district of Madhya Pradesh, 1980. J. Commun. Dis. 1983, 15, 242–248.

- Panda, S.K.; Datta, R.; Kaur, J.; Zuckerman, A.J.; Nayak, N.C. Enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis: Recovery of virus-like particles from an epidemic in south Delhi and transmission studies in rhesus monkeys. Hepatology 1989, 10, 466–472.

- Sreenivasan, M.A.; Banerjee, K.; Pandya, P.G.; Kotak, R.R.; Pandya, P.M.; Desai, N.J.; Vaghela, L.H. Epidemiological investigations of an outbreak of infectious hepatitis in Ahmedabad city during 1975-76. Indian J. Med. Res. 1978, 67, 197–206.

- Rab, M.A.; Bile, M.K.; Mubarik, M.M.; Asghar, H.; Sami, Z.; Siddiqi, S.; Dil, A.S.; Barzgar, M.A.; Chaudhry, M.A.; Burney, M.I. Water-borne hepatitis E virus epidemic in Islamabad, Pakistan: A common source outbreak traced to the malfunction of a modern water treatment plant. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997, 57, 151–157.

- Tsarev, S.A.; Emerson, S.U.; Reyes, G.R.; Tsareva, T.S.; Legters, L.J.; Malik, I.A.; Iqbal, M.; Purcell, R.H. Characterization of a prototype strain of hepatitis E virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 559–563.

- He, J. Molecular detection and sequence analysis of a new hepatitis E virus isolate from Pakistan. J. Viral Hepat. 2006, 13, 840–844.

- van Cuyck-Gandre, H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Tsarev, S.A.; Warren, R.L.; Caudill, J.D.; Snellings, N.J.; Begot, L.; Innis, B.L.; Longer, C.F. Short report: Phylogenetically distinct hepatitis E viruses in Pakistan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000, 62, 187–189.

- Tam, A.W.; Smith, M.M.; Guerra, M.E.; Huang, C.C.; Bradley, D.W.; Fry, K.E.; Reyes, G.R. Hepatitis E virus (HEV): Molecular cloning and sequencing of the full-length viral genome. Virology 1991, 185, 120–131.

- Hla, M.; Myint Myint, S.; Tun, K.; Thein-Maung, M.; Khin Maung, T. A clinical and epidemiological study of an epidemic of non-A non-B hepatitis in Rangoon. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 34, 1183–1189.

- Kane, M.A.; Bradley, D.W.; Shrestha, S.M.; Maynard, J.E.; Cook, E.H.; Mishra, R.P.; Joshi, D.D. Epidemic non-A, non-B hepatitis in Nepal. Recovery of a possible etiologic agent and transmission studies in marmosets. JAMA 1984, 252, 3140–3145.

- Gouvea, V.; Snellings, N.; Popek, M.J.; Longer, C.F.; Innis, B.L. Hepatitis E virus: Complete genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of a Nepali isolate. Virus Res. 1998, 57, 21–26.

- Shrestha, S.M. Hepatitis E in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. KUMJ 2006, 4, 530–544.

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh. Outbreak of hepatitis E in a low income urban community in Bangladesh. Health Sci. Bull. 2009, 7, 14–20.

- Sugitani, M.; Tamura, A.; Shimizu, Y.K.; Sheikh, A.; Kinukawa, N.; Shimizu, K.; Moriyama, M.; Komiyama, K.; Li, T.C.; Takeda, N.; et al. Detection of hepatitis E virus RNA and genotype in Bangladesh. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 599–604.

- Haque, F.; Banu, S.S.; Ara, K.; Chowdhury, I.A.; Chowdhury, S.A.; Kamili, S.; Rahman, M.; Luby, S.P. An outbreak of hepatitis E in an urban area of Bangladesh. J. Viral Hepat. 2015, 22, 948–956.

- Baki, A.A.; Haque, W.; Giti, S.; Khan, A.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Jubaida, N.; Rahman, M. Hepatitis E virus genotype 1f outbreak in Bangladesh, 2018. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 37, 35–37.

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh. Hepatitis E outbreak in Rajshahi City Corporation. Health Sci. Bull. 2010, 8, 12–18.

- Albetkova, A.; Drobeniuc, J.; Yashina, T.; Musabaev, E.; Robertson, B.; Nainan, O.; Favorov, M. Characterization of hepatitis E virus from outbreak and sporadic cases in Turkmenistan. J. Med. Virol. 2007, 79, 1696–1702.

- Shakhgil’dian, I.V.; Khukhlovich, P.A.; Kuzin, S.N.; Favorov, M.O.; Nedachin, A.E. Epidemiological characteristics of non-A, non-B viral hepatitis with a fecal-oral transmission mechanism. Vopr. Virusol. 1986, 31, 175–179.

- Sharapov, M.B.; Favorov, M.O.; Yashina, T.L.; Brown, M.S.; Onischenko, G.G.; Margolis, H.S.; Chorba, T.L. Acute viral hepatitis morbidity and mortality associated with hepatitis E virus infection: Uzbekistan surveillance data. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 35.

- Chatterjee, R.; Tsarev, S.; Pillot, J.; Coursaget, P.; Emerson, S.U.; Purcell, R.H. African strains of hepatitis E virus that are distinct from Asian strains. J. Med. Virol. 1997, 53, 139–144.

- Rafiev Kh, K. Viral hepatitis E: Its epidemiological characteristics in the Republic of Tajikistan. Zh Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1999, 4, 26–29.

- Alatortseva, G.I.; Lukhverchik, L.N.; Nesterenko, L.N.; Dotsenko, V.V.; Amiantova, I.I.; Mikhailov, M.I.; Kyuregian, K.K.; Malinnikova, E.Y.; Nurmatov, Z.S.; Nurmatov, A.Z.; et al. The estimation of the hepatitis E proportion in the etiological structure of acute viral hepatitis in certain regions of of Kyrgyzstan. Klin. Lab. Diagn. 2019, 64, 740–746.

- Cao, X.-Y.; Ma, X.-Z.; Liu, Y.-Z.; Jin, X.-M.; Gao, Q.; Dong, H.-J.; Zhuang, H.; Liu, C.-B.; Wang, G.-M. Epidemiological and etiological studies on enterically transmitted non-A non-B hepatitis in the south part of Xinjiang. Chin. J. Exp. Clin. Virol. 1989, 3, 1–10. (In Chinese)

- Aye, T.T.; Uchida, T.; Ma, X.Z.; Iida, F.; Shikata, T.; Zhuang, H.; Win, K.M. Complete nucleotide sequence of a hepatitis E virus isolated from the Xinjiang epidemic (1986–1988) of China. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992, 20, 3512.

- Corwin, A.; Jarot, K.; Lubis, I.; Nasution, K.; Suparmawo, S.; Sumardiati, A.; Widodo, S.; Nazir, S.; Orndorff, G.; Choi, Y.; et al. Two years’ investigation of epidemic hepatitis E virus transmission in West Kalimantan (Borneo), Indonesia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1995, 89, 262–265.

- Corwin, A.L.; Khiem, H.B.; Clayson, E.T.; Pham, K.S.; Vo, T.T.; Vu, T.Y.; Cao, T.T.; Vaughn, D.; Merven, J.; Richie, T.L.; et al. A waterborne outbreak of hepatitis E virus transmission in southwestern Vietnam. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996, 54, 559–562.

- Kim, J.H.; Nelson, K.E.; Panzner, U.; Kasture, Y.; Labrique, A.B.; Wierzba, T.F. A systematic review of the epidemiology of hepatitis E virus in Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 308.

- Bile, K.; Isse, A.; Mohamud, O.; Allebeck, P.; Nilsson, L.; Norder, H.; Mushahwar, I.K.; Magnius, L.O. Contrasting roles of rivers and wells as sources of drinking water on attack and fatality rates in a hepatitis E epidemic in Somalia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1994, 51, 466–474.

- van Cuyck-Gandre, H.; Zhang, H.Y.; Tsarev, S.A.; Clements, N.J.; Cohen, S.J.; Caudill, J.D.; Buisson, Y.; Coursaget, P.; Warren, R.L.; Longer, C.F. Characterization of hepatitis E virus (HEV) from Algeria and Chad by partial genome sequence. J. Med. Virol. 1997, 53, 340–347.

- Belabbes, E.H.; Bouguermouh, A.; Benatallah, A.; Illoul, G. Epidemic non-A, non-B viral hepatitis in Algeria: Strong evidence for its spreading by water. J. Med. Virol. 1985, 16, 257–263.

- van Cuyck, H.; Juge, F.; Roques, P. Phylogenetic analysis of the first complete hepatitis E virus (HEV) genome from Africa. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2003, 39, 133–139.

- Rioche, M.; Dubreuil, P.; Kouassi-Samgare, A.; Akran, V.; Nordmann, P.; Pillot, J. Incidence of sporadic hepatitis E in Ivory Coast based on still problematic serology. Bull. World Health Organ. 1997, 75, 349–354.

- Byskov, J. An outbreak of suspected water-borne epidemic non-A non-B hepatitis in northern Botswana with a high prevalence of hepatitis B carriers and hepatitis delta markers among patients. Trans. R. Soc. Med. Hyg. 1989, 83, 110–116.

- Coursaget, P.; Buisson, Y.; Enogat, N.; Bercion, R.; Baudet, J.M.; Delmaire, P.; Prigent, D.; Desramé, J. Outbreak of enterically-transmitted hepatitis due to hepatitis A and hepatitis E viruses. J. Hepatol. 1998, 28, 745–750.

- Goumba, A.I.; Konamna, X.; Komas, N.P. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of a hepatitis E outbreak in Bangui, Central African Republic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 93.

- Mushahwar, I.K.; Dawson, G.J.; Bile, K.M.; Magnius, L.O. Serological studies of an enterically transmitted non-A, non-B hepatitis in Somalia. J. Med. Virol. 1993, 40, 218–221.

- Ahmed, J.A.; Moturi, E.; Spiegel, P.; Schilperoord, M.; Burton, W.; Kassim, N.H.; Mohamed, A.; Ochieng, M.; Nderitu, L.; Navarro-Colorado, C.; et al. Hepatitis E outbreak, Dadaab refugee camp, Kenya, 2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1010–1012.

- Mast, E. Hepatitis E among refugees in Kenya: Minimal apparent person-to-person tranmission, evidance for age-dependant disease expression, and new serological assays. In Viral Hepatitis and Liver Disease; Kishioka, K., Suzuki, H., Mishior, S., Oda, T., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 1994; pp. 375–378.

- Boccia, D.; Guthmann, J.P.; Klovstad, H.; Hamid, N.; Tatay, M.; Ciglenecki, I.; Nizou, J.Y.; Nicand, E.; Guerin, P.J. High mortality associated with an outbreak of hepatitis E among displaced persons in Darfur, Sudan. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 1679–1684.

- Elduma, A.H.; Zein, M.M.; Karlsson, M.; Elkhidir, I.M.; Norder, H. A Single Lineage of Hepatitis E Virus Causes Both Outbreaks and Sporadic Hepatitis in Sudan. Viruses 2016, 8, 273.

- Gerbi, G.B.; Williams, R.; Bakamutumaho, B.; Liu, S.; Downing, R.; Drobeniuc, J.; Kamili, S.; Xu, F.; Holmberg, S.D.; Teshale, E.H. Hepatitis E as a cause of acute jaundice syndrome in northern Uganda, 2010–2012. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 92, 411–414.

- Howard, C.M.; Handzel, T.; Hill, V.R.; Grytdal, S.P.; Blanton, C.; Kamili, S.; Drobeniuc, J.; Hu, D.; Teshale, E. Novel risk factors associated with hepatitis E virus infection in a large outbreak in northern Uganda: Results from a case-control study and environmental analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2010, 83, 1170–1173.

- Huang, C.C.; Nguyen, D.; Fernandez, J.; Yun, K.Y.; Fry, K.E.; Bradley, D.W.; Tam, A.W.; Reyes, G.R. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the Mexico isolate of hepatitis E virus (HEV). Virology 1992, 191, 550–558.

- Maila, H.T.; Bowyer, S.M.; Swanepoel, R. Identification of a new strain of hepatitis E virus from an outbreak in Namibia in 1995. J. Gen. Virol. 2004, 85, 89–95.

- Bustamante, N.D.; Matyenyika, S.R.; Miller, L.A.; N’Gawara, M.N. Notes from the Field: Nationwide Hepatitis E Outbreak Concentrated in Informal Settlements—Namibia, 2017–2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 355–357.

- Isaacson, M.; Frean, J.; He, J.; Seriwatana, J.; Innis, B.L. An outbreak of hepatitis E in Northern Namibia, 1983. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2000, 62, 619–625.

- He, J.; Binn, L.N.; Tsarev, S.A.; Hayes, C.G.; Frean, J.A.; Isaacson, M.; Innis, B.L. Molecular characterization of a hepatitis E virus isolate from Namibia. J. Biomed. Sci. 2000, 7, 334–338.

- Wang, B.; Akanbi, O.A.; Harms, D.; Adesina, O.; Osundare, F.A.; Naidoo, D.; Deveaux, I.; Ogundiran, O.; Ugochukwu, U.; Mba, N.; et al. A new hepatitis E virus genotype 2 strain identified from an outbreak in Nigeria, 2017. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 163.

- World-Health-Organization. Acute hepatitis E—Nigeria: Disease Outbreak News 2017. Available online: (accessed on 28 April 2021).

- Escriba, J.M.; Nakoune, E.; Recio, C.; Massamba, P.M.; Matsika-Claquin, M.D.; Goumba, C.; Rose, A.M.; Nicand, E.; Garcia, E.; Leklegban, C.; et al. Hepatitis E, Central African Republic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 681–683.

- Nicand, E.; Armstrong, G.L.; Enouf, V.; Guthmann, J.P.; Guerin, J.P.; Caron, M.; Nizou, J.Y.; Andraghetti, R. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis E virus in Darfur, Sudan, and neighboring Chad. J. Med. Virol. 2005, 77, 519–521.

- Spina, A.; Lenglet, A.; Beversluis, D.; de Jong, M.; Vernier, L.; Spencer, C.; Andayi, F.; Kamau, C.; Vollmer, S.; Hogema, B.; et al. A large outbreak of Hepatitis E virus genotype 1 infection in an urban setting in Chad likely linked to household level transmission factors, 2016–2017. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188240.

- Anty, R.; Ollier, L.; Peron, J.M.; Nicand, E.; Cannavo, I.; Bongain, A.; Giordanengo, V.; Tran, A. First case report of an acute genotype 3 hepatitis E infected pregnant woman living in South-Eastern France. J. Clin. Virol. 2012, 54, 76–78.

- Tabatabai, J.; Wenzel, J.J.; Soboletzki, M.; Flux, C.; Navid, M.H.; Schnitzler, P. First case report of an acute hepatitis E subgenotype 3c infection during pregnancy in Germany. J. Clin. Virol. 2014, 61, 170–172.

- Said, B.; Ijaz, S.; Kafatos, G.; Booth, L.; Thomas, H.L.; Walsh, A.; Ramsay, M.; Morgan, D.; Hepatitis, E.I.I.T. Hepatitis E outbreak on cruise ship. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1738–1744.

- Clemente-Casares, P.; Ramos-Romero, C.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, E.; Mas, A. Hepatitis E Virus in Industrialized Countries: The Silent Threat. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 9838041.

- Ahn, H.S.; Han, S.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Park, B.J.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.B.; Park, S.Y.; Song, C.S.; Lee, S.W.; Choi, C.; et al. Adverse fetal outcomes in pregnant rabbits experimentally infected with rabbit hepatitis E virus. Virology 2017, 512, 187–193.

- Lin, S.; Zhang, Y.-J. Advances in Hepatitis E Virus Biology and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2021, 13, 267.

- Xia, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.; Liu, P.; Zou, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhuang, H. Experimental infection of pregnant rabbits with hepatitis E virus demonstrating high mortality and vertical transmission. J. Viral Hepat. 2015, 22, 850–857.

- Bhatia, V.; Singhal, A.; Panda, S.K.; Acharya, S.K. A 20-year single-center experience with acute liver failure during pregnancy: Is the prognosis really worse? Hepatology 2008, 48, 1577–1585.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Kamili, S. Aetiology and prognostic factors in acute liver failure in India. J. Viral Hepat. 2003, 10, 224–231.

- Acharya, S.K.; Dasarathy, S.; Kumer, T.L.; Sushma, S.; Prasanna, K.S.; Tandon, A.; Sreenivas, V.; Nijhawan, S.; Panda, S.K.; Nanda, S.K.; et al. Fulminant hepatitis in a tropical population: Clinical course, cause, and early predictors of outcome. Hepatology 1996, 23, 1448–1455.

- Acharya, S.K.; Panda, S.K.; Saxena, A.; Gupta, S.D. Acute hepatic failure in India: A perspective from the East. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2000, 15, 473–479.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Kamili, S. Association of severity of hepatitis E virus infection in the mother and vertically transmitted infection in the fetus. JK Pract. 2006, 13, 70–74.

- Khuroo, M.S. Acute liver failure in India. Hepatology 1997, 26, 244–246.

- Shalimar; Acharya, S.K. Management in acute liver failure. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2015, 5, S104–S115.

- Dhiman, R.K.; Jain, S.; Maheshwari, U.; Bhalla, A.; Sharma, N.; Ahluwalia, J.; Duseja, A.; Chawla, Y. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure: An assessment of the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and King’s College Hospital criteria. Liver Transpl. 2007, 13, 814–821.

- Bertuzzo, V.R.; Ravaioli, M.; Morelli, M.C.; Calderaro, A.; Viale, P.; Pinna, A.D. Pregnant woman saved with liver transplantation from acute liver failure due to hepatitis E virus. Transpl. Int. 2014, 27, e87–e89.

- Babu, R.; Kanianchalil, K.; Sahadevan, S.; Nambiar, R.; Kumar, A. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure due to hepatitis E in a pregnant patient. Indian J. Anaesth. 2018, 62, 908–910.

- Ockner, S.A.; Brunt, E.M.; Cohn, S.M.; Krul, E.S.; Hanto, D.W.; Peters, M.G. Fulminant hepatic failure caused by acute fatty liver of pregnancy treated by orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology 1990, 11, 59–64.

- Patra, S.; Kumar, A.; Trivedi, S.S.; Puri, M.; Sarin, S.K. Maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnant women with acute hepatitis E virus infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 28–33.

- Khuroo, M.S. A Review of Acute Viral Hepatitides Including Hepatitis E. In Viral Hepatitis: Acute Hepatitis; Ozaras, R., Arends, J.E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 77–107.

- Navaneethan, U.; Al Mohajer, M.; Shata, M.T. Hepatitis E and pregnancy: Understanding the pathogenesis. Liver Int. 2008, 28, 1190–1199.

- Gouilly, J.; Chen, Q.; Siewiera, J.; Cartron, G.; Levy, C.; Dubois, M.; Al-Daccak, R.; Izopet, J.; Jabrane-Ferrat, N.; El Costa, H. Genotype specific pathogenicity of hepatitis E virus at the human maternal-fetal interface. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4748.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Kamili, S.; Dahab, S.; Yattoo, G.N. Severe fetal hepatitis E virus infection is the possible cause of increased severity of hepatitis E virus infection in the mother: Another example of mirror syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 99, S100.

- Naoum, E.E.; Leffert, L.R.; Chitilian, H.V.; Gray, K.J.; Bateman, B.T. Acute Fatty Liver of Pregnancy: Pathophysiology, Anesthetic Implications, and Obstetrical Management. Anesthesiology 2019, 130, 446–461.

- Celik, C.; Gezginc, K.; Altintepe, L.; Tonbul, H.Z.; Yaman, S.T.; Akyurek, C.; Turk, S. Results of the pregnancies with HELLP syndrome. Ren. Fail. 2003, 25, 613–618.

- Shalimar; Acharya, S.K. Hepatitis e and acute liver failure in pregnancy. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2013, 3, 213–224.

- Kar, P.; Karna, R. A Review of the Diagnosis and Management of Hepatitis E. Curr. Treat. Options Infect. Dis. 2020, 12, 1–11.

- Banait, V.S.; Sandur, V.; Parikh, F.; Murugesh, M.; Ranka, P.; Ramesh, V.S.; Sasidharan, M.; Sattar, A.; Kamat, S.; Dalal, A.; et al. Outcome of acute liver failure due to acute hepatitis E in pregnant women. Indian J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 26, 6–10.

- Satia, M.; Shilotri, M. Successful maternal and perinatal outcome of hepatitis E in pregnancy with fulminant hepatic failure. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 5, 2475–2477.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Kamili, S.; Khuroo, M.S. Clinical course and duration of viremia in vertically transmitted hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in babies born to HEV-infected mothers. J. Viral Hepat. 2009, 16, 519–523.

- Khuroo, M.S.; Khuroo, M.S.; Khuroo, N.S. Hepatitis E: Discovery, global impact, control and cure. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 7030–7045.

- Shrestha, A.; Gupta, B.P.; Lama, T.K. Current Treatment of Acute and Chronic Hepatitis E Virus Infection: Role of Antivirals. Euroasian J. Hepatogastroenterol. 2017, 7, 73–77.

- Zhu, F.C. Efficacy and safety of a recombinant hepatitis E vaccine in healthy adults: A large-scale, randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 895–902.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.F.; Huang, S.J.; Wu, T.; Hu, Y.M.; Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, H.; Jiang, H.M.; Wang, Y.J.; Yan, Q.; et al. Long-term efficacy of a hepatitis E vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 914–922.

- Wu, C.; Wu, X.; Xia, J. Hepatitis E virus infection during pregnancy. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 73.

- Joshi, R.M. Hepatitis E Virus: A Renewed Hope with Hecolin. Clin. Microbiol. Open Access 2015, 04.

- Wu, T.; Zhu, F.C.; Huang, S.J.; Zhang, X.F.; Wang, Z.Z.; Zhang, J.; Xia, N.S. Safety of the hepatitis E vaccine for pregnant women: A preliminary analysis. Hepatology 2012, 55, 2038.

- Li, M.; Li, S.; He, Q.; Liang, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, L. Hepatitis E-related adverse pregnancy outcomes and their prevention by hepatitis E vaccine in a rabbit model. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1066–1075.

- Zaman, K.; Dudman, S.; Stene-Johansen, K.; Qadri, F.; Yunus, M.; Sandbu, S.; Gurley, E.S.; Overbo, J.; Julin, C.H.; Dembinski, J.L.; et al. HEV study protocol: Design of a cluster-randomised, blinded trial to assess the safety, immunogenicity and effectiveness of the hepatitis E vaccine HEV 239 (Hecolin) in women of childbearing age in rural Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e033702.

- Hepatitis E vaccine: Why wait? Lancet 2010, 376, 845.