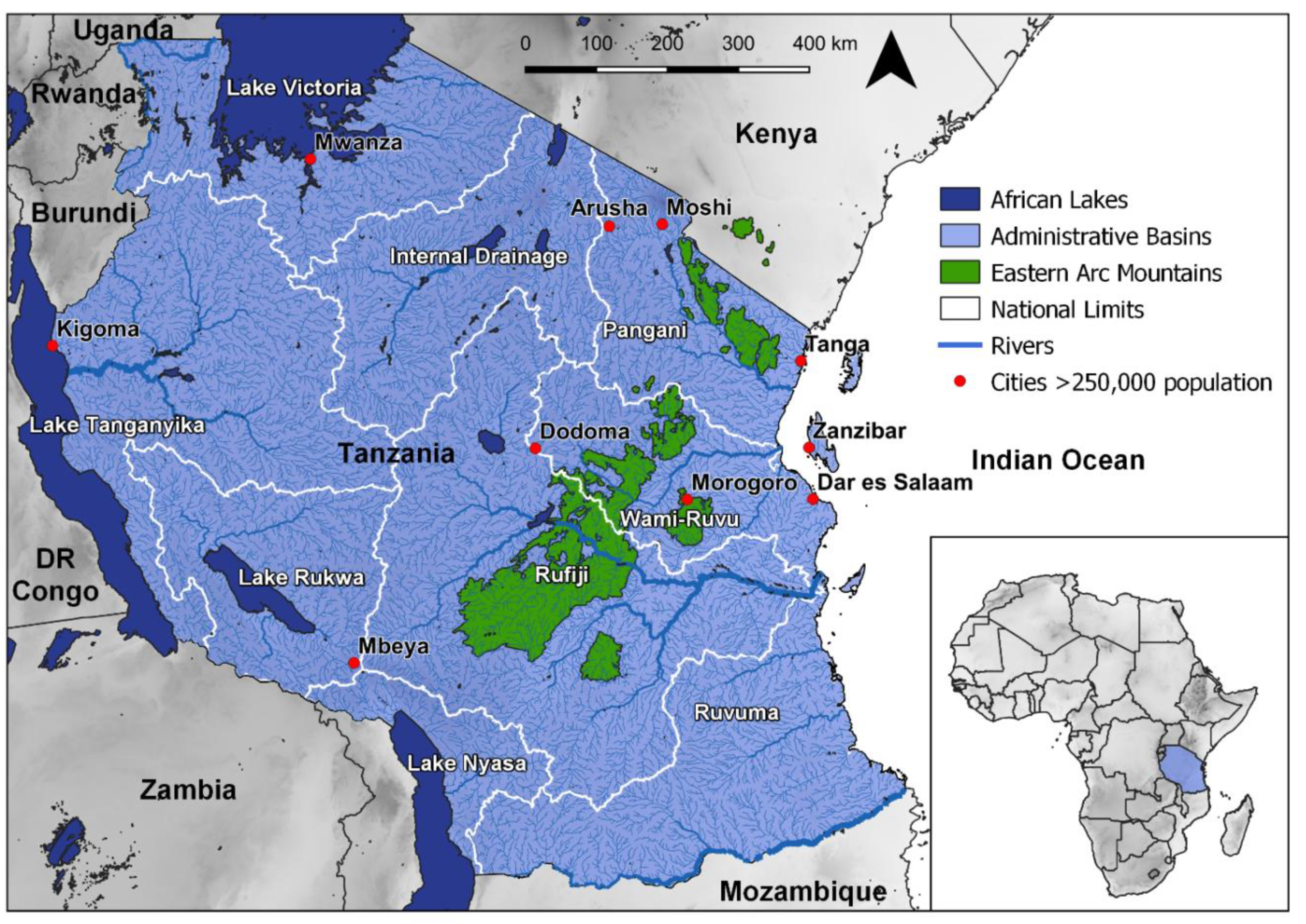

Mainland Tanzania (885,800 km2), is located along the Indian Ocean coastline, neighboured by Kenya to the north and Mozambique to the south. Mainland Tanzania’s western and southern borders cross through the African Great Lakes—Victoria, Tanganyika, and Nyasa. Several major river systems drain mainland Tanzania (Figure 1). The Pangani, Wami, Ruvu, Rufiji, and Ruvuma rivers flow eastward, descending from Eastern Arc Mountain blocks, winding through coastal forests, and eventually draining into the Indian Ocean. Much of the country’s human population, including urban centres like Dar es Salaam (6 million people) and Dodoma (2 million people), and major agricultural regions are located in these basins. Several other rivers such as the Malagarasi, Kagera, Ruhuhu and Mara flow towards the Tanzania Lake basins of Tanganyika, Victoria and Nyasa.

Figure 1. Tanzania is divided into nine administrative basins under the Tanzanian Ministry of Water, which generally follow natural river or lake basin boundaries. The country’s largest river systems are the Rufiji, which drains to the Indian Ocean, and the Malagarasi, draining westward to Lake Tanganyika.

Most of Tanzania experiences a marked difference in precipitation between wet and dry seasons; river flows reflect this seasonality. Some rivers experience a bi-modal hydrograph, with peaks in flow that correspond to the long (masika) and short (vuli) rains; other rivers exhibit a uni-modal hydrograph [6,7]. Rivers are key ecosystem elements of several of Tanzania’s protected areas and critical to wildlife survival, particularly during dry seasons when other sources of water may dry out. For example, in the Serengeti National Park, the Mara River provides one of the only perennial sources of water for large wildlife and acts as a guidepost for wildebeests that cross the river multiple times during their annual migration (Figure 2a). Saadani National Park, located at the confluence of the Wami River with the Indian Ocean, protects the Wami’s estuary region, which also supports one of the most productive prawn fisheries along the East African coastline; intensive periods of prawn fishing coincide with high flows in the Wami River (Figure 2b) [8].

Figure 2. (a) Wildebeest cross the Mara River multiple times during their annual migrations in the Serengeti-Mara region of northern Tanzania and southern Kenya. This event draws thousands of tourists annually. Photo: D.M. Post. (b) The lower Wami River and its estuary are important parts of Saadani National Park and considered nursery areas for prawns. Photo: E.P. Anderson.

Tanzanian rivers originating in Eastern Arc Mountain blocks fall into a newly recognized category of Tropical Montane Rivers, as defined by Encalada et al. [9]. Eastern Arc rivers exhibit characteristics of Tropical Montane Rivers such as: Predictable change in water temperature with elevation; frequent disturbance events like landslides or extreme hydrologic events; habitat heterogeneity; and connectivity with headwater and lowland areas. Downstream, the deltas of many Eastern Arc-origin rivers—notably the Rufiji and Ruvuma—are recognised as areas of ecological and social importance in the Western Indian Ocean. These rivers export high loads of sediments from Eastern Arc Mountain blocks, which form and maintain floodplain areas in lower gradient parts of their basins near the Indian Ocean coastline, in combination with tidal influences [10]. Connecting the mainland to the coast, riverine floodplains, and deltas contain nursery areas for aquatic biota, act as sinks for carbon, offer defence against storms, and provide innumerable ecosystem services to human populations [10,11].

The current state of knowledge of riverine biodiversity in Tanzania is limited. For example, Eccles’ Field Guide to the Freshwater Fishes of Tanzania, the primary reference on this faunal group, was published more than 25 years ago [12]. Species records for most river basins in Eccles [12] were based on fisheries information and very limited collections and therefore likely underestimate fish species richness, particularly for endemic, rare, and non-fisheries species. Even today, most rivers in Tanzania still have not been extensively sampled for fishes or other aquatic biota; a similar situation is observed across other East African countries as well [13].

Given this scenario, several recent initiatives have aimed to elevate scientific knowledge of freshwater fishes and macroinvertebrates inhabiting flowing water environments in Tanzania. An estimated 1257 freshwater fish species have been documented in freshwaters of continental Tanzania, of which at least 773 are found in the lakes Victoria, Tanganyika and Nyasa [14]. For freshwater mollusks, an estimated 159 species have been documented, 76.5% of which are gastropods and 23.5% bivalves (L. Kaaya, unpublished data). Tropical montane rivers draining Eastern Arc mountain blocks are likely to harbour a highly endemic freshwater fauna, given that this region is renowned for high species richness and endemism across multiple taxonomic groups—plants, birds, mammals and amphibians, in particular [9,14–17]. For example, at least three endemic Odonata (dragonflies and damselflies) are known to spend their reproductive stages exclusively in Eastern Arc montane rivers [18], and in 2007, an ichthyofaunal survey of Eastern Arc rivers reported 75 fish species, including 11 newly described [19]. Similarly, a rapid assessment of the aquatic biota of the Wami and Ruvu Basins completed in 2013–2014 added new species records of fishes and amphibians for those basins [20]. Finally, recent studies in classifying river ecosystems, coupled with the development of bio-assessments for macro-invertebrates in Rufiji, Wami-Ruvu and Pangani, have increased awareness of freshwater biota, and the high level of discovery that remains [21–23].

Environmental flow assessment studies (see Table 1 and subsection below) have included snapshot sampling for fishes and macro-invertebrates, providing additional data and in some cases the first field sampling campaigns for Tanzanian rivers [24–29]. For example, an initial environmental flow assessment in the Wami River basin identified five different sites where field sampling was conducted during both dry and wet seasons in 2007, including sampling of riparian biota, macroinvertebrates and fishes. Of the 37 species of fish that were previously reported from the Wami River basin [12], 28 were collected during these sampling events [4]. Similarly, an environmental flow assessment conducted in the Rufiji River basin documented 27 species of fish from five sampling sites, about half of the species known from the region. This effort also gathered evidence on the ecology of several fishes, including data on longitudinal migrations of several species (e.g., Labeo spp., Hydrocynus vittatus, Anguilla spp., Alestes sp., Barbus macrolepis and Mormyrus sp.) and lateral migrations between the river and floodplains for other species (e.g., Clarias sp. Brycinus affinis, and Schlbe moebusii) [27]. This kind of information is critical to understanding the ecological linkages to river flows, as many of these migrations are linked to flow pulses or flooding events

Table 1. Summary of selected environmental flow assessments (EFA) realized for Tanzanian rivers since the passage of the National Water Policy in 2002.

|

River System |

Timeline for EFA |

Approach/Methodology |

Key Riverine and Riparian Features; Protected Areas |

Challenges for River Conservation and Management |

References |

|

Pangani |

2003–2005 |

Used modified downstream response to imposed flow transformation (DRIFT) approach to develop scenarios |

Eastern Arc montane streams and forests; Mt. Kilimanjaro National Park |

Competition for land; agricultural expansion; urban and rural water interests |

[4,30] |

|

Great Ruaha (tributary of Rufiji River) |

2003–2005 |

Initial EFA with semi-holistic approach; used desktop reserve model and flow duration curve analysis based on the hydrologic data, with some information on the ecology of Ruaha National Park |

Ruaha National Park; Usangu Plans and wetlands, designated as an important bird area by BirdLife International |

Expansion of agriculture and livestock grazing on the Usangu Plains; cease of dry season flows in the Great Ruaha River and drying out of wetland areas |

[4,31–33] |

|

2007 |

Full EFA using building block methodology |

[34] |

|||

|

Mara (tributary of Lake Victoria) |

2005–2012 |

Modified building block methodology; field campaigns were conducted over several years and two sets of flow recommendations were developed, the first focused on the Kenyan side and the second including Kenya and Tanzania |

Serengeti National Park and Mara wetlands complex; Mara River is one of only perennial rivers in the region |

Transboundary nature of the basin (65% in Kenya; 35% in Tanzania) |

[4,24,31,35] |

|

2018–present |

Focus on Tanzanian side of the Mara River, using PROBFLO |

[36] |

|||

|

Wami |

2007, 2012–2013 |

Initial EFA using a modified building block methodology; flow recommendations later revisited after additional fieldwork |

Eastern Arc montane rivers; Wami estuary; Saadani National Park |

Expansion of irrigated agriculture; domestic water supply withdrawals; freshwater inflows to the Wami estuary and surrounding Saadani National Park |

[4,26] |

|

2014–2015 |

Study of freshwater inflow requirements for the Wami River estuary and Saadani National Park |

[37] |

|||

|

Ruvu |

2012–2014 |

Initial EFA using modified building block methodology |

Eastern Arc montane rivers; estuary and coastal rivers; water supply for Dar es Salaam |

Increasing human population growth and industrialisation in Dar es Salaam, and related demands for water |

[25] |

|

Rufiji |

2014–2016 |

Application of a desktop reserve model and a modified building block methodology; additional consideration given to social-ecological significance of river flows |

Wetlands, river floodplains and coastal zones |

Growth of irrigated agriculture, particularly in the Kilombero River Valley |

[27] |

Knowledge limitations on Tanzanian rivers are not limited to obligate freshwater biota. Numerous other species in Tanzania are semi-aquatic or have life histories dependent on freshwater systems, and the flow-ecology linkages that are critical to these species’ survival is a growing area of research. For example, hippopotami (Hippopotamus amphibius; hippos hereafter), native to many areas of Tanzania, need to submerge themselves in water during the daytime to aid in thermoregulation and to avoid skin damage from solar radiation. Recent studies of hippos in Tanzania’s Great Ruaha River suggest that alterations of aquatic habitats, in particular surface water withdrawals, are the largest threat to hippo distribution and abundance, and the species’ overall viability [38]. Other studies by Stears et al. [39] in the Ruaha River system have suggested that hippos typically stay <800 m from riverbanks, and that the importance of river flow to hippo ecology and population dynamics varies by life stage. Additionally, the perennial Tarangire River, sustained by its associated wetland and swamp ecosystems, provides crucial dry season refuge for larger numbers of mammals including a high density of elephants and other plains game animals such as the African buffaloes (Synceros caffer), zebra (Equus burchellii) and the wildebeest (Connochaetes sp). Understanding of the freshwater needs of these organisms is increasing, but still limited.

Finally, a relatively new line of research has started to examine the interactive effects of large animal resource subsidies and hydrology on river ecosystem ecology. Studies along the Mara River of Kenya and northern Tanzania have documented the strong role that hippos play in river nutrient and oxygen dynamics, as one individual hippo may contribute an estimated six kg/day of waste [40]. Aggregations of hippos in pools can lead to an accumulation of organic matter, that when flushed by a pulse or peak hydrologic event, can cause a large drop in dissolved oxygen, often leading to fish kills [41]. The annual wildebeest migration is an additional source of animal resource subsidies to the Mara River and also somewhat hydrologically mediated [42]. Wildebeests cross the Mara River multiple times during the migration and many do not survive, resulting in animal carcasses in the channel. When these crossings occur during low flows, there is chance for increased predation by crocodiles on wildebeests, but when the crossings occur during high flows, the likelihood of drowning is increased.

This publication can be found here:https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/11/12/2612

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia