Since the earliest descriptions of the simple visual hallucinations in migraine patients and in subjects suffering from occipital lobe epilepsy, several important issues have arisen in recognizing epileptic seizures of the occipital lobe, which often present with symptoms mimicking migraine. A detailed quantitative and qualitative clinical scrutiny of timing and characteristics of visual impairment can contribute to avoiding mistakes. Differential diagnosis, in children, might be challenging because of the partial clinical, therapeutic, and pathophysiological overlaps between the two diseases that often coexist. Ictal elementary visual hallucinations are defined by color, shape, size, location, movement, speed of appearance and duration, frequency, and associated symptoms and their progression. The evaluation of the distinctive clinical features of visual aura in migraine and visual hallucinations in occipital epilepsy could contribute to understanding the pathogenetic mechanisms of these two conditions.

1. Visual Symptoms in Migraine

Among children and adolescents suffering from migraine (5% in pre-pubertal children, with percentages increasing throughout adolescence), approximately one-third have migraine with aura (MA) [

9,

10,

11]. Typical aura without headache is rarely described and actual prevalence is still debated; some authors report from 1.8 to 2% [

12,

13], and others found that 44% of patients are affected by migraine with aura [

14]. The most common type of aura is visual aura (87.1%), followed by sensory (38.5%) and speech and language auras (15.6%). A confusional state is present in 10.9% of patients [

10], whereas olfactory hallucinations accompany approximately 3.9% of pediatric migraine aura cases [

15]. Panayiotopoulos described well the clinical features of visual hallucination in migraine. It is now well-known that they differ from epileptic hallucinations in terms of color, shape, size, location and movement in the visual field, frequency, and associated symptoms. A peculiar and distinctive feature of the visual aura is the gradual onset and progression, in contrast to the sudden onset typical of epilepsy, cerebral ischemia, or hemorrhage [

7]. Based on their characteristics, visual symptoms can be distinguished as “negative” (vision loss) or “positive” (with flashing, shimmering, or scintillating patterns) [

16]; and simple (dots or other simple shapes) or complex (more prominent and more elaborate vision disturbances, such as the perception of fortification spectra and other illusions). Usually, elementary visual disturbances in migraine aura develop slowly within 4 min and usually last 15–20 min, and up to 60 min (IHS 2018); they have mainly uncolored or black and white patterns, although frequency of up to 40% of colorful aura is reported [

17,

18], and are represented by linear or zig-zag achromatic shapes [

18,

19], first appearing in the center of the visual field and then moving peripherally. In most cases, simple positive visual hallucinations are followed by a scotoma. Scintillating scotoma and blurry vision are the most frequent visual symptoms in children, followed by tunnel vision and zig-zag lines [

20]. Moreover, most frequently than adults, children complain of color dysgnosia caused by unusual color brightness that prevents patients from recognizing color shades [

20,

21]; less frequently, adult patients complain of dimmed colors or achromatopsia, usually often associated with both prosopagnosia and loss of spatial orientation [

22]. Theoretically, color perception changes could result from photophobia or a direct migraine effect on color processing, as Noseda et al. suggested, originating in the retina and thalamus rather than in cortical visual processing areas [

23]. Visual aura rarely occurs with accompanying neurologic findings that are typical manifestations of epileptic seizures (i.e., tonic deviation of the eyes and alterations in consciousness). In our digression, it is essential to make a point: headaches are not always associated with auras and, in particular, auras do not always precede a headache. In this regard, we recall an uncommon diagnosis of typical aura without headache (TAH), which is neither accompanied nor followed by headache [

24].

2. Visual Symptoms in Epilepsy

In most pediatric cases, visual disturbances are the typical manifestation of idiopathic childhood epilepsy with occipital paroxysms (Gastaut-type). This idiopathic epilepsy represents approximately 2 to 7% of benign childhood focal seizures [

6], with an estimated prevalence of 0.3% in children and peak incidence between 8 and 9 years of age [

6]. The hallmark of this childhood epilepsy syndrome is predominantly diurnal visual seizures [

6] characterized by brief elementary visual hallucinations, deviation of the eyes, and blindness. Sometimes, autonomic symptoms follow the visual symptoms and evolve into a dyscognitive seizure. Usually, but not always, typical occipital paroxysms are detectable using EEG [

25].

Elementary visual hallucinations are stereotyped, multi-colored, and circular. Frequently, they appear on the edge of a temporal hemifield, multiply in number and size, often move horizontally towards the other side, and may flash or be static. Usually, they develop within seconds and generally last up to 1 to 3 min. In a recent comparative analysis of visual symptoms, the median duration was reported as 56 s and 20 min in epileptic and adult patients affected by migraine, respectively [

26]. Stereotypic lateralization of the visual phenomena was reported to be significantly more common in epilepsy than in migraine [

26]. Visual hallucinations can occur in different diseases and might be caused by structural lesions in the posterior temporal–occipital regions, including cortical dysplasia, encephalomalacia, low-grade glial tumors, vascular malformations, and occipital calcifications [

27].

3. Visual Symptoms in Both Conditions: Epilepsy and Migraine

There is substantial variability in the characteristics of visual aura, with some commonalities across individuals. Recently, Viana et al. undertook a comprehensive review of all currently available data from clinical studies dealing with visual hallucinations in migraineur adults [

28] and showed how different, and often complex, visual disturbances could be. Despite the smaller amount of evidence compared to adult patients, unusual visual aura has also been reported in children and adolescents. Polychromatic figures and formed shapes (e.g., dots, circles, triangles, squares, stars) [

29] can mimic occipital seizures but duration, localization, and movement pattern, as previously mentioned, may provide guidance for the correct diagnosis (

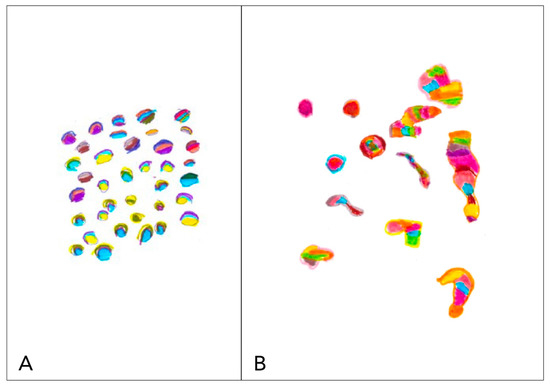

Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graphical representation of phosphenes. We report two explanatory drawings, drawn by two children who arrived at the Department of Neuropsychiatry of Di Cristina Hospital in Palermo. (A) Graphic representation of phosphenes in a child with occipital epilepsy with seizure without loss of consciousness. (B) Graphic representation of phosphenes in a child with migraine with aura. The high similarity between the two symptoms complicates the differential diagnosis. (Courtesy of Dr. V. Raieli).

Unfortunately, visual disturbances such as visual loss (scotoma, amaurosis, and blindness), palinopsia, blurring vision, and macro or micropsia (as in the Alice in Wonderland syndrome) are more challenging and may mislead clinicians. In those cases, a detailed clinical history may reveal the event’s true nature and further direct investigations [

30].

3.1. Visual Loss

Ictal amaurosis, blindness, or severe blurring of vision, limited to one hemifield, quadrant, or involving the entire visual field are common ictal phenomenon in idiopathic childhood occipital epilepsy (Gastaut-type), occurring in-two thirds of such patients and usually following the visual hallucinations, and last up to 5 min [

31]. However, they may occasionally constitute the first symptom or the only ictal manifestation with abrupt onset [

32,

33,

34]. In 70% of patients [

4], it is associated with horizontal deviation of the eyes and progresses to varying associated focal convulsions. In the absence of any other seizure phenomenon, it may not be possible to differentiate migraine-induced transient cortical blindness from that induced by a seizure disorder. Migraine-induced transient cortical blindness can result from the scotoma resulting from the visual aura or can underlie a basilar or retinal migraine (

Figure 2).

Figure 2. Graphical representation of blindness. We report explanatory drawing of blindness, drawn by a child with migraine who visited the Department of Neuropsychiatry of Di Cristina Hospital in Palermo. Translation of the written portion: “I don’t see anything”. (Courtesy of Dr. V. Raieli).

Retinal migraine is sporadic among pediatric migraine patients, accounting for <2%; in this disorder, monocular scotoma or vision loss is reported, rather than hemifield deficits typical in the visual aura.

3.2. Palinopsia and Polioplia

Palinopsia is derived from the Greek words palin (again) and opsis (vision) and describes the perseveration of visual images. Palinopsia is a cardinal symptom of ictal clinical manifestations of occipital lobe seizures [

34]. Belcastro et al. 2011 [

35] described palinopsia events that lasted for seconds in 10% of 200 adults affected by migraine with and without aura. Polyopia is an uncommon visual phenomenon and an infrequent symptom of central nervous system disease, mainly occipital or temporal lesions [

36], often associated with palinopsia, defined as the perception of many copies of objects or faces [

37]. An interesting case report with a child affected by polioplia associated with the hemianopsia during migraine attack has been described in children affected by migraine [

38,

39]

3.3. Visual Snow

Visual snow is described as the electronic “snow” on a television set when the primary video signal is either reduced or absent, as well as pixelated fuzz and bubbles. It can be due to different etiologies and it has variable duration. When this symptom is associated with palinopsia, enhanced entoptic imagery, “nyctalopia”, and photophobia/photosensitivity, visual snow syndrome (VSS) can be diagnosed. In the anecdotal cases of migrainous patients reported in the literature [

40], visual snow is usually short and without associated symptoms. In contrast, VSS was reported by Polster et al. [

41] in two patients with suspected occipital epilepsy.

3.4. Other Complex Positive Symptoms

In migraineur children, visual hallucinations including landscapes, animals, human bodies, or faces, or the perception of mysterious objects that may aggregate to form complex scenes, are limited to anecdotical reports [

42,

43]. As epileptic symptoms, Panayiotopoulos described only three patients who reported “large objects, probably people, which I cannot identify”. Clear perception of people is reported in adults affected by different disease (hemorrhage, stroke, malformations, neoplasia) and are usually associated with medial temporolimbic seizure [

44], and less commonly with lateral temporal seizure and rarely with occipital seizure [

45]. In contrast, perceptual distortions of the patient’s body or objects in the environment, as described in Alice in Wonderland syndrome (AWS), are frequently reported in children [

12,

46]. AWS can present as micropsia (objects appear too small), macropsia (objects appear too large), metamorphopsia (objects appear too fat, thin, short, tall, etc.), teleopsia (objects appear further away than they are), and pelopsia (objects appear closer than they are). The symptom duration is widely variable, differs in each person, and resolves without sequelae. The cause of these symptoms is debated and remains unknown in almost 20% of cases [

46]. In 2016, Blom et al. [

46] showed that out of 166 published cases of AIWS, migraine was the most common cause (27.1%), followed by infections (22.9%), principally EBV (15.7%), brain lesions (7.8%), medication (6%) and drugs (6%), psychiatric disorders (3.6%), temporal or focal epilepsy (3%), disease of the peripheral nervous system (1.2%), and others (3%). In nearly 50% of patients [

47], a family history of migraine or Alice in Wonderland syndrome can be detected. When occurring in children without other conditions, it usually predicts a higher chance of developing migraines in the future [

16]. When AWS is associated with migraine, the symptoms can occur before, during, or after a migraine headache; micropsia and teleopsia have been more frequently reported [

48].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/brainsci13040643