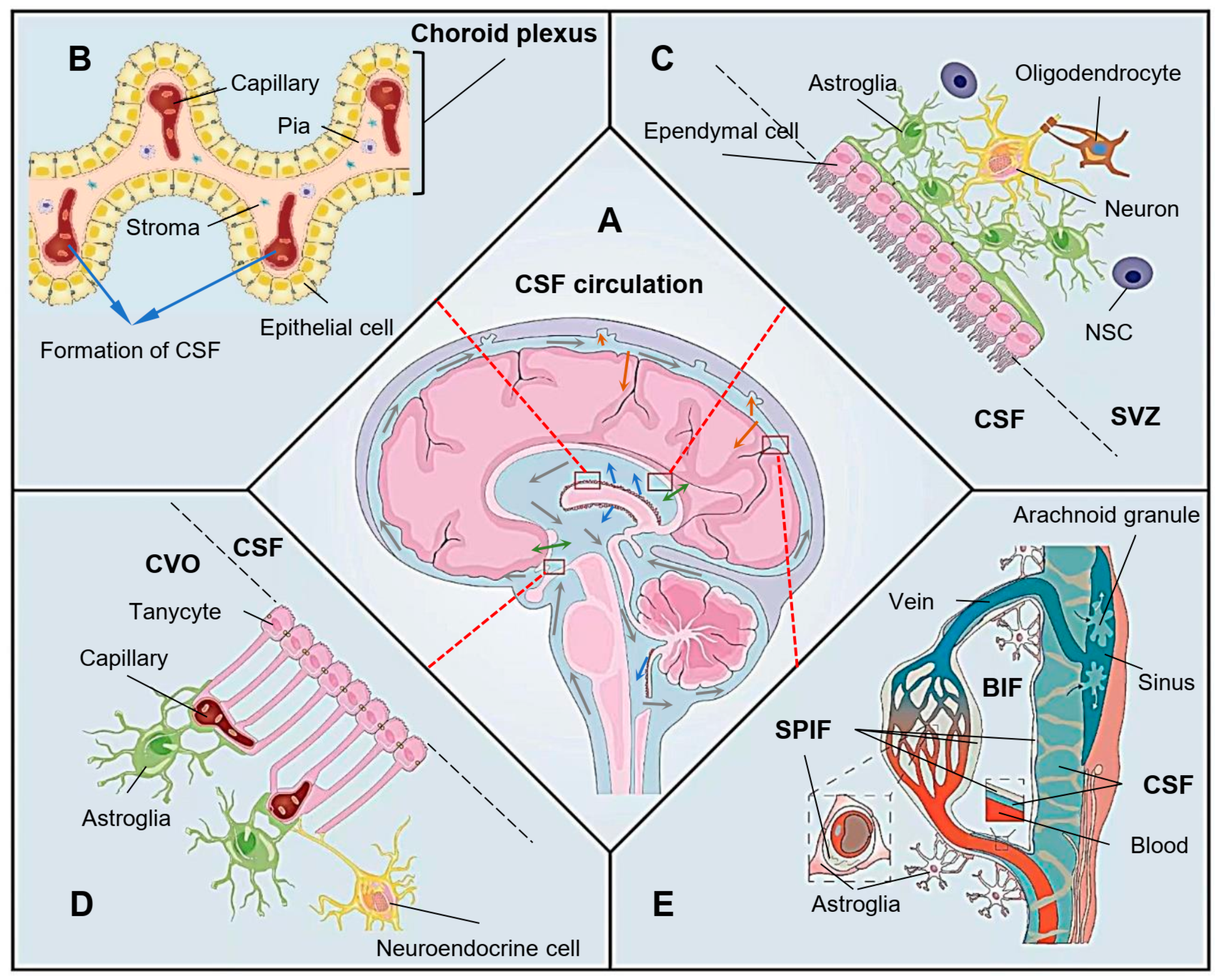

The neuron loss caused by the progressive damage to the nervous system is proposed to be the main pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Ependyma is a layer of ciliated ependymal cells that participates in the formation of the brain-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCB). However, as the protective barrier lining the brain ventricles, the ependyma is extremely vulnerable to cytotoxic and cytolytic immune responses. When the ependyma is damaged, the integrity of BCB is destroyed, and the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)flow and material exchange is affected, leading to brain microenvironment imbalance, which plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases.

- neurodegenerative diseases

- radiation-induced brain injury

- ependyma

1. The Physiological Function of Ependyma

2. Ependymal Dysfunctions in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biom13050754

References

- Zhang, J.; Chandrasekaran, G.; Li, W.; Kim, D.Y.; Jeong, I.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Liang, T.; Bae, J.Y.; Choi, I.; Kang, H.; et al. Wnt-PLC-IP(3)-Connexin-Ca(2+) axis maintains ependymal motile cilia in zebrafish spinal cord. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1860.

- Lim, D.A.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. The Adult Ventricular-Subventricular Zone (V-SVZ) and Olfactory Bulb (OB) Neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a018820.

- Luo, Y.; Coskun, V.; Liang, A.; Yu, J.; Cheng, L.; Ge, W.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, K.; Li, C.; Cui, Y.; et al. Single-cell transcriptome analyses reveal signals to activate dormant neural stem cells. Cell 2015, 161, 1175–1186.

- Shah, P.T.; Stratton, J.A.; Stykel, M.G.; Abbasi, S.; Sharma, S.; Mayr, K.A.; Koblinger, K.; Whelan, P.J.; Biernaskie, J. Single-Cell Transcriptomics and Fate Mapping of Ependymal Cells Reveals an Absence of Neural Stem Cell Function. Cell 2018, 173, 1045–1057.e9.

- Ren, Y.; Ao, Y.; O’Shea, T.M.; Burda, J.E.; Bernstein, A.M.; Brumm, A.J.; Muthusamy, N.; Ghashghaei, H.T.; Carmichael, S.T.; Cheng, L.; et al. Ependymal cell contribution to scar formation after spinal cord injury is minimal, local and dependent on direct ependymal injury. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41122.

- Spassky, N.; Merkle, F.T.; Flames, N.; Tramontin, A.D.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Adult ependymal cells are postmitotic and are derived from radial glial cells during embryogenesis. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 10–18.

- Louvi, A.; Grove, E.A. Cilia in the CNS: The quiet organelle claims center stage. Neuron 2011, 69, 1046–1060.

- Mirzadeh, Z.; Kusne, Y.; Duran-Moreno, M.; Cabrales, E.; Gil-Perotin, S.; Ortiz, C.; Chen, B.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Sanai, N.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Bi- and uniciliated ependymal cells define continuous floor-plate-derived tanycytic territories. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 13759.

- Roales-Bujan, R.; Paez, P.; Guerra, M.; Rodriguez, S.; Vio, K.; Ho-Plagaro, A.; Garcia-Bonilla, M.; Rodriguez-Perez, L.M.; Dominguez-Pinos, M.D.; Rodriguez, E.M.; et al. Astrocytes acquire morphological and functional characteristics of ependymal cells following disruption of ependyma in hydrocephalus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012, 124, 531–546.

- Municio, C.; Carrero, L.; Antequera, D.; Carro, E. Choroid Plexus Aquaporins in CSF Homeostasis and the Glymphatic System: Their Relevance for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 878.

- Bethlehem, R.A.I.; Seidlitz, J.; White, S.R.; Vogel, J.W.; Anderson, K.M.; Adamson, C.; Adler, S.; Alexopoulos, G.S.; Anagnostou, E.; Areces-Gonzalez, A.; et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature 2022, 604, 525–533.

- Del Bigio, M.R. Ependymal cells: Biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 55–73.

- Johanson, C.; Stopa, E.; McMillan, P.; Roth, D.; Funk, J.; Krinke, G. The distributional nexus of choroid plexus to cerebrospinal fluid, ependyma and brain: Toxicologic/pathologic phenomena, periventricular destabilization, and lesion spread. Toxicol. Pathol. 2011, 39, 186–212.

- Gross, P.M.; Weindl, A. Peering through the windows of the brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1987, 7, 663–672.

- Langlet, F.; Mullier, A.; Bouret, S.G.; Prevot, V.; Dehouck, B. Tanycyte-like cells form a blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier in the circumventricular organs of the mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013, 521, 3389–3405.

- Bolborea, M.; Langlet, F. What is the physiological role of hypothalamic tanycytes in metabolism? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2021, 320, R994–R1003.

- Takemura, S.; Isonishi, A.; Horii-Hayashi, N.; Tanaka, T.; Tatsumi, K.; Komori, T.; Yamamuro, K.; Yamano, M.; Nishi, M.; Makinodan, M.; et al. Juvenile social isolation affects the structure of the tanycyte-vascular interface in the hypophyseal portal system of the adult mice. Neurochem. Int. 2023, 162, 105439.

- Mullier, A.; Bouret, S.G.; Prevot, V.; Dehouck, B. Differential distribution of tight junction proteins suggests a role for tanycytes in blood-hypothalamus barrier regulation in the adult mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 943–962.

- Langlet, F.; Levin, B.E.; Luquet, S.; Mazzone, M.; Messina, A.; Dunn-Meynell, A.A.; Balland, E.; Lacombe, A.; Mazur, D.; Carmeliet, P.; et al. Tanycytic VEGF-A boosts blood-hypothalamus barrier plasticity and access of metabolic signals to the arcuate nucleus in response to fasting. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 607–617.

- Miyata, S. Glial functions in the blood-brain communication at the circumventricular organs. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 991779.

- Geller, S.; Arribat, Y.; Netzahualcoyotzi, C.; Lagarrigue, S.; Carneiro, L.; Zhang, L.; Amati, F.; Lopez-Mejia, I.C.; Pellerin, L. Tanycytes Regulate Lipid Homeostasis by Sensing Free Fatty Acids and Signaling to Key Hypothalamic Neuronal Populations via FGF21 Secretion. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 833–844.e7.

- Bentivoglio, M.; Kristensson, K.; Rottenberg, M.E. Circumventricular Organs and Parasite Neurotropism: Neglected Gates to the Brain? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2877.

- Adigun, O.O.; Al-Dhahir, M.A. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Cerebrospinal Fluid. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Weller, R.O.; Sharp, M.M.; Christodoulides, M.; Carare, R.O.; Mollgard, K. The meninges as barriers and facilitators for the movement of fluid, cells and pathogens related to the rodent and human CNS. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 363–385.

- Rasmussen, M.K.; Mestre, H.; Nedergaard, M. Fluid transport in the brain. Physiol. Rev. 2022, 102, 1025–1151.

- Mestre, H.; Verma, N.; Greene, T.D.; Lin, L.A.; Ladron-de-Guevara, A.; Sweeney, A.M.; Liu, G.; Thomas, V.K.; Galloway, C.A.; de Mesy Bentley, K.L.; et al. Periarteriolar spaces modulate cerebrospinal fluid transport into brain and demonstrate altered morphology in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3897.

- Shah, T.; Leurgans, S.E.; Mehta, R.I.; Yang, J.; Galloway, C.A.; de Mesy Bentley, K.L.; Schneider, J.A.; Mehta, R.I. Arachnoid granulations are lymphatic conduits that communicate with bone marrow and dura-arachnoid stroma. J. Exp. Med. 2023, 220, e20220618.

- Mollgard, K.; Beinlich, F.R.M.; Kusk, P.; Miyakoshi, L.M.; Delle, C.; Pla, V.; Hauglund, N.L.; Esmail, T.; Rasmussen, M.K.; Gomolka, R.S.; et al. A mesothelium divides the subarachnoid space into functional compartments. Science 2023, 379, 84–88.

- Bissenas, A.; Fleeting, C.; Patel, D.; Al-Bahou, R.; Patel, A.; Nguyen, A.; Woolridge, M.; Angelle, C.; Lucke-Wold, B. CSF Dynamics: Implications for Hydrocephalus and Glymphatic Clearance. Curr. Res. Med. Sci. 2022, 1, 24–42.

- Xie, L.; Kang, H.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.J.; Liao, Y.; Thiyagarajan, M.; O’Donnell, J.; Christensen, D.J.; Nicholson, C.; Iliff, J.J.; et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 2013, 342, 373–377.

- Shook, B.A.; Lennington, J.B.; Acabchuk, R.L.; Halling, M.; Sun, Y.; Peters, J.; Wu, Q.; Mahajan, A.; Fellows, D.W.; Conover, J.C. Ventriculomegaly associated with ependymal gliosis and declines in barrier integrity in the aging human and mouse brain. Aging Cell 2014, 13, 340–350.

- Aspelund, A.; Antila, S.; Proulx, S.T.; Karlsen, T.V.; Karaman, S.; Detmar, M.; Wiig, H.; Alitalo, K. A dural lymphatic vascular system that drains brain interstitial fluid and macromolecules. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 991–999.

- Ahn, J.H.; Cho, H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Ham, J.S.; Park, I.; Suh, S.H.; Hong, S.P.; Song, J.H.; Hong, Y.K.; et al. Meningeal lymphatic vessels at the skull base drain cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 2019, 572, 62–66.

- Hannocks, M.J.; Pizzo, M.E.; Huppert, J.; Deshpande, T.; Abbott, N.J.; Thorne, R.G.; Sorokin, L. Molecular characterization of perivascular drainage pathways in the murine brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 669–686.

- Toledo, J.B.; Arnold, S.E.; Raible, K.; Brettschneider, J.; Xie, S.X.; Grossman, M.; Monsell, S.E.; Kukull, W.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre. Brain 2013, 136, 2697–2706.

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111.

- Thomas, J.H. Theoretical analysis of wake/sleep changes in brain solute transport suggests a flow of interstitial fluid. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 30.

- Jackson, R.J.; Meltzer, J.C.; Nguyen, H.; Commins, C.; Bennett, R.E.; Hudry, E.; Hyman, B.T. APOE4 derived from astrocytes leads to blood-brain barrier impairment. Brain 2022, 145, 3582–3593.

- Blanchard, J.W.; Akay, L.A.; Davila-Velderrain, J.; von Maydell, D.; Mathys, H.; Davidson, S.M.; Effenberger, A.; Chen, C.Y.; Maner-Smith, K.; Hajjar, I.; et al. APOE4 impairs myelination via cholesterol dysregulation in oligodendrocytes. Nature 2022, 611, 769–779.

- Guttenplan, K.A.; Weigel, M.K.; Prakash, P.; Wijewardhane, P.R.; Hasel, P.; Rufen-Blanchette, U.; Munch, A.E.; Blum, J.A.; Fine, J.; Neal, M.C.; et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes induce cell death via saturated lipids. Nature 2021, 599, 102–107.

- Kim, S.; Kim, N.; Park, S.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, J.; Yoo, S.J.; Lee, J.W.; Moon, C.; Yu, S.W.; Kim, E.K. Tanycytic TSPO inhibition induces lipophagy to regulate lipid metabolism and improve energy balance. Autophagy 2020, 16, 1200–1220.

- Muthusamy, N.; Sommerville, L.J.; Moeser, A.J.; Stumpo, D.J.; Sannes, P.; Adler, K.; Blackshear, P.J.; Weimer, J.M.; Ghashghaei, H.T. MARCKS-dependent mucin clearance and lipid metabolism in ependymal cells are required for maintenance of forebrain homeostasis during aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 764–773.

- Muthusamy, N.; Williams, T.I.; O’Toole, R.; Brudvig, J.J.; Adler, K.B.; Weimer, J.M.; Muddiman, D.C.; Ghashghaei, H.T. Phosphorylation-dependent proteome of Marcks in ependyma during aging and behavioral homeostasis in the mouse forebrain. Geroscience 2022, 44, 2077–2094.

- Del Carmen Gomez-Roldan, M.; Perez-Martin, M.; Capilla-Gonzalez, V.; Cifuentes, M.; Perez, J.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Fernandez-Llebrez, P. Neuroblast proliferation on the surface of the adult rat striatal wall after focal ependymal loss by intracerebroventricular injection of neuraminidase. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 507, 1571–1587.

- Luo, J.; Shook, B.A.; Daniels, S.B.; Conover, J.C. Subventricular zone-mediated ependyma repair in the adult mammalian brain. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 3804–3813.

- Garcia-Bonilla, M.; Castaneyra-Ruiz, L.; Zwick, S.; Talcott, M.; Otun, A.; Isaacs, A.M.; Morales, D.M.; Limbrick, D.D., Jr.; McAllister, J.P., 2nd. Acquired hydrocephalus is associated with neuroinflammation, progenitor loss, and cellular changes in the subventricular zone and periventricular white matter. Fluids Barriers CNS 2022, 19, 17.

- Piehl, N.; van Olst, L.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Teregulova, V.; Simonton, B.; Zhang, Z.; Tapp, E.; Channappa, D.; Oh, H.; Losada, P.M.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid immune dysregulation during healthy brain aging and cognitive impairment. Cell 2022, 185, 5028–5039.e13.

- Sofroniew, M.V. Molecular dissection of reactive astrogliosis and glial scar formation. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 638–647.

- Haj-Yasein, N.N.; Vindedal, G.F.; Eilert-Olsen, M.; Gundersen, G.A.; Skare, O.; Laake, P.; Klungland, A.; Thoren, A.E.; Burkhardt, J.M.; Ottersen, O.P.; et al. Glial-conditional deletion of aquaporin-4 (Aqp4) reduces blood-brain water uptake and confers barrier function on perivascular astrocyte endfeet. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17815–17820.

- Abbott, N.J.; Pizzo, M.E.; Preston, J.E.; Janigro, D.; Thorne, R.G. The role of brain barriers in fluid movement in the CNS: Is there a ‘glymphatic’ system? Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 387–407.

- Long, C.Y.; Huang, G.Q.; Du, Q.; Zhou, L.Q.; Zhou, J.H. The dynamic expression of aquaporins 1 and 4 in rats with hydrocephalus induced by subarachnoid haemorrhage. Folia Neuropathol. 2019, 57, 182–195.

- Bigotte, M.; Gimenez, M.; Gavoille, A.; Deligiannopoulou, A.; El Hajj, A.; Croze, S.; Goumaidi, A.; Malleret, G.; Salin, P.; Giraudon, P.; et al. Ependyma: A new target for autoantibodies in neuromyelitis optica? Brain Commun. 2022, 4, fcac307.

- Sun, X.; Tian, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Hou, B.; Xie, A. Association of AQP4 single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs335929 and rs2075575) with Parkinson’s disease: A case-control study. Neurosci. Lett. 2023, 797, 137062.

- Zappaterra, M.W.; Lehtinen, M.K. The cerebrospinal fluid: Regulator of neurogenesis, behavior, and beyond. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 2863–2878.

- Jimenez, A.J.; Dominguez-Pinos, M.D.; Guerra, M.M.; Fernandez-Llebrez, P.; Perez-Figares, J.M. Structure and function of the ependymal barrier and diseases associated with ependyma disruption. Tissue Barriers 2014, 2, e28426.

- Mirzadeh, Z.; Han, Y.G.; Soriano-Navarro, M.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Cilia organize ependymal planar polarity. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 2600–2610.

- Wallingford, J.B. Planar cell polarity signaling, cilia and polarized ciliary beating. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010, 22, 597–604.

- Kishimoto, N.; Sawamoto, K. Planar polarity of ependymal cilia. Differentiation 2012, 83, S86–S90.

- Butler, M.T.; Wallingford, J.B. Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 375–388.

- Lucas, J.S.; Davis, S.D.; Omran, H.; Shoemark, A. Primary ciliary dyskinesia in the genomics age. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 202–216.

- Mitchison, H.M.; Valente, E.M. Motile and non-motile cilia in human pathology: From function to phenotypes. J. Pathol. 2017, 241, 294–309.

- Reiter, J.F.; Leroux, M.R. Genes and molecular pathways underpinning ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 533–547.

- Zhang, J.; Williams, M.A.; Rigamonti, D. Genetics of human hydrocephalus. J. Neurol. 2006, 253, 1255–1266.

- Palha, J.A.; Santos, N.C.; Marques, F.; Sousa, J.; Bessa, J.; Miguelote, R.; Sousa, N.; Belmonte-de-Abreu, P. Do genes and environment meet to regulate cerebrospinal fluid dynamics? Relevance for schizophrenia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2012, 6, 31.

- Ohata, S.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Planar Organization of Multiciliated Ependymal (E1) Cells in the Brain Ventricular Epithelium. Trends Neurosci. 2016, 39, 543–551.

- Ohata, S.; Nakatani, J.; Herranz-Perez, V.; Cheng, J.; Belinson, H.; Inubushi, T.; Snider, W.D.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Alvarez-Buylla, A. Loss of Dishevelleds disrupts planar polarity in ependymal motile cilia and results in hydrocephalus. Neuron 2014, 83, 558–571.

- Muller-Schmitz, K.; Krasavina-Loka, N.; Yardimci, T.; Lipka, T.; Kolman, A.G.J.; Robbers, S.; Menge, T.; Kujovic, M.; Seitz, R.J. Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2020, 88, 703–711.

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 32.

- Rice, L.; Bisdas, S. The diagnostic value of FDG and amyloid PET in Alzheimer’s disease-A systematic review. Eur. J. Radiol. 2017, 94, 16–24.

- Koepsell, H. Glucose transporters in brain in health and disease. Pflug. Arch. 2020, 472, 1299–1343.

- An, Y.; Varma, V.R.; Varma, S.; Casanova, R.; Dammer, E.; Pletnikova, O.; Chia, C.W.; Egan, J.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Troncoso, J.; et al. Evidence for brain glucose dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018, 14, 318–329.

- Aldhshan, M.S.; Jhanji, G.; Mizuno, T.M. Glucose and fructose directly stimulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene expression in microglia. Neuroreport 2022, 33, 583–589.

- Franke, T.N.; Irwin, C.; Bayer, T.A.; Brenner, W.; Beindorff, N.; Bouter, C.; Bouter, Y. In vivo Imaging with (18)F-FDG- and (18)F-Florbetaben-PET/MRI Detects Pathological Changes in the Brain of the Commonly Used 5XFAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 529.

- Ohm, D.T.; Fought, A.J.; Martersteck, A.; Coventry, C.; Sridhar, J.; Gefen, T.; Weintraub, S.; Bigio, E.; Mesulam, M.M.; Rogalski, E.; et al. Accumulation of neurofibrillary tangles and activated microglia is associated with lower neuron densities in the aphasic variant of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol. 2021, 31, 189–204.

- Zeng, H.; Huang, J.; Zhou, H.; Meilandt, W.J.; Dejanovic, B.; Zhou, Y.; Bohlen, C.J.; Lee, S.H.; Ren, J.; Liu, A.; et al. Integrative in situ mapping of single-cell transcriptional states and tissue histopathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 430–446.

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Capuano, A.W.; Leurgans, S.E.; Bennett, D.A.; Schneider, J.A. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: A cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 934–943.

- Arbel-Ornath, M.; Hudry, E.; Eikermann-Haerter, K.; Hou, S.; Gregory, J.L.; Zhao, L.; Betensky, R.A.; Frosch, M.P.; Greenberg, S.M.; Bacskai, B.J. Interstitial fluid drainage is impaired in ischemic stroke and Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 126, 353–364.

- Drieu, A.; Du, S.; Storck, S.E.; Rustenhoven, J.; Papadopoulos, Z.; Dykstra, T.; Zhong, F.; Kim, K.; Blackburn, S.; Mamuladze, T.; et al. Parenchymal border macrophages regulate the flow dynamics of the cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 2022, 611, 585–593.

- Mollenhauer, B.; Caspell-Garcia, C.J.; Coffey, C.S.; Taylor, P.; Shaw, L.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Singleton, A.; Frasier, M.; Marek, K.; Galasko, D.; et al. Longitudinal CSF biomarkers in patients with early Parkinson disease and healthy controls. Neurology 2017, 89, 1959–1969.

- Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Marshall, C.; Wu, T.; Hu, G.; Xiao, M. Aquaporin 4 deletion exacerbates brain impairments in a mouse model of chronic sleep disruption. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2020, 26, 228–239.

- Tobaldini, E.; Costantino, G.; Solbiati, M.; Cogliati, C.; Kara, T.; Nobili, L.; Montano, N. Sleep, sleep deprivation, autonomic nervous system and cardiovascular diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74, 321–329.

- Musiek, E.S.; Holtzman, D.M. Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration. Science 2016, 354, 1004–1008.

- Koinis-Mitchell, D.; Rosario-Matos, N.; Ramirez, R.R.; Garcia, P.; Canino, G.J.; Ortega, A.N. Sleep, Depressive/Anxiety Disorders, and Obesity in Puerto Rican Youth. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2017, 24, 59–73.

- Walker, F.O. Huntington’s disease. Lancet 2007, 369, 218–228.

- Tabrizi, S.J.; Ghosh, R.; Leavitt, B.R. Huntingtin Lowering Strategies for Disease Modification in Huntington’s Disease. Neuron 2019, 102, 899.

- Mead, R.J.; Shan, N.; Reiser, H.J.; Marshall, F.; Shaw, P.J. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A neurodegenerative disorder poised for successful therapeutic translation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 185–212.

- Boillee, S.; Vande Velde, C.; Cleveland, D.W. ALS: A disease of motor neurons and their nonneuronal neighbors. Neuron 2006, 52, 39–59.

- Ramos-Campoy, O.; Avila-Polo, R.; Grau-Rivera, O.; Antonell, A.; Clarimon, J.; Rojas-Garcia, R.; Charif, S.; Santiago-Valera, V.; Hernandez, I.; Aguilar, M.; et al. Systematic Screening of Ubiquitin/p62 Aggregates in Cerebellar Cortex Expands the Neuropathological Phenotype of the C9orf72 Expansion Mutation. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 77, 703–709.

- Kim, J.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.; Curtis, M.A.; Nicholson, L.F. The RAGE receptor and its ligands are highly expressed in astrocytes in a grade-dependant manner in the striatum and subependymal layer in Huntington’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2015, 134, 927–942.

- Sun, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Qian, Y. IL-17A is implicated in lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment in aged rats via microglial activation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2015, 12, 165.

- Yamanaka, D.; Kawano, T.; Nishigaki, A.; Aoyama, B.; Tateiwa, H.; Shigematsu-Locatelli, M.; Locatelli, F.M.; Yokoyama, M. Preventive effects of dexmedetomidine on the development of cognitive dysfunction following systemic inflammation in aged rats. J. Anesth. 2017, 31, 25–35.

- Ochaba, J.; Fote, G.; Kachemov, M.; Thein, S.; Yeung, S.Y.; Lau, A.L.; Hernandez, S.; Lim, R.G.; Casale, M.; Neel, M.J.; et al. IKKbeta slows Huntington’s disease progression in R6/1 mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10952–10961.

- Ruiz, F.; Vigne, S.; Pot, C. Resolution of inflammation during multiple sclerosis. Semin. Immunopathol. 2019, 41, 711–726.

- Toth, P.; Tarantini, S.; Csiszar, A.; Ungvari, Z. Functional vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: Mechanisms and consequences of cerebral autoregulatory dysfunction, endothelial impairment, and neurovascular uncoupling in aging. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2017, 312, H1–H20.

- Tarantini, S.; Tran, C.H.T.; Gordon, G.R.; Ungvari, Z.; Csiszar, A. Impaired neurovascular coupling in aging and Alzheimer’s disease: Contribution of astrocyte dysfunction and endothelial impairment to cognitive decline. Exp. Gerontol. 2017, 94, 52–58.

- Sumbria, R.K.; Grigoryan, M.M.; Vasilevko, V.; Paganini-Hill, A.; Kilday, K.; Kim, R.; Cribbs, D.H.; Fisher, M.J. Aging exacerbates development of cerebral microbleeds in a mouse model. J. Neuroinflamm. 2018, 15, 69.

- Zang, L.; Yang, B.; Zhang, M.; Cui, J.; Ma, X.; Wei, L. Trelagliptin Mitigates Macrophage Infiltration by Preventing the Breakdown of the Blood-Brain Barrier in the Brain of Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion Mice. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2021, 34, 1016–1023.

- Xiang, P.; Chew, W.S.; Seow, W.L.; Lam, B.W.S.; Ong, W.Y.; Herr, D.R. The S1P(2) receptor regulates blood-brain barrier integrity and leukocyte extravasation with implications for neurodegenerative disease. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 146, 105018.

- Vila Verde, D.; de Curtis, M.; Librizzi, L. Seizure-Induced Acute Glial Activation in the in vitro Isolated Guinea Pig Brain. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 607603.

- Towner, R.A.; Saunders, D.; Smith, N.; Gulej, R.; McKenzie, T.; Lawrence, B.; Morton, K.A. Anti-inflammatory agent, OKN-007, reverses long-term neuroinflammatory responses in a rat encephalopathy model as assessed by multi-parametric MRI: Implications for aging-associated neuroinflammation. Geroscience 2019, 41, 483–494.