Integration and harmonization of the most recent seismological, geological, tectonic, geophysical and geodetic datasets, with the aim of capturing the potential of ground deformation towards a more reliable evaluation of seismic risk at a national level.

- seismotectonics

- crustal deformation

- GIS mapping

1. Introduction

Inasmuch as earthquake hazards crown the list of possible natural threats in Greece, seismotectonic studies and maps are necessary for the prevention and mitigation of pertinent disasters. It has been over 30 years since the first Seismotectonic Map of Greece was published by the Institute of Geological and Mining Research in 1989 [1]. Therefore, it is imperative to update the map, given that since an extensive body of geological, tectonic, seismological, geophysical, geodetic and volcanological information has been accumulated and dozens of significant earthquakes have occurred. This wealth of information has improved our understanding of the geodynamics of Greece, and could be used to improve our capacity to forecast earthquake hazards and plan the mitigation of disasters in the context of rapidly expanding industrial and economic activities.

2. The Atlas interactive database

The data incorporated in the new Seismotectonic Atlas of Greece are composed of sets of active faults, historical and instrumental era seismicity, focal mechanisms, stress and strain-rate field distributions, active volcanoes, historical and instrumental era tsunamis, gravity and magnetic anomalies. Each of these datasets has been constructed as a GIS layer, augmented with interactive access to enable the user to inspect the respective attributes. Each and any combination of these layers can be superimposed on user-selectable digital elevation models of Greece and surrounding areas. For the layers that include data publicly available by third parties, their associated metadata can be accessed through the Atlas web-page (with due reference to the source). Atlas has been developed with respect to the INSPIRE 2007/2/ΕΚ EU Directive, which urges stakeholders to ensure easy access to detailed data and metadata for all public and private sectors, free of charge, or at a cost covering the maintenance of data sets and related data services.The various thematic layers were constructed using the ArcGIS Pro v2.6.2 software. All data are in WGS 1984 Geographic Coordinate System, integraded into an interactive Web App, available at http://www.geophysics.geol.uoa.gr/atlas.html.

2.1. Active Faults: The NOA Database (NOAFaults)

The first edition of the “NOAFaults” database of active faults was published by [2]. The new Seismotectonic Atlas incorporates an updated second edition of the database [3][4]. The active fault database was constructed with material extracted from at least 110 scientific papers published in international journals as of 1972 and has proven to be useful to many researchers or practitioners of the civil engineering community and public authorities.

The active faults were digitized from the original fault maps that were published in peer-review journals at various cartographic scales. Inside the database there is a field in the fault attribute table that is called “location reliability” with three (3) classifications (precise, approximate and inferred) depending on the cartographic scale used in the digitization (1:50,000, 1:50,000–1:250,000 and above 1:250,000, respectively). The fault trace geometry is in agreement with the right-hand rule in seismology (i.e., a fault strike of 110° indicates a fault striking ESE-WNW and dipping to the south). In all cases, the fault attributes are those provided in the original papers; when missing, a value of 60° for a typical normal fault and a rake angle of −90° for the orientation of the slip vector was inserted. We noted that the “NOAFaults” database does not currently consider the seismogenic part of the subducting African (oceanic) plate where most reverse-slip earthquakes originate.

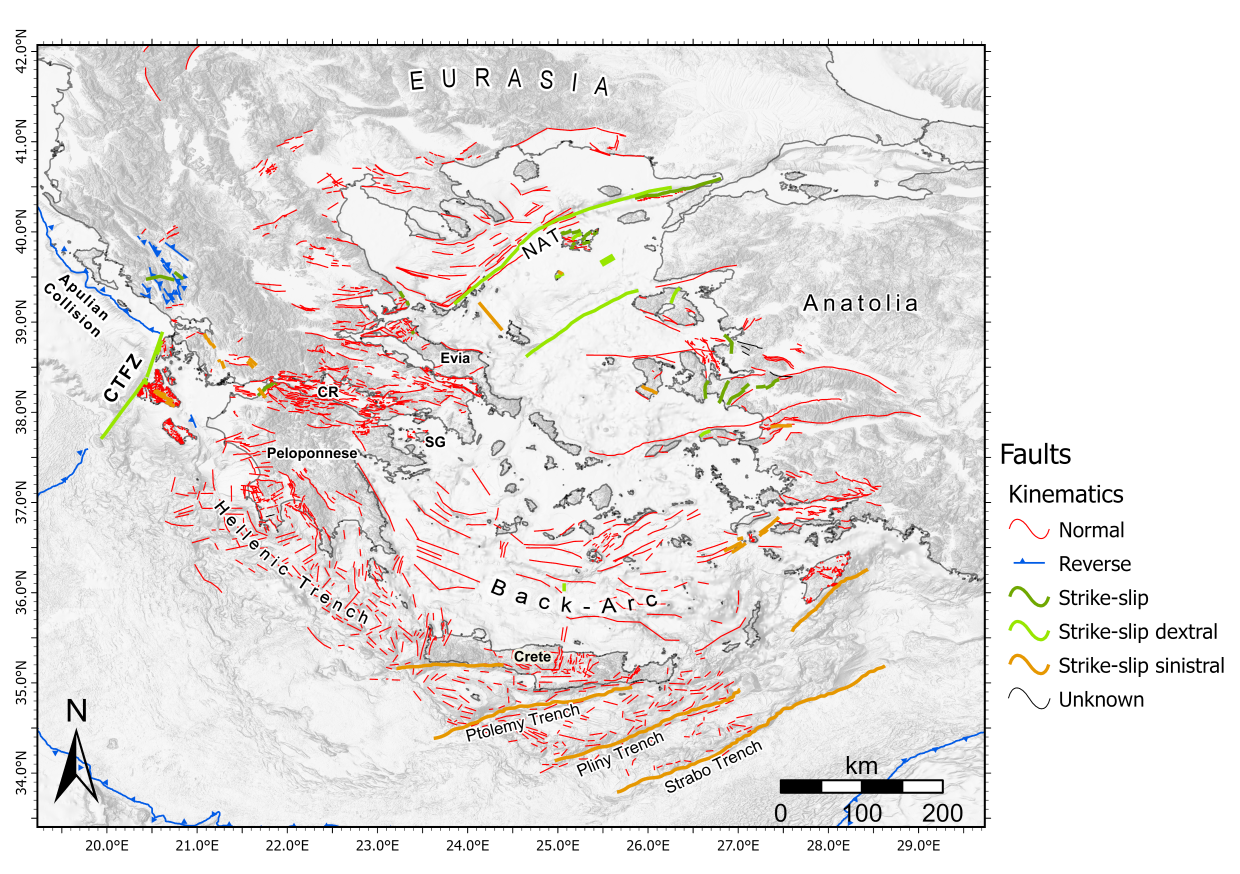

Each entry (fault) in the database contains information on the geometry of the fault, its strike, dip direction and dip angle, the type of rupture and, wherever possible, the kinematics of the rupture. The fault database is shown in Figure 1 and can be imported to GIS programs or used as input for other applications and queries. For well-studied faults [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13], the database also reports the long-term slip rates (or its creep) and/or the co-seismic slip of the last earthquake to have taken place. In this first version of the Atlas, we focus on the active faults of the Aegean and Eurasian plates and the back-arc region of the Hellenic Arc (2437 entries). Of those, 95% exhibit normal, 3% strike-slip and only 1% reverse faulting. The published literature information has permitted the correlation between epicenters of strong seismic events with the location of active faults, thus identifying the seismic fault for 57 strong events. The magnitude of those events ranges from Mw 5.0 to 7.4. The fault database shows that almost 50% of active faults is longer than 5 km and, therefore, comprise a moderate to high risk level when these faults cross or lie in the vicinity of urban areas.

Figure 1. The database of active faults in the broader Greek region [3][4]. Lines indicate their surface traces, with colors representing each fault’s kinematics. CTFZ: Cephalonia Transform Fault Zone, NAT: North Aegean Trough, CR: Corinth Rift, SG: Saronikos Gulf, SAVA: South Aegean active Volcanic Arc. Magenta dashed line depicts the approximate Eurasia-Africa plate boundary along the Hellenic Subduction Zone (HSZ).

The fault length and rupture type data can be used for the estimation of the maximum expected magnitude and average co-seismic displacement, using appropriate empirical relationships [14][15][16]. This type of information is very useful in planning the use of land and in designing infrastructures and critical facilities close to, or across active faults. Finally, the fault database, in combination with the seismicity, focal mechanism, stress/strain and other databases of the Atlas, could be used for rupture and hazard forecasting, with the incorporation of additional information and with appropriate geoprocessing tools [17][18][19]. Such capabilities will be included in future editions of the Atlas.

2.2. Volcanism and Plutonism

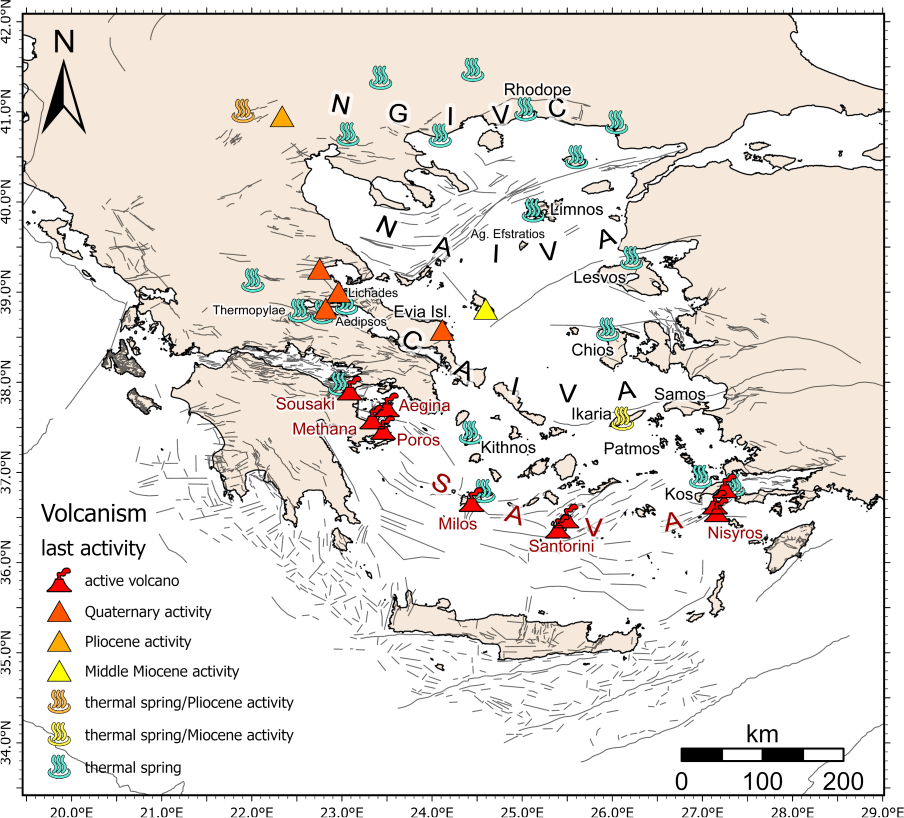

Volcanic activity in Greece is not very frequent. Nevertheless, given historical destructive eruptive episodes, it has to be taken into account in modern multi-hazard assessment since numerous Quaternary to Holocene volcanic centers exist throughout the Greek territory (Figure 2). Several authors posit that this is due to south-westward migration of the volcanic centers caused by the rollback of the subducting African plate [20][21][22]. The most significant features related to volcanic activity are shown in Figure 2 as follows:

-

The Hellenic Volcanic Arc, a.k.a. South Aegean active Volcanic Arc (SAVA) of Plio-Quaternary age. Extensive and detailed information can be found in the topical volume edited by [23]. It extends from Sousaki/Methana in the west, to Milos and Santorini in the center and Nisyros to the east, and is characterized by calc-alkaline and high-K calc-alkaline activity (Figure 2).

-

The Central Aegean inactive Volcanic Arc (CAIVA) of Late Miocene age, with volcanic centers, ostensibly identified at Chios, Ikaria, Samos, Patmos and Central Evia islands [24][25].

-

The N. Aegean inactive Volcanic Arc (NAIVA) of Oligocene-Lower Miocene age with calc-alkaline volcanic centers, ostensibly identified at Limnos, Agios Efstratios and Lesvos islands [26][27][28].

-

The Northern Greece inactive Volcanic Centers (NGIVC) of Eocene-Oligocene age at Rhodope, mainly composed of felsic igneous rocks such as granites [26][29].

The western terminus of the SAVA is a broad volcanic field, consisting of the Sousaki, Aegina, Poros and Methana volcanic centers (Figure 2), all attributed to Pliocene calc-alkaline volcanism. Recent geochemical and geophysical studies have shown that magmas resulted from the upwards migration of fluids in the asthenospheric mantle wedge [30][31][32]. At present, Sousaki is a low-intensity solfatara, whereas Aegina and Poros are practically extinct. The only remaining major active element of the field is the Methana volcanic terrain. Activity may have begun during the late Pliocene [33][34] and built the volcanic edifice through the Pleistocene and Quaternary in several phases (seven according to [34]). The last significant eruption took place circa 238 BCE and effused lava that flowed up to 500 m north-northwest of the coastline; it was mentioned by Pausanias (who also described the post-eruptive thermal activity), Strabo and Ovid. The most recent noteworthy paroxysmic activity was a small-scale submarine effusion in 1700 CE, approximately 2 km N-NW of the 238 BCE eruption (at the so-called Pausanias submarine volcano). It has been argued [34] that tectonic activity is closely knit with the inception and evolution of the volcano in a top-down sense. This has been confirmed [35], and it has also been demonstrated that all recent (eruptive and non-eruptive) activity is completely controlled by contemporary tectonics.

The central SAVA is composed of the Santorini Volcanic Complex, Milos Island and Christiana (islets SW of Santorini) volcanic fields, all associated with tholeiitic and calc-alkaline magmatism. Featuring a high temperature geothermal field, Milos is a presently dormant stratovolcano; the most recent significant activity there was related to a series of phreatic eruptions between 380 and 90 Ka ago [36][37], although other studies propose younger ages [38]. Phreatic explosions, commonly producing overlapping craters of usually sub-kilometric diameter, continued from the late-Pleistocene to recent times. A lahar deposit in south-east Mílos, buried the walls of a Roman harbor town and is thought to have originated from a small phreatic explosion.

The most significant volcanic field of SAVA is the Santorini Volcanic Complex (SVC), which came into being in the Middle Pleistocene. At least twelve eruptions of Plinian intensity have taken place during the last 360 Ka. Each of those discharged material volumes of a few to several cubic kilometres and all together formed pyroclastic deposits, with a thickness of 200 m, containing relics of at least five large shield volcanoes. The intervals between Plinian eruptions average to 30 Ka. The explosive activity triggered at least four caldera collapses and resulted in the formation of the present-day composite caldera structure [39]. The last caldera-forming explosion was the renowned Minoan eruption of the late Bronze Age (1645–1500 BCE) [39][40][41]. Several significant submarine and sub-aerial paroxysms have occurred since, the last one taking place in 1950. The most recent activity occurred during 2011–2012 and was accompanied by crustal dilation and intense seismic activity [42][43]. The contemporary active tectonic modes of the SVC were recently clarified by [44], who illustrated their complete top-down control of the volcanism, and argued that it is physically shaped by tectonic rather than volcanic activity, including the form of the caldera.

The eastern terminus of the SAVA is characterized by several volcanic centers of Late Miocene-Pliocene age, the most important of which are the Nisyros and Kos islands. Kos is currently characterized by the complete absence of volcanic activity, while thermal manifestations are sparse and limited to a few low-temperature thermal springs. Nisyros, for which very extensive and thorough information can be found in the topical volume edited by [45], is still active. The volcano came into being at approximately 300 Ka BCE, with submarine extrusive activity that developed into subaerial dacitic and rhyodacitic after about 161 Ka BCE. A series of Plinian intensity eruptions accompanied by central caldera formation occurred between 44–24 Ka BCE. The post-caldera era began with the extrusion of the rhyolitic–dacitic magmas that cover the western part of the caldera (24 Ka BCE), followed by intermittent low intensity volcanic and continuous high intensity hydrothermal activity. At least eleven phreatic explosions have been reported between 1422 CE and 1888 CE, with the last of these episodes (1871–1873) accompanied by intense seismic activity and damage. The latest minor episode of unrest has taken place in 1996–1997. As evident from [45], local and regional tectonics has had a principal role in the inception and evolution of the volcano. Finally, it has been argued [46] that the contemporary thermal activity is completely controlled and guided by active faulting.

At the north of Evia Island and along an 80 km E-W stretch to the west, there are andesitic outcrops (Lichades islets, offshore the westernmost tip of Evia Island) and several major thermal springs which include the famous Thermopylae. All these are due to mainly plutonic calc-alkaline magmatism clearly identified by geophysical (magnetic anomaly) data and related to the SAVA system [30][45][46][47].

This dataset [48][49][50] could be used in assessing volcanic hazards such as volcanic earthquakes, pyroclastic flows and surges, lahars, debris avalanches, dome collapses, lava flows, tephra and ballistic projectile trajectories, volcanic gas hazards, volcanogenic tsunamis, etc.

Figure 2. The database of volcanic fields in the broader Greek region [48][49][50] with colors and different symbols denoting their age and type. Black lines are active faults [3][4].

2.3. Seismicity

Given that the probabilistic and semi-probabilistic (hybrid) assessment of earthquake threat is heavily dependent on the existence of a reliable seismic record, earthquake catalogues are essential in the appraisal of seismic hazard and the mitigation of earthquake disasters. Accordingly, we consider that the inclusion of this type of information in the new Seismotectonic Atlas of Greece, together with tools, currently under development, to assist in the analysis of seismic hazard, structural vulnerability and risk, is absolutely essential. In response, we compiled a unified earthquake catalogue of Greece and surrounding areas on the basis of seven different source catalogues spanning the period 1000 to June 2020 CE and available through different national and international agencies. This allowed us to assemble all the events that have been recorded during the late historical and instrumental eras and may have been included in some catalogues but not in others. The source catalogues are:

-

The SHARE European Earthquake Catalogue for the period 1000–1899 (SHEEC 1000–1899—https://www.emidius.eu/SHEEC/sheec_1000_1899.html);

-

The SHARE European Earthquake Catalogue for the period 1900–2006 (SHEEC 1900–2006—https://www.gfz-potsdam.de/sheec);

-

The MKK catalogue for the period 1900–2009 [51];

-

The ISC Bulletin for the period 1964–2017 [52];

-

The ISC-EHB catalogue for the period 1964–2016 [53];

-

The ISC-GEM catalogue for the period 1904–2016 [54];

-

The GI-NOA catalogue for the period of January–May 2018 (http://bbnet.gein.noa.gr/HL/databases/database);

-

The NKUA-SL (2020) catalogue for the period of June 2018–June 2020 (http://www.geophysics.geol.uoa.gr/stations/gmapv3_db/index.php?lang=en).

Because the original catalogues include different types of magnitude, we used the empirical formulae of [55][56] to convert mb, Ms, ML and Md to Mw. Table 1 presents the summary of the contents of each catalogue.

Table 1. Summary of contents of seismicity catalogues.

|

|

SHEEC 1000–1899 |

SHEEC 1900–2006 |

MKK |

ISC |

ISC-EHB |

ISC-GEM |

NOA |

NKUA-SL |

|

Events |

665 |

7706 |

7352 |

55075 |

2550 |

918 |

4737 |

30816 |

|

Period |

1000–1899 |

1900–2006 |

1901–2009 |

1964–2017 |

1964–2016 |

1904–2016 |

January–May 2018 |

June 2018–June 2020 |

|

Depth |

0–150 |

0–200 |

0–215 |

0–260 |

0–174 |

0-153 |

2–186 |

0–147 |

|

Mw |

4.6–8.3 |

4.0–7.7 |

4.1–7.6 |

2.3–7.5 |

4.6–7.6 |

5.0-7.7 |

1.0–5.2 |

1–6.8 |

Having converted all magnitudes to a unified Mw, we merged the catalogues, eliminated multiple records of the same events and added from the NKUA catalogue, all MW ≥ 3 events that occurred as of 1/1/2018. The priority (from high to low) in which we retained instrumental events from multiple records was: SHEEC, MKK, ISC-GEM, ISC-EHB and ISC bulletin, while the applied criteria for their detection was an origin time difference of up to 20 sec, epicentral distance less than 50 km and magnitude difference (in unified Mw) smaller than 0.5. Finally, we added all ML ≥ 3 from the NOA (January–May 2018) and NKUA-SL catalogues (June 2018 onwards) and also converted the magnitude to Mw. We generated a comprehensive seismicity catalogue covering the area of N33.0°–42.5°, E18°–33°. This is the Atlas Earthquake Catalogue and contains 116,268 events with MW = 2.7–8.3 at a focal depth range 0–263 km. The attributes of the seismicity database, include the date, time, location, depth and unified (average of the converted Mw magnitudes, in case the single or preferred source reports more than one type of magnitude). Generally speaking, the completeness of the catalogue is 5.8 for the period 1000–1899, drops to 5.2 between 1900 and 1963, then to approximately 4 during 1964–1989 and, finally, to 3.6 during the last 30 years (in the unified Mw scale). It is worth noting that seismicity has become spatially denser in particular after 2008 [57], when the various Greek seismological networks were integrated into the Hellenic Unified Seismological Network (HUSN) of broadband receivers.

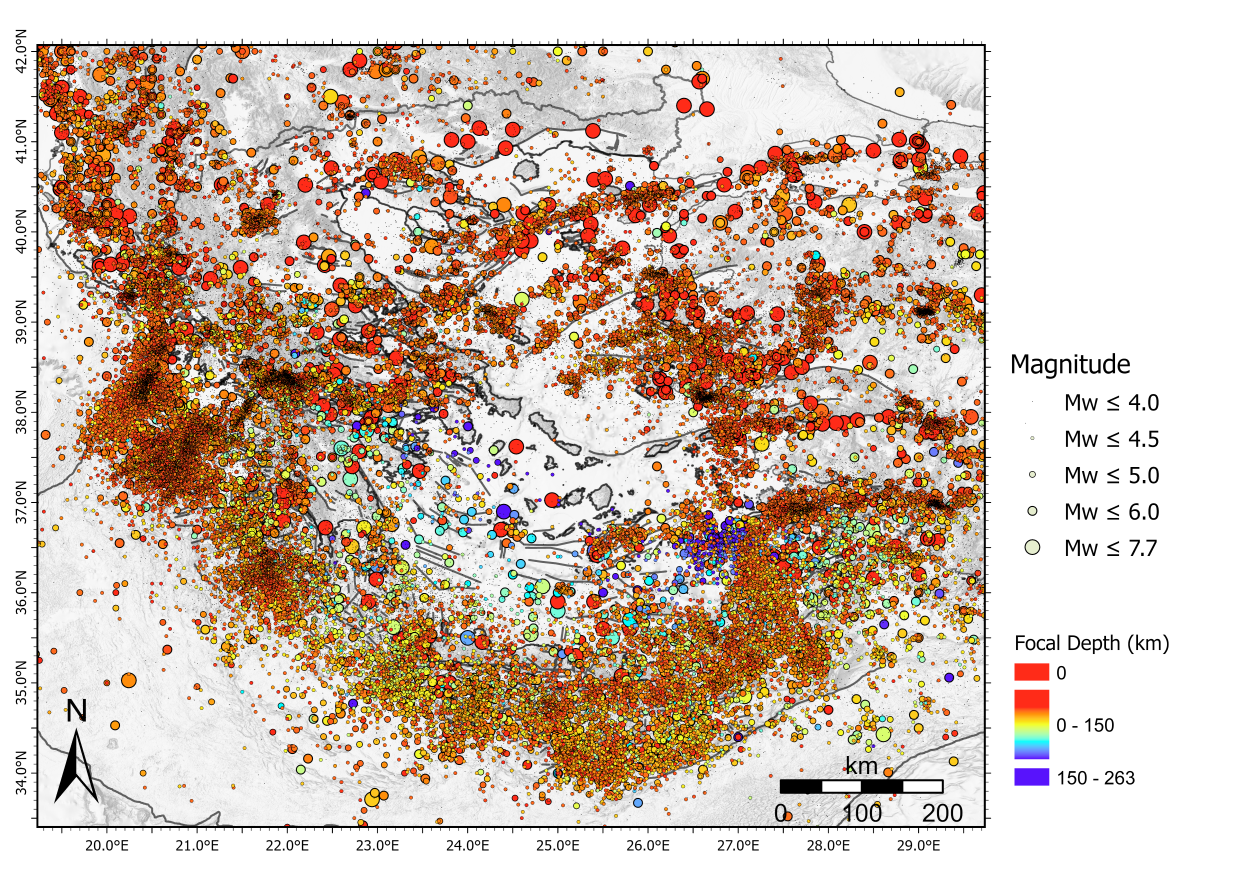

As can be seen in Figure 3 and the respective online Atlas application, the largest part of seismicity is crustal, at focal depths of less than 30 km, concentrated along major active seismic zones such as the Hellenic Arc, the N. Aegean Trough (NAT) and the Corinth Rift (CR). The NE and SE Aegean exhibit intense activity. Earthquake foci become progressively deeper as one moves from the front of the Hellenic Arc to the Aegean, demonstrating the activity of the north-easterly dipping Benioff zone of the Hellenic Subduction System (HSS). The central Aegean and northern Greece exhibit low seismicity rates.

Figure 3. Epicenter distribution of the Atlas Earthquake Catalogue. The Catalogue is unified but not complete and contains 116,268 events with MW ≥ 2.7 spanning the period 1000 CE to June 2020—see text for details.

Highest seismicity rates are observed along the CTFZ and the Hellenic Arc. The western part of the Hellenic Arc presents the major part of seismic energy release across the Greek territory. In particular the area of the CTFZ and offshore NW Peloponnese, which according to the European Seismic Hazard Model (ESHM-13) [58] is the most seismically prone area of Europe, has been often activated recently, producing strong and occasionally damaging earthquakes [59][60][61][62][63][64][65]. An interesting feature is a NE-SW boundary of seismicity between the CTFZ and Zakynthos Island, marking an area that has been suggested to host a Subduction-Transform-Edge-Propagator (STEP) fault, due to a trench-perpendicular tearing of the slab [66][67][68][69][70], or a ramp-type structure [71][72] beneath the CTFZ, bridging NAT with the Hellenic Trench [73], possibly the margin between the continental and oceanic slab of the Hellenic Subduction System (HSS) [30][71][74]. This area is well-known for transpressional tectonics [75][76], while the recent Mw6.7 earthquake on 25th October 2018 provided strong indications for seismic coupling in the western region of the Hellenic Arc with most of co-seismic deformation taken up by the upper (Aegean) plate [64], with a potentially significant effect for the regional seismic hazard.

Gaps of seismicity are aligned orthogonally to the western Hellenic Arc (N-E to N-S), extending from the south of CTFZ to central Crete, related to ~N-S normal faulting of the upper (Aegean) plate. Seismicity gaps are observed only in the part of the Hellenic Arc where N-S normal faulting occurs. The easternmost seismicity gap occurs in an area where faulting rotates from ~N-S to ~E-W. These seismicity gaps could be explained by slab tears perpendicular to the western Hellenic Arc [77][89], allowing extensive subcrustal convection/flux from the mantle wedge [30][71]. However, the seismic gap, located offshore south Peloponnese and western Crete, is probably due to the low earthquake detectability of the seismological networks.

East of central Crete, seismicity appears continuous, distributed in a WNW-ESE direction, related to E-W and NE-SW normal faults. East of Crete, a NNW-SSE structure, perpendicular to the Hellenic Arc bounds dense shallow seismicity to its west and sparser one, mainly subcrustal to the east. This area is suggested to be related to a STEP fault beneath the western coast of the south Anatolian plate, separating the Hellenic Subduction Zone (HSZ) from the western Cyprus Subduction Zone (CSZ) [67][78][79][80], or horizontal tearing of the slab that likely explains the presence of a NW dipping slab [81]. This NNW-oriented seismicity boundary is in agreement with [74], who suggest slab segmentation east of Crete, with the eastern segment dipping with a steeper angle compared to the western one. Despite the importance of the pattern for the regional geodynamics, the new seismicity catalogue indicates that deep seismic sources mainly control the seismic hazard of this area. East of HSZ, seismicity is sparser, clustered, distributed in a NE-SW direction, along the southern margin of the hydrothermal field of west Anatolia [48][49][50].

Instrumental subcrustal seismicity, located at depths greater than 100 km, highlights the amphitheatrically-shaped SAVA north of the convergence front of North Africa and Aegean. Subcrustal earthquakes coexist with crustal seismicity in the SAVA, with the major seismicity rates observed east of the SVC, mainly due to the recent unrest of Santorini volcano during 2011–2012 [41], and the M6.6 Kos earthquake on 20 July 2017 [82]. A prominent feature highlighted from seismicity is a 55 km long concentration of shallow events along the Amorgos fault that produced a catastrophic tsunamigenic event in 1956 with M7.7, the largest magnitude observed in the Aegean during the instrumental era [83][84]. To the West of the SVC, seismicity is sparse. However, an increase in seismic activity is observed at the westernmost tip of SAVA, in the region of Methana volcano and Saronikos Gulf, monitored after April 2016 [85]. This phenomenon should be taken under consideration with respect to a likely increase of seismic hazard in the Athens metropolitan area, the center of which lies less than 50 km away from the activated region. In this respect, it should be noted that Athens was recently struck by an Mw = 5.1 event on 19 July 2019 [86][87], which reactivated part of the structure that had hosted the Mw = 6.0 earthquake of 7 September 1999 [88].

Central Aegean appears aseismic, while E-W structures offshore west Anatolia and along the Corinth Rift are delineated by seismicity at these latitudes, signature of the Late Cenozoic evolution of the Aegean [89]. In North Aegean, seismicity indicates major E-W to NE-SW structures related to the westward extrusion of North Anatolia in the Aegean. This area has been often activated during the last years, producing strong earthquakes at times damaging for the nearby islands [90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99], with the most recent destructive one having occurred offshore southern Lesvos Island on 12th June 2017 [98][99]. The epicenters distribution of the compiled catalogue does not imply continuation of these strike-slip structures in continental Greece, where the most active structure is the Corinth Rift, and in particular its western part. On the contrary, major active NW-SE-oriented structures, such the one that produced the 2001 M6.4 Skyros earthquake [91][92][93], Evia Island and the Corinth Rift likely constitute barriers for the western propagation of NAT.

West of Corinth Rift, the aseismic Cephalonia-Lefkada-Acarnania Block (CLAB) is evidenced, a tectonically complex area bounded by transpressional and transtensional structures [75][76][100][101]. North of CLAB the main part of seismicity is distributed beneath NW Greece and Albania, mostly associated with thrust faulting [75][101][102][103]. East of Amvrakikos Gulf, seismicity is related to normal faulting, therefore, a continuation of NAT within continental Greece is likely not supported by seismic activity. Clustered seismicity in continental Greece is mainly related to seismic sequences and particularly those monitored by local temporary networks.

2.4. Focal Mechanisms, Stress and Strain-Rate Field

Focal mechanisms are essential in understanding the seismotectonic setting of an area and, together with seismicity, are necessary for the definition of seismic sources to be used in seismic hazard assessment. In this section, we present the catalogue of double-couple earthquake focal mechanisms, used in the new Seismotectonic Atlas, together with the stress field derived therefrom by formal inversion.

The new Atlas currently incorporates the catalogue of [104], containing 1322 crustal seismic events with focal depths between 0 and 30 km and magnitudes between M = 4.0 and M = 7.4, for the period 1902–January 2017. This catalogue is an update of the one by [100], and includes reliable solutions obtained by moment tensor inversion or first motion polarities, where moment tensor solutions were not available. It is compiled by thorough research of the international literature (theses, books, journals, conference proceedings, catalogues from [105] and catalogues of international seismological institutions such as NKUA (http://www.geophysics.geol.uoa.gr), NOA (http://bbnet.gein.noa.gr), EMSC (http://www.emsc-csem.org), ISC (http://www.isc.ac.uk), GCMT (http://www.globalcmt.org) and RCMT (http://rcmt2.bo.ingv.it/). The catalogue also includes reliable focal mechanisms constrained by aftershock sequences and swarms [97][99][100][106][107][108][109][110][111].

In cases of duplicate events, a “preferred” solution was chosen by expert judgment, based on the compliance of a focal mechanism with known local and regional geodynamics and the precision of its hypocentral location [100]. The majority of post-2008 focal mechanisms correspond to events located using recordings of the HUSN. However, a large number of events have been relocated using different local and regional crustal velocity models, each optimized so as to yield improved hypocentral locations for earthquakes recorded (primarily) by local networks, as well as by the HUSN [100].

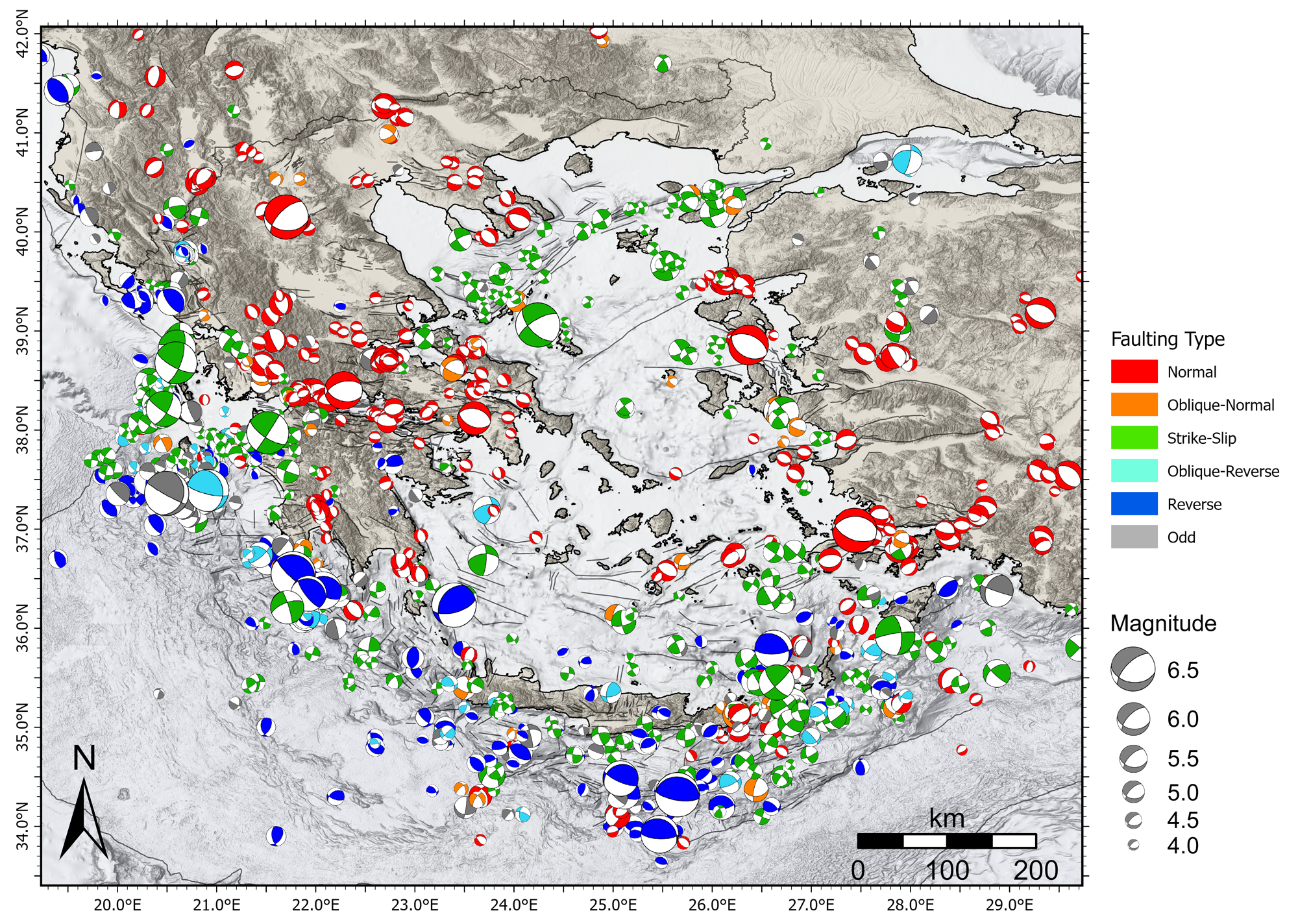

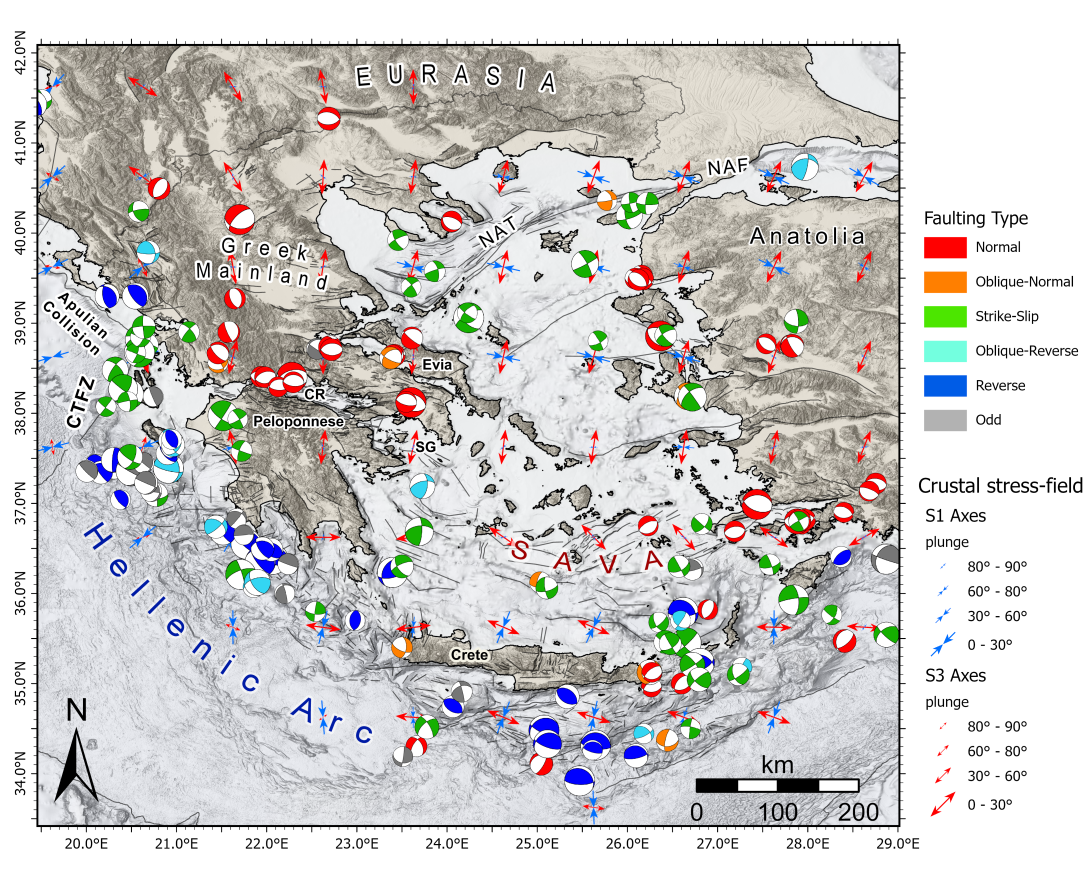

Figure 4 presents the distribution of the focal mechanisms, color-coded according to the type of rupture following the classification criteria of [112]. The type of rupture according to the focal mechanisms is generally consistent with the type of rupture registered in the active faults database (see Section 2.1; Figure 2). Specifically, normal faulting predominates in the Greek mainland and along the eastern Aegean island and the western coast of Turkey, thrust faulting predominates in the Hellenic Arc and the Apulian collision front (NW Greece–W Albania). Finally, strike-slip faulting is the main type of rupture along the CTFZ and NW Peloponnese, the N. Aegean Trough and southeastern boundary of the Aegean and African plates (Strabo and Pliny trenches; see Figure 2). Focal mechanisms indicate transpressional tectonics along the Hellenic Arc and transtensional across the overriding Aegean plate. The attributes of the focal mechanism database include the location, magnitude (Mw), strike, dip and rake for both nodal planes, the trend and plunge of the principal moment tensor axes, the slip vectors, the faulting type according to [112] and the bibliographic source of each entry. In addition, the Atlas currently includes a layer with focal mechanisms of significant earthquakes at both shallow and intermediate focal depths for the period 1995–June 2020 from the database of NKUA-SL.

Figure 4. Focal mechanisms for crustal earthquakes (z ≤ 30 km) with M ≥ 4.0. Beach balls are color-coded according to Zoback’s classification scheme [112]. Data from the database of NKUA-SL.

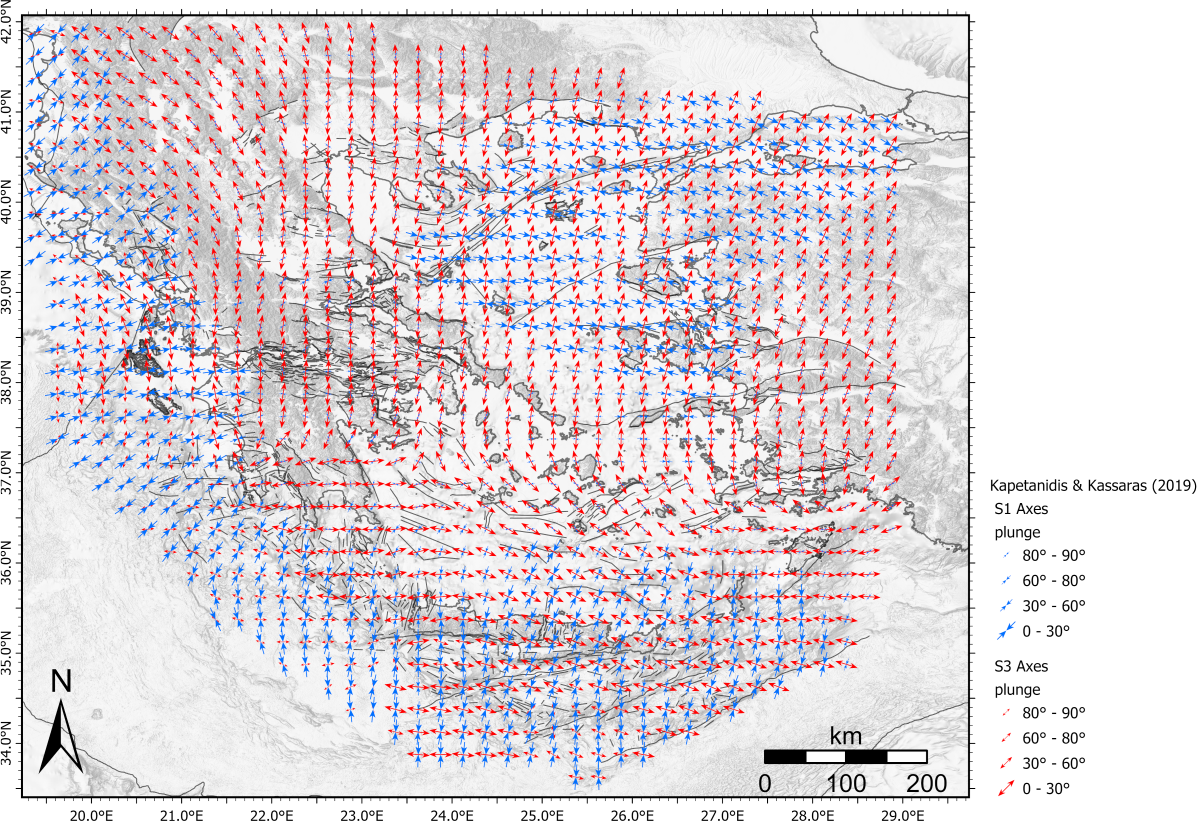

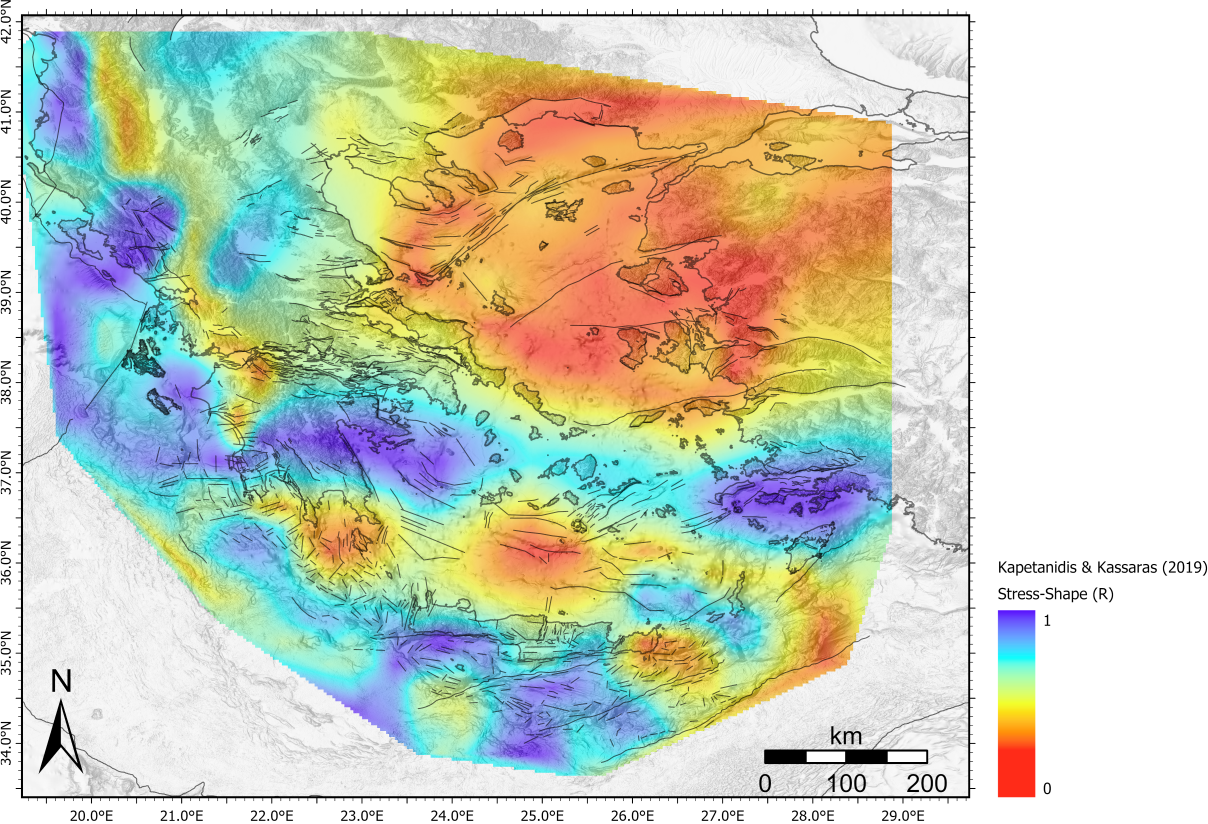

The determination of the stress field is important for the assessment of a region’s seismotectonic setting and associated seismic hazard. The inversion of focal mechanisms of earthquakes is a robust procedure, which in combination with strain-rates deduced from satellite geodesy and tectonic field observations, can provide constraints on the three-dimensional (3D) deformation of the crust [100]. Using the focal mechanism database and implementing a least-squares approach, based on the Wallace-Bott hypothesis [113] that faults slip in the direction of the maximum shear stress on the fault plane, the contemporary stress-field of Greek territories and surrounding areas has been computed in a grid of 0.25° × 0.25° cells (Figures 6–8). As described in the inversion was performed using a damped least-squares approach, with the assumption of stress uniformity within each individual cell while, simultaneously, minimizing differences between neighboring cells. In summary:

-

The distribution of the stress field is consistent with the faulting style observed for major faults.

-

Transtensional stress is observed in the Aegean, the Corinth Rift and W. Greece.

-

Transpressional stress predominates in NW Greece, the Hellenic Arc and Crete.

-

In the Aegean, the SAVA roughly marks a zone of transition, across which the stress field rotates by 90°: The S1 axis changes from almost E–W to the north of approximately 36.5° N to almost N–S to the south of that parallel. It also coincides with a sharp contrast in the crustal stress-shape (Figure 6) and a deflection in the orientation of SKS and Rayleigh wave anisotropy [43; references therein]. An analogous transition can be observed in the Peloponnese relative to approximately 37° N, with the difference that field there is mainly N-S extensional to the north of this parallel and mainly E-W extensional to the south; this effect is highlighted by high stress-shape values R = 1 − (σ2 − σ3)/(σ1 − σ3), where σ1, σ2, σ3 are the magnitudes of the principal stress axes, with σ1 > σ2 > σ3).

-

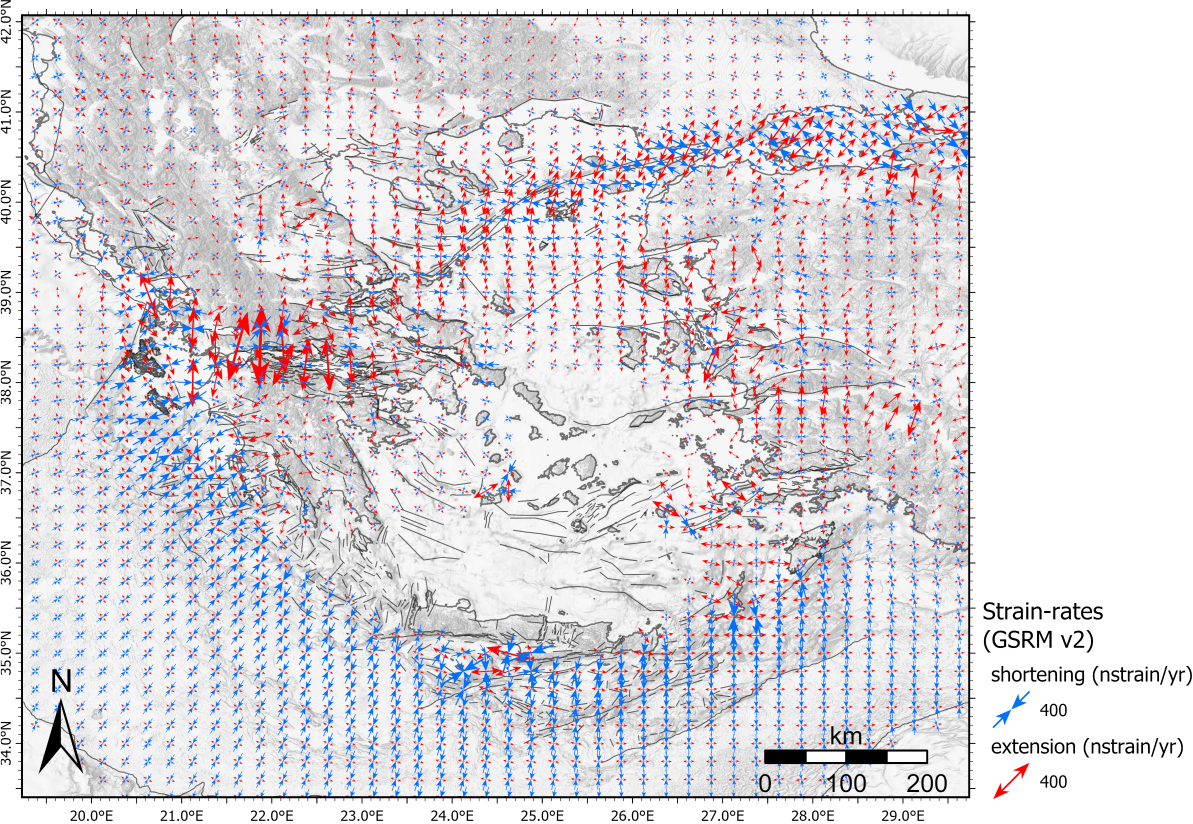

These abovementioned observations are in good agreement with the strain-rate field of the Global Strain Rate Model [114]. Surface Strain Rate (SSR; Figure 7) appears compatible with seismicity (Figure 3). High shortening rate is observed along the Hellenic Arc, whereas high extensional deformation rate is observed along a line that connects CTF and NW Peloponnese with NAT, an area that has been suggested to constitute the boundary between the continental and oceanic slab of the HSS [30][71]. An interesting implication is the consistency between stress and strain-rate, regarding the inferred faulting type, particularly apparent in areas of complex tectonics, i.e., transpressional or transtensional. Low strain-rate can be observed at regions where the seismicity is also low, i.e., in central Aegean and northern Greece (see also Figure 3).

Figure 5. Crustal stress field derived from the inversion of earthquake focal mechanisms [104]. Blue and red arrows indicate major (S1), and minor principal stress axes (S3), respectively. Black lines are active faults [3][4].

Figure 6. Crustal stress shape, R = 1 − (σ2 − σ3)/(σ1 − σ3), derived from the inversion of earthquake focal mechanisms [104]. Black lines are active faults [3][4].

Figure 7. Surface Strain-Rate (SSR) [114]. Black lines are active faults [3][4].

2.5. Tsunamis

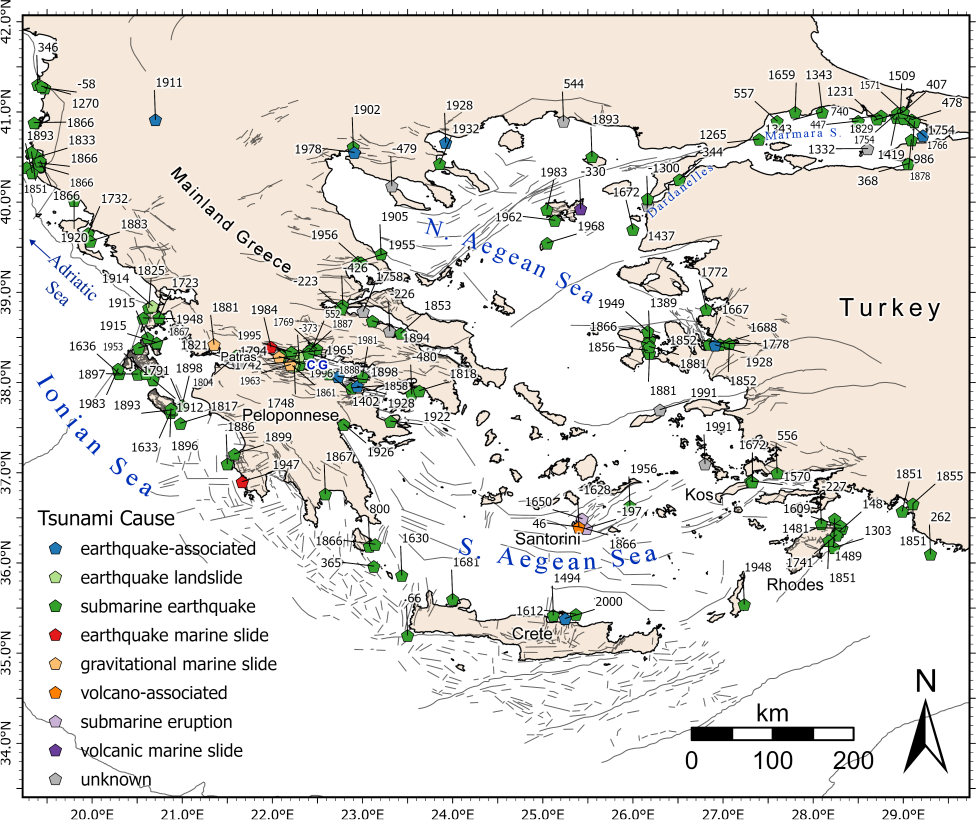

The new Seismotectonic Atlas of Greece contains the tsunami catalogue of [115]. This includes 162 events, starting with the late Bronze Age (Minoan eruption of Santorini volcano) and ending with a sea-level oscillation observed at Heraklion, Crete, in year 2000 CE. Information for each entry of the catalogue is derived from original historical documents, previous tsunami catalogues, scientific reports, studies and books and, in a few cases, from field observations made by [115]. Of this dataset, we chose to include 160 events that have been associated with geographic coordinates (Figure 8; also see Table 2 for the general characteristics).

Table 2. Characteristics of the tsunami database included in the Atlas. RI: Reliability Index (RI—Rel_2 field in the Atlas database).

|

Number of Events |

160 |

RI |

Counts |

|

Period |

1628 BCE–2000 CE |

1 |

22 |

|

Latitude Range |

35.2° N–42.6° N |

2 |

33 |

|

Longitude Range |

18.1° E–29.3° E |

3 |

60 |

|

Region |

Greece and adjacent areas |

4 |

45 |

The attributes of each event in the original tsunami database [115], include the ID number, the time of occurrence, the Reliability Index (RI) of the time of occurrence, the region (M1 = Greek and adjacent regions in the European Tsunami Catalogue), the originating event, the location of the originating event in geographic coordinates, the RI of that location, a short description of the event, the intensity (I0) in the Modified Mercalli Intensity scale, the surface-wave magnitude (Ms) and the focal depth of the originating event (if the tsunami was caused by an earthquake), the Volcanic Explosivity Index of the originating event (if the tsunami was caused by a volcanic eruption), the maximum vertical tsunami run-up (in cm), the Tsunami Intensity (TI) in the scale of [116], its respective RI and, finally, an index showing if the tsunami parameters were revised (Y) or not (N) in reference to previous source catalogues.

In terms of the reliability of the tsunami events, a modified version of the tsunami reliability scale of [117] was adopted (0 = very improbable tsunami, 1 = improbable, 2 = questionable, 3 = probable, 4 = definite). Events assigned with a reliability index of 0 were not included in the database. Some others, described as sea disturbances or sea-quakes, were included with a reliability of 1 or 2, if it was not certain that the event was not a tsunami.

Tsunami origins are classified in three main classes that include sub-classes: Class 1 includes earthquakes with subclasses ER (submarine earthquake), EA (earthquake associated), EL (earthquake-caused landslides), ES (earthquake-caused submarine landslides). Class 2 includes volcano paroxysms with subclasses VO (submarine eruption) VA (volcano-associated), VL (volcano-related landslides), VS (volcano-related submarine landslides). Class 3 includes only slumps, i.e., gravitational submarine slides (GS). The database contains 143 tsunamis related to earthquakes, 5 related to volcanic activity and 3 related to slumps (Table 3 and Figure 8).

Table 3. Tsunami classification according to their source. See text for discussion.

|

Cause |

Counts |

Cause |

Counts |

Cause |

Counts |

|

Earthquake |

143 |

Volcanic Activity |

5 |

Slumps |

3 |

|

EA |

8 |

VO |

3 |

GS |

3 |

|

EL |

4 |

VA |

1 |

|

|

|

ER |

129 |

VL |

0 |

|

|

|

ES |

2 |

VS |

1 |

|

|

Figure 8. Tsunami locations shown with colored pentagons, indicating the cause of the tsunami (see text and Table 3 for explanation). The year of occurrence is also indicated. Data from [115]. Black lines are active faults [3][4].

As evident in Figure 8, 23 tsunami events are located inside the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles, 19 in the gulfs of Corinth and Patras, 15 around Rhodes and SW Turkey, 19 across the western Peloponnese and the central Ionian Sea, and 13 in the south Adriatic Sea; these are associated with shallow, strong (M6+) earthquakes. Recent events, such as the M6.5 Lefkada earthquake of 2015 [62], the M6.6 Kos earthquake of 2017 [82] and the M6.7 Zakynthos event of 2018 [64], confirmed the recurrence of tsunamis in the Dodecanese and the central Ionian Sea. Overall, it appears that significant tsunamis are frequent in Greece and its surrounding areas, and that the accurate mapping of tsunami occurrence is important for both academic research and for tsunami disaster management.

2.6. Magnetic Field

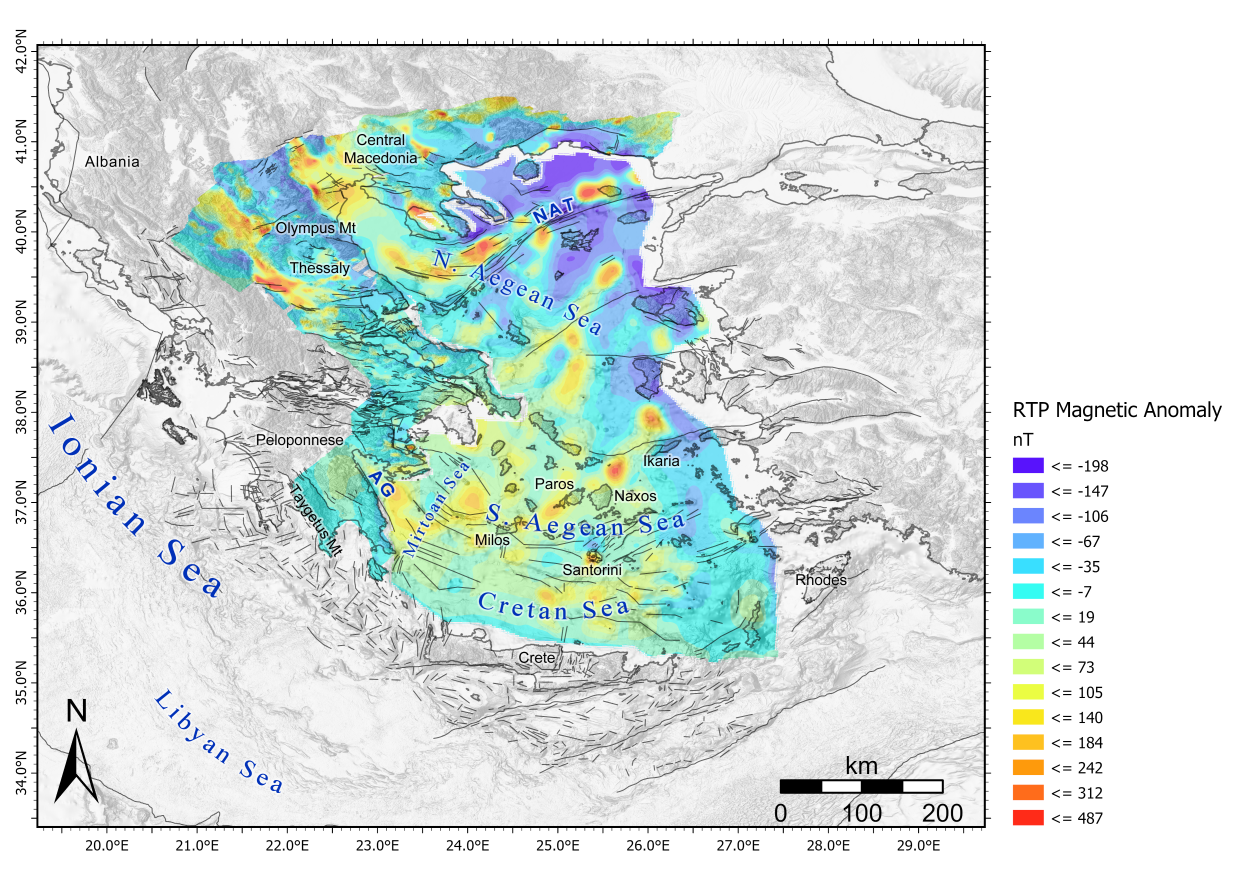

The onshore elements of the unified and homogeneous magnetic anomaly map of Greece are based on the 1:50,000 aeromagnetic map series of IGME, produced by ABEM AB and Hunting Geology and Geophysics Ltd. Details can be found in [118][119]. The ABEM maps [120] were produced with measurements at a nominal constant ground clearance (CGC) of 275 ± 75 m above ground level (AGL). Flight line (track) direction was NE-SW with a mean distance (spacing) of 1 km between tracks. Connection (tie) lines for crossover adjustment were also flown in a NE-SW direction, with a mean inter-track distance of 10 km. Hunting Geology and Geophysics Ltd. has generally used a measurement spacing of 200–250 m and has flown in a NE-SW direction but at different CGC and track densities. These would be 150 m AGL at 400 m spacing in areas of known massive ultramafic rock outcrops and 300 m AGL at 800 m spacing otherwise. The high mountainous zones Olympus in Thessaly/Central Macedonia and Taygetus in the Southern Peloponnese were surveyed at constant elevations of 3000 m and 2300 m above mean sea level (AMSL) respectively, with 1000 m track spacing in both cases. In all cases, connection lines were flown in a NE-SW direction and a spacing of 10 km. The IGRF (International Geomagnetic Reference Field) correction was based on the IGRF model for the epoch 1977.3. A constant value of 150 nT was added to the magnetic anomaly values before plotting the contour maps. The offshore elements were extracted from the magnetic anomaly maps of [121], spanning the north and south Aegean, Mirtoan Sea and large parts of the Cretan seas.

The original map sheets were converted to high-resolution raster images and digitized to vector form in image coordinates. Using the corners of the map sheets as control points, the image coordinates were geo-located and transformed to Cartesian in the UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator) projection. The digitized data was finally interpolated to a rectangular grid with uniform spacing of 250 m and collated to generate Digital Magnetic Anomaly Models, one for each survey area and data collection scheme. For Hunting data, the arbitrary 150 nT value was removed from the grids. In the case of onshore data, the IGRF model of epochs 1977.3 (Hunting survey) and 1966.5 (ABEM survey) was re-calculated at 0 m elevation and added to the grids. Thus, the original total intensity measurements were reproduced as representatively as possible. Next, the Digital Magnetic Anomaly Models were re-computed, this time by subtracting the Definite IGRF for the corresponding epochs and CGC’s of each magnetic anomaly model; calculations were performed on the basis of the 3 arcsec Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) digital elevation model. The improvement in the accuracy of the magnetic anomalies afforded by this reprocessing scheme is significant and ranges from a few nT to several tens of nT at low elevation areas [122]. In a final step, the mosaic of magnetic anomaly models was “homogenized” by referral to the common CGC of 1300m AGL/AMSL. This entailed field continuation between arbitrary surfaces and was carried out with the equivalent sources method of [123]. The details of the procedure can be found in [124]. The continued Magnetic Anomaly Models were subsequently collated and reduced to the pole (RTP) to generate the map shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. The RTP Magnetic Anomaly Map, upward continued to a constant elevation of 1300 m. Fault lines are after [3][4]. AG: Argolic Gulf, NAT: North Aegean Trough.

The principal sources of high-amplitude magnetic responses in mainland Greece are ophiolite sequences that are clearly observed in Macedonia and Thessaly (zonal NW-SE trending anomalies). In the rest of the mainland, magnetic anomalies are more or less local and generated by large near-surface ophiolitic, olistolites and olistostromes embedded in tectonic mélange, or by dismembered ophiolite complexes emplaced by alpine thin-skinned tectonics. Accordingly, they do not stand out at the elevation and scale of Figure 9. The most remarkable observation, however, is the abundance and intensity of marine magnetic anomalies, the most reasonable explanation of which is widespread (calc-alkaline) plutonic magmatism. The alignments of such anomalies can clearly be observed along the North Aegean Trough (NAT), in the Central Aegean, across the NE Peloponnese (Mirtoan Sea—Argolic Gulf), along the Ikaria—Naxos—Paros—Milos line in the South Aegean Sea and along the northern margin of the Cretan Sea. In all cases, magmatism develops either directly along, or adjacent to crustal-scale dislocation surfaces that can be strike-slip, oblique-normal or normal fault zones. A number of studies along the SAVA have also demonstrated that magma emplacement and thermal fluid circulation is directly associated with contemporary active faulting, and specifically at the intersection of regional-scale fault zones [29][33][42]. This would imply that earthquake and volcanic hazards are causally related and in the grand scheme of things, it might be possible to improve the appraisal of volcanic risks by detailed monitoring of tectonic deformation in the broader areas of major volcanic fields.

2.7. Gravity Field

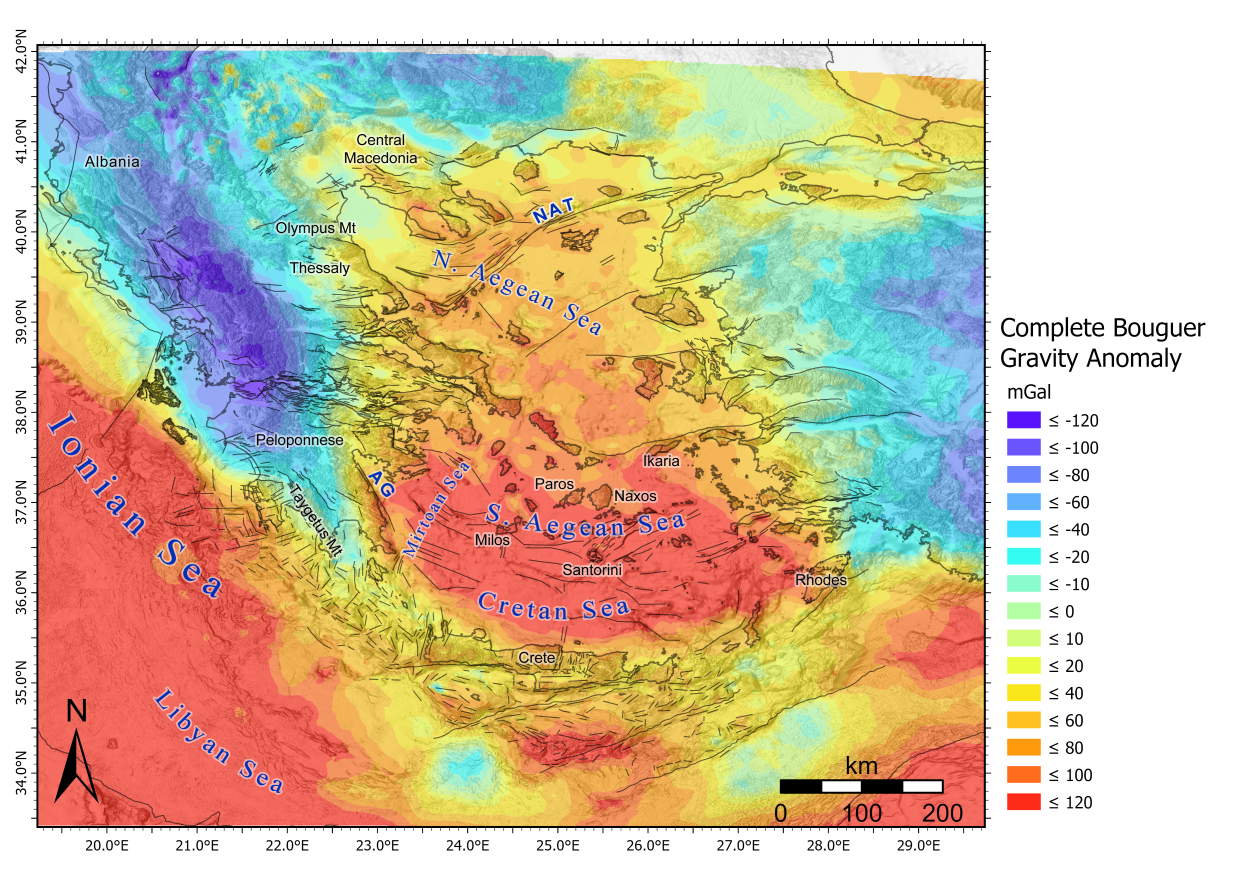

The Gravity Anomalies Map of the region is based on the data included in the Gravity Data Bank (UoA-GDB), compiled at the Section of Geophysics & Geothermics by [124]. The number of gravity stations in the UoA-GDB was originally 33,000 points; these have been augmented with data collected from a variety of sources, so that the present count is approximately 290,000. All these have undergone a procedure of homogenization that reduced the datasets from different sources to a common reference (datum), and included recalculation of the free-air, Bouguer and terrain corrections on the basis of common digital elevation models. The calculations were carried out using vertical prisms with the algorithm originally described by [125][126], as modified by to calculate the gravity effect of topography on a spherical Earth. After applying the necessary reductions, the standard Bouguer anomaly was calculated using a density 2.67 gr/cm3. The terrain corrections were calculated to a radius of 167 km around each gravity station. For land data, a detailed 100 m DEM was used for radii up to 22 km around the station and a coarse 1 km DEM for radii between 22 and 167 km. On the basis of the final homogeneous data bank, and depending on the density of gravity stations, local and regional gravity anomaly maps can be produced by interpolation, to the desired level of detail: the regional complete Bouguer anomaly map shown in Figure 10 is based on a 1 × 1 km grid. The map clearly shows the mode of crustal thickening as one moves from the abyssal plains of the oceanic African crust (Ionian Sea, Libyan Sea and Eastern Mediterranean) into the continental crust of the Aegean plate, and the subsequent thinning of the backarc region (Cretan sea—Aegean Sea). In the Southern Aegean area the gravity signal of the dipping African Slab is also detectable.

Figure 10. The complete Bouguer Anomaly Map. Fault lines are after [3][4]. AG: Argolic Gulf, NAT: North Aegean Trough.

2.8. Isostatic Anomalies

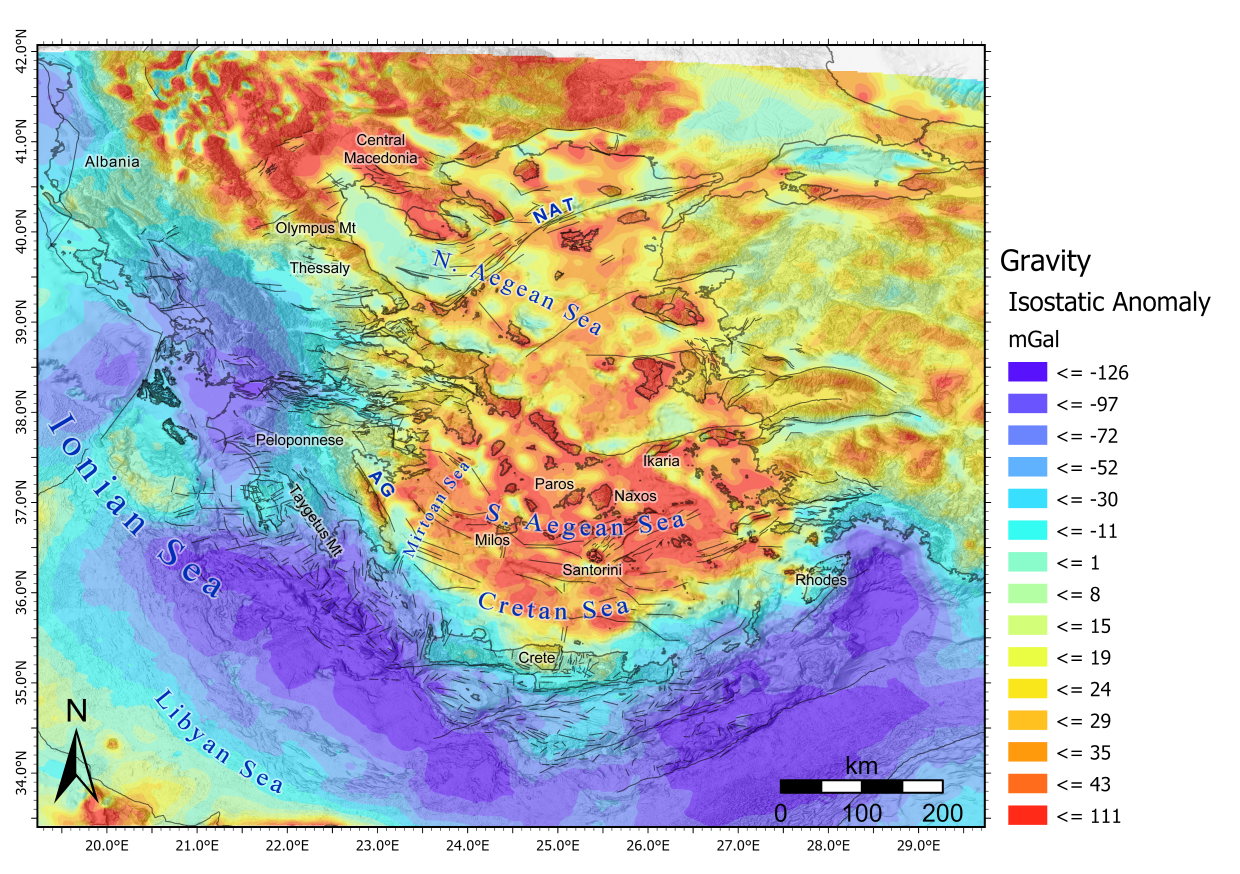

The theory of Isostasy explains the response of the Earth’s crust to the gravitational load exerted by changes in topography (topographic load). The quantification of this response is based on isostatic models, and its application to the complete Bouguer anomaly (isostatic correction) generates the isostatic anomaly. At regional (hectokilometric) scales, isostatic anomalies expose the presence (or lack thereof) uncompensated or overcompensated topographic loads. At local (kilometric/decakilometric) scales, isostatic anomalies enhance the expression of density contrasts due to geology and tectonics. In a tectonically active realm, both results are useful in the context of a seismotectonic Atlas. Regional isostatic anomalies provide information related to the geodynamics, as well as to “deep” structures connected with crustal-scale tectonics and seismicity. Local isostatic anomalies illustrate the geometric relationship between the shape of geological structures and active tectonics, as the latter is expressed by active fault lineaments and/or seismicity. Previous studies [123][124][125][126] indicated that the best fitting Airy model computed on the basis of our data is one with a mean crustal depth of 25 km. Subsequent unpublished validation tests have led to similar conclusions. Accordingly, the application of isostatic corrections based on this model to the Bouguer anomaly map of Figure 10, generated the isostatic anomaly map of Figure 11, which is the version incorporated in the new Seismotectonic Atlas.

Figure 11. The Isostatic Anomaly Map. Fault lines are after [3][4]. AG: Argolic Gulf, NAT: North Aegean Trough.

3. Summary

Knowledge and visualization of the present-day relationship between earthquakes, active tectonics and crustal deformation is a key to understanding geodynamic processes, and is also essential for risk mitigation and the management of geo-reservoirs for energy and waste. The study of the complexity of the Greek tectonics has been the subject of intense efforts of our working group, employing multidisciplinary methodologies that include detailed geological mapping, geophysical and seismological data processing using innovative methods and geodetic data processing, involved in surveying at various scales. The data and results from these studies are merged with existing or updated datasets to compose the new Seismotectonic Atlas of Greece. The main objective of the Atlas is to harmonize and integrate the most recent seismological, geological, tectonic, geophysical and geodetic data in an interactive, online GIS environment. To demonstrate the wealth of information available in the end product, herein, we present thematic layers of important seismotectonic and geophysical content, which facilitates the comprehensive visualization and first order insight into seismic and other risks of the Greek territories. The future prospect of the Atlas is the incorporation of tools and algorithms for joint analysis and appraisal of these datasets, so as to enable rapid seismotectonic analysis and scenario-based seismic risk assessment.

Figure 12. Τhe main seismotectonic features of the Greek territory. Blue and red arrows indicate trend and plunge of the major (S1) and minor (S3) principal stress axes. Focal mechanisms with Mw ≥ 5.0 from the database of NKUA-SL are presented, with colour corresponding to faulting type. CTFZ: Cephalonia Transform Fault Zone, NAT: North Aegean Trough, NAF: North Anatolian Fault, CR: Corinth Rift, SG: Saronikos Gulf, SAVA: South Aegean active Volcanic Arc.

With a view to improve the appraisal of earthquake hazard, risk and damage, the introduction of GIS and other tools will enable the extraction of data from any combination of databases (thematic layers) and their joint statistical analysis and interpretation. Deterministic and/or probabilistic (or hybrid) methods of Seismic Hazard Assessment (SHA) at regional and local scale will be facilitated in terms of data detail and completeness. It is important that the databases be updated on a regular basis for the new Seismotectonic Atlas of Greece to remain state-of-the-art. This could likely be ensured by systematic updates of informative layers by the SL-NKUA and by collaboration with third parties.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/geosciences10110447

References

- IGME (Institute of Geological and Mining Research). Seismotectonic Map of Greece; Scale 1:500,000; IGME: Athens, Greece, 1989.

- Ganas, A.; Oikonomou, I.; Tsimi, C. NOAfaults: A digital database for active faults in Greece. BGSG 2013, 47, 518–530, doi:10.12681/bgsg.11079.

- Ganas, A.; Tsironi, V.; Kollia, E.; Delagas, M.; Tsimi, C.; Oikonomou, A. Recent upgrades of the NOA database of active faults in Greece (NOAFAULTs). In Proceedings of the 19th General Assembly of WEGENER, Grenoble, France, 10–13 September 2018.

- Ganas, A. NOAFAULTS KMZ layer Version 2.1 (2019 update) (Version V2.1) [Data set]. Zenodo 2019, doi:10.5281/zenodo.3483136.

- Ganas, A.; Roberts, G.P.; Memou, T. Segment boundaries, the 1894 ruptures and strain patterns along the Atalanti Fault, Central Greece. J. Geodyn. 1998, 26, 461–486, doi:10.1016/S0264-3707(97)00066-5.

- Pavlides, S.B.; Valkaniotis, S.; Ganas, A.; Keramydas, D.; Sboras, S. The Atalanti active fault: Re-evaluation using new geological data. BGSG 2004, 36, 1560–1567, doi:10.12681/bgsg.16545.

- Ganas, A.; Pavlides, S.B.; Sboras, S.; Valkaniotis, S.; Papaioannou, S.; Alexandris, G.A.; Plessa, A.; Papadopoulos, G.A. Active Fault Geometry and Kinematics in Parnitha Mountain, Attica, Greece. J. Struct. Geol. 2004, 26, 2103–2118, doi:10.1016/j.jsg.2004.02.015.

- Ganas, A.; Pavlides, S.; Karastathis, V. DEM-based morphometry of range-front escarpments in Attica, Central Greece, and its relation to fault slip rates. Geomorphology 2005, 65, 301–319, doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2004.09.006.

- Karamitros, I.; Ganas, A.; Chatzipetros, A.; Valkaniotis, S. Non-planarity, scale-dependent roughness and kinematic properties of the Pidima active normal fault scarp (Messinia, Greece) using high-resolution terrestrial LiDAR data. J. Struct. Geol. 2020, 136, 104065, doi:10.1016/j.jsg.2020.104065.

- Kokkalas, S.; Pavlides, S.; Koukouvelas, I.; Ganas, A.; Stamatopoulos, L. Paleoseismicity of the Kaparelli fault (eastern Corinth Gulf): Evidence for earthquake recurrence and fault behaviour. Boll. Soc. Geol. Ital. 2007, 126, 387–395.

- Palyvos, N.; Pavlopoulos, K.; Froussou, E.; Kranis, H.; Pustovoytov, K.; Forman, S.L.; Minos‐Minopoulos, D. Paleoseismological investigation of the oblique‐normal Ekkara ground rupture zone accompanying the M 6.7–7.0 earthquake on 30 April 1954 in Thessaly, Greece: Archaeological and geochronological constraints on ground rupture recurrence. JGR 2010, 115, B06301, doi:10.1029/2009JB006374.

- Jackson, J.; McKenzie, D. A hectare of fresh striations on the Arkitsa fault, Central Greece. J. Struct. Geol. 1999, 21, 1–6.

- Koukouvelas, I.; Stamatopoulos, L.; Katsonopoulou, D.; Pavlides, S. A palaeoseismological and geoarchaeological investigation of the Eliki fault, Gulf of Corinth, Greece. J. Struct. Geol. 2001, 23, 531–543, doi:10.1016/S0191-8141(00)00124-3.

- Wells, D.L.; Coppersmith, K.J. New empirical relationships among magnitude, rupture width, rupture area, and surface displacement. BSSA 1994, 84, 974–1002.

- Ambraseys, N.N.; Jackson, J.A. Faulting associated with historical and recent earthquakes in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Geophys. J. Int. 1998, 133, 390–406, doi:10.1046/j.1365-246X.1998.00508.x.

- Pavlides, S.; Caputo, R. Magnitude versus faults’ surface parameters: Quantitative relationships from the Aegean Region. Tectonophysics 2004, 380, 159–188, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2003.09.019.

- Parsons, T. Recalculated probability of M ≥ 7 earthquakes beneath the Sea of Marmara, Turkey. JGR 2004, 109, B05304, doi:10.1029/2003JB002667.

- Ganas, A.; Parsons, T.; Segou, M. Fault-based Earthquake Rupture Forecasts for Western Gulf of Corinth, Greece. In Proceedings of the AGU 2014 Fall Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 15–19 December 2014.

- Murru, M.; Akinci, A.; Falcone, G.; Pucci, S.; Console, R.; Parsons, T. M ≥ 7 earthquake rupture forecast and time‐dependent probability for the sea of Marmara region, Turkey. JGR 2016, 121, 2679–2707, doi:10.1002/2015JB012595.

- Jacobshagen, V.; Diirr, S.; Kockel, F.; Kopp, K.-O.; Kowalczyk, G. Structure and geodynamic evolution of the Aegean Region. In Alps, Apennines, Hellenides; Closs, H., Roeder, D., Schmidt, K., Eds.; Schweizerbart: Stuttgart, Germany, 1978; pp. 537–564.

- Kahle, H.G.; Cocard, M.; Peter, Y.; Geiger, A.; Reilenger, R.; Barka, A.; Veis, G. GPS-derived strain rate field within the boundary zones of the Eurasian, African, and Arabian Plates. JGR 2000, 105, 23353–23370, doi:10.1029/2000JB900238.

- Papanikolaou, D.; Bargathi, H.; Dabovski, C.; Dimitriu, R.; El-Hawat, A.; Ioane, D.; Kranis, H.; Obeidi, A.; Oaie, G.; Seghedi, A.; et al. TRANSMED Transect VII: East European Craton–Scythian Platform–Dobrogea–Balkanides–Rhodope Massif–Hellenides–East Mediterranean–Cyrenaica. In The TRANSMED Atlas. The Mediterranean Region from Crust to Mantle; Cavazza, W., Roure, F., Spakman, W., Stampfli, G., Ziegler, P., Eds.; Spinger: Berlin, Germany, 2004.

- Fytikas, M.; Vougioukalakis, G. (Eds.) The South Aegean Volcanic Arc: Present Knowledge and future perspectives. In Developments in Volcanology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; p. 398; ISBN 9780444520463.

- Fytikas, M.; Innocenti, F.; Manetti, P.; Mazzuoli, R.; Peccerillo, A.; Villari, L. Tertiary to Quaternary evolution of volcanism in the Aegean region. The Geological Evolution of the Eastern Mediterranean. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 1985, 17, 687–699.

- Mountrakis, D. The Pelagonian zone in Greece. A polyphase-deformed fragment of the Cimmerian continent and its role in the geotectonic evolution of the eastern Mediterranean. J. Geol. 1986, 94, 335–347.

- Kouli, M.; Seymour, K. Plagioclase Microtextures and their importance for magma chamber dynamics-examples from Lesvos, Hellas and Teide, Canary Islands. NeuesJahrbuch Mineral. Mh. 2006, 182, 323–336, doi:10.1127/0077-7757/2006/0054.

- Kitsopoulos, K. Immobile trace elements discrimination diagramms with zeolitized volcaniclastics from the Evros—Thrace—Rhodope Volcanic Terrain. BGSG 2010, 43, 2455–2464, doi:10.12681/bgsg.11647.

- Pe-Piper, G.; Piper, D.J.W. The Igneous Rocks of Greece. The Anatomy of an Orogen. Beitr. Reg. Geol. Erde 2002, xvi, 573, doi:10.1017/S0016756803218021.

- Tzanis, A.; Efstathiou, A.; Chailas, S.; Stamatakis, M. Evidence of recent plutonic magmatism beneath Northeast Peloponnesus (Greece) and its relationship to regional tectonics. Geophys. J. Int. 2018, 212, 1600–1626, doi:10.1093/gji/ggx486.

- Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Papadimitriou, P. Deep structure of the Hellenic lithosphere from teleseismic Rayleigh-wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 221, 205–230, doi:10.1093/gji/ggz579.

- Dietrich, V.; Gaitanakis, P. Geological Map of Methana Peninsula (Greece); ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 1995.

- Pe-Piper, G.; Piper, D.J.W. The effect of changing regional tectonics on an arc volcano: Methana, Greece. J. Volcanol. 2013, 260, 146–163, doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2013.05.011.

- Tzanis, A.; Efstathiou, A.; Chailas, S.; Lagios, E.; Stamatakis, M. The Methana Volcano–Geothermal Resource, Greece, and its relationship to regional tectonics. J. Volcanol. 2020, 404, 107035, doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2020.107035.

- Fytikas, M.; Giuliani, O.; Innocenti, F.; Kolios, N.; Manetti, P.; Mazzuoli, R. The Plio-Quaternary volcanism of Saronikos area (western part of the active Aegean volcanic Arc). Ann. Geol. Pays. Hell. 1986, 33, 23–45.

- Vougioukalakis, G.; Fytikas, M. Volcanic hazards in the Aegean area, relative risk evaluation, monitoring and present state of the active volcanic centers. Dev. Volcanol. 2005, 7, 161–183, doi:10.1016/S1871-644X(05)80037-3.

- Principe, C.; Arias, A.; Zoppi, U. Hydrothermal explosions on Milos: From debris avalanches to debris flows deposits. In The South Aegean Active Volcanic Arc: Present Knowledge and Future Perspectives International Conference; Book of Abstracts 95; Milos: Birmingham, AL, USA, 2003.

- Druitt, T.H.; Francaviglia, V. Caldera formation on Santorini and the physiography of the islands in the late Bronze Age. Bull. Volcanol. 1992, 54, 484–493, doi:10.1007/BF00301394.

- Druitt, T.H.; Mellors, R.A.; Pyle, D.M.; Sparks, R.S.J. Explosive volcanism on Santorini, Greece. Geol. Mag. 1989, 126, 95–126, doi:10.1017/S0016756800006270.

- Fytikas, M.; Kolios, N.; Vougioukalakis, G.E. Post-Minoan volcanic activity of the Santorini volcano, volcanic hazard and risk, forecasting possibilities. In Thera and the Aegean World III; Hardy, D.A., Keller, J., Galanopoulos, V.P., Flemming, N.C., Druitt, T.H., Eds.; The Thera Foundation: London, UK, 1990; Volume 2, pp. 183–198.

- Lagios, E.; Sakkas, V.; Novali, F.; Belloti, F.; Ferretti, A.; Vlachou, K.; Dietrich, V. SqueeSAR™ and GPS ground deformation monitoring of Santorini Volcano (1992–2012): Tectonic implications. Tectonophysics 2013, 594, 38–59, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2013.03.012.

- Papadimitriou, P.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Kaviris, G.; Voulgaris, N.; Makropoulos, K. The Santorini Volcanic Complex: A detailed multi-parameter seismological approach with emphasis on the 2011–2012 unrest period. J. Geodyn. 2015, 85, 32–57, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2014.12.004.

- Tzanis, A.; Chailas, S.; Sakkas, V.; Lagios, E. Tectonic deformation in the Santorini volcanic complex (Greece) as inferred by joint analysis of gravity, magnetotelluric and DGPS observations. Geophys. J. Int. 2020, 220, 461–489, doi:10.1093/gji/ggz461.

- Dietrich, V.J.; Lagios, E. (Eds). Nisyros Volcano: The Kos—Yali—Nisyros Volcanic Field; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55460-0.

- Tzanis, A.; Sakkas, V.; Lagios, E. Magnetotelluric Reconnaissance of the Nisyros Caldera and Geothermal Resource (Greece). In Nisyros Volcano: The Kos—Yali—Nisyros Volcanic Field; Dietrich, V.J., Lagios, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 203–225, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55460-0.

- Fytikas, M.; Kolios, N. Preliminary heat flow map of Greece. In Terrestrial Heat Flow in Europe; Cermak, V., Rybach, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1979; pp. 197–205, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-95357-6_20.

- Gioni-Stavropoulou, G. Inventory of thermal and mineral springs of Greece, I., Aegean Sea. In Hydrological and Hydrogeological Investigation Report No. 39; IGME: Athens, Greece, 1983. (In Greek)

- Karastathis, V.K.; Papoulia, J.; Di Fiore, B.; Makris, J.; Tsambas, A.; Stampolidis, A.; Papadopoulos, G.A. Deep structure investigations of the geothermal field of the North Euboean Gulf, Greece, using 3-D local earthquake tomography and Curie Point Depth analysis. J. Volcanol. 2011, 206, 106–120, doi:10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2011.06.008.

- Siebert, L.; Simkin, T. Volcanoes of the World: An Illustrated Catalog of Holocene Volcanoes and Their Eruptions, Smithsonian Institution, Global Volcanism Program Digital Information Series. GVP-3. 2002. Available online: http://www.volcano.si.edu (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Serpen, U.; Aksoy, N.; Tahir, O. 2010 to present status of geothermal energy in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 35th Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, CA, USA, 1–3 February 2010. Available online: https://pangea.stanford.edu/ERE/pdf/IGAstandard/SGW/2010/serpen.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Erkan, K. Geothermal investigations in western Anatolia using equilibrium temperatures from shallow boreholes. Solid Earth 2015, 6, 103–113, doi:10.5194/se-6-103-2015.

- Makropoulos, K.; Kaviris, G.; Kouskouna, V. An updated and extended earthquake catalogue for Greece and adjacent areas since 1900. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 1425–1430, doi:10.5194/nhess-12-1425-2012.

- International Seismological Centre (ISC). On-Line Bull. 2020, doi:10.31905/D808B830.

- Engdahl, E.R.; Di Giacomo, D.; Sakarya, B.; Gkarlaouni, C.G.; Harris, J.; Storchak, D.A. ISC‐EHB 1964–2016, an improved data set for studies of Earth structure and global seismicity. Earth Space Sci. 2020, 7, e2019EA000897, doi:10.1029/2019EA000897.

- ISC-GEM Earthquake Catalogue. International Seismological Centre, Pipers Lane, Thatcham, Berkshire, RG19 4NS, United Kingdom 2020, doi:10.31905/d808b825.

- Papazachos, B.C.; Papazachou, C.B. The Earthquakes of Greece; Ziti Editions: Thessaloniki, Greece, 1997; p. 304.

- Kaviris, G.; Papadimitriou, P.; Makropoulos, K. Magnitude Scales in Central Greece. BGSG 2007, 40, 1114–1124, doi:10.12681/bgsg.16838.

- Mignan, A.; Chouliaras, G. Fifty Years of Seismic Network Performance in Greece (1964–2013): Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Completeness Magnitude. SRL 2004, 85, 657–667, doi:10.1785/0220130209.

- Woessner, J.; Laurentiu, D.; Giardini, D.; Crowley, H.; Cotton, F.; Grünthal, G.; Valensise, G.; Arvidsson, R.; Basili, R.; Demircioglu, M.B.; et al. The 2013 European Seismic Hazard Model: Key components and results. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2015, 13, 3553–3596, doi:10.1007/s10518-015-9795-1.

- Papadimitriou, P.; Kaviris, G.; Makropoulos, K. The Mw=6.3 2003 Lefkada Earthquake (Greece) and induced transfer changes. Tectonophysics 2006, 423, 73–82, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2006.03.003.

- Papadimitriou, P.; Chousianitis, K.; Agalos, A.; Moshou, A.; Lagios, E.; Makropoulos, K.. The spatially extended 2006 April Zakynthos (Ionian Islands, Greece) seismic sequence and evidence for stress transfer, Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 190, 1025–1040, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05444.x.

- Ganas, A.; Cannavo, F.; Chousianitis, K.; Kassaras, I.; Drakatos, G. Displacements recorded on continuous GPS stations following the 2014 M6 Cephalonia (Greece) earthquakes: Dynamic characteristics and kinematic implications. Acta Geodyn. Geomater. 2015, 12, 5–27, doi:10.13168/AGG.2015.0005.

- Melgar, D.; Ganas, A.; Geng, J.; Liang, C.; Fielding, E.J.; Kassaras, I. Source characteristics of the 2015 Mw6.5 Lefkada, Greece, strike-slip earthquake. JGR 2017, 122, 2260–2273, doi:10.1002/2016JB013452.

- Kassaras, I.; Kazantzidou-Firtinidou, D.; Ganas, A.; Tonna, S.; Pomonis, A.; Karakostas, C.; Papadatou-Giannopoulou, C.; Psarris, D.; Lekkas, E.; Makropoulos, K. On the Lefkas (Ionian Sea) November 17, 2015 Mw=6.5 Earthquake Macroseismic Effects. J. Earthq. Eng. 2018, doi:10.1080/13632469.2018.1488776.

- Ganas, A.; Briole, P.; Bozionelos, G.; Barberopoulou, A.; Elias, P.; Tsironi, V.; Valkaniotis, S.; Moshou, A.; Mintourakis, I. The 25 October 2018 Mw= 6.7 Zakynthos earthquake (Ionian Sea, Greece): A low-angle fault model based on GNSS data, relocated seismicity, small tsunami and implications for the seismic hazard in the west Hellenic Arc. J. Geodyn. 2020, 137, 101731, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2020.101731.

- Papadimitriou, P.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Spingos, I.; Pavlou, K.; Kaviris, G.; Kassaras, I.; Sakkas, V.; Voulgaris, N. The 25 October, 2018 Zakynthos (Greece) earthquake: Seismic activity at the transition between a transform fault and a subduction zone. Geophys. J. Int. under review.

- Piromallo, C.; Morelli, A. P wave tomography of the mantle under the Alpine-Mediterranean area. JGR 2003, 108, 148–227, doi:10.1029/2002JB001757.

- Spakman, W.; Nolet, G. Imaging algorithms, accuracy and resolution in delay time tomography. In Mathematical Geophysics: A Survey of Recent Developments in Seismology and Geodynamics; Vlaar, N.J., Nolet, G., Wortel, M.J.R., Cloetingh, S.A.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1988; pp. 155–187, doi:10.1007/978-94-009-2857-2_8.

- Govers, R.; Wortel, M.J.R. Lithosphere tearing at STEP faults: Response to edges of subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2005, 236, 505–523, doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2005.03.022.

- Suckale, J.; Rondenay, S.; Sachpazi, M.; Charalampakis, M.; Hosa, A.; Royden, L.H. High-resolution seismic imaging of the western Hellenic subduction zone using teleseismic scattered waves. Geophys. J. Int. 2009, 178, 775–791, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04170.x.

- Royden, L.H.; Papanikolaou, D.J. Slab segmentation and late Cenozoic disruption of the Hellenic arc. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2011, 12, Q03010, doi:10.1029/2010GC003280.

- Halpaap, F.; Rondenay, S.; Ottemöller, L. Seismicity, deformation and metamorphism in the western Hellenic subduction zone: New constraints from tomography. JGR 2018, 123, 3000–3026, doi:10.1002/2017JB015154.

- Pearce, F.D.; Rondenay, S.; Sachpazi, M.; Charalampakis, M.; Royden, L.H. Seismic investigation of the transition from continental to oceanic subduction along the western Hellenic Subduction Zone. JGR 2012, 117, B07306, doi:10.1029/2011JB009023.

- Jolivet, L.; Faccenna, C.; Huet, B.; Labrousse, L.; Le Pourhiet, L.; Lacombe, O.; Lecomte, E.; Burov, E.; Denèle, Y.; Brun, J.-P.; et al. Aegean tectonics: Strain localisation, slab tearing and trench retreat, Tectonophysics 2013, 597–598, 1–33, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2012.06.011.

- Bocchini, G.M.; Brüstle, A.; Becker, D.; Meier, T.; van Keken, P.E.; Ruscic, M.; Papadopoulos, G.A.; Rische, M.; Friederich, W. Tearing, segmentation, and backstepping of subduction in the Aegean: New insights from seismicity. Tectonophysics 2018, 734–735, 96–118, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2018.04.002.

- Haddad, Α.; Ganas, A.; Kassaras, I.; Lupi, M. Seismicity and geodynamics of western Peloponnese and central Ionian Islands: Insights from a local seismic deployment. Tectonophysics 2020, 778, 228353, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2020.228353.

- Sachpazi, M.; Laigle, M.; Charalampakis, M.; Diaz, J.; Kissling, E.; Gesret, A.; Becel, A.; Flueh, E.; Miles, P.; Hirn, A. Segmented Hellenic slab rollback driving Aegean deformation and seismicity. GRL 2016, 43, 651–658, doi:10.1002/2015GL066818.

- Govers, R.; Fichtner, A. Signature of slab fragmentation beneath Anatolia from full-waveform tomography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2016, 450, 10–19, doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.014.

- van Hinsbergen, D.; Kaymakci, N.; Spakman, W.; Torsvik, T.H. Reconciling the geological history of western Turkey with plate circuits and mantle tomography. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 297, 674–686, doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2010.07.024.

- Biryol, C.B.; Beck, S.L.; Zandt, G.; Ozacar, A.A. Segmented African lithosphere beneath the Anatolian region inferred from teleseismic P-wave tomography. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 184, 1037–1057, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04910.x.

- Legendre, C.P.; Meier, T.; Lebedev, S.; Friederich, W.; Viereck-Götte, L. A shear wave velocity model of the European upper mantle from automated inversion of seismic shear and surface waveforms. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 191, 282–304, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05613.x.

- Faccenna, C.; Thorsten, B.W.; Auer, L.; Billi, A.; Boschi, L.; Brun, J.-P.; Capitanio, F.A.; Funiciello, F.; Horvàth, F.; Jolivet, L.; et al. Mantle dynamics in the Mediterranean. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 283–332, doi:10.1002/2013RG000444.

- Ganas, A.; Elias, P.; Kapetanidis, V.; Valkaniotis, S.; Briole, P.; Kassaras, I.; Argyrakis, P.; Barberopoulou, A.; Moshou, A. The July 20, 2017 M6.6 Kos Earthquake: Seismic and Geodetic Evidence for an Active North-Dipping Normal Fault at the Western End of the Gulf of Gökova (SE Aegean Sea). PAGEOPH 2019, 176, 4177–4211, doi:10.1007/s00024-019-02154-y.

- Papadimitriou, E.E.; Sourlas, G.; Karakostas, V.G. Seismicity variations in southern Aegean, Greece, before and after the large (Mw7.7) 1956 Amorgos earthquake due to the evolving stress. PAGEOPH 2005, 162, 783–804.

- Nomikou, P.; Hübscher, C.; Papanikolaou, D.; Farangitakis, P.G.; Ruhnau, M.; Lampridou, D. Expanding extension, subsidence and lateral segmentation within the Santorini—Amorgos basins during Quaternary: Implications for the 1956 Amorgos events, central-south Aegean Sea, Greece. Tectonophysics 2018, 722, 138–153, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2017.10.016.

- Karakonstantis, A.; Papadimitriou, P.; Millas, C.; Spingos, I.; Fountoulakis, I.; Kaviris, G. Tomographic imaging of the NW edge of the Hellenic volcanic arc. J. Seismol. 2019, 23, 995–1016, doi:10.1007/s10950-019-09849-8.

- Kouskouna, V.; Ganas, A.; Kleanthi, M.; Kassaras, I.; Sakellariou, N.; Sakkas, G.; Valkaniotis, S.; Manousou, E.; Bozionelos, G.; Tsironi, V.; et al. Evaluation of macroseismic intensity, strong ground motion pattern and fault model of the Athens 19/07/2019 Mw5.1 earthquake. J. Seismol. 2020, under review.

- Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Papadimitriou, P.; Pavlou, K.; Spingos, I.; Kaviris, G.; Voulgaris, N. The 19 July 2019 earthquake in Athens, Greece: A delayed major aftershock of the 1999 Mw = 6.0 event, or the activation of a different structure? J. Geodyn. 2020, 139, 101766, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2020.101766.

- Papadimitriou, P.; Voulgaris, N.; Kassaras, I.; Kaviris, G.; Delibasis, N.; Makropoulos, K. The Mw=6.0, 7 September 1999 Athens earthquake. Nat. Hazards 2002, 27, 15–33, doi:10.1023/A:1019914915693.

- Armijo, R.; Meyer, B.; King, G.C.P.; Rigo, A.; Papanastassiou, D. Quaternary evolution of the Corinth Rift and its implications for the Late Cenozoic evolution of the Aegean. Geophys. J. Int. 1996, 126, 11–53, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1996.tb05264.x.

- Benetatos, C.; Roumelioti, Z.; Kiratzi, A.; Melis, N. Source parameters of the M 6.5 Skyros island (North Aegean Sea) earthquake of July 26, 2001. Ann. Geophys. 2002, 45, 513–526, doi:10.4401/ag-3525.

- Papadopoulos, G.; Ganas, A.; Plessa, A. The Skyros earthquake (Mw6.5) of 26 July 2001 and precursory seismicity patterns in the North Aegean Sea. BSSA 2002, 92, 1141–1145. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/#abs/2002EGSGA..27.3710P/abstract (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Ganas, A.; Drakatos, G.; Pavlides, S.B.; Stavrakakis, G.N.; Ziazia, M.; Sokos, E.; Karastathis, V.K. The 2001 Mw = 6.4 Skyros earthquake, conjugate strike-slip faulting and spatial variation in stress within the central Aegean Sea. J. Geodyn. 2005, 39, 61–77, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2004.09.001.

- Rhoades, D.A.; Papadimitriou, E.E.; Karakostas, V.G.; Console, R.; Murru, M. Correlation of static stress changes and earthquake occurrence in the North Aegean Region. PAGEOPH 2010, 167, 1049–1066, doi:10.1007/s00024-010-0092-2.

- Karakostas, V.G.; Papadimitriou, E.E.; Tranos, M.D.; Papazachos, C.B. Active seismotectonic structures in the area of Chios Island, North Aegean Sea, revealed from microseismicity and fault plane solutions. BGSG 2010, XLIII, 2064–2074.

- Leptokaropoulos, K.M.; Papadimitriou, E.E.; Orlecka–Sikora, B.; Karakostas, V.G. Seismicity rate changes in association with evolution of the stress transfer in the Northern Aegean Sea, Greece. Geophys. J. Int. 2012, 188, 1322–1338, doi:10.1111/j.1365–246X.2011.05337.x, 2012.

- Ganas, A.; Roumelioti, Z.; Karastathis, V.; Chousianitis, K.; Moshou, A.; Mouzakiotis, E. The Lemnos 8 January 2013 (Mw = 5.7) earthquake: Fault slip, aftershock properties and static stress transfer modeling in the north Aegean Sea. J. Seismol. 2014, 18, 433–455, doi:10.1007/s10950-014-9418-3.

- Kiratzi, A.; Tsakiroudi, E.; Benetatos, C.; Karakaisis, G. The 24 May 2014 (Mw6. 8) earthquake (North Aegean Trough): Spatiotemporal evolution, source and slip model from teleseismic data. Phys. Chem. Earth 2016, 95, 85–100, doi:10.1016/j.pce.2016.08.003.

- Papadimitriou, P.; Kassaras, I.; Kaviris, G.; Tselentis, G.-A.; Voulgaris, N.; Lekkas, E.; Chouliaras, G.; Evangelidis, C.; Pavlou, K.; Kapetanidis, V.; et al. The 12th June 2017 Mw=6.3 Lesvos earthquake from detailed seismological observations. J. Geodyn. 2017, 115, 23–42, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2018.01.009.

- Kiratzi, A. The 12 June 2017 Mw 6.3 Lesvos Island (Aegean Sea) earthquake: Slip model and directivity estimated with finite-fault inversion. Tectonophysics 2018, 724, 1–10, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2018.01.003.

- Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A. On the spatial distribution of seismicity and the 3D tectonic stress field in western Greece. Phys. Chem. Earth 2016, 95, 50–72, doi:10.1016/j.pce.2016.03.012.

- Hatzfeld, D.; Kassaras, I.; Panagiotopoulos, D.; Amorese, D.; Makropoulos, K.; Karakaisis, G.; Coutant, O. Microseismicity and strain pattern in northwestern Greece. Tectonics 1995, 14, 773–785, doi:10.1029/95TC00839.

- Ganas, A.; Elias, P.; Briole, P.; Cannavo, F.; Valkaniotis, S.; Tsironi, V.; Partheniou, E.I. Ground Deformation and Seismic Fault Model of the M6.4 Durres (Albania) Nov. 26, 2019 Earthquake, Based on GNSS/INSAR Observations. Geosciences 2020, 10, 210. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/10/6/210/htm (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- Vannucci, G.; Gasperini, P. The new release of the database of earthquake mechanisms of the Mediterranean area (EMMA Version 2). Ann. Geophys. 2004, 47, 307–317, doi:10.4401/ag-3277.

- Kapetanidis, V.; Kassaras, I. Contemporary crustal stress of the Greek region deduced from earthquake focal mechanisms. J. Geodyn. 2019, 123, 55–82, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2018.11.004.

- Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Karakonstantis, A.; Kouskouna, V.; Ganas, A.; Chouliaras, G.; Drakatos, G.; Moshou, A.; Mitropoulou, V.; Argyrakis, P.; et al. Constraints on the dynamics and spatio-temporal evolution of the 2011 Oichalia seismic swarm (SW Peloponnesus, Greece). Tectonophysics 2014, 614, 100–127, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2013.12.012.

- Kiratzi, A.; Sokos, E.; Ganas, A.; Tselentis, A.; Benetatos, C.; Roumelioti, Z.; Serpetsidaki, A.; Andriopoulos, G.; Galanis, O.; Petrou, P. The April 2007 earthquake swarm near Lake Trichonis and implications for active tectonics in western Greece. Tectonophysics 2008, 452, 51–65, doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2008.02.009.

- Feng, L.; Newman, A.V.; Farmer, G.T.; Psimoulis, P.; Stiros, S.C. Energetic rupture, coseismic and post‐seismic response of the 2008 M W 6.4 Achaia‐Elia Earthquake in northwestern Peloponnese, Greece: An indicator of an immature transform fault zone. Geophys. J. Int. 2010, 183, 103–110, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04747.x.

- Karakostas, V.; Mirek, K.; Mesimeri, M.; Papadimitriou, E.; Mirek, J. The Aftershock Sequence of the 2008 Achaia, Greece, Earthquake: Joint Analysis of Seismicity Relocation and Persistent Scatterers Interferometry. PAGEOPH 2017, 174, 151–176, doi:10.1007/s00024-016-1368-y.

- Kapetanidis, V.; Papadimitriou, P. Estimation of arrival-times in intense seismic sequences using a Master-Events methodology based on waveform similarity. Geophys. J. Int. 2011, 187, 889–917, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2011.05178.x.

- Kapetanidis, V.; Deschamps, A.; Papadimitriou, P.; Matrullo, E.; Karakonstantis, A.; Bozionelos, G.; Kaviris, G.; Serpetsidaki, A.; Lyon-Caen, H.; Voulgaris, N.; et al. The 2013 earthquake swarm in Helike, Greece: Seismic activity at the root of old normal faults. Geophys. J. Int. 2015, 202, 2044–2073, doi:10.1093/gji/ggv249.

- Chouliaras, G.; Kassaras, I.; Kapetanidis, V.; Petrou, P.; Drakatos, G. Seismotectonic analysis of the 2013 seismic sequence at the western Corinth Rift. J. Geodyn. 2015, 90, 42–57, doi:10.1016/j.jog.2015.07.001.

- Zoback, M.L. First- and second-order patterns of stress in the lithosphere: The World Stress Map Project. JGR 1992, 97, 11703–11728, doi:10.1029/92JB00132.

- Bott, M.H.P. The mechanics of oblique slip faulting: Geol. Mag. 1959, 96, 109–117, doi:10.1017/S0016756800059987.

- Kreemer, C.; Blewitt, G.; Klein, E.C. A geodetic plate motion and Global Strain Rate Model. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2014, 15, 3849–3889, doi:10.1002/2014GC005407.

- Papadopoulos, G.A.; Tselentis, G.A.; Charalampakis, M. The Hellenic national tsunami warning center: Research, operational and training activities. BGSG 2016, 50, 1100–1109, doi:10.12681/bgsg.11815.

- Ambraseys, N.N. Data for the investigation of seismic sea waves in the Eastern Mediterranean. BSSA 1962, 52, 895–913.

- Iida, K. Catalog of Tsunamis in Japan and Its Neighbouring Countries; Dept. of Civil Engin., Aichi Institute of Technology: Toyohashi, Japan, 1984; p. 52.

- Chailas, S.; Tzanis, A.; Kranis, H.; Karmis, P. Compilation of a Unified and Homogeneous Aeromagnetic Map of the Greek Mainland. 12th Int. BGSG 2010, XLIII, 1919–1929.

- Chailas, S.; Tzanis, A. A new improved version of the Aeromagnetic Map of Greece. BGSG 2019, 7, 289–290. Available online: https://ejournals.epublishing.ekt.gr/index.php/geosociety/issue/view/1265 (accessed on 6 November 2020).

- ABEM. Final Report on an Airborne Geophysical Survey Carried out for the Greek Institute for Geology and Subsurface Research during the Year 1966; ABEM-AB Elektrisk Malmletning: Stockholm, Sweden, 1967.

- Pavlakis, P.; Makris, J.; Alexandrie, M. In Proceedings of the Marine Geophysical Mapping of Aegean Sea, 2nd International Congress, Hellenic Geophysical Union, Florina, Greece, 5–7 May 1993; pp. 400–411.

- Xia, J.; Sprowl, D.R.; Adkins-Heljeson, D. Correction of topographic distortions in potential-field data: A fast and accurate approach. Geophysics 1993, 58, 515–523.

- Chailas, S.; Hipkin, R.G.; Lagios, E. Isostatic studies in the Hellenides. Geophys. In Proceedings of the 2nd Congress of the Hellenic Geophysical Union, Florina, Greece, 5–7 May 1993; Volume 2, pp. 492–504.

- Lagios, E.; Chailas, S.; Hipkin, R.G. Gravity and topographic data banks of Greece. Geophys. J. Int. 1996, 126, 287–290, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1996.tb05287.x.

- Swain, C.J.; Aftab Khan, M. Gravity measurements in Kenya. Geophys. J. Int. 1978, 53, 427–429, doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1978.tb03750.x.

- Lagios, E. Gravity and Other Geophysical Studies Relating to the Crustal Structure of South-East Scotland. Ph.D. Thesis, Edinburgh University, Edinburgh, UK, 1979.