Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Chitin, a major structural component of the fungal cell wall, synthesized via the activityof the enzyme chitin synthase (chs), has become a high-profifile target for investigating the effect on morphology, development and pathogenicity of filamentous fungi. Besides, disruption of chitin biosynthesis can modify the mycelial morphology of filamentous fungi and regulate the biosynthesis of the target metabolites during submerged fermentation. Thus, we summarize the classifification, structure and function of chs enzymes, the biosynthetic pathway of chitin of filamentous fungi.

- chitin

- mycelia morphology

- filamentous fungi

- development

1. Structure and Function of Chitin

After cellulose, chitin is the second most abundant natural polysaccharide, occurring widely in the exoskeletons of insects, crustaceans, and mollusks; it is also an important structural polysaccharide in fungal cell walls [1-3]. Notably, the chitin content in the fungal cell wall differs according to the morphological phase, accounting for only 1–2% of yeast cell wall dry weight [4,5], but reaching up to 10–20% of the cell wall dry weight of filamentous fungi (Aspergillus) [6]. Moreover, the content of chitin in the hyphal walls of Candida albicans is three times higher than that of other yeasts [7], whereas, in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Blastomyces dermatitidis, it is 25–30% higher than that in the yeast phase [8]. Chitin is a linear copolymer of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (GlcNAc) and d-glucosamine units, linked by a β-(1–4) glycosidic bond, although predominantly comprising GlcNAc units [2]. Chitin chains of more than 100 and 190 GlcNAc monomers in length have been reported in cell walls and bud scars, respectively [1][2]. In addition, crystalline structural determinations have revealed that chitin can exist in three different forms, namely, α-, β-, and γ-chitin, representing antiparallel, parallel, and alternated arrangements of polymer chains, respectively [3][4]. In fungi, α-chitin is the major structural form [5], and γ-chitin is mainly found in the beetle family Lucanidae [6].

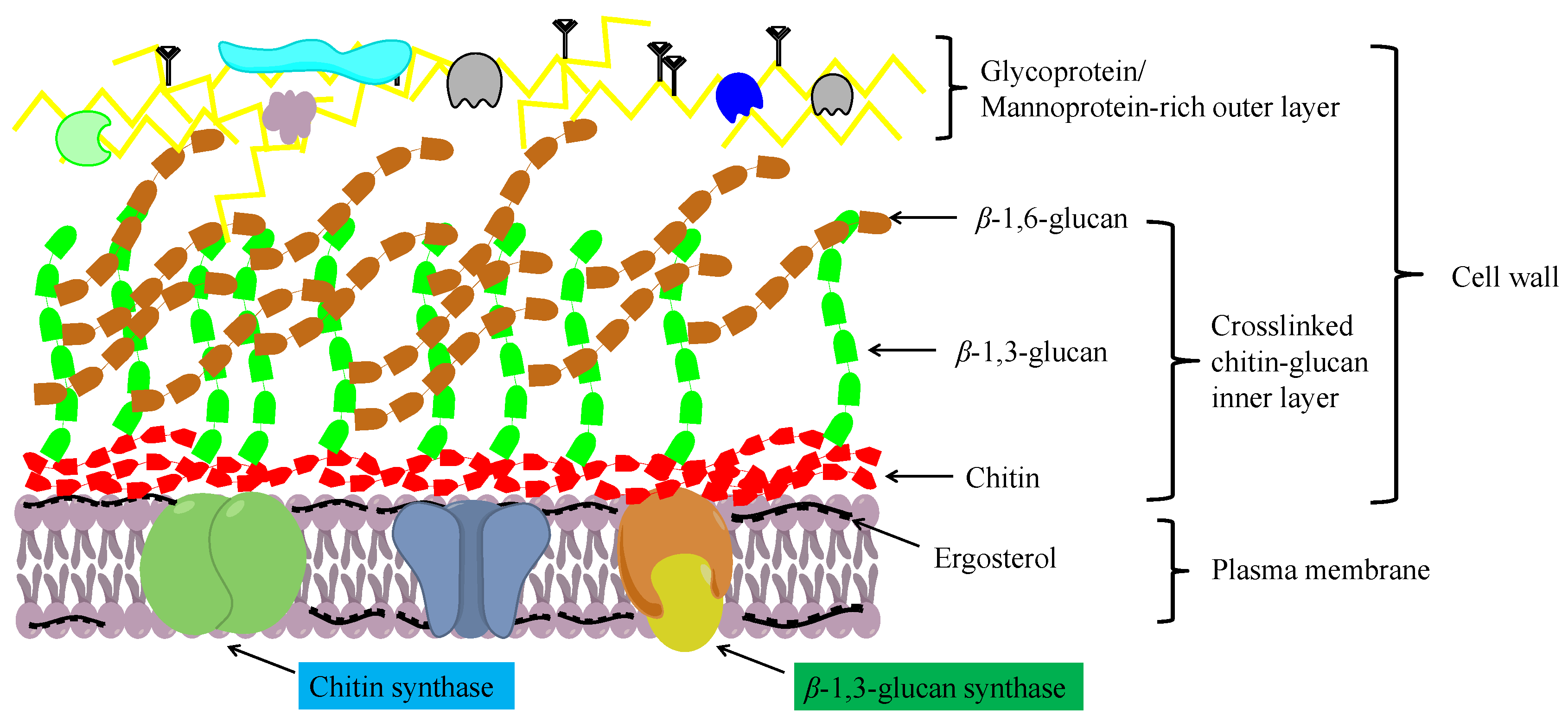

Chitosan is an important chitin derivative, generated by removing the acetyl group of chitin, either via treatment with concentrated alkali or the activity of chitin deacetylases. Chitin and its derivatives (chitosan and glucosamine series) have important applications in medicine and in the chemical industry, and as functional foods. Chitin and chitosan are considered advantageous biocompatible materials that can be used to augment or replace any tissue, organ, or function of the body [7][8]. Moreover, owing to their notable biological activities, including antibacterial, antifungal, antitumor, immunoregulatory, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, chitosan oligosaccharides have gained widespread application in the treatment and prevention of multiple life-threatening diseases and disorders, including cancer, heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and serious infections [9]. In addition, chitin and chitosan have a high absorptive capacity for wastewater pollutants, and thus have application potential in industrial wastewater treatment [10]. In filamentous fungi, chitin molecules form intrachain hydrogen bonds, facilitating assembly into fibrous microfibrils that form a basket-like scaffold surrounding cells. These fibrous microfibrils are characterized by considerable tensile strength, thereby maintaining cell wall integrity. As depicted in Figure 1, the cell wall comprises a twin-layer structure, the innermost layer of which is a relatively conserved structural skeletal layer (crosslinked chitin-glucan inner layer) comprising chitin and β-(1,3)-branched glucan, whereas the heterogeneous outer layer consists of other polysaccharides and glycoproteins [11][12]. The β-(1,3):β-(1,6)-branched glucan of the cell wall is bound to proteins or other polysaccharides, the composition of which may vary according to the fungal species, although it generally comprises highly mannosylated glycoproteins and mannoproteins. Chitin plays multiple roles in fungal species, including the maintenance of cell structural integrity, regulation of epithelial adhesion, the linkage between the cell wall and capsule, and antifungal resistance [17-19]. Accordingly, chitin is a key factor in maintaining normal cell growth and metabolism in filamentous fungi.

Figure 1. A schematic diagram showing the structure of the fungal cell wall.

2. The Chitin Biosynthetic Pathway

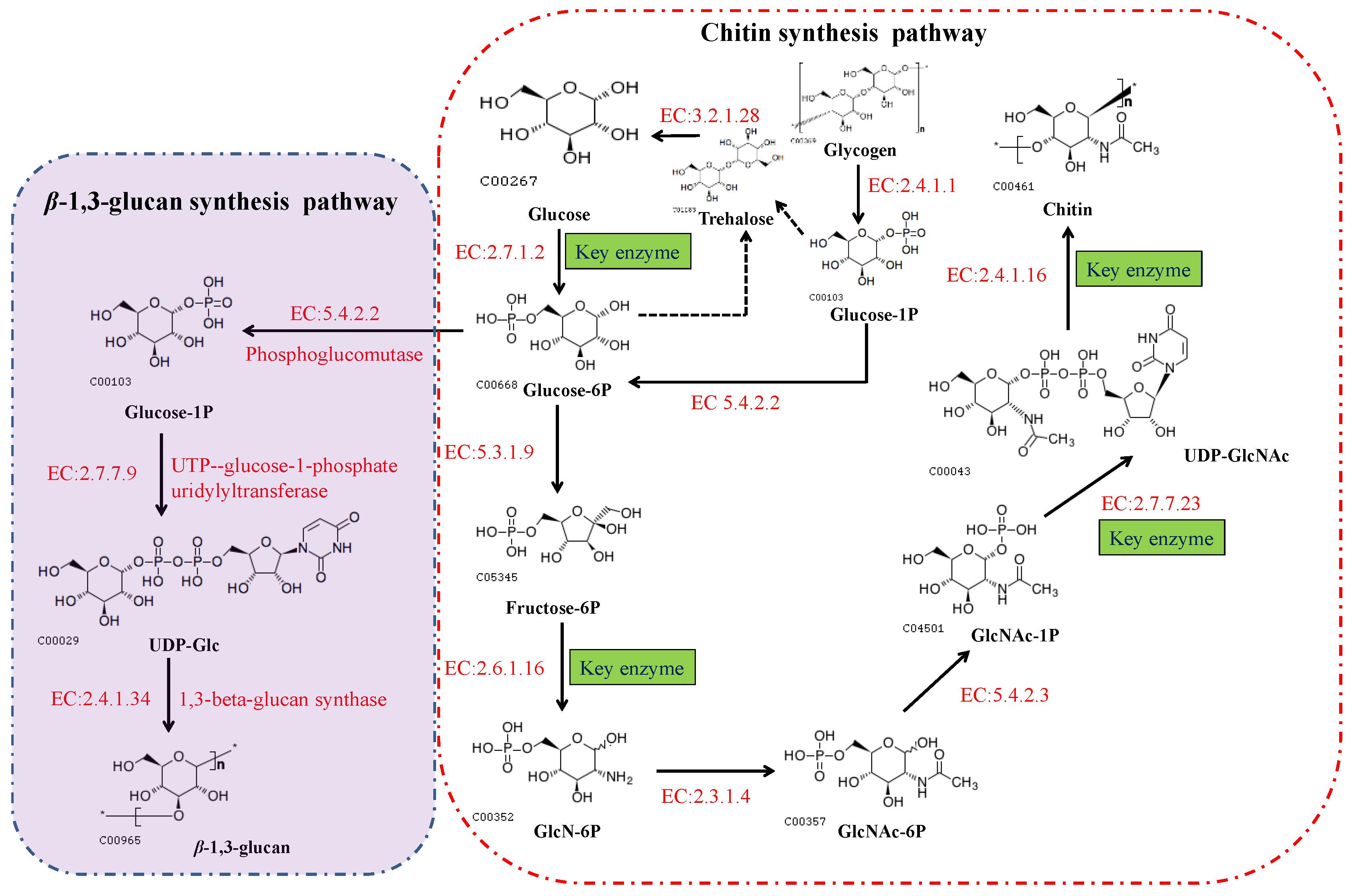

In fungi, chitin is synthesized via a highly complex biosynthetic pathway involving a multifarious series of biochemical and physiological processes [13]. As substrates, glucose or one of its storage compounds (glycogen or trehalose) undergoes bioconversion to a polymer of the amino sugar GlcNAc via a series of enzymatic reactions divided into three sets of sub-reactions [13]. In the first set of sub-reactions (Figure 2), the biosynthesis of GlcNAc-1P proceeds via three steps: the substrate, fructose-6-phosphate (fructose-6P), generated from glycolysis (or the Embden–Meyerhof–Parnas (EMP) pathway), and trehalose are mobilized by hydrolysis to glucose catalyzed by trehalase [EC:3.2.1.28], and glycogen is converted to glucose-1-P by glycogen phosphorylase [EC:2.4.1.1]. During this stage, glucokinase [EC:2.7.1.2] or hexokinase [EC:2.7.1.1], and glutamine-fructose 6-phosphate transaminase (isomerizing) [EC:2.6.1.16] are the rate-limiting enzymes. In addition, glucose-6P can be used for the biosynthesis of β-(1,3) glucan via three reactions catalyzed by the enzymes phosphoglucomutase [EC:5.4.2.2], UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase [EC:2.7.7.9], and 1,3-β-glucan synthase [EC:2.4.1.34]. In the second set of sub-reactions, GlcNAc-1P is catalyzed to generate the activated molecule amino sugar UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) via the action of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase [EC:2.7.7.23], an essential enzyme for chitin synthesis. In the final set of sub-reactions, the enzyme chs [EC:2.4.1.16] catalyzes a polymerization reaction to synthesize chitin using the activated UDP-GlcNAc as a sugar donor. The first two sets of sub-reactions occur within the cell cytoplasm, while the third reaction occurs in the chitosome, located within the plasma membrane of cells in the hyphal tips and cell cross-walls of filamentous fungi [14]. In the chitin biosynthetic pathway, glutamine-fructose 6-phosphate transaminase [EC:2.6.1.16], UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase [EC:2.7.7.23], and chs [EC:2.4.1.16] serve as the rate-limiting enzymes that dictate the rate at which chitin is synthesized, and are highly regulated in cells. Among these enzymes, chs catalyzes the final reaction, which is specifically and directly associated with the biosynthesis of chitin, and accordingly, is acknowledged to be the key enzyme in chitin biosynthesis. As described in the Introduction section, chs plays a vital role in cell development and the mycelial morphology of filamentous fungi, thereby having a prominent role in the application of MEMFF.

Figure 2. The biosynthetic pathways of chitin and β-(1,3) glucan in fungi. These pathways can also be viewed at the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes website (https://www.kegg.jp/pathway/map00520, accessed on 11 September 2021).

3. Classification of Chitin Synthase

Based on amino acid sequence homology, the chs enzyme family can be grouped into seven classes (I to VII), with different fungal species expressing varying numbers of chs genes [15]. In 2019, researchers summarized three chs genes (classes I–III) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, four in Candida, and six to ten in filamentous fungi [16]. Among the seven classes, CHS III, V, VI, and VII are found exclusively in filamentous fungi [17]. In the same year, in their review of fungal chitin synthesis and degradation, Yang and Zhang described the members of the seven classes of chitin synthase in different fungi [12]. However, since then, details of chs genes and their classification have not been furthered. We found differences in the number of chs genes in Saccharomycotina, although these are generally grouped into three classes (CHS I–III). For instance, there are six (as opposed to the originally reported three), five, and four chs genes in S. cerevisiae S288c, Candida orthopsilosis Co 90-125, and Candida tropicalis MYA-3404, respectively, whereas eight chs genes have been identified in Sugiyamaella lignohabitans CBS 10342. Except for those in goldfish (seven chs genes), there are generally few chs genes in animals, including Eutheria, Amphibia, and Euteleostomi. Notably, the number and classes of chs genes in fungal genera are distinctly higher than those in the species of Saccharomycotina and animals. For example, among species of Pezizomycotina, such as Aspergillus fumigatus, Neurospora crassa, Cordyceps militaris, and Purpureocillium lilacinum, chs genes are generally grouped into seven classes, with seven to nine genes in each. Moreover, certain hypothetical proteins are identified as chs enzymes in Fusarium graminearum and Pestalotiopsis fici, thereby indicating the potential occurrence of up to 10 types of chs. Strains of filamentous fungi in the genus Monascus, an important industrialized fermentative microorganism, are noted for their production of MSMs, including Monascus pigments and monacolin K. In our laboratory, we have sequenced the whole genomes of M. purpureus LQ-6 (accession number of PRJNA503091) and its mutant strain M183 (accession number of JAACNI000000000) based on the combined application of single-molecule real-time DNA sequencing and next-generation sequencing. Accordingly, we identified eight genes encoding chs enzymes, the classification of which appears to be complex. In addition, nine genes encoding chs enzymes (including three hypothetical proteins) have been identified in the genome of M. purpureus HQ1 (accession number of VIFY00000000), mainly classified as CHS I, II, III, V, and VII. The larger number of chs genes in filamentous fungi compared to Saccharomycotina reflects the greater complexity of hyphal development and polarized growth, as well as a higher cell wall chitin content.

Table 1. The members of the chitin synthase family in a section of diverse fungi. chs, represents the gene of chitin synthase; CHS, represents the class of the members of chs family. The genes encoding hypothetical proteins, but mostly like chs, are marked in red.

| Organism | T-Number | The Members of Chitin Synthase | Number of Genes |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288c | T00005 | YBR023C, chs 3 | YBR038W, chs 2 | YNL192W, chs 1 | YLR330W, chs 5 | YJL099W, chs 6 |

YHR142W, no KO assigned | (RefSeq) chs7; chs 7p |

6 | ||||

| Lodderomyces elongisporus NRRLYB-4239 | T01116 | LELG_05384, chs 2 | LELG_05013, chs 1 | LELG_02210, chs 2 | LELG_00298, chs 3 | LELG_00300, chs 3 | 5 | |||||

| Candida tropicalis MYA-3404 | T01115 | CAALFM_ C113110CA, chs 3 |

CAALFM_ C300710WA, chs 8 |

CAALFM_ C702770WA, chs 1 |

CAALFM_ CR09020CA, chs 2 |

4 | ||||||

| Candida orthopsilosis Co 90-125 |

T02488 | CORT_0A01870, chs 3 | CORT_0D06430, chs 8 | CORT_0G01660, chs 2 | CORT_0H01960, chs 1 | CORT_0H01970, chs 1 | 5 | |||||

| Sugiyamaella lignohabitans CBS 10342 | T05270 | AWJ20_11, chs 6 | AWJ20_12, chs 3 | AWJ20_13, chs 3 | AWJ20_1163, chs 2 | AWJ20_1500, chs 2 | AWJ20_3769, chs 1 | AWJ20_4861, chs 3 | AWJ20_4948, chs 3 | 8 | ||

| Xenopus laevis (African clawed frog) | T01010 | 108717413, chs 2 | 108716131, chs 2 |

2 | ||||||||

| Xenopus tropicalis (tropical clawed frog) | T01011 | 105947355, chs 2-like isoform X1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Carassius auratus (goldfish) | T07313 | 113057339 CHS 2-like | 113061218 CHS 1-like | 113061224 CHS 1-like | 113061225 CHS 1-like | 113061526 CHS 1 | 113061527 CHS 1-like | 113113123 CHS 2-like |

7 | |||

| Pyricularia oryzae 70-15 | T01027 | MGG_09962, chs 4 |

MGG_06064, chs D |

MGG_09551, chs 3 |

MGG_13013, chs 8 |

MGG_13014, CHS V |

MGG_01802, chs1 |

MGG_04145, chs 2 |

7 | |||

| Fusarium graminearum | T01038 | FGSG_01272, chs 4 |

FGSG_01949, chs D |

fgr:FGSG_12039, chs 6 |

fgr:FGSG_01964, hypothetical protein |

fgr:FGSG_02483, chs 2 |

fgr:FGSG_10116, chs 1 |

fgr:FGSG_10327, chs 3 |

fgr:FGSG_10619, hypothetical protein |

fgr:FGSG_03418, chs 1 |

fgr:FGSG_06550, hypothetical protein |

10 |

| Purpureocillium lilacinum | T05029 | VFPFJ_00650, chs D |

VFPFJ_00666, chs 6 |

VFPFJ_00667, chs 6 |

VFPFJ_03324, chs D |

VFPFJ_04443, chs A |

VFPFJ_08553, chs G |

VFPFJ_08866, chs A |

VFPFJ_11040, chs |

8 | ||

| Pestalotiopsis fici W106-1 | T04924 | PFICI_01118, chs 1 | PFICI_01446, chs 4 | PFICI_04362, hypothetical protein | PFICI_04363, hypothetical protein | PFICI_05017, chs D | PFICI_05238, chs 2 | PFICI_06085, chs 3 | PFICI_07201, chs 1 | PFICI_12982, hypothetical protein | PFICI_13513, chs 1 | 10 |

| Botrytis cinerea B05.10 | T01072 | BCIN_01g02520, CHS IIIb | BCIN_01g03790, CHS IV | BCIN_04g03120, CHS IIIa | BCIN_07g01300, CHS VII | BCIN_09g01210, CHS I | BCIN_12g01380, CHS II | BCIN_12g05360, CHS VI | BCIN_12g05370, CHS V | 8 | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus Af293 | T01017 | AFUA_4G04180, chs B | AFUA_8G05630, chs F | AFUA_5G00760, chs C | AFUA_2G01870, chs A | AFUA_1G12600, chs D | AFUA_3G14420, chs G | AFUA_2G13430, chs | AFUA_2G13440, chs E | 8 | ||

| Aspergillus niger CBS 513.88 | T01030 | ANI_1_316024, chs | ANI_1_2332024, chs | ANI_1_1542034, chs C | ANI_1_684064, chs C | ANI_1_1986074, chs D | ANI_1_252084, chs D | ANI_1_498084, chs B | ANI_1_1214104, chs C | ANI_1_120124, chs A | 9 | |

| Aspergillus nidulans FGSC A4 | T01016 | AN1555.2, CHS V (chs D) | AN2523.2, chs B | AN4367.2, hypothetical protein | AN4566.2, hypothetical protein | AN6317.2, hypothetical protein | AN6318.2, hypothetical protein | AN7032.2, hypothetical protein | 7 | |||

| Neurospora crassa | T01034 | NCU09324, chs 4 | NCU04352, chs 5 | NCU04350, chs 6 | NCU05268, chs 6; | NCU05239, chs A | NCU03611, chs 1 | NCU04251, chs 3 | 7 | |||

| Penicillium digitatum Pd1 | T04849 | PDIP_79230, chs E | PDIP_62350, hypothetical protein | PDIP_46630, chs G | PDIP_26990, chs D | PDIP_24450, chs G | PDIP_15450, chs B | PDIP_07640, chs A | PDIP_03360, chs F | 9 | ||

| Coccidioides immitis RS | T01114 | CIMG_05021, CHS V | CIMG_05598, chs C | CIMG_05647, chs G | CIMG_05022, chs 5 | CIMG_08766, chs 4 | CIMG_08655, chs 2 | CIMG_06862, CHS VI | 8 | |||

| Monascus purpureus HQ1 | TQB77221.1, CHS V | TQB75461.1, CHS III | TQB73913.1, CHS I | TQB72986.1, CHS VII | TQB70564.1, CHS II | TQB69157.1, CHS II | TQB73548.1, hypothetical protein | TQB73973.1, hypothetical protein | TQB73547.1, hypothetical protein | 9 | ||

| Monascus purpureus LQ-6 | monascus_02563, chs2 | monascus_02508, chs3 | monascus_05,161 chs 4 | monascus_05162, chs 6 | monascus_02870, chs activator | monascus_02765, chs 5 | monascus_02400, chs G | monascus_04382, chs A | 8 | |||

| Monascus purpureus M183 | g872, chs 2 | g920, chs F | g3077, chsE | g3078, chs | g2747, chs 3 | g5275, chs 3 | g4739, chs B | g5640, chs A | 8 | |||

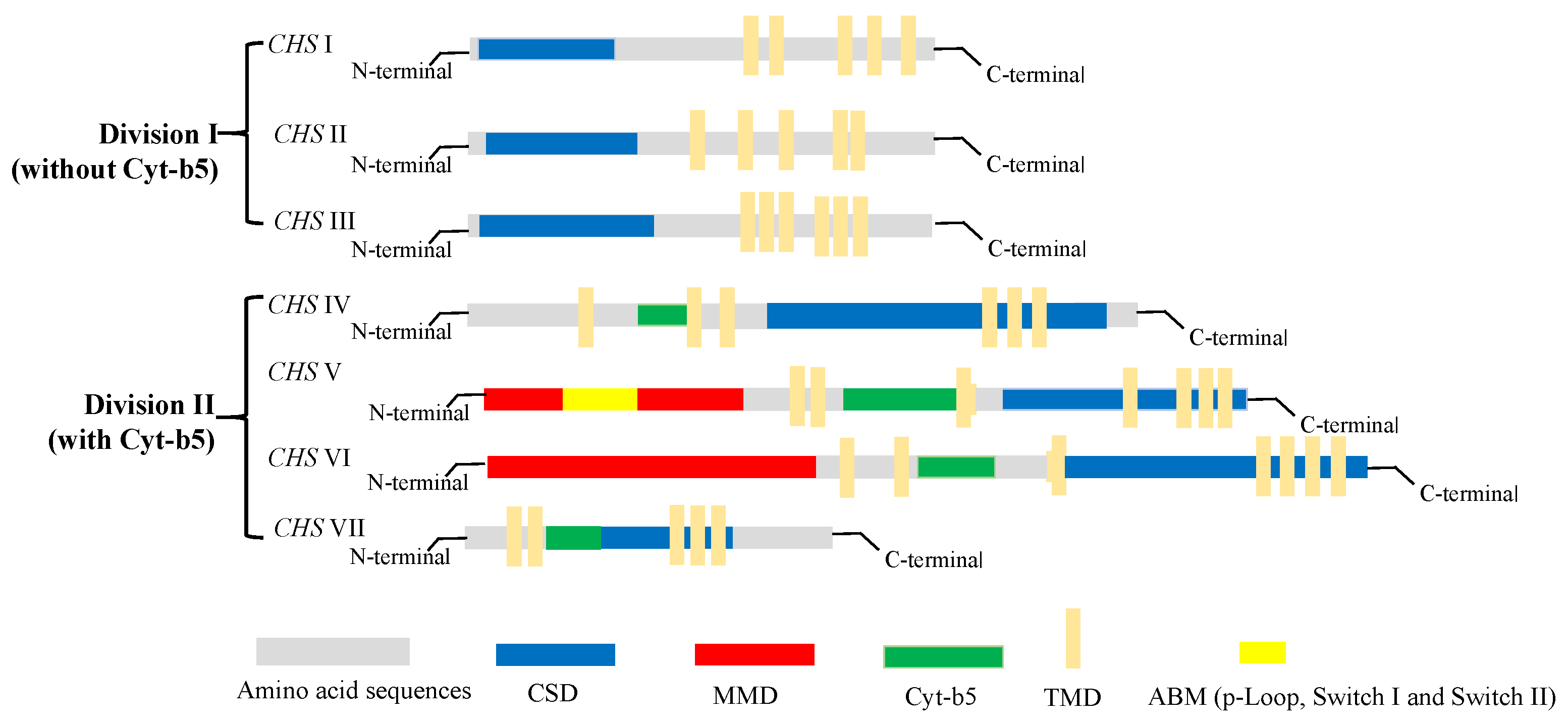

With the increasing accumulation of genomic sequence data for fungi in recent years, the number of identified chs genes in different species has reached approximately 200. However, most of these genes have yet to be fully characterized. Generally, chs enzymes are grouped into two divisions, division I (containing CHS I–III) and division II (containing CHS IV–VII) [18]. Among the members of the chs enzyme family (CHS I–VII), 6–10 chs genes identified in different fungi species encode proteins with discernable structural differences. As shown in Figure 3, there are obvious differences in the tertiary structures that distinguish the different classes of chs proteins. All chs members have multiple transmembrane domains (TMD); however, CHS IV–VII enzymes typically contain a cytochrome b5-like heme/steroid-binding domain (Cyt-b5), which is not found in classes I to III. Furthermore, CHS V and CHS VI proteins both have an N-terminal myosin motor domain (MMD) and a C-terminal chitin synthase domain (CSD) [19]. Although the structures of CHS V and CHS VI proteins are highly similar and difficult to differentiate, the MMD of CHS V proteins contains conserved ATP-binding motifs (ABM, including p-Loop, Switch I, and Switch II) absent in class VI chitin synthases [20]. In addition, CHS I–III proteins are characterized by hydrophobic C-terminal and hydrophilic N-terminal regions containing a catalytic domain. In our laboratory, the chs protein-encoding gene Monascus_05162, detected in the M. purpureus LQ-6 genome, was identified as a CHS VI class enzyme based on the tertiary structure of the protein and conserved domain analysis [21].

Figure 3. The structure and classification of members of the chitin synthase family.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jof9020205

References

- Klis, F.M.; Mol, P.; Hellingwerf, K.; Brul, S. Dynamics of cell wall structure in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2002, 26, 239–256.

- Kang, M.S.; Elango, N.; Mattia, E.; Au-Young, J.; Robbins, P.W.; Cabib, E. Isolation of chitin synthetase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Purification of an enzyme by entrapment in the reaction product. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 14966–14972.

- El Knidri, H.; Belaabed, R.; Addaou, A.; Laajeb, A.; Lahsini, A. Extraction, chemical modification and characterization of chitin and chitosan. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1181–1189.

- Moussian, B. Chitin: Structure, Chemistry and Biology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1142, 5–18.

- Hassainia, A.; Satha, H.; Boufi, S. Chitin from Agaricus bisporus: Extraction and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 117, 1334–1342.

- Jang, M.K.; Kong, B.G.; Jeong, Y.I.; Lee, C.H.; Nah, J.W. Physicochemical characterization of α-chitin,β-chitin, and γ-chitin separated from natural resources. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 3423–3432.

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632.

- Islam, S.; Bhuiyan, M.A.R.; Islam, M.N. Chitin and Chitosan: Structure, Properties and Applications in Biomedical Engineering. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 3, 854–866.

- Benchamas, G.; Huang, G.; Huang, S.; Huang, H. Preparation and biological activities of chitosan oligosaccharides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 107, 38–44.

- No, H.K.; Meyers, S.P. Application of chitosan for treatment of wastewaters. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2000, 163, 1–27.

- Gow, N.A.R.; Latge, J.P.; Munro, C.A.; Heitman, J. The Fungal Cell Wall: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 5.

- Yang, J.; Zhang, K.Q. Chitin Synthesis and Degradation in Fungi: Biology and Enzymes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1142, 153–167.

- Merzendorfer, H. The cellular basis of chitin synthesis in fungi and insects: Common principles and differences. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2011, 90, 759–769.

- Watanabe, H.; Azuma, M.; Igarashi, K.; Ooshima, H. Analysis of Chitin at the Hyphal Tip of Candida albicans Using Calcofluor White. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 1798–1801.

- Roncero, C. The genetic complexity of chitin synthesis in fungi. Curr. Genet. 2002, 41, 367–378.

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, H.; Du, Y.; Keyhani, N.O.; Xia, Y.; Jin, K. Members of chitin synthase family in Metarhizium acridum differentially affect fungal growth, stress tolerances, cell wall integrity and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007964.

- Munro, C.A.; Gow, N.A.R. Chitin synthesis in human pathogenic fungi. Med. Mycol. 2001, 39, 41–53.

- Larson, T.M.; Kendra, D.F.; Busman, M.; Brown, D.W. Fusarium verticillioides chitin synthases CHS5 and CHS7 are required for normal growth and pathogenicity. Curr. Genet. 2011, 57, 177–189.

- Cui, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lei, N.; Wang, K.; Zhu, T. Botrytis cinerea chitin synthase BcChsVI is required for normal growth and pathogenicity. Curr. Genet. 2013, 59, 119–128.

- Takeshita, N.; Yamashita, S.; Ohta, A.; Horiuchi, H. Aspergillus nidulans class V and VI chitin synthases CsmA and CsmB, each with a myosin motor-like domain, perform compensatory functions that are essential for hyphal tip growth. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 59, 1380–1394.

- Shu, M.; Lu, P.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.; Gong, Z.; Cai, X.; Zhou, B.; Lin, Q.; Liu, J. Disruption of the Chitin Biosynthetic Pathway Results in Significant Changes in the Cell Growth Phenotypes and Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites of Monascus purpureus. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 910.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!