Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Cigarette smoking (CS) or ambient particulate matter (PM) exposure is a risk factor for metabolic disorders, such as insulin resistance (IR), increased plasma triglycerides, hyperglycemia, and diabetes mellitus (DM); it can also cause gut microbiota dysbiosis. In smokers with metabolic disorders, CS cessation decreases the risks of serious pulmonary events, inflammation, and metabolic disorder.

- cigarette smoking

- lung–gut axis

- inflammation

- particulate matter

1. CS Exposure Induces Lung Inflammation and Diabetes Mellitus Progression

CS is a complex mixture including various compounds with suspended PM and gases [13]. Indoor PM2.5 (PM with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 2.5 μm) was the most reliable indicator in CS [14]. CS exposure can cause chronic inflammatory lung disease and lung infection and predispose individuals to acute lung injury [15]. Airway epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages exposed to CS alter inflammatory signaling leading to the recruitment of eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and mast cells to the lung—depending on the activation of different signaling pathways, such as Nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), c-Jun N-terminal kinase, p38, and STAT3 [16]. In addition, CS is also considered a critical risk factor for metabolic disorder and metabolic syndrome (MetS). Metabolic disorders occur when aberrant chemical reactions in the body alter normal metabolic processes. However, MetS encompasses a spectrum of metabolic abnormalities, including hypertension, obesity, IR, and atherogenic dyslipidemia, and is strongly associated with an increased risk of diabetic cardiovascular disease [17]. Notably, CS may induce MetS, which is characterized by reduced insulin sensitivity, increased IR and plasma triglyceride levels, and mediated hyperglycemia [18]. Several clinical studies have indicated a close link between MetS and lung disease [19]. MetS comprises a cluster of risk factors specific for lung inflammation diseases, such as obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus (DM), and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [20,21]. CS exposure is strongly associated with an increased risk of progression of various diseases, including DM, cardiovascular disease, and COPD. However, prolonged CS cessation can reduce these risks.

A meta-analysis of prospective observational studies study revealed that there is a linear dose-response relationship between CS and the risk of T2DM; however, the risk steadily declined after smoking cessation [22]. There was a dose-response relationship between HbA1c (blood sugar/glucose test) levels and CS exposure of current smokers, and there was an inverse association between the number of years since smoking cessation with HbA1c levels has been detected among ex-smokers [23]. The adverse effects of CS and hyperglycemia aggravate vascular damage in patients with DM [24]. Eliasson et al. reported a dose-dependent correlation between the per-day CS quantity and IR degree [25]. Acute CS can impair glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity as well as increase serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels, blood pressure, and heart rate [26], whereas CS cessation can improve insulin sensitivity [27]. Moreover, CS is an independent predictor of T2DM, and CS cessation can reduce the risk of MetS [28]. Serious pulmonary events (SPEs) reduced exercise capacity and lung dysfunction and might be a clinical indicator of pre-DM or undiagnosed DM [24]. CS cessation can reduce SPE risk, morbidity, and mortality in people with DM. For instance, in DM mice, CS exposure was reported to accelerate edema and inflammatory progression, whereas CS cessation alleviated CS-mediated metabolic disorder and IR [27]. Also, DM is strongly correlated with pulmonary complications, including COPD, fibrosis, pneumonia, and lung cancer [29]. In patients with COPD combined with DM, metformin—the first-line drug for T2DM—can increase inspiratory muscle strength, leading to dyspnea and COPD alleviation as well as health status and lung function improvements [30,31]. Although the strong association of DM with inflammation-related chronic lung disease, particularly asthma and COPD, has been demonstrated epidemiologically and clinically, the underlying mechanism and pathophysiology remain unclear [32]. Numerous mechanisms have been reported; most of them have implicated the association of lung disease with DM-related inflammatory properties or pulmonary microvascular and macrovascular complications [33]. DM, combined with progression to pulmonary disease, is characterized as a chronic and progressive disease with high mortality and extremely few therapeutic options, possibly including metformin and thiazolidinediones [32,34,35]. Collectively, the complex consequences mediated by CS exposure lead not only to lung inflammation but also to the progression of MetS. In the next section, we continue to review emerging studies on CS-mediated systemic inflammation and metabolic diseases associated with gut microbiota dysbiosis.

2. Association of CS Exposure with Gut-Derived Microbiota and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

CS-related microbiota dysbiosis may be associated with numerous inflammatory lung diseases (including COPD, asthma, cystic fibrosis, and allergy) and metabolic disorders (such as IR, glucose metabolic disorder, hypertriglyceridemia, and DM) [14,36,37]. However, the relationship of CS with gut-derived microbiota biofunction and their dietary nutrient–derived metabolites warrants elucidation. Even with an improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying the progression of inflammation-associated lung disease, CS-associated metabolic disorder remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally. Several epidemiological studies have indicated a high correlation between intestinal microbiota and the lungs—termed the lung–gut axis [1]. Gut microbiota dysbiosis is associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and it influences the gut epithelial barrier function and leads to increased immune response and chronic inflammatory disease and metabolic disorder pathogenesis. Moreover, IBD is strongly linked with COPD, DM, and gut microbiota dysbiosis [38,39]. Alterations in gut microbiota due to an imbalanced diet may lead to enhanced local and systemic immune responses. Gut microbiota dysbiosis has been linked to not only the loss of gastrointestinal tract function but also that of airway function, such as that in asthma and COPD [1]. Moreover, CS-elicited dysbiosis has a protumorigenic role in colorectal cancer. CS-associated gut microbiota dysbiosis alters gut metabolites and diminishes gut barrier function, activating oncogenic MAPK/ERK signaling in the colonic epithelium [40]. Taken together, these results indicate that CS mediates not only the dysbiosis of gut microbiota and the dysregulation of their metabolites but also systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation in the lung–gut axis. In addition, ambient PM-mediated systemic inflammation and metabolic disease may also be associated with dysregulation of the lung–gut axis, as reviewed later.

3. PM Exposure Triggers Lung Inflammation, Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis, and DM Progression

Chronic exposure to particulate pollution such as PM2.5 can also lead to decreased lung function, emphysematous lesions, and airway inflammation [41,42], and it accelerates CS-induced alterations in COPD progression [36]. Ambient air pollution is associated with decreased lung function and increased COPD prevalence in a large cohort study [12]. Furthermore, urban PM exposure markedly increased airway inflammatory responses through the activation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-MAPK-NF-κB signaling [43]. Thus, PM exposure contributes to respiratory disease by triggering lung inflammation and increasing oxidative stress.

Notably, recent studies have linked PM exposure to intestinal disorders such as appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and IBD [44,45]. In addition, the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and intestinal permeability is increased in the small intestine of mice exposed to PM10 [46]. PM-mediated dysbiosis of the microbiota is also correlated with PM-mediated gut and systemic effects. Long-term exposure to PM, such as O3, NO2, SO2, PM10, and PM2.5, as well as traffic-related air pollution, has been shown to alter microbiota diversity [47]. Moreover, both PM2.5 and PM1 exposure are positively associated with the risks of fasting glucose impairment or T2DM and negatively associated with alpha diversity indices of the gut bacteria [48]. Through systematic database analysis, air pollution exposure is a leading cause of insulin resistance and T2DM. Besides, the association between air pollution and diabetes is stronger for particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, and traffic-associated pollutants [10]. In a meta-analysis study, exposure to PM2.5 but not PM10 or NO2 is correlated with increased disease incidence in T2DM patients [49]. Particularly, chronic ambient PM2.5 exposure is associated with increased T2DM risk in several Asian populations exposed to high levels of air pollution [50]. Through global untargeted metabolomic analysis, several significant blood metabolites and metabolic pathways were identified associated with chronic exposure to PM2.5, NO2, and temperature; these included glycerophospholipid, glutathione, and sphingolipid propanoate as well as purine metabolism and unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis [51]. In mice, PM2.5 exposure was reported to lead to increased oxidative stress, glucose intolerance, IR, and gut dysbiosis and impaired hepatic glycogenesis [52]. In rats with T2DM, short-term PM2.5 exposure significantly increased IR as well as the lung levels of inflammatory factors, such as interleukin (IL) 6, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α [39]. High levels and prolonged periods exposure to concentrated ambient PM2.5-mediated gut dysbiosis was associated with the metabolic disorder and intestinal inflammation [53]. Taken together, these findings indicate that air pollution particles not only mediate the pathogenesis of lung inflammation disease but also increase gut microbiota dyshomeostasis and metabolic disorders, such as IR and DM.

4. CS and PM Exposure Mediates Systemic Inflammation and Metabolic Disorders Associated with Lung–Gut Axis Disruption

Emerging studies on the effects of particulate pollution, such as CS and PM exposure, on the systemic inflammation and metabolic disorder associated with the lung–gut axis. Exposure to CS and PM2.5 is a critical risk factor for intestinal dysfunction, which comprises intestinal microbiota dysbiosis, enhanced permeability of the mucosal barrier, and induce mucosal immune responses [54,55]. The toxic constituents of cigarette smoke include carboxylic acids, phenols, humectants, nicotine, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, acetaldehyde, 1,3-butadiene, N-nitrosamines, benzene, aromatic amines, acrolein, and polyaromatics, all of which are inhaled into the lungs [56], followed by their absorption into the blood system and then into the gastrointestinal tract; this causes dysbiosis of gut microbiota through the inhibition of their bioactivity and thus alterations in the intestinal microenvironment [57]. Moreover, these toxic compounds induce lung oxidative stress, gut microbiota dysbiosis, intestinal dysfunction, and extreme systemic inflammation. CS-exposed mice were noted to have impaired gut barrier function and elevated serum LPS levels compared with those not exposed to CS [40]. After 24 weeks of PM (biomass fuel or motor vehicle exhaust) exposure, rats were noted to display lung inflammation, which progressed to COPD. Their gut microbiota demonstrated decreased microbial richness and diversity and decreased SCFA levels, but increased serum LPS levels were found [58]. In young patients with hypertension, the metal constituents of PM2.5 were noted to elevate blood pressure and increase the plasma levels of the microbial metabolite trimethylamine TMAO [59]. PM mediates gut barrier function loss, thereby increasing gut permeability and consequently resulting in the entry of bacteria, bacterial endotoxin, bacterial metabolite, or all leak into circulation [60]. As well, dysregulated gut epithelial barrier, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and accelerated gut microbial product translocation promote lung inflammation [61]. In fact, the harmful components carried by ambient PM may vary according to the level and duration of environmental pollution exposure, leading to different degrees of lung deposition, inflammation and injury. However, either CS or PM may worsen IBD, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and microbiota-derived metabolite alterations, thus mediating systemic inflammation and metabolic disorder development by increasing LPS and TMAO levels and reducing SCFA levels. Below, we highlight recent studies that provide insight into the implication of particulate pollution exposure in aggravating systemic inflammation and metabolic disease through complex interplaying processes, including lung inflammation and injury, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and the production of corresponding metabolites.

5. Mechanisms Underlying CS and PM Exposure Aggravate Inflammation and Development of Metabolic Disorder through the Lung–Gut Axis

CS or PM inhalation studies have mostly focused on the effects of air pollution on inducing lung inflammatory response, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction; however, the effects of PM on gut microbiota and its role in metabolic disease pathogenesis are largely unknown. CS-mediated chronic airway inflammation is a major COPD pathogenesis driver [62,63]. CS also mediates gut microbiota dysbiosis [40]. Gut microbiota dysbiosis has a potential role in CS-related pathogenesis, such as that in metabolic disorders and DM. When in homeostasis, the gut microbiome has a high diversity of microbiota, such as bacteria from the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and Proteobacteria [64]. Smokers’ gut microbiome differs from that of nonsmokers. The gut microbiota of the majority of current smokers includes a lower number of bacteria from Firmicutes but a higher number of bacteria from Bacteroidetes [65]. After CS cessation, these individuals demonstrate an increase in Actinobacteria and Firmicutes populations but a decline in Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes populations [66,67]. Specifically, observational and interventional studies have revealed that current smokers have increased Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes populations but decreased populations of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes as well as Bifidobacterium spp. and Lactococcus spp.—along with low gut microbiome diversity [66,68]. Current smokers have also been reported to have increased numbers of Proteobacteria as well as of Bacteroides spp. and Prevotella spp. in their feces; however, this abundance has been observed to decrease after CS cessation, with an increase in the numbers of Firmicutes (Clostridium coccoides, Clostridium leptum subgroup, and Eubacterium rectale) and Actinobacteria (Bifidobacterium) [69,70]. CS or bidi smoking is correlated with Erysipelotrichi and Catenibacterium abundance in a dose-response manner, where CS exposure leads to the enrichment of the relative abundance of Erysipelotrichi–Catenibacterium [71]. Adult mice exposed to CS have been reported to exhibit significantly reduced Firmicutes abundance but significantly increased Bacteroidetes abundance. CS-exposed mice also demonstrated significant alterations; Eggerthella lenta population enrichment and Lactobacillus spp. population decline [40]. Firmicutes (gram-positive) represent one of the most abundant and exclusive phyla in the intestines [72]. CS patients with active Crohn’s disease may have significantly higher Bacteroides–Prevotella levels than do nonsmokers [69]. Moreover, increases in the population of bacteria causing proinflammatory pathway activation might cause CS-mediated deleterious effects [73]. As mentioned, CS may reduce Firmicutes and increase Bacteroidetes populations; nevertheless, CS cessation can enable the return of the populations to their original levels. CS reduces the number of the SCFA-producing bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis, causing a disparity in a cigarette smoker’s SCFA profile [74]. CS reduces the levels of the dietary fiber–friendly SCFA-generating Firmicutes bacteria but not the levels of Bacteroidetes bacteria. A study suggested a novel treatment for emphysema: high-fiber diet administration followed by feces microbiota transplantation [75].

Notably, disruption of the microbiota resulted in lower SCFA levels after exposure to air pollution; this effect is linked with metabolic disorders. When rats were exposed to CS for 4 weeks, the cecal levels of SCFAs, such as acetic acid, propionic acid, butyric acid, and valeric acid, decreased significantly. Moreover, Bifidobacterium spp. significantly decreased, whereas pH in caecal contents significantly increased [76]. Intragastric administration of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) in mice caused inflammation in the intestinal mucosa, which induced alterations in Paneth cell granules and reduced their bactericidal capacity [57]. CSC exposure caused an imbalance in the gut bacterial population, promoting bacterial infection and causing ileal damage in mice. Moreover, CSC significantly increased the abundance of bacteria from Erysipelotrichaceae but considerably reduced that of Rikenellaceae. A significant decrease was also noted in the abundance of Eisenbergiella spp. (from the family Lachnospiraceae), known for its butyrate generation capacity [77]. CS cessation-related alterations in the gut microbial ecosystem have, however, been linked to weight gain in mice [78]. The concentrations of SCFAs (i.e., acetate, butyrate, and propionate) were the lowest in mice with CS-induced emphysema; on the contrary, local SCFA levels were significantly higher in the emphysema with high-fiber (pectin and cellulose) diet group than in the untreated emphysema group [75]. In diesel exhaust particles-treated mice, dysbiosis of the gut microbiota population was associated with a dose-dependent decrease of SCFAs (butyrate and propionate) in cecal content [79]. Collectively, accumulating findings suggest that CS- or PM-mediated lung injury is closely associated with altered gut microbiota and low SCFA production.

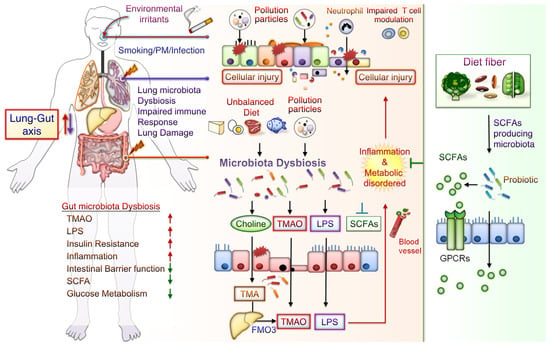

The potential mechanisms underlying the effects of CS-mediated metabolic disorders include inducing gut microbiota dysbiosis, increased oxidative stress, disrupted intestinal tight junctions, and increased systemic inflammation. Notably, some CS-mediated gut microbiota changes are similar to those demonstrated during the progression of conditions such as IBD, IR, glucose metabolic disorders, and DM. Besides, metabolomic analysis has revealed that CS exposure increases the levels of bile acid metabolites, particularly taurodeoxycholic acid (TDCA), in the colons of mice. These mice also had an upregulated TDCA–mitogen-activated protein kinase-extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1/2 axis and damaged gut barrier function [40]. Intratracheally instillated diesel PM2.5 in mice led to significant increases in the numbers of bacteria from Firmicute, specifically those from the family Enterobacteriaceae, and decreases in those from Bacteroidetes, specifically bacteria from the family Porphyromonadaceae [80]. Long-term exposure to PM2.5 for 12 months in mice resulted in IR and impaired glucose tolerance, which was linked to the alternations of gut bacterial communities richness and gut microbiota composition [55]. PM2.5, therefore, mediates changes in the microbiome composition; this might lead to metabolic disorder pathogeneses. Further exploration of the mechanisms underlying CS- and PM-associated microbiota dysbiosis is warranted. These findings may aid in elucidating whether air pollution-related gut microbiota alterations contribute to CS- and PM-related inflammation and metabolic disorders. The potential effects of CS or PM exposure on the lung–gut axis are schematically represented in Figure 1. CS or PM inhalation leads to gut microbiota dysbiosis and consequently increases the levels of TMAO and LPS, leading to system inflammation and exacerbated metabolic disorders. Notably, SCFA/GPCR signaling may retain gut barrier function and suppress inflammation. In addition, dietary fiber fermentation by certain specific gut microbiota can increase SCFA production. Thus, reducing microbiota dysbiosis and its attendant products attenuates lung inflammation and cellular injury by the lung–gut axis, which may prevent systemic inflammation and metabolic dysregulation.

Figure 1. Potential Effects of CS or PM exposure on the lung–gut axis, leading to aggravating systemic inflammation and metabolic disorders. Cigarette smoking (CS) and ambient particulate matter (PM) are critical factors mediating gut microbiota dysbiosis and changes in microbiota-derived metabolites. Microbiota endotoxins and metabolites, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), metabolite trimethylamine (TMA), N-oxide (TMAO), and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), participate in the regulation of system inflammation, which influences lung function. CS or PM inhalation leads to gut microbiota dysbiosis. Gut dysbiosis may, in turn, increase the levels of TMA—which is then converted to TMAO by the liver enzyme flavin-containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3). Dietary fiber fermentation by distinct SCFA-associated gut microbiota leads to SCFA generation. Activation of SCFA/G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling is crucial for maintaining gut barrier function and inhibiting inflammation. Thus, targeting the lung–gut axis may prevent systemic inflammation and metabolic disease.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells12060901

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!