Influenza infection is serious and debilitating for humans and animals. The influenza virus undergoes incessant mutation, segment recombination, and genome reassortment. Antiviral therapy has been used for the treatment of influenza since the development of amantadine in the 1960s; however, its use is hampered by the emergence of novel strains and the development of drug resistance. Thus, combinational therapy with two or more antivirals or immunomodulators with different modes of action is the optimal strategy for the effective treatment of influenza infection.

1. Introduction

“Flu” is the colloquial term used to describe an emerging disease whose major causative agent is influenza virus A or B. It is a contagious infection that spreads from one person to another through patient sneezes or coughs. Influenza symptoms include a runny nose, dry cough, sore throat, high fever, chills, headaches, and body aches [

1]. In most cases, patients improve within a few days; however, when complications develop, flu can also cause morbidity and mortality, resulting in epidemics.

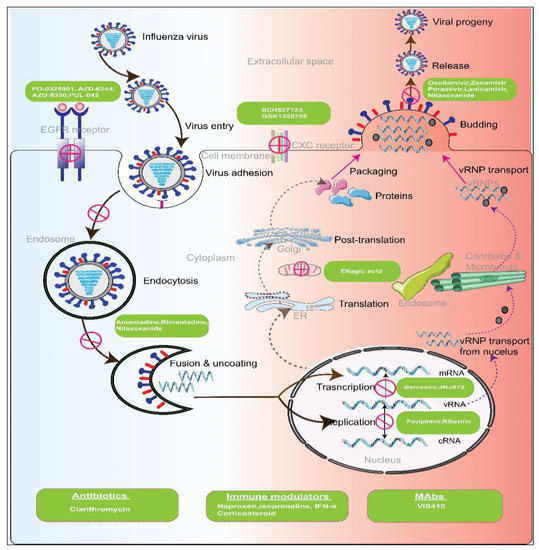

Mode of Action of Influenza Virus Replication: Such as all viruses, influenza viruses require invading a host cell to replicate, release, and subsequently spread. This process involves several stages.

Attachment and Entry: The influenza virus enters the host through the attachment of its hemagglutinin (HA), a type of glycoprotein present in the viral envelope, to sialic acid residues on the glycoprotein or glycolipid receptors of the host. The cell then endocytoses the virus, after which the HA protein undergoes a change in shape and unites with the endosomal membrane within the acidic environment of the endosome [

2]. Viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) complexes are then released into the host cytoplasm and travel to the nucleus of the host cell, where they replicate and generate viral mRNA transcripts. This viral entry step can be an attractive target for viral inhibition strategies that block the ion channel and disable the release of vRNP into the cytoplasm [

3].

RNA and Protein Production: Viral vRNP complexes carry out primary transcription in the host’s nucleus, producing the proteins needed for replication. The mechanism of primary transcription is called “cap snatching,” in which the 5′ methylguanosine cap of the mRNA of the host is bound by polymerase protein 2 (PB2), followed by removal of the cap and 10–13 nucleotides by the viral endonuclease, PA. The resulting oligonucleotide is used by a viral polymerase protein 1 (PB1) as a primer for transcription. This stage of viral processing is also a potential target for antiviral therapy. By inhibiting the cap-snatching process, the transcription of viral mRNA can be blocked, thereby inhibiting the production of the proteins necessary for virion formation [

4]. The ten primary proteins produced by the translation of the eight segments of the genome in influenza A and B include one of the components of the vRNP complex, two matrix proteins (M1 and M2), two NS proteins (NS1 and NEP), neuraminidase (NA), PB1, PB2, nucleoprotein (NP), and HA. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase can be selectively inhibited by antiviral agents, making this another possible target for viral inhibition [

5].

Assembly and Release: Following the creation of the initial proteins, the eight negative-sense viral RNA (vRNA) segments in influenza A and B are used to create eight positive-sense complementary RNA (cRNA) strands. These strands are missing the 5′ capped primer and the 3′ poly (A) tail found in mRNA. A negative sense of vRNA is created from this cRNA. Various viral proteins generated subsequently assemble and assist this vRNA in exiting the nucleus and entering the cytoplasm of the host cell [

6].

During this period, HA and NA are glycosylated, polymerized, and acylated in the cytoplasm and, together with M2, are directed to the plasma membrane, where they become anchored. The proteins then interact with the other matrix protein, M1, and start the budding process. The virus buds after at least eight RNA segments arrive at the location via a yet unknown mechanism. Finally, NA cleaves the sialic acid of the HA protein of the progenitor, allowing the virus to exit the cell. This NA-mediated step is an attractive inhibitory target as preventing the breakdown of sialic acid residues would reduce viral infectivity by restricting progeny virus dispersal inside mucosal secretions [

7].

2. Classes of Approved Antivirals for Influenza

So far, four classes of antivirals, including adamantanes, neuraminidase inhibitors, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors, and polymerase acidic endonuclease inhibitors, are considered the approved class of antivirals to treat influenza patients.

2.1. Adamantanes—M2 Ion Channel Blockers

Adamantanes, also known as M2 ion channel blockers, limit the early stages of virus replication by blocking the ion channel formed from the M2 protein encoded by the M gene of the influenza A virus [

8]. If treatment is initiated within 48 h of infection, it has the potential to shorten the illness by 1.5 days [

9]. Because of their low cost and ready availability, adamantanes have been used for almost 50 years to treat infections caused by the influenza A virus [

10].

2.2. Neuraminidase Inhibitors

Until 2018, neuraminidase inhibitors (NAIs) represented the only FDA-approved class of antivirals. The BM2 protein in influenza B viruses is such as the M2 protein in influenza A viruses; however, it is not susceptible to M2 blockers. Moreover, most circulating human influenza viruses are resistant to M2 blockers; therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) does not recommend their use. Despite these caveats, NAIs are approved for use against both influenza A and B infections and do stop viruses from spreading and infecting healthy cells [

11].

.3. RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Inhibitor

This class of antivirals, which consists of the single drug favipiravir, inhibits viral RNA synthesis. Though still not approved by the FDA, it was approved in Japan in 2014 for the treatment of novel and re-emerging influenza virus infections and in China in 2016. Favipiravir is more effective than oseltamivir in treating influenza infections [

24,

25]. A notable attribute of favipiravir is the apparent lack of development of favipiravir-resistant viruses, a testament to the quality of favipiravir as an antiviral drug.

As a chain terminator, favipiravir prevents viral RNA production. This contrasts with drugs that inhibit genomic RNA synthesis, which leads to the production of drug-resistant mutations by viral RdRp, a component of the low-fidelity RdRp-viral RNA complex. This is the most important feature that distinguishes favipiravir from prior anti-influenza drugs [

26]. Other anti-influenza medications, such as NAIs and baloxavir (see below), prevent the transmission of infection but facilitate the production of genomic RNA, which can drive the creation of drug-resistant viruses.

2.4. Polymerase Acidic Endonuclease Inhibitor

This is a new class of antivirals consisting of the single drug baloxavir marboxil (trade name, Xofluza), which was first approved in Japan in 2018, and later the same year by the FDA for treating uncomplicated flu. A single oral dose of baloxavir marboxil is required to treat influenza.

Baloxavir marboxil is a specific inhibitor of the cap-dependent endonuclease of the viral RdRp complex. In the presence of baloxavir, the integrated RdRp-viral RNA complex synthesizes cRNA without the cap structure, which limits mRNA synthesis and causes failure of subsequent viral protein synthesis.

3. Challenges of Influenza Therapy

The major challenge in treating influenza is the antiviral resistance of most human influenza A virus strains toward M2 inhibitors. Adamantanes work only against influenza A viruses and are not effective against influenza B viruses. An adamantane-resistant influenza A virus was identified during a 1980 outbreak [29], but until 2000 only 1–2% of seasonal influenza A subtypes showed resistance to both amantadine and rimantadine [30,31]. This percentage has increased substantially since then [32], such that, by 2013, approximately 45% of all extant influenza A virus subtypes worldwide showed resistance to adamantanes [33].

Another shortcoming in treating influenza virus infections is the requirement for in vivo disease models for influenza-related research, which can be challenging and problematic from the standpoint of evaluating antiviral treatment and efficacy. Numerous animal models often require repeated analysis of host-virus interactions, transmission methods, and host immunological reactions to various influenza viruses. Antivirals that target influenza can be evaluated using a variety of animal models, but each has its advantages and disadvantages. Mice are the most popular model for in vivo investigations, especially for preclinical evaluations of influenza antivirals. That said, ferrets are best suited as an animal model for studying novel antiviral drugs because these animals can contract a variety of human, avian, and swine influenza strains and recapitulate many clinical symptoms observed in humans after viral infections [35].

4. Limitations of Antivirals and Anti-Influenza Drug-Resistance Mechanisms

4.1. Adamantanes

Adamantanes were the first approved antiviral class for the treatment of influenza. Although they are effective against influenza A (but not influenza B), they are not currently recommended for the treatment of influenza A owing to increased levels of resistance [

43]. M2 inhibitor-resistant strains can spread from person to person, are pathogenic, and can occasionally be recovered from untreated individuals. Human isolates of very virulent A/H5N1 influenza viruses are naturally resistant to these antivirals [

44].

Approximately 95% of adamantane-resistant influenza A virus subtypes have been discovered to harbor an S31N mutation [

33,

45]. This mutation causes adamantane resistance in 98.2% of H3N2 isolates, with the remainder (1.8%) attributable to L26F, V27A, and A30T mutations [

32]. The swine-origin influenza A H1N1 subtype that triggered the pandemic of 2009 also had an S31N mutation in M2 that made it resistant to amantadine and rimantadine [

46]. Similarly, the avian influenza A virus subtypes H5N1 and H7N9, which originated in 2003 and 2013, respectively, and caused serious zoonotic infections in humans, both have the S31N mutation in M2 and are therefore adamantane resistant [

47].

4.2. NAIs

As is the case with M2, multiple amino acids in or surrounding the active site of NA in the influenza A virus have changed during the development of resistance to NAIs [

48], including E119V, R292K, I222V, H274Y, and N294S. Most of these mutations directly or indirectly change the shape of the active site of NA, drastically reducing NAI binding [

49,

50,

51].

Although resistance to M2 inhibitors became more prevalent in influenza A virus H3N2 subtypes, resistance to NAIs initially emerged and became predominant in the H1N1 subtype [

45]. Oseltamivir, an antiviral that comes in capsule or powdered form for the preparation of liquid suspensions, has a high oral bioavailability. Zanamivir, on the other hand, is a less suitable NAI because it can only be given through inhalation [

17]. Because of oseltamivir’s widespread use since 2000, influenza variants harboring NA mutations H274Y, N294S, Y252H, I223R/V, and some others have developed resistance to the drug [

52,

53,

54,

55].

4.3. Favipiravir

Only people treated with favipiravir can develop acquired resistance to the drug [

59]. However, an investigation showed that an early isolate from the 2009 H1N1 pandemic known as influenza A/England/195/2009 (Eng195) might exhibit favipiravir resistance [

65]. This study reported that two mutations, K229R in the motif F of PB1 and P653L in PA, were required for the evolution of resistance to favipiravir. K229R conferred resistance to favipiravir at the expense of polymerase activity, an effect that was balanced by the P653L mutation [

65].

Although the use of favipiravir is unlikely to be common enough in the community to support selection for resistance, pre-existing drug-resistant mutations have spread in the absence of widespread drug use [

66]. Favipiravir resistance could grow across the community through drift or through combination with other beneficial mutations if there is no cost to resistance.

Favipiravir is currently recommended only in China and Japan. Apart from emerging resistance, favipiravir’s poor solubility in aqueous media is another limitation that may reduce its effectiveness

in vitro [

67]. Furthermore, favipiravir was found to raise the risk of embryotoxicity and teratogenicity, indicating the need for strict regulation of its production and medical application. Additionally, although favipiravir does not possess the typical properties of nucleoside analogs that might cause mitochondrial toxicity, harmful effects on mitochondria cannot be fully ruled out [

68,

69].

4.4. Baloxavir Marboxil

Influenza A viruses have been shown to develop resistance to baloxavir through mutations at isoleucine 38 (I38X), a highly conserved residue in the PA catalytic site. According to a study by Omoto and colleagues, mutations in the influenza virus’s PA protein reduce the susceptibility to baloxavir [

70]. Specifically, influenza strains carrying E23/G/K, E36V, E37T, I38T/F/M/L, E119D, or E119G mutations in PA are significantly more resistant to baloxavir in vitro [

71,

72,

73]. Among these, PA I38T is a major mutation that reduces baloxavir susceptibility and alters its EC

50 values for influenza A by 30- to 50-fold and for influenza B by 7-fold [

70].

5. Drug Combination Therapy: As an Alternative Treatment Option for the Influenza Infection

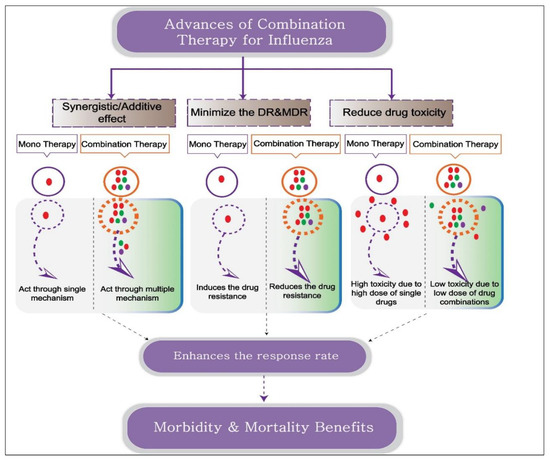

Combination drug therapy is a therapeutic strategy in which a disease is treated with two or more drugs. To promote drug synergism, researchers can design combination therapy to target multiple pathways of the host and pathogen, thereby resulting in benefits greater than simple additive effects (Figure 1). In addition to enhancing therapeutic efficacy, this can enable drugs to be used at lower, individualized dosages, thereby increasing patient tolerance and reducing drug toxicity. The likelihood of resistance to two antivirals is decreased compared with that to a single antiviral, so combination therapy serves to increase the antiviral spectrum. The main goal of combination therapy, which is typically given to critically ill patients when the first-line therapy fails, is to eliminate the infection and restore normal functioning (Figure 1). This is already the gold standard approach for treating several viral infections, including HIV-1 and HCV.

Figure 1. Schematic representation depicting the advantages of combination therapy over monotherapy. Combination therapy includes two or more drugs or immunomodulators with the same or different therapeutic targets. Antiviral combination with different therapeutic activities promotes synergistic action, reducing drug toxicity and drug resistance proportion. The combination of an antiviral and an immune modulator targets virus and host factors, thereby inhibiting virus replication and simultaneously enhancing the host defense mechanism and conferring morbidity and mortality benefits.

5.1. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting Same Viral Protein

Combination therapy with two different drugs belonging to the same class is possible if the drugs possess completely different binding interactions with the viral protein. The oseltamivir + zanamivir and oseltamivir + peramivir combinations belong to this category.

Oseltamivir + zanamivir: Oseltamivir and zanamivir are both members of the NAI class, but they bind to different NA active sites. In a mixed infection model, oseltamivir-zanamivir combination therapy suppressed oseltamivir and zanamivir-resistant viruses very effectively [

83]. This approach might assist in maintaining the clinical value of NAIs by preventing the growth of drug-resistant strains.

Oseltamivir + peramivir: Oseltamivir plus peramivir is another combination whose individual components target the same viral mechanism. Although both compounds act as neuraminidase inhibitors, peramivir binds more strongly to the enzyme than oseltamivir and thus confers protection against the influenza A virus. Twice daily administration of these drugs in influenza-infected mice was shown to significantly increase survival rate compared with a single therapy, demonstrating that combination therapy with these two drugs has an advantage in treating influenza compared with a suboptimal dose of the single drug [

84] (

Figure 2).

Figure 2. Potential targets of antiviral and other immunomodulators for different factors of pathogen and host. Influenza virus enters the cytoplasm by receptor-mediated endocytosis by recognition of sialic acid receptors. The low pH in the endosome induces the release of RNA, a therapeutic target of several antivirals. Transcription and replication from RNA occur in the nucleus, and both steps are inhibited by antivirals targeting the PA endonuclease and RdRps. Packaging and release of the virion occur at the cell membrane, and neuraminidase inhibitors block this step. Immunomodulators and other agents target host factors and stimulate the immune system against viral infection.

5.2. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting Two or More Viral Proteins

Drugs in combination therapy target two or different pathways of the influenza virus is an effective treatment strategy. It improves therapeutic efficacy by providing synergistic activity, lower drug dose utility, and better treatment response rate.

5.2.1. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting Cap-Dependent Endonuclease & RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase

Antiviral combination therapy targeting cap-dependent endonuclease & RNA-dependent RNA polymerase has shown its advantage over both drugs used alone.

Baloxavir + favipiravir: A recent

in vitro investigation of combination therapy reported synergistic effects of baloxavir-favipiravir combination therapy [

85]. However, considerable additional investigation will be required to confirm the effectiveness of combination therapy with these two polymerase inhibitors against resistant influenza strains.

5.2.2. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting Cap-Dependent Endonuclease & Neuraminidase

The synergistic effects of antivirals targeting the cap-dependent endonuclease & neuraminidase of the influenza virus have been reported in several studies.

Baloxavir + oseltamivir: Although findings from a recent study suggest that baloxavir and NAI combination therapy is not generally advisable for treating acute influenza patients in a clinical setting [

86], some studies have reported synergistic effects of baloxavir-oseltamivir combination therapy in mice [

87,

88]. Compared with monotherapy, a suboptimal dose of the antiviral drug baloxavir marboxil together with oseltamivir phosphate showed improved efficacy in terms of virus-induced mortality, cytokine/chemokine production, and morphological changes in the lungs [

88].

5.2.3. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase & Neuraminidase

Another class of antivirals targeting the RdRp, and neuraminidase of influenza virus have demonstrated their therapeutic utility in several in vitro, in vivo, and clinical studies.

Favipiravir + oseltamivir: In a mouse model, this combination offered

in vivo synergy, providing 60–80% protection together with improved body weight maintenance during A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) influenza virus infection [

89]. A recent study performed a similar comparative analysis in humans to assess the efficacy of oseltamivir plus favipiravir combination therapy and oseltamivir monotherapy [

90]. Although the sample size used for evaluating favipiravir-oseltamivir combination therapy was small compared with that of oseltamivir monotherapy, combination therapy was nevertheless demonstrated to hasten patient recovery from influenza infection [

90]. These results indicate that, in individuals with chronic influenza, combining favipiravir and oseltamivir may improve clinical outcomes and increase therapeutic efficacy.

5.2.4. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting the M2 Ion Channel & Neuraminidase

Various influenza mutations resulting from the widespread use of M2 ion channel blockers, together with adjunctive antivirals such as neuraminidase inhibitors, have provided superior protection against influenza infection as combination therapy.

Peramivir + rimantadine: Combined administration of the neuraminidase inhibitor, peramivir, and M2 ion channel blocker, rimantadine, for five consecutive days was shown to cause significant and synergistic weight loss in mice infected with influenza A virus [

96]. These antivirals target two distinct viral proteins—an advantage compared with targeting a single protein.

Oseltamivir + rimantadine: An evaluation of prophylactic and therapeutic benefits of the drug combination, oseltamivir plus rimantadine, investigated two different dose patterns in a mouse model. This combination showed a protective index of ~79% in a prophylactic setting and ~80% during a therapeutic course [

93] and effectively reduced viral titer, pneumonia parameters, and individual drug dosage requirements.

5.2.5. Antiviral Combination Therapy Targeting the M2 Ion Channel, Neuraminidase & RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase

In addition to the dual target antiviral combinations listed above, antiviral combination therapy with more than two viral targets, such as the M2 ion channels, neuraminidase & RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, is more advantageous against drug-resistant strains of influenza.

Oseltamivir + amantadine + ribavirin: Triple-combination antiviral drug treatment (TCAD) with amantadine, oseltamivir, and ribavirin has shown synergistic activity

in vitro against both drug-sensitive and drug-resistant strains of influenza A [

96,

97]. Compared with dual combination therapy, TCAD exerts a greater inhibitory effect and is also more effective in reducing the occurrence of resistance during

in vitro passage [

98]. In an

in vivo model, TCAD therapy was reported to be highly effective in reducing mortality and weight loss in mice infected with the influenza A virus. It was also shown to provide survival support in cases where treatment is delayed (up to 72 h) after viral infection [

99].

5.3. Combination Therapy Targeting Host and Pathogen Molecular Mechanisms

In addition to direct antiviral combinations, other host-targeted therapeutics, such as monoclonal antibodies, immunomodulators, cell signaling inhibitors, anti-inflammatory agents, and antioxidant agents, can be co-administered together with direct antiviral agents as part of a combination therapy approach for treating drug resistance, immunocompromised patients, and patients with severe influenza. Such approaches offer superior advantages compared with single-drug treatment.

Because a neuraminidase inhibitor (e.g., oseltamivir) alone is less effective in treating patients with severe influenza, adjunctive therapy with the antibiotic, clarithromycin, and anti-inflammatory drug, naproxen, in a combination regimen provides effective protection, reducing mortality, hospital stay, and defervescence in adult influenza patients. This combination therapy mounted a more rapid antiviral defense and produced a more rapid decline in viral load in hospitalized pediatric influenza patients [

102,

103]. The Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathway plays a central role in the replication of the influenza virus. Hence, MEK inhibitors such as PD-0325901, AZD-6244, AZD-8330, and RDEA-119, together with oseltamivir, show increased antiviral activity

in vitro, laying the groundwork for the development of an alternative therapeutic regimen against influenza through further

in vivo and clinical studies [

104]. The neutrophil chemokine receptor, CXCR2 (CXC chemokine receptor 2), is the main determinant of neutrophil infiltration and a therapeutic target for reducing inflammation. The combination of oseltamivir and the CXCR2 antagonist, SCH527123, was shown to markedly enhance survival in mice and attenuate the severity of lung pathology in infected animals [

105].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms11010183