Phenols are compounds having a hydroxyl group attached to an aromatic ring such as a benzene or naphthalene ring. Several phenols that also possess one or more chlorine substituents attached to the aromatic ring have significant commercial importance, and these are the subject of this entry.

- selective chlorination

- phenols

- sulphuryl chloride

- sulphur-containing catalysts

- aromatic electrophilic substitution reactions

- monochlorination

- double chlorination

- para/ortho-isomer ratio

1. Commercial Applications of Chlorinated Phenols

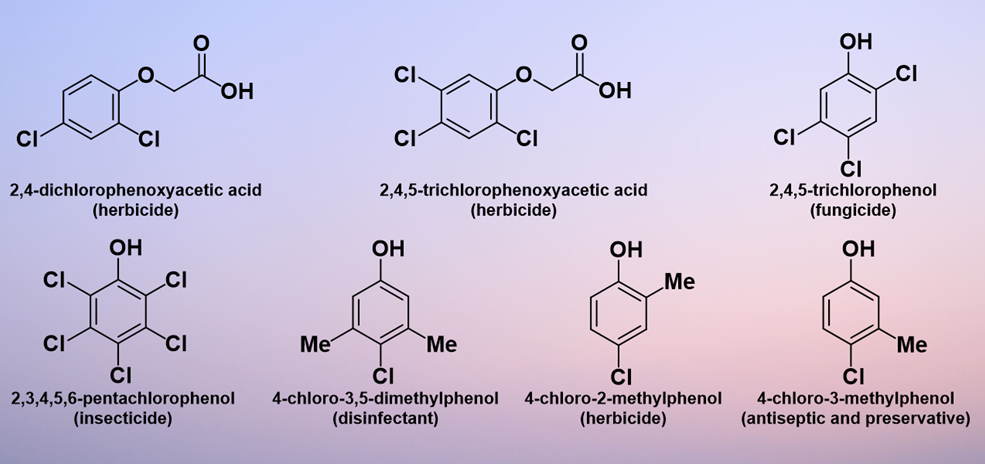

As a class of compounds, chlorinated phenols are of substantial commercial interest. Already by 1936, 2,3,4,5,6-pentachlorophenol was being used as a wood preservative in the US; in addition, it was involved in the preparation of paints, adhesives, ropes, and insulation [1]. 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), manufacture of which involves 2,4-dichlorophenol, was first synthesized in 1941 and has been commercially produced in many parts of the world since the 1950s[2]. Subsequently, the range of applications of chlorinated phenols has expanded and they are currently useful both as synthetic intermediates for more complicated products and as end products themselves. The range of areas of application includes antiseptics, herbicides, pesticides, and dyes[3]. For example, 2,4-D and 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4,5-T) were the first herbicides produced commercially for weed control[4] and 2,4-D is still in widespread use in 2021[5]. In addition, 2,4,5-trichlorophenol acts as a leather and wood fungicide[6], 2,3,4,5,6-pentachlorophenol is used as an insecticide[7], 4-chloro-3,5-dimethylphenol is used as a household and hospital disinfectant, 4-chloro-2-methylphenol is used as a herbicide, and 4-chloro-3-methylphenol is used as an antiseptic and preservative [8][9][10]. Figure 1 shows some of the most common industrial products containing chlorinated phenolic components.

Figure 1. Common industrial products containing chlorinated phenol components.

2. Synthesis of Chlorinated Phenols

Chlorinated phenols are almost always manufactured by direct chlorination of the parent phenols. Many approaches have been attempted for such chlorinations[12][13][14][15][17][16][18][19][20][21][22][23], including use of a range of different chlorinating agents, but either chlorine gas or sulfuryl chloride is usually used in commercial processes. Chlorination using chlorine is not very regioselective for many phenols, and several important products require a pure para-chloro derivative. A review in 2021[24] has reported on the development of various sulfur-containing catalysts and in particular poly(alkylene sulfide)s that render chlorination reactions of several simple phenols (Figure 2) highly selective with sulfuryl chloride as the reagent.

Figure 2. Chlorination of phenols using sulfuryl chloride (SO2Cl2) in the presence of sulfur-containing catalysts.

3. Para-Selective Chlorination of Phenols

Figure 3 shows some of the sulfur containing catalysts used recently for the para-selective chlorination of phenols[25][26][27][28][29][30][32][31][33][34].

Figure 3. Some sulfur-containing catalysts for the para-selective chlorination of phenols.

Chlorination of phenols in the presence of dialkyl sulfides 1 was very selective towards 4-chloro-m-cresol. For example, the use of 1 (R1 = n-Bu, R2 = n-Bu, iso-Bu, sec-Bu) in chlorination of m-cresol led to a para/ortho ratio of 17.1–17.3[26]. Cyclic sulfides 2 showed high para-selectivity in chlorination of phenols. For example, the use of unsubstituted tetrahydrothiopyran (2; R = H) in chlorination of o-cresol led to the production of 4-chloro-o-cresol in 96% yield with a para/ortho ratio of 45.7[30]. Dithiaalkanes 3 and in particular 5,18-dithiadocosane (3; m = 4, n = 12) have shown high para-selectivity in chlorination of m-cresol[28][29]. ω-Hydroxy-1-(methylthio)alkanes 4, ω-methoxy-1-(methylthio)alkanes 5, and 1,ω-bis(methylthio)alkanes 6 show somewhat similar trends as a function of the length of the spacer group in chlorination of phenols. For o-cresol, the highest para-selectivity was obtained with the shorter spacer groups (n = 2 or 3), while the longer spacer groups (n = 6 or 9) showed the highest para-selectivity in chlorination of m-cresol and m-xylenol, regardless of the substituent at the ω-position of the catalyst[30]. Cyclic and polymeric disulfides 7–10 were compared as catalysts in chlorination of phenols. For phenol, the longer spacers showed better para-selectivity than the smaller ones and the cyclic compounds were better than the polymers at delivering para-selectivity. For m-xylenol, the opposite was seen. For m-cresol, the spacer length seems to make no difference, but the cyclic compounds appear to be better than the polymers, while for o-cresol, the longer spacers were favored for the cyclic compounds and the shorter ones were better for the polymers[31]. Poly(alkylene sulfide)s 11 containing longer spacers led to a high para-selectivity in chlorination of m-cresol and m-xylenol, while the ones with shorter spacers were para-selective in chlorination of phenol, 2-chlorophenol, and o-cresol[33][34]. The use of catalysts 11 led to the highest yield and para-selectivity ever reported in chlorination of phenols and in particular m-xylenol. Indeed, catalysts 11 have been used commercially to produce 4-chloro-3,5-dimethylphenol.

References

- Badanthadka, M.; Mehendale, H.M. Chlorophenols. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences. Encyclopedia of Toxicology; 3rd ed.; pp. 896–899, 2014, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.00281-5.

- Garabrant, D.H.; Philbert, M.A. Review of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) epidemiology and toxicology. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2002, 32, 233–257, doi:10.1080/20024091064237.

- Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry; 6th ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1998.

- Fagan, K.; Pollak J.K. The effect of the phenoxyacetic acid herbicides 2,4,5-trichlorophenoxyacetic acid and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid as ascertained by direct experimentation. Residue Rev. 1984, 92, 29–58, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5266-5_2.

- EPA United State Environmental Protection Agency. Ingredients Used in Pesticide Products. 2,4-D. https://www.epa.gov/ingredients-used-pesticide-products/24-d (accessed on 01 August 2021).

- Favaro, G.; De Leo, D.; Pastore, P.; Magno, F.; Ballardin, A. Quantitative determination of chlorophenols in leather by pressurized liquid extraction and liquid chromatography with diode-array detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1177, 36–42, doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2007.10.106.

- Igbinosa, E.O.; Odjadjare, E.E.; Chigor, V.N.; Igbinosa, I.H.; Emoghene, A.O.; Ekhaise, F.O.; Igiehon, N.O.; Idemudia, O.G. Toxicological profile of chlorophenols and their derivatives in the environment: the public health perspective. Chemosphere 2011, 83, 1297–1306, doi:10.1155/2013/460215.

- World Health Organization, Stuart, M.C.; Kouimtzi, M.; Hill, S.R. ed.; WHO Model Formulary 2008.World Health Organization, 2009.

- Griffiths, C.; Barker, J.; Bleiker, T.O.; Chalmers, R.; Creamer, D. Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology; 9th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2017.

- Digison MB. A review of anti-septic agents for pre-operative skin preparation. Plast. Surg. Nurs. 2007, 27, 185–189, doi:10.1097/01.PSN.0000306182.50071.e2.

- Sullivan, J.D. para-Halogenation of phenols. US Pat. US 2,777,002, 1957. Chem. Abstr. 1957, 51, 77109.

- Nishihara, A.; Kato, H. Chlorination of phenols. Jpn. Pat. JP4,9035,344A, 1974. Chem. Abstr. 1974, 81, 120196.

- March, J. Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms and Structure, 4th ed.; Wiley: New York, USA, 1992.

- Xin, H.; Yang, S.; An, B.; An, Z. Selective water-based oxychlorination of phenol with hydrogen peroxide catalysed by manganous sulfate. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 13467–13472, doi:10.1039/C7RA00319F.

- Nahide, P.D.; Ramadoss, V.; Juárez-Ornelas, K.A.; Satkar, Y.; Ortiz‐Alvarado, R.; Cervera‐Villanueva, J.M.J.; Alonso‐Castro, Á.J.; Zapata‐Morales, J.R.; Ramírez‐Morales, M.A.; Ruiz‐Padilla, A.J.; Deveze‐Álvarez, M.A.; Solorio‐Alvarado, C.R. In situ formed IIII -based reagent for the electrophilic ortho-chlorination of phenols and phenol ethers: The use of PIFA-AlCl3 System. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 485–493, doi:10.1002/ejoc.201701399.

- Xiong, X.; Yeung, Y-Y. Ammonium salt-catalyzed highly practical ortho-selective monohalogenation and phenylselenation of phenols: Scope and applications. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4033–4043, doi:10.1021/acscatal.8b00327.

- Bugnet, E.A.; Brough, A.R.; Greatrex, R.; Kee, T.P. On the para-selective chlorination of ortho-cresol. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 8059–8065, doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00996-1.

- Watson, W.D. Chlorination with sulfuryl chloride. US Pat. US 3,920,757A, 1975. Chem. Abstr. 1976, 84, 43612.

- Watson, W.D. The regioselective para chlorination of 2-methylphenol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1976, 17, 2591–2594, doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)91742-8.

- Watson, W.D. Regioselective para-chlorination of activated aromatic compounds. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 2145–2148, doi:10.1021/jo00212a029.

- Binns, J.S.; Braithwaite, M.J. p-Chlorophenol. Ger. Offen. DE2,726,436A1, 1977. Chem. Abstr. 1978, 88, 120784.

- Ogata, Y.; Kimura, M.; Kondo, Y.; Katoh, H.; Chen, F.-C. Orientation in the chlorination of phenol and of anisole with sodium and t-butyl hypochlorites in various solvents. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin. Trans. 2 1984, 451–453, doi:10.1039/P29840000451.

- Olah, G.A.; Ohannesian, L.; Arvanaghi, M. Synthetic methods and reactions; 127. Regioselective para halogenation of phenols, phenol ethers and anilines with halodimethylsulfonium halides. Synthesis 1986, 868–870, doi:10.1055/s-1986-31813.

- Smith, K.; El-Hiti, G.A. Development of efficient and selective processes for the synthesis of commercially important chlorinated phenols. Organics 2021, 2, 142–160, doi:10.3390/org2030012.

- Tzimas, M.; Smith, K.; Brown, C.M.; Payne, K. Chlorination of aromatic compounds and catalysts therefor. Eur. Pat. EP0866049A2, 1998. Chem. Abstr. 1998, 129, 260219.

- Smith, K.; Tzimas, M.; Brown, C.M.; Payne, K. Dialkyl sulfides as selective catalysts for the chlorination of phenols. Sulfur Lett. 1999, 22, 89–101.

- Smith, K.; Williams, D.; El-Hiti, G.A. Regioselective chlorination of phenols in the presence of tetrahydrothiopyran derivatives. J. Sulfur Chem. 2019, 40, 529–538, doi:10.1080/17415993.2019.1620230.

- Tzimas, M.; Smith, K.; Brown, C.M.; Payne, K. Chlorination of aromatic compounds and catalysts therefor. Eur. Pat. EP0866048A2, 1998. Chem. Abstr. 1998, 129, 275696.

- Smith, K.; Tzimas, M.; Brown, C.M.; Payne, K. Dithiaalkanes and modified Merrifield resins as selective catalysts for the chlorination of phenols. Sulfur Lett. 1999, 22, 103–123.

- Smith, K.; Al-Zuhairi, A.J.; Elliot, M.C.; El-Hiti, G.A. Regioselective synthesis of important chlorophenols in the presence of methylthioalkanes with remote SMe, OMe or OH substituents. J. Sulfur Chem. 2018, 39, 607–621, doi:10.1080/17415993.2018.1493111.

- Smith, K.; Al-Zuhairi, A.J.; El-Hiti, G.A.; Alshammari, M.B. Comparison of cyclic and polymeric disulfides as catalysts for the regioselective chlorination of phenols. J. Sulfur Chem. 2015, 36, 74–85, doi:10.1080/17415993.2014.965170.

- Smith, K.; El-Hiti, G.A.; Al-Zuhairi, A.J. The synthesis of polymeric sulfides by reaction of dihaloalkanes with sodium sulfide. J. Sulfur Chem. 2011, 32, 521–531, doi:10.1080/17415993.2011.616589.

- Smith, K.; Hegazy, A.S.; El-Hiti, G.A. The use of polymeric sulfides as catalysts for the para-regioselective chlorination of phenol and 2-chlorophenol. J. Sulfur Chem. 2020, 41, 1–12, doi:10.1080/17415993.2019.1688815.

- Smith, K.; Hegazy, A.S.; El-Hiti, G.A. para-Selective chlorination of cresols and m-xylenol using sulfuryl chloride in the presence of poly(alkylene sulfide)s. J. Sulfur Chem. 2020, 41, 345–356, doi:10.1080/17415993.2020.1740226.