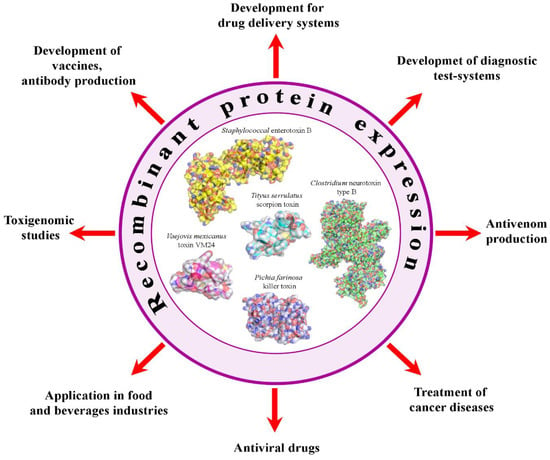

Toxins produced by various living organisms (bacteria, yeast, scorpions, snakes, spiders and other living organisms) are the main pathogenic factors causing severe diseases and poisoning of humans and animals. To date, recombinant forms of these toxins are widely used as antimicrobial agents, anticancer drugs, vaccines, etc. Various modifications, which in this case can be introduced into such recombinant proteins, can lead to a weakening of the toxic potency of the resulting toxins or, conversely, increase their toxicity. Thus, it is important to publicly discuss the situations and monitor the emergence of such developments.

- protein

- recombinant toxin

- antivenom

- vaccines

- killer toxins

- enzymatic antidots

1. Introduction

2. Spectrum of Recombinant Toxins and Their Origins

| Protein | Origin | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Production | ||

| BoNT | Bacteria Clostridium botulinum | [9] |

| Killer toxins K1, K28, K1L | Yeast Saccharomyces paradoxus | [10][11][12] |

| Killer toxin Kpkt | Yeast Tetrapisispora phaffii | [13][14] |

| ppa1, Tppa2, Tce3, Cbi1 | Scorpions of the genus Tityus and Centruroides | [15] |

| β/δ agatoxin-1 | Spider Agelena orientalis | [16] |

| Purotoxin-1 | Spiders of the genus Geolycosa sp. | [17] |

| Azemiopsin, Three-Finger Toxins | Viper Azemipos feae | [18][19] |

| MdumPLA2 | Coral snake Micrurus dumerilii | [20] |

| APHC3, HCRG21 | Sea anemone Heteractis crispa | [21][22] |

| Toxicity assays | ||

| C3bot, C3botE174Q, C2IIa | Bacteria Clostridium botulinum | [23][24][25] |

| LeTx | Bacteria Bacillus anthracis | [26] |

| HlyII | Bacteria Bacillus cereus | [27][28] |

| Cry1Ia | Bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis | [29] |

| BFT | Bacteria Bacterioides fragilis | [30] |

| EGFP-SbB, translocation domain (TD) of the diphtheria toxin |

Bacteria Corynebacterium diphtheriae | [31][32] |

| In1B | Bacteria Listeria monocytogenes | [33] |

| LcrV | Bacteria Yersinia pestis | [34] |

| AtaT2 | Bacteria Escherichia coli | [35] |

| Killer toxin Kpkt | Yeast Tetrapisispora phaffii | [36] |

| MeICT, KTx | Scorpion Mesobuthus eupeus | [37][38][39] |

| Tbo-IT2 | Spider Tibellus oblongus | [40] |

| α-conotoxins, α-cobratoxin | Marine snail and snake venom | [41] |

| Three-Finger Toxins | Viper Azemipos feae | [42] |

| α-neurotoxins | Cobra Naja melanoleuca | [43] |

| Hct-S3 | Sea anemone Heteractis crispa | [44] |

| Immunology assays | ||

| BoNT | Bacteria Clostridium botulinum | [45] |

| Beta and epsilon toxins | Bacteria Clostridium perfringens | [46][47] |

| Cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) | Bacteria Vibrio cholerae | [48] |

| Ancrod, batroxobin, RVV-V | Snakes Calloselasma rhodostoma, Bothrops atrox, Daboia russelii | [49][50] |

| Modifications | ||

| BoNT/B-MY, C2IN-C3lim | Bacteria Clostridium botulinum | [51][52] |

| DT389-YP7, s-DAB-IL-2(V6A), DT2219 | Bacteria Corynebacterium diphtheriae | [53][54][55] |

| rPA83m + plant virus spherical particles (SPs) | Bacteria Bacillus anthracis | [56][57][58] |

| SElP + Zn | Bacteria Staphylococcus aureus | [59] |

| PE38 + AgNP | Bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [60] |

| CTB-KDEL | Bacteria Vibrio cholerae | [61] |

| GFP-L2-AgTx2 | Scorpions Mesobuthus eupeus and Orthochirus scrobiculosus | [62] |

| LgRec1ALP1 | Spiders of the genus Loxosceles | [63] |

| Ms 9a-1 fragments and homologues | Sea anemone Metridium senile | [64] |

2.1. Bacterial Recombinant Toxins

2.2. Yeast Recombinant Toxins

2.3. Recombinant Toxins of Various Animals

2.4. Recombinant Prions

| Recombinant Protein | Purpose of Biosynthesis and Use | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| rPrP from a baculovirus-insect cell expression system (Bac-rPrP) | To determine whether Bac-rPrPSc is spontaneously produced in intermittent ultrasonic reactions | [69] |

| Mouse PrP (MoPrP, residues 89–230) in complex with a nanobody (Nb484) | To understand the role of the hydrophobic region in forming infectious prion at the molecular level | [70] |

| Transgenic mice expressing elk PrP (TgElk) | To test vaccine candidates against chronic wasting disease | [71] |

| rPrP from bank vole (BV rPrP) | To develop a method to dry and preserve the prion protein for long term storage | [72] |

| Murine rPrP | To study how RNA can influence the aggregation of the murine rPrP | [73] |

| Pr from the brains of clinically sick mice that had been intracerebrally inoculated with the Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML) prion strain | To demonstrate that prions are not directly neurotoxic and that toxicity present in infected brain tissue can be distinguished from infectious prions | [74] |

| BV rPrP (amino acids 23–231) | To understand how different cofactors modulate prion strain generation and selection | [75] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms24054630

References

- Micoli, F.; Bagnoli, F.; Rappuoli, R.; Serruto, D. The role of vaccines in combatting antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 287–302.

- Shilova, O.; Shramova, E.; Proshkina, G.; Deyev, S. Natural and designed toxins for precise therapy: Modern approaches in experimental oncology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4975.

- Marzhoseyni, Z.; Shojaie, L.; Tabatabaei, S.A.; Movahedpour, A.; Safari, M.; Esmaeili, D.; Mahjoubin-Tehran, M.; Jalili, A.; Morshedi, K.; Khan, H.; et al. Streptococcal bacterial components in cancer therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 141–155.

- Khatuntseva, E.A.; Nifantiev, N.E. Cross reacting material (CRM197) as a carrier protein for carbohydrate conjugate vaccines targeted at bacterial and fungal pathogens. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 218, 775–798.

- Wulff, H.; Christophersen, P.; Colussi, P.; Chandy, K.G.; Yarov-Yarovoy, V. Antibodies and venom peptides: New modalities for ion channels. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 2019, 18, 339–357.

- Oliveira, L.V.; Wang, R.; Specht, C.A.; Levitz, S.M. Vaccines for human fungal diseases: Close but still a long way to go. Vaccines 2021, 6, 33.

- Geron, M. Production and purification of recombinant toxins. In Snake and Spider Toxins; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2068, pp. 73–84.

- Rodrigues, R.R.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Kremer, F.S.; Donassolo, R.A.; Júnior, C.M.; Alves, M.L.F.; Conceição, F.R. Recombinant vaccine design against Clostridium spp. toxins using immunoinformatics tools. In Vaccine Design; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2012, pp. 457–470.

- Pons, L.; Vilain, C.; Volteau, M.; Picaut, P. Safety and pharmacodynamics of a novel recombinant botulinum toxin E (rBoNT-E): Results of a phase 1 study in healthy male subjects compared with abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport®). J. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 407, 116516.

- Fredericks, L.R.; Lee, M.D.; Crabtree, A.M.; Boyer, J.M.; Kizer, E.A.; Taggart, N.T.; Roslund, C.R.; Hunter, S.S.; Kennedy, C.B.; Willmore, C.G.; et al. The species-specific acquisition and diversification of a K1-like family of killer toxins in budding yeasts of the Saccharomycotina. PLoS Genet. 2021, 17, e1009341.

- Giesselmann, E.; Becker, B.; Schmitt, M.J. Production of fluorescent and cytotoxic K28 killer toxin variants through high cell density fermentation of recombinant Pichia pastoris. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 228.

- Gier, S.; Schmitt, M.J.; Breinig, F. Expression of K1 toxin derivatives in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mimics treatment with exogenous toxin and provides a useful tool for elucidating K1 mechanisms of action and immunity. Toxins 2017, 9, 345.

- Carboni, G.; Fancello, F.; Zara, G.; Zara, S.; Ruiu, L.; Marova, I.; Pinnac, G.; Budroni, M.; Mannazzu, I. Production of a lyophilized ready-to-use yeast killer toxin with possible applications in the wine and food industries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 335, 108883.

- Chessa, R.; Landolfo, S.; Ciani, M.; Budroni, M.; Zara, S.; Ustun, M.; Cakar, Z.P.; Mannazzu, I. Biotechnological exploitation of Tetrapisisporaphaffii killer toxin: Heterologous production in Komagataellaphaffii (Pichia pastoris). Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 2931–2942.

- Salazar, M.H.; Clement, H.; Corrales-García, L.L.; Sánchez, J.; Cleghorn, J.; Zamudio, F.; Possani, L.D.; Acosta, H.; Corzo, G. Heterologous expression of four recombinant toxins from Panamanian scorpions of the genus Tityus and Centruroides for production of antivenom. Toxicon 2022, 13, 100090.

- Timofeev, S.; Mitina, G.; Rogozhin, E.; Dolgikh, V. Expression of spider toxin in entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicilliummuscarium and selection of the strain showing efficient secretion of the recombinant protein. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2019, 366, fnz181.

- Esipov, R.S.; Stepanenko, V.N.; Zvereva, I.O.; Makarov, D.A.; Kostromina, M.A.; Kostromina, T.I.; Muravyova, T.I.; Miroshnikov, A.I.; Grishin, E.V. Biotechnological method for production of recombinant peptide analgesic (purotoxin-1) from Geolycosa sp. spider poison. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2018, 44, 32–40.

- Shelukhina, I.V.; Zhmak, M.N.; Lobanov, A.V.; Ivanov, I.A.; Garifulina, A.I.; Kravchenko, I.N.; Rasskazova, E.A.; Salmova, M.A.; Tukhovskaya, E.A.; Rykov, V.A.; et al. Azemiopsin, a selective peptide antagonist of muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: Preclinical evaluation as a local muscle relaxant. Toxins 2018, 10, 34.

- Babenko, V.V.; Ziganshin, R.H.; Weise, C.; Dyachenko, I.; Shaykhutdinova, E.; Murashev, A.N.; Zhmak, M.; Starkov, V.; Hoang, A.N.; Tsetlin, V.; et al. Novel bradykinin-potentiating peptides and three-finger toxins from viper venom: Combined NGS venom gland transcriptomics and quantitative venom proteomics of the Azemiops feae viper. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 249.

- Romero-Giraldo, L.E.; Pulido, S.; Berrío, M.A.; Flórez, M.F.; Rey-Suárez, P.; Nuñez, V.; Pereañez, J.A. Heterologous expression and immunogenic potential of the most abundant phospholipase a2 from coral snake Micrurus dumerilii to develop antivenoms. Toxins 2022, 14, 825.

- Esipov, R.S.; Makarov, D.A.; Stepanenko, V.N.; Kostromina, M.A.; Muravyova, T.I.; Andreev, Y.A.; Dyachenko, I.A.; Kozlov, S.A.; Grishin, E.V. Pilot production of the recombinant peptide toxin of Heteractis crispa as a potential analgesic by intein-mediated technology. Protein Expr. Purif. 2018, 145, 71–76.

- Tereshin, M.N.; Komyakova, A.M.; Stepanenko, V.N.; Myagkikh, I.V.; Shoshina, N.S.; Korolkova, Y.V.; Leychenko, E.V.; Kozlov, S.A. Optimized method for the recombinant production of a sea anemone’s peptide. Mendeleev Commun. 2022, 32, 745–746.

- Fellermann, M.; Stemmer, M.; Noschka, R.; Wondany, F.; Fischer, S.; Michaelis, J.; Stenger, S.; Barth, H. Clostridium botulinum C3 toxin for selective delivery of cargo into dendritic cells and macrophages. Toxins 2022, 14, 711.

- Fellermann, M.; Huchler, C.; Fechter, L.; Kolb, T.; Wondany, F.; Mayer, D.; Michaelis, J.; Stenger, S.; Mellert, K.; Möller, P.; et al. Clostridial C3 toxins enter and intoxicate human dendritic cells. Toxins 2020, 12, 563.

- Eisele, J.; Schreiner, S.; Borho, J.; Fischer, S.; Heber, S.; Endres, S.; Fellermann, M.; Wohlgemuth, L.; Huber-Lang, M.; Fois, G.; et al. The pore- forming subunit C2IIa of the binary Clostridium botulinum C2 toxin reduces the chemotactic translocation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 810611.

- El-Chami, D.; Al Haddad, M.; Abi-Habib, R.; El-Sibai, M. Recombinant anthrax lethal toxin inhibits cell motility and invasion in breast cancer cells through the dysregulation of Rho GTPases. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 163.

- Rudenko, N.; Nagel, A.; Zamyatina, A.; Karatovskaya, A.; Salyamov, V.; Andreeva-Kovalevskaya, Z.; Siunov, A.; Kolesnikov, A.; Shepelyakovskaya, A.; Boziev, K.; et al. A monoclonal antibody against the C-terminal domain of Bacillus cereus hemolysin II inhibits HlyII cytolytic activity. Toxins 2020, 12, 806.

- Rudenko, N.; Siunov, A.; Zamyatina, A.; Melnik, B.; Nagel, A.; Karatovskaya, A.; Borisova, M.; Shepelyakovskaya, A.; Andreeva-Kovalevskaya, Z.; Kolesnikov, A.; et al. The C-terminal domain of Bacillus cereus hemolysin II oligomerizes by itself in the presence of cell membranes to form ion channels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 200, 416–427.

- Maksimov, I.V.; Blagova, D.K.; Veselova, S.V.; Sorokan, A.V.; Burkhanova, G.F.; Cherepanova, E.A.; Sarvarova, E.R.; Rumyantsev, S.D.; Alekseev, V.Y.; Khayrullin, R.M. Recombinant Bacillus subtilis 26DCryChS line with gene Btcry1Ia encoding Cry1Ia toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis promotes integrated wheat defense against pathogen Stagonospora nodorum Berk. and greenbug Schizaphis graminum Rond. Biol. Control 2020, 144, 104242.

- Zakharzhevskaya, N.B.; Tsvetkov, V.B.; Vanyushkina, A.A.; Varizhuk, A.M.; Rakitina, D.V.; Podgorsky, V.V.; Vishnyakov, I.E.; Kharlampieva, D.D.; Manuvera, V.A.; Lisitsyn, F.V.; et al. Interaction of bacteroides fragilis toxin with outer membrane vesicles reveals new mechanism of its secretion and delivery. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 2.

- Voltà-Durán, E.; Sánchez, J.M.; Parladé, E.; Serna, N.; Vazquez, E.; Unzueta, U.; Villaverde, A. The Diphtheria toxin translocation domain impairs receptor selectivity in cancer cell-targeted protein nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2644.

- Manoilov, K.Y.; Labyntsev, A.J.; Korotkevych, N.V.; Maksymovych, I.S.; Kolybo, D.V.; Komisarenko, S.V. Particular features of diphtheria toxin internalization by resistant and sensitive mammalian cells. Cytol. Genet. 2018, 52, 353–359.

- Chalenko, Y.; Sobyanin, K.; Sysolyatina, E.; Midiber, K.; Kalinin, E.; Lavrikova, A.; Mikhaleva, L.; Ermolaeva, S. Hepatoprotective Activity of InlB321/15, the HGFR Ligand of Bacterial Origin, in CCI4-Induced Acute Liver Injury Mice. Biomedicines 2019, 7, 29.

- Abramov, V.M.; Kosarev, I.V.; Motin, V.L.; Khlebnikov, V.S.; Vasilenko, R.N.; Sakulin, V.K.; Machulin, A.V.; Uversky, V.N.; Karlyshev, A.V. Binding of LcrV protein from Yersinia pestis to human T-cells induces apoptosis, which is completely blocked by specific antibodies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 122, 1062–1070.

- Ovchinnikov, S.V.; Bikmetov, D.; Livenskyi, A.; Serebryakova, M.; Wilcox, B.; Mangano, K.; Shiriaev, D.I.; Osterman, I.A.; Sergiev, P.V.; Borukhov, S.; et al. Mechanism of translation inhibition by type II GNAT toxin AtaT2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 8617–8625.

- Carboni, G.; Marova, I.; Zara, G.; Zara, S.; Budroni, M.; Mannazzu, I. Evaluation of recombinant Kpkt cytotoxicity on HaCaT cells: Further steps towards the biotechnological exploitation yeast killer toxins. Foods 2021, 10, 556.

- Gandomkari, M.S.; Ayat, H.; Ahadi, A.M. Recombinantly expressed MeICT, a new toxin from Mesobuthuseupeus scorpion, inhibits glioma cell proliferation and downregulates Annexin A2 and FOXM1 genes. Biotechnol. Lett. 2022, 44, 703–712.

- Kuzmenkov, A.I.; Nekrasova, O.V.; Peigneur, S.; Tabakmakher, V.M.; Gigolaev, A.M.; Fradkov, A.F.; Kudryashova, K.S.; Chugunov, A.O.; Efremov, A.G.; Tytgat, J.; et al. KV1. 2 channel-specific blocker from Mesobuthuseupeus scorpion venom: Structural basis of selectivity. Neuropharmacology 2018, 143, 228–238.

- Gigolaev, A.M.; Kuzmenkov, A.I.; Peigneur, S.; Tabakmakher, V.M.; Pinheiro-Junior, E.L.; Chugunov, A.O.; Efremov, R.G.; Tytgat, J.; Vassilevski, A.A. Tuning scorpion toxin selectivity: Switching from KV1.1 to KV1.3. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1010.

- Korolkova, Y.; Maleeva, E.; Mikov, A.; Lobas, A.; Solovyeva, E.; Gorshkov, M.; Andreev, Y.; Peigneur, S.; Tytgat, J.; Kornilov, F.; et al. New insectotoxin from Tibellus oblongus spider venom presents novel adaptation of ICK fold. Toxins 2021, 13, 29.

- Terpinskaya, T.I.; Osipov, A.V.; Kryukova, E.V.; Kudryavtsev, D.S.; Kopylova, N.V.; Yanchanka, T.L.; Palukoshka, A.F.; Gondarenko, E.A.; Zhmak, M.N.; Tsetlin, V.I.; et al. α -Conotoxins and α-Cobratoxin promote, while lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase inhibitors suppress the proliferation of glioma C6 cells. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 118.

- Makarova, Y.V.; Kryukova, E.V.; Shelukhina, I.V.; Lebedev, D.S.; Andreeva, T.V.; Ryazantsev, D.Y.; Balandin, S.V.; Ovchinnikova, T.V.; Tsetlin, V.I.; Utkin, Y.N. The first recombinant viper three-finger toxins: Inhibition of muscle and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 479, 127–130.

- Son, L.; Kryukova, E.; Ziganshin, R.; Andreeva, T.; Kudryavtsev, D.; Kasheverov, I.; Tsetlin, V.; Utkin, Y. Novel three-finger neurotoxins from Naja melanoleuca cobra venom interact with GABAA and nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Toxins 2021, 13, 164.

- Kvetkina, A.; Malyarenko, O.; Pavlenko, A.; Dyshlovoy, S.; von Amsberg, G.; Ermakova, S.; Leychenko, E. Sea anemone Heteractis crispa actinoporin demonstrates in vitro anticancer activities and prevents HT-29 colorectal cancer cell migration. Molecules 2020, 25, 5979.

- Godakova, S.A.; Noskov, A.N.; Vinogradova, I.D.; Ugriumova, G.A.; Solovyev, A.I.; Esmagambetov, I.B.; Tukhvatulin, A.I.; Logunov, D.Y.; Naroditsky, B.S.; Shcheblyakov, D.V.; et al. Camelid VHHs fused to human Fc fragments provide long term protection against botulinum neurotoxin a in mice. Toxins 2019, 11, 464.

- Rodrigues, R.R.; Ferreira, M.R.A.; Donassolo, R.A.; Alves, M.L.F.; Motta, J.F.; Moreira, C., Jr.; Salvarani, F.M.; Moreira, A.N.; Conceição, F.R. Evaluation of the expression and immunogenicity of four versions of recombinant Clostridium perfringens beta toxin designed by bioinformatics tools. Anaerobe 2021, 69, 102326.

- Ferreira, D.V.; dos Santos, F.D.; da Cunha, C.E.P.; Moreira, C., Jr.; Donassolo, R.A.; Magalhães, C.G.; Belo Reis, A.S.; Oliveira, C.M.C.; Barbosa, J.D.; Leite, F.P.L.; et al. Immunogenicity of Clostridium perfringens epsilon toxin recombinant bacterin in rabbit and ruminants. Vaccine 2018, 36, 7589–7592.

- Karpov, D.S.; Goncharenko, A.V.; Usachev, E.V.; Vasina, D.V.; Divisenko, E.V.; Chalenko, Y.M.; Pochtovyi, A.A.; Ovchinnikov, R.S.; Makarov, V.V.; Yudin, S.M.; et al. A Strategy for the Rapid Development of a Safe Vibrio cholerae Candidate Vaccine Strain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11657.

- Alomran, N.; Blundell, P.; Alsolaiss, J.; Crittenden, E.; Ainsworth, S.; Dawson, C.A.; Edge, R.J.; Hall, S.R.; Harrison, R.A.; Wilkinson, M.C.; et al. Exploring the utility of recombinant snake venom serine protease toxins as immunogens for generating experimental snakebite antivenoms. Toxins 2022, 14, 443.

- Alomran, N.; Chinnappan, R.; Alsolaiss, J.; Casewell, N.R.; Zourob, M. Exploring the utility of ssDNA aptamers directed against snake venom toxins as new therapeutics for snakebite envenoming. Toxins 2022, 14, 469.

- Neuschäfer-Rube, F.; Pathe-Neuschäfer-Rube, A.; Püschel, G.P. Discrimination of the activity of low-affinity wild-type and high-affinity mutant recombinant BoNT/B by a SIMA cell-based reporter release assay. Toxins 2022, 14, 65.

- Martin, T.; Möglich, A.; Felix, I.; Förtsch, C.; Rittlinger, A.; Palmer, A.; Denk, S.; Schneider, J.; Notbohm, L.; Vogel, M.; et al. Rho-inhibiting C2IN-C3 fusion toxin inhibits chemotactic recruitment of human monocytes ex vivo and in mice in vivo. Arch. Toxicol. 2018, 92, 323–336.

- Hashemi Yeganeh, H.; Heiat, M.; Kieliszek, M.; Alavian, S.M.; Rezaie, E. DT389-YP7, a recombinant immunotoxin against glypican-3 that inhibits hepatocellular cancer cells: An in vitro study. Toxins 2021, 13, 749.

- Cheung, L.S.; Fu, J.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Urbanowski, M.E.; Ihms, E.A.; Parveen, S.; Bullen, C.K.; Patrick, G.J.; Harrison, R.; et al. Second-generation IL-2 receptor-targeted diphtheria fusion toxin exhibits antitumor activity and synergy with anti–PD-1 in melanoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 3100–3105.

- Schmohl, J.U.; Todhunter, D.; Taras, E.; Bachanova, V.; Vallera, D.A. Development of a deimmunized bispecific immunotoxin dDT2219 against B-cell malignancies. Toxins 2018, 10, 32.

- Ryabchevskaya, E.M.; Evtushenko, A.; Granovskiy, D.L.; Ivanov, P.A.; Atabekov, J.G.; Kondakova, O.A.; Nikitin, N.A.; Karpova, O.V. Two approaches for the stabilization of Bacillus anthracis recombinant protective antigen. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 560–565.

- Ryabchevskaya, E.M.; Granovskiy, D.L.; Evtushenko, E.A.; Ivanov, P.A.; Kondakova, O.A.; Nikitin, N.A.; Karpova, O.V. Designing stable Bacillus anthracis antigens with a view to recombinant anthrax vaccine development. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 806.

- Evtushenko, E.A.; Kondakova, O.A.; Arkhipenko, M.V.; Kravchenko, T.B.; Bakhteeva, I.V.; Timofeev, V.S.; Nikitin, N.A.; Karpova, O.V. New formulation of a recombinant anthrax vaccine stabilised with structurally modified plant viruses. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1003969.

- Shulcheva, I.; Shchannikova, M.; Melnik, B.; Fursova, K.; Semushina, S.; Zamyatina, A.; Oleinikov, V.; Brovko, F. The zinc ions stabilize the three-dimensional structure and are required for the binding of staphylococcal enterotoxin-like protein P (SEIP) with MHC-II receptors. Protein Expr. Purif. 2022, 197, 106098.

- Gholami, N.; Cohan, R.A.; Razavi, A.; Bigdeli, R.; Dashbolaghi, A.; Asgary, V. Cytotoxic and apoptotic properties of a novel nano-toxin formulation based on biologically synthesized silver nanoparticle loaded with recombinant truncated Pseudomonas exotoxin A. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 3711–3720.

- Royal, J.M.; Reeves, M.A.; Matoba, N. Repeated oral administration of a KDEL-tagged recombinant cholera toxin B subunit effectively mitigates dss colitis despite a robust immunogenic response. Toxins 2019, 11, 678.

- Nekrasova, O.V.; Primak, A.L.; Ignatova, A.A.; Novoseletsky, V.N.; Geras’kina, O.V.; Kudryashova, K.S.; Yakimov, S.A.; Kirpichnikov, M.P.; Arseniev, A.S.; Feofanov, A.V. N-terminal tagging with GFP enhances selectivity of agitoxin 2 to Kv1.3-channel binding site. Toxins 2020, 12, 802.

- Calabria, P.A.; Shimokawa-Falcão, L.H.A.; Colombini, M.; Moura-da-Silva, A.M.; Barbaro, K.C.; Faquim-Mauro, E.L.; Magalhaes, G.S. Design and production of a recombinant hybrid toxin to raise protective antibodies against Loxosceles spider venom. Toxins 2019, 11, 108.

- Logashina, Y.A.; Lubova, K.I.; Maleeva, E.E.; Palikov, V.A.; Palikova, Y.A.; Dyachenko, I.A.; Andreev, Y.A. Analysis of structural determinants of peptide MS 9a-1 essential for potentiating of TRPA1 channel. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 465.

- Mannazzu, I.; Domizio, P.; Carboni, G.; Zara, S.; Zara, G.; Comitini, F.; Budroni, M.; Ciani, M. Yeast killer toxins: From ecological significance to application. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 603–617.

- Giovati, L.; Ciociola, T.; De Simone, T.; Conti, S.; Magliani, W. Wickerhamomyces yeast killer toxins’ medical applications. Toxins 2021, 13, 655.

- Leychenko, E.; Isaeva, M.; Tkacheva, E.; Zelepuga, E.; Kvetkina, A.; Guzev, K.; Monastyrnaya, M.; Kozlovskaya, E. Multigene family of pore-forming toxins from sea anemone Heteractis crispa. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 183.

- Ma, J.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R. Recombinant mammalian prions: The “correctly” misfolded prion protein conformers. Viruses 2022, 14, 1940.

- Imamura, M.; Tabeta, N.; Iwamaru, Y.; Takatsuki, H.; Mori, T.; Atarashi, R. Spontaneous generation of distinct prion variants with recombinant prion protein from a baculovirus-insect cell expression system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 613, 67–72.

- Abskharon, R.; Wang, F.; Wohlkonig, A.; Ruan, J.; Soror, S.; Giachin, G.; Pardon, E.; Zou, W.; Legname, G.; Ma, J.; et al. Structural evidence for the critical role of the prion protein hydrophobic region in forming an infectious prion. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1008139.

- Abdelaziz, D.H.; Thapa, S.; Brandon, J.; Maybee, J.; Vankuppeveld, L.; McCorkell, R.; Schätzl, H.M. Recombinant prion protein vaccination of transgenic elk PrP mice and reindeer overcomes self-tolerance and protects mice against chronic wasting disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 19812–19822.

- Hwang, S.; Tatum, T.; Lebepe-Mazur, S.; Nicholson, E.M. Preparation of lyophilized recombinant prion protein for TSE diagnosis by RT-QuIC. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 895.

- Kovachev, P.S.; Gomes, M.P.; Cordeiro, Y.; Ferreira, N.C.; Valadão, L.P.F.; Ascari, L.M.; Rangel, L.P.; Silva, J.L.; Sanyal, S. RNA modulates aggregation of the recombinant mammalian prion protein by direct interaction. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12406.

- Benilova, I.; Reilly, M.; Terry, C.; Wenborn, A.; Schmidt, C.; Marinho, A.T.; Risse, E.; Al-Doujaily, H.; WigginsDeOliveira, M.; Sandberg, M.K.; et al. Highly infectious prions are not directly neurotoxic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 23815.

- Fernández-Borges, N.; Di Bari, M.A.; Eraña, H.; Sánchez-Martín, M.; Pirisinu, L.; Parra, B.; Elezgarai, S.R.; Vanni, I.; López-Moreno, R.; Vaccari, G.; et al. Cofactors influence the biological properties of infectious recombinant prions. Acta. Neuropathol. 2018, 135, 179–199.

- Jack, K.; Jackson, G.S.; Bieschke, J. Essential components of synthetic infectious prion formation de novo. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1694.