Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Licorice, a natural medicine derived from the roots and rhizomes of Glycyrrhiza species, possesses a wide range of therapeutic applications, including antiviral properties. Glycyrrhizic acid (GL) and glycyrrhetinic acid (GA) are the most important active ingredients in licorice. Glycyrrhetinic acid 3-O-mono-β-d-glucuronide (GAMG) is the active metabolite of GL. GL and its metabolites have a wide range of antiviral activities against viruses, such as, the hepatitis virus, herpes virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and so on.

- glycyrrhizic acid

- GAMG

- glycyrrhetinic acid

- antiviral

- SARS-CoV-2

1. Introduction

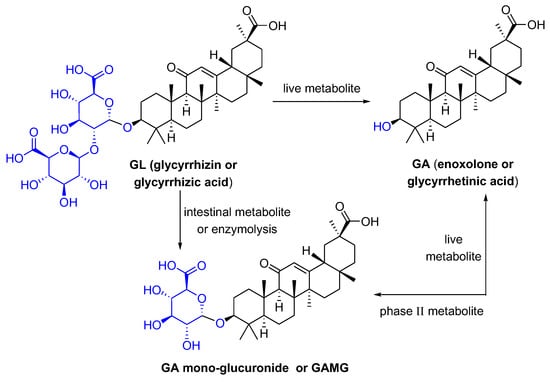

Glycyrrhizic acid (GL), a tetracyclic triterpenoid saponin, has a broad spectrum of biological activities [1], especially antiviral effects [2]. As shown in Figure 1, GL is composed of two molecules of glucuronic acid and one molecule of glycyrrhetinic acid (GA). GA, the aglycone of GL, is one of the active metabolites of GL under the action of gut commensal bacteria. GA is also one of active ingredients in licorice, and possesses extensive pharmacological activities such as anti-inflammatory [3], antioxidative [4], and antiviral effects [5]. GL can be metabolized in the intestine or be transformed via enzymolysis to glycyrrhetinic acid 3-O-mono-β-d-glucuronide (GAMG). GAMG, a distal glucuronic acid hydrolysate of GL, has a higher bioavailability and stronger physiological functions than GL, including antitumor, antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities [6][7]. In particular, GL and its metabolites have antiviral infection properties and improve symptoms caused by viral infections.

Figure 1. The structures of GL and its metabolites GA and GAMG.

Viruses usually include plant viruses, animal viruses and bacterial viruses. It is an organism with a special structure, usually containing only DNA or RNA, and parasitic in living cells, multiplying by self-replication. However, many viruses have a strong ability to invade, destroy, and even endanger the health of humans, animals, and plants. For example, the new SARS-CoV-2 virus that broke out in 2019 has been an ever-present threat to public health worldwide, and has already resulted in millions of dead. The constant mutation of the virus has brought great difficulties to epidemic prevention and people’s treatment. In addition, there are many common viruses in daily life, such as hepatitis viruses, influenza viruses, and herpesviruses.

Viral proliferation is a complex process, and the antiviral effect of natural products may influence the entry (attachment, penetration, intracellular trafficking, and uncoating), gene replication, and exit (assembly and maturation, and release) [8]. The antiviral mechanism of GL and its metabolites was not fully clear. Research reports indicated that GL can inhibit viral replication [5], regulate the fluidity of the plasma membrane, and affect the virus’s function of entering the cell and stabilizing the membrane [9][10]. For instance, acute or chronic hepatitis patients with elevated alanine aminotransferase were effectively treated with diammonium glycyrrhizinate enteric-coated capsules and diammonium glycyrrhizinate injections. GL can significantly reduce steatosis and necrosis of liver cells [11][12], inhibit liver fibrosis and inflammation, and promote cell regeneration. These also have been widely used as new inhibitors of the human immunodeficiency virus [13], Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [14], SARS-related coronavirus [15] and Zika virus [16][17]. The bibliometric analysis showed that GL is most widely studied for antiviral in licorice [16][18]. GL may be a natural candidate for the treatment of the SARS-CoV-2 infection, as it has been reported to bind to multiple proteins of the virus, including the S protein, 3CLpro, angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), etc. [19]. GL and GA greatly reduced inflammation through the interferon (IFN-γ), which meant that GL and GA have very important antiviral properties [20].

2. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Activity

In 2019, the Coronaviruse disease (COVID-19) broke out, caused large-scale human infection worldwide, and brought serious health hazards and economic losses. So far, the virus has continued to mutate and spread, and it is still seriously endangering human health and safety. At present, the SARS-CoV-2 infection cannot be effectively inhibited after vaccination, and there is no effective drug for the treatment of the viral infection in clinical practice. It was previously reported that ACE2 was proven to be an important and special receptor for the SARS coronavirus [21]. Recent research showed that the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 was specific for the human ACE-2 receptor, so the human ACE2 receptor acted as an important mediator of the SARS-CoV-2 infection [22][23].

SARS-CoV-2 is a β-coronavirus which contains three transmembrane proteins, spike protein (S), membrane protein (M), and envelope protein (E). SARS-CoV-2 also contains a large nucleoprotein (N) enveloped positive RNA genome [24]. GA has a good affinity for the spike protein (S) and master protease (Mpro) receptors of SARS-CoV-2 [25]. Since SARS-CoV-2 has an impact on multiple organs by attaching to the ACE2 receptor, patients may suffer obesity, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases, renal diseases, gastro-intestinal diseases and neurological diseases [26]. COVID-19 is the subject of intense research, with potential therapeutic drugs in various stages of testing, and with as many new therapeutic targets being investigated, such as the SSAA09E2 and CP-1 peptide that interfere with ACE2 recognition, and camostat and nafamostat that inhibit the type 2 transmembrane serine protease (TMPRSS2) [27]. Crucially, virion enters into target cells through the ACE2 receptor binding to a highly glycosylated spike protein trimer. Recently, GL was reported to have the ability to bind to ACE2, which can prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Virtual screening also revealed that GL is effective against the target proteins of SARS-CoV-2 [28], serves a potential inhibitor of the ACE2-specific receptor binding domain (RBD) on the spike glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2 [29][30], or prevents SARS-CoV-2 from entering the host cells [31]. Further, GL can directly bind to the site of the SARS-CoV-2 spike interaction, interfere with spike ACE2 action, thus blocking binding and fusion events in the virus life cycle [32]. Additionally, GL interacts with the S protein and achieves the antiviral activity through mediating cell attachment and entry of SARS-CoV-2, blocking S-mediated cell binding [33]. The silicon docking research also proved the above views that GL and GA can directly interact with the ACE2, spike protein, TMPRSS2, and 3-chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease, key players in viral internalization and replication [34]. In vitro experiments have shown that GL is the most potent and non-toxic broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus molecule due to the disrupted interaction of the S-RBD and ACE2 by GL.

The various pharmacological activities of GL and its derivatives were summarized, and the structurally modified GL-related derivatives were further developed to make them less cytotoxic and more targeted [35]. Moreover, the interaction between GL and the envelope protein was revealed to be an effective inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein at the molecular and structural levels [36]. In summarizing these studies, the researchers can think that the inhibitory effects of GL on SARS-CoV-2 are through the following three aspects. Firstly, GL prevents virus replication and spread by interacting with ACE2, the potential receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Secondly, GL directly interacts with the spike protein on the SARS-CoV-2 envelope, thereby blocking binding and fusion events in the viral life cycle. Thirdly, GL acts as a potential envelope protein inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2, disrupting the function and structure of the virus.

The RBD in the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein may be a potential drug target that plays a variety of key functions in the life cycle of the virus, especially viral replication. GL showed a higher binding affinity with target proteins, which may help block the important site within the RNA binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 viral nucleocapsid protein (N) and reduce the risk of infection in the host [37]. Viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) remains the preferred target for COVID-19 prevention or treatment, and nucleoside analogues are the most promising RdRp inhibitors, with the limitation that nucleoside analogues can be removed by SARS-CoV-2 exonuclease (ExoN). GL has been identified as a potential RdRp inhibitor with ExoN activity, contributing to better antiviral effects [38].

In addition, virtual screening showed that GL had the best affinity towards key proteases of SARS-CoV-2, which played a pivotal role in mediating viral replication and transcription [31][39]. It had been reported that GL and GA potentially inhibited SARS-CoV-2 infection, while revealing that the target of GL was the nsp7 protein, and GA binds to the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 [40]. There are various reports on the antiviral mechanism of GL and its derivatives, but most studies focus on ACE2. Murch pointed out that GL and its metabolites directly inhibited of expression of TMPRSS2, which is related to virus entry, then reduced the expression of ACE2 [18].

From a pharmacological point of view, GL showed therapeutic potential for COVID-19 through binding to ACE2, down-regulating proinflammatory cytokines, inhibiting intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, suppressing high respiratory tract output, and inducing endogenous interferons [41]. The anti-inflammatory activity of GL may play a crucial role in the excessive inflammatory response after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Network analysis and protein-protein interactions showed that the GL’s key targets for COVID-19 may include the intercellular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9), toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), and the inflammatory cytokine signals, growth factor receptor signaling, and complement system were the crucial pathways by pathway enrichment analysis [42]. In practice, the interesting clinical investigations in China have verified the effects of diammonium glycyrrhizinate-vitamin C tablets on the common COVID-19 pneumonia, and its metabolite GA, which is structurally similar to corticosteroids, may act as a glucocorticoid-like drug, helping to enhance immune regulation against cytokine storms and reduce inflammation [43]. GL does not strongly down-regulate proinflammatory cytokine activity as glucocorticoids but has an immunosuppressive effect [44]. The new combination of GL, vitamin C, and curcumin has the potential to modulate the immune response after CoV infection and inhibit excessive inflammation to prevent the onset of cytokine storms [45]. Due to benign safety and the hepatoprotective effect, GL is expected to be an antidote for numerous therapeutic drugs, improving liver damage after SARS-CoV-2 infection [46].

In more recent years, there have been an increasing number of studies on the activity of GAMG. During the process of the LPS-induced RAW264.7 cell inflammatory response, GAMG showed a higher anti-inflammatory activity than GL, which may be due to the stronger inhibitory effect of GAMG on IL-6, iNOS, and COX-2. In-depth research on the anti-inflammatory mechanism of GAMG found that it could block nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPKs) signaling pathways [3][47]. High intake of GL may disturb the ion metabolic balance and may cause multiple adverse effects in animals and humans [48]. Specially, GAMG contains a glucuronic acid in its structure, which has good polarity, enabling it to pass through hydrophobic and hydrophilic cell membranes, and then play a better active role [49].

The long-term medical GL and its preparations made GL a good candidate against SARS-CoV-2 [50]. The combination of GL and boswellic acid could significantly shorten the recovery time and reduce the mortality rate of hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 infection [51]. Increased ACE2 expression during pregnancy may also increase the susceptibility of pregnant women for the virus, and GL treatment as a safer alternative to antiviral may be a good strategy [52]. GL nanoparticles (GANP) targeting severely inflamed areas significantly improved the anti-coronavirus therapeutic effect of GL through increased GANP biocompatibility, increased accumulation in the lungs and liver, enhanced the permeability and retention (EPR) action in the assimilated SARS-CoV-2-infected mouse model [53]. The National Health Commission recommended licorice and its active components for treating of COVID-19 infectious pneumonia [41]. Moreover, some derivatives of the GL have been manifested so that they have multifold antiviral activity [54].

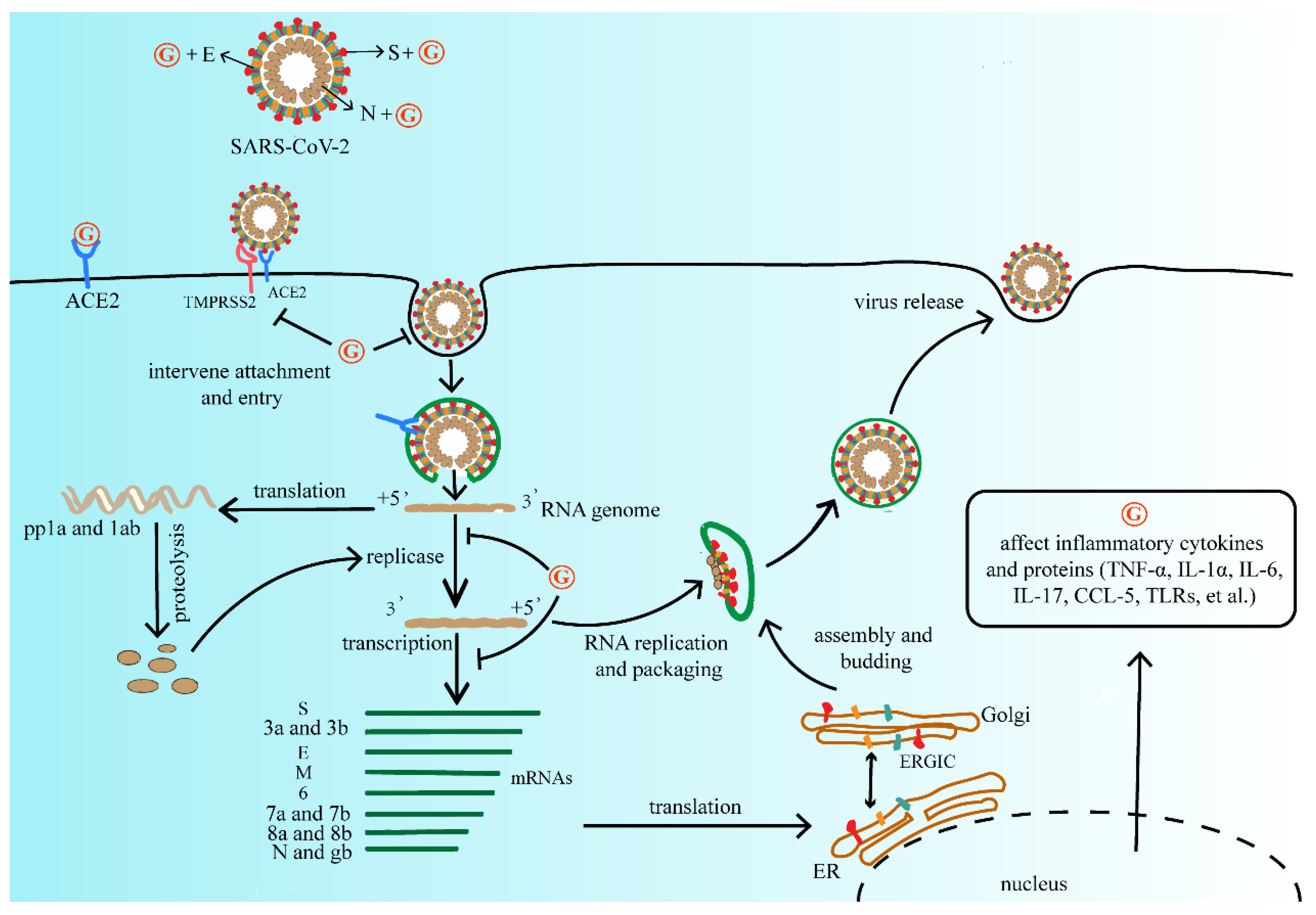

The antiviral activity of GA has also been extensively studied. Due to high safety as a natural sweetener, GA is widely used as a clinical therapeutic [55]. At present, due to the lack of effective vaccines and therapeutic drugs, GL and its metabolites have the therapeutic potential for developing products as antiviral agents. Summarizing the above studies, GL and its metabolites are widely used and generally safe compounds that the researchers consider investigating for primary prevention. It does not reduce the risk of infection, but it may mitigate the severity of the disease and reduce the burden of the medical care process. The researchers refer to the life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 and the possible inhibitory targets of antiviral drugs mentioned in Frediansyah et al., and the researchers summarize the mechanism by which GL and its metabolites may affect SARS-CoV-2 as shown in Figure 2 [56].

Figure 2. The mechanism of GL and its metabolites on the replication process of SARS-CoV-2. They may affect viral protein function, or compete with the ACE2 receptor of SARS-CoV-2, further interfere with virus adsorption, prevent virus penetration into the cell, and inhibit virus biosynthesis, at the same time decrease virus release, and finally reduce the process of viral infection. Abbreviations: G, GL and its metabolites; ACE2, angiotensin converting enzyme 2; TMPRSS2, type 2 transmembrane serine protease; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; pp1a, serine/threonine protein phosphatase 1; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1α, interleukon-1α; IL-6, interleukon-6; IL-17, interleukon-17; CCL-5, C-C motif chemokine ligand 5; TLRs, toll-like receptor.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ph16050641

References

- Chen, K.; Yang, R.; Shen, F.Q.; Zhu, H.L. Advances in Pharmacological Activities and Mechanisms of Glycyrrhizic Acid. Curr. Med. Chem. 2020, 27, 6219–6243.

- Wang, L.; Yang, R.; Yuan, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C. The antiviral and antimicrobial activities of licorice, a widely-used Chinese herb. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 310–315.

- Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Tang, W. 18α-Glycyrrhetinic acid monoglucuronide as an anti-inflammatory agent through suppression of the NF-kappaB and MAPK signaling pathway. Medchemcomm 2017, 8, 1498–1504.

- Shafik, N.M.; El-Esawy, R.O.; Mohamed, D.A.; Deghidy, E.A.; El-Deeb, O.S. Regenerative effects of glycyrrhizin and/or platelet rich plasma on type-II collagen induced arthritis: Targeting autophay machinery markers, inflammation and oxidative stress. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 675, 108095.

- Pompei, R.; Flore, O.; Marccialis, M.A.; Pani, A.; Loddo, B. Glycyrrhizic acid inhibits virus growth and inactivates virus particles. Nature 1979, 281, 689–690.

- Kim, D.H.; Hong, S.W.; Kim, B.T.; Bae, E.A.; Park, H.Y.; Han, M.J. Biotransformation of glycyrrhizin by human intestinal bacteria and its relation to biological activities. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2000, 23, 172–177.

- He, D.; Kaleem, I.; Qin, S.; Dai, D.; Liu, G.; Li, C. Biosynthesis of glycyrrhetic acid 3-O-mono-β-D-glucuronide catalyzed by β-d-glucuronidase with enhanced bond selectivity in an ionic liquid/buffer biphasic system. Process Biochem. 2010, 45, 1916–1922.

- Frediansyah, A.; Sofyantoro, F.; Alhumaid, S.; Al, M.A.; Albayat, H.; Altaweil, H.I.; Al-Afghani, H.M.; AlRamadhan, A.A.; AlGhazal, M.R.; Turkistani, S.A.; et al. Microbial Natural Products with Antiviral Activities, Including Anti-SARS-CoV-2: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4305.

- Harada, S. The broad anti-viral agent glycyrrhizin directly modulates the fluidity of plasma membrane and HIV-1 envelope. Biochem. J. 2005, 392, 191–199.

- Sun, Z.G.; Zhao, T.T.; Lu, N.; Yang, Y.A.; Zhu, H.L. Research Progress of Glycyrrhizic Acid on Antiviral Activity. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 826–832.

- Korenaga, M.; Hidaka, I.; Nishina, S.; Sakai, A.; Shinozaki, A.; Gondo, T.; Furutani, T.; Kawano, H.; Sakaida, I.; Hino, K. A glycyrrhizin-containing preparation reduces hepatic steatosis induced by hepatitis C virus protein and iron in mice. Liver Int. 2011, 31, 552–560.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Matsuura, T.; Aoyagi, H.; Matsuda, M.; Hmwe, S.S.; Date, T.; Watanabe, N.; Watashi, K.; Suzuki, R.; Ichinose, S.; et al. Antiviral activity of glycyrrhizin against hepatitis C virus in vitro. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e68992.

- Baltina, L.A. Chemical modification of glycyrrhizic acid as a route to new bioactive compounds for medicine. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 155–171.

- Lin, J.C.; Cherng, J.M.; Hung, M.S.; Baltina, L.A.; Baltina, L.; Kondratenko, R. Inhibitory effects of some derivatives of glycyrrhizic acid against Epstein-Barr virus infection: Structure-activity relationships. Antivir. Res. 2008, 79, 6–11.

- Hoever, G.; Baltina, L.; Michaelis, M.; Kondratenko, R.; Baltina, L.; Tolstikov, G.A.; Doerr, H.W.; Cinatl, J.J. Antiviral activity of glycyrrhizic acid derivatives against SARS-coronavirus. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 1256–1259.

- Baltina, L.A.; Hour, M.J.; Liu, Y.C.; Chang, Y.S.; Huang, S.H.; Lai, H.C.; Kondratenko, R.M.; Petrova, S.F.; Yunusov, M.S.; Lin, C.W. Antiviral activity of glycyrrhizic acid conjugates with amino acid esters against Zika virus. Virus Res. 2021, 294, 198290.

- Baltina, L.A.; Lai, H.C.; Liu, Y.C.; Huang, S.H.; Hour, M.J.; Baltina, L.A.; Nugumanov, T.R.; Borisevich, S.S.; Khalilov, L.M.; Petrova, S.F.; et al. Glycyrrhetinic acid derivatives as Zika virus inhibitors: Synthesis and antiviral activity in vitro. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 41, 116204.

- Murck, H. Symptomatic Protective Action of Glycyrrhizin (Licorice) in COVID-19 Infection? Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1239.

- Mahdian, S.; Ebrahim-Habibi, A.; Zarrabi, M. Drug repurposing using computational methods to identify therapeutic options for COVID-19. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2020, 19, 691–699.

- Richard, S.A. Exploring the Pivotal Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Potentials of Glycyrrhizic and Glycyrrhetinic Acids. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 6699560.

- Kuhn, J.H.; Radoshitzky, S.R.; Li, W.; Wong, S.K.; Choe, H.; Farzan, M. The Sars Coronavirus Receptor ACE2 Therapy; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 397–418.

- Wan, Y.; Shang, J.; Graham, R.; Baric, R.S.; Li, F. Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus from Wuhan: An Analysis Based on Decade-Long Structural Studies of SARS Coronavirus. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00127-20.

- Xu, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Hao, P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 457–460.

- Ke, Z.; Oton, J.; Qu, K.; Cortese, M.; Zila, V.; McKeane, L.; Nakane, T.; Zivanov, J.; Neufeldt, C.J.; Cerikan, B.; et al. Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions. Nature 2020, 588, 498–502.

- Elebeedy, D.; Elkhatib, W.F.; Kandeil, A.; Ghanem, A.; Kutkat, O.; Alnajjar, R.; Saleh, M.A.; Abd, E.M.A.; Badawy, I.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities of tanshinone IIA, carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acid, baicalein, and glycyrrhetinic acid between computational and in vitro insights. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 29267–29286.

- Izcovich, A.; Ragusa, M.A.; Tortosa, F.; Lavena, M.M.; Agnoletti, C.; Bengolea, A.; Ceirano, A.; Espinosa, F.; Saavedra, E.; Sanguine, V.; et al. Prognostic factors for severity and mortality in patients infected with COVID-19: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241955.

- Negru, P.A.; Radu, A.F.; Vesa, C.M.; Behl, T.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Nechifor, A.C.; Endres, L.; Stoicescu, M.; Pasca, B.; Tit, D.M.; et al. Therapeutic dilemmas in addressing SARS-CoV-2 infection: Favipiravir versus Remdesivir. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112700.

- Vardhan, S.; Sahoo, S.K. In silico ADMET and molecular docking study on searching potential inhibitors from limonoids and triterpenoids for COVID-19. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 124, 103936.

- Br, B.; Damle, H.; Ganju, S.; Damle, L. In silico screening of known small molecules to bind ACE2 specific RBD on Spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 for repurposing against COVID-19. F1000Research 2020, 9, 663.

- Yu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yao, G.; Zhang, P.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, G.; Chen, H.; Chen, L.; et al. Glycyrrhizic acid exerts inhibitory activity against the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Phytomedicine 2021, 85, 153364.

- Sinha, S.K.; Prasad, S.K.; Islam, M.A.; Gurav, S.S.; Patil, R.B.; AlFaris, N.A.; Aldayel, T.S.; AlKehayez, N.M.; Wabaidur, S.M.; Shakya, A. Identification of bioactive compounds from Glycyrrhiza glabra as possible inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and non-structural protein-15: A pharmacoinformatics study. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 39, 4686–4700.

- Ahmad, S.; Waheed, Y.; Abro, A.; Abbasi, S.W.; Ismail, S. Molecular screening of glycyrrhizin-based inhibitors against ACE2 host receptor of SARS-CoV-2. J. Mol. Model. 2021, 27, 206.

- Li, J.; Xu, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, G.; Li, E.; He, S. Glycyrrhizic Acid Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Blocking Spike Protein-Mediated Cell Attachment. Molecules 2021, 26, 6090.

- Diomede, L.; Beeg, M.; Gamba, A.; Fumagalli, O.; Gobbi, M.; Salmona, M. Can Antiviral Activity of Licorice Help Fight COVID-19 Infection? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 855.

- Ni, Q.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, B.; Han, J.; Chen, S. Analysis of the network pharmacology and the structure-activity relationship of glycyrrhizic acid and glycyrrhetinic acid. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1001018.

- Fatima, S.W.; Alam, S.; Khare, S.K. Molecular and structural insights of beta-boswellic acid and glycyrrhizic acid as potent SARS-CoV-2 Envelope protein inhibitors. Phytomed. Plus 2022, 2, 100241.

- Ray, M.; Sarkar, S.; Rath, S.N. Druggability for COVID-19: In silico discovery of potential drug compounds against nucleocapsid (N) protein of SARS-CoV-2. Genom. Inform. 2020, 18, e43.

- Khater, S.; Kumar, P.; Dasgupta, N.; Das, G.; Ray, S.; Prakash, A. Combining SARS-CoV-2 Proofreading Exonuclease and RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Inhibitors as a Strategy to Combat COVID-19: A High-Throughput in silico Screening. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 647693.

- Patil, R.; Chikhale, R.; Khanal, P.; Gurav, N.; Ayyanar, M.; Sinha, S.; Prasad, S.; Dey, Y.N.; Wanjari, M.; Gurav, S.S. Computational and network pharmacology analysis of bioflavonoids as possible natural antiviral compounds in COVID-19. Inform. Med. Unlocked 2021, 22, 100504.

- Yi, Y.; Li, J.; Lai, X.; Zhang, M.; Kuang, Y.; Bao, Y.O.; Yu, R.; Hong, W.; Muturi, E.; Xue, H.; et al. Natural triterpenoids from licorice potently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 36, 201–210.

- Luo, P.; Liu, D.; Li, J. Pharmacological perspective: Glycyrrhizin may be an efficacious therapeutic agent for COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105995.

- Zheng, W.; Huang, X.; Lai, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhan, S. Glycyrrhizic Acid for COVID-19: Findings of Targeting Pivotal Inflammatory Pathways Triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 631206.

- Ding, H.; Deng, W.; Ding, L.; Ye, X.; Yin, S.; Huang, W. Glycyrrhetinic acid and its derivatives as potential alternative medicine to relieve symptoms in nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2200–2204.

- Xu, X.; Gong, L.; Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mei, X.; Xu, H.; Tang, L.; Liu, R.; Zeng, Z.; et al. Glycyrrhizin Attenuates Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Infection: New Insights Into Its Protective Mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2321.

- Chen, L.; Hu, C.; Hood, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Kan, J.; Du, J. A Novel Combination of Vitamin C, Curcumin and Glycyrrhizic Acid Potentially Regulates Immune and Inflammatory Response Associated with Coronavirus Infections: A Perspective from System Biology Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1193.

- Tian, X.; Gan, W.; Nie, Y.; Ying, R.; Tan, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, C. Clinical efficacy and security of glycyrrhizic acid preparation in the treatment of anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug-induced liver injury: A protocol of systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051484.

- Zhang, X.L.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Xie, Y.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Zhang, J. 18beta-Glycyrrhetinic acid monoglucuronide (GAMG) alleviates single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT)-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis in mice through PI3K/AKT/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 242, 113858.

- Guo, L.; Katiyo, W.; Lu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, M.; Yan, J.; Ma, X.; Yang, R.; Zou, L.; Zhao, W. Glycyrrhetic Acid 3-O-Mono-beta-D-glucuronide (GAMG): An Innovative High-Potency Sweetener with Improved Biological Activities. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 905–919.

- Lu, D.Q.; Li, H.; Dai, Y.; Ouyang, P.K. Biocatalytic properties of a novel crude glycyrrhizin hydrolase from the liver of the domestic duck. J. Mol. Catal B Enzym. 2006, 43, 148–152.

- Bailly, C.; Vergoten, G. Glycyrrhizin: An alternative drug for the treatment of COVID-19 infection and the associated respiratory syndrome? Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 214, 107618.

- Gomaa, A.A.; Mohamed, H.S.; Abd-Ellatief, R.B.; Gomaa, M.A.; Hammam, D.S. Advancing combination treatment with glycyrrhizin and boswellic acids for hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 infection: A randomized clinical trial. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 477–486.

- Zhao, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xi, H.; Liu, C.; Qu, F.; Feng, X. Analysis of the susceptibility to COVID-19 in pregnancy and recommendations on potential drug screening. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1209–1220.

- Zhao, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, G.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Zhu, T.; Tan, Q.; Tang, L.; et al. Glycyrrhizic Acid Nanoparticles as Antiviral and Anti-inflammatory Agents for COVID-19 Treatment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 20995–21006.

- Xiao, S.; Tian, Z.; Wang, Y.; Si, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, D. Recent progress in the antiviral activity and mechanism study of pentacyclic triterpenoids and their derivatives. Med. Res. Rev. 2018, 38, 951–976.

- Ploeger, B.; Mensinga, T.; Sips, A.; Seinen, W.; Meulenbelt, J.; DeJongh, J. The pharmacokinetics of glycyrrhizic acid evaluated by physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling. Drug Metab. Rev. 2001, 33, 125–147.

- Frediansyah, A.; Tiwari, R.; Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Harapan, H. Antivirals for COVID-19: A critical review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 9, 90–98.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!