Food production is a driver of the devastation of natural capital, including massive biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and more [

5,

6]. There is, however, hope for fixing food systems, since in some regions of the world healthy and sustainable food habits can still be found [

7], as is the case of the Mediterranean Diet (MD), which is a cultural asset recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as an intangible heritage of the humankind [

8]. Yet, MD is best known for its food pattern, which is well-known for being simultaneously healthy and sustainable [

1,

9,

10]. High adherence scores to the MD can significantly enhance the nutrition quality and public health of populations [

10,

32,

33,

34,

35] while being respectful of the environment [

36,

37,

38] and, in certain cases, contributing to the preservation of agro-biodiversity [

39,

40]. A change in the food system paradigm has been proposed by many, mostly consisting in promoting the adoption of more sustainable diets, with many similarities to the MD (e.g., planetary diet by the EAT-Lancet commission).

Phenolic Compounds

Mediterranean aromatic plants are generally rich in phenolic compounds (also known as phenols or phenolics), which are a heterogeneous group of plant secondary metabolites, having in common the presence of at least one aromatic ring and hydroxyl group (OH), which is the root for their name, as phenol is the simplest compound with such features. The designation “phenolic compounds” is broad enough to include from simple molecules to polymers, diverging not only in size but also in chemical properties (as polarity) due to differences in functional groups (such as ester and acid). Given the heterogeneity of this group of compounds, they have been named and categorized differently by different authors according to several viewpoints [

55].They can be found in variable amounts in plant foods and are involved in colour (e.g., pigments), flavour (e.g., responsible for astringency, bitterness), and food safety (due to antimicrobial activity). Phenolic compounds from foods are most often valued for their general antioxidant character and they have been recently categorized as phytonutrients because of the mounting evidence and growing awareness of their health-promoting features [

47,

48,

49]. Phenolic compounds exist in fresh vegetables (e.g., leafy vegetables, aromatic herbs, nuts) and processed (fruit juice, tea, coffee, wine) and, although their release kinetics during food digestion and bioavailability afterwards are still unclear, they seem to depend on the food matrix, on the interactions with other nutrients and more [

50,

51,

52].

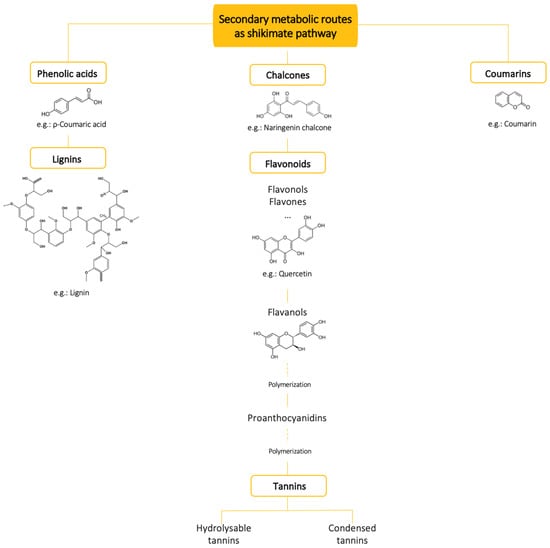

Figure 2 summarises the main groups of plant phenolic compounds also found in Mediterranean aromatic herbs. Some examples are included and more information (e.g., culinary uses, bioactivities) can be found in Table 1.

Figure 2. Main groups of phenolic compounds in Mediterranean aromatic plants.

When categorizing phenolics regarding plant metabolic pathways, three large groups can be first considered: phenolic acids, chalcones, and coumarins (

Figure 2) because they can be precursors of others [

55]. Phenolic acids can be precursors in the synthesis of lignins. In another pathway, chalcones may originate flavonoids, which, in turn, may condensate. Polymerization proceeds; proanthocyanidins are first oligomers and then polymers composed of units of flavanols. These polymers may ultimately originate tannins, of high molecular mass. Based on different properties, two subclasses can be considered, hydrolysable and condensed tannins [

56]. Coumarins, the third large group above-referred, do not undergo any further transformation [

57].

When considering overall function, structure, and occurrence, some types of compounds stand out, as is the case of flavonoids.

As roughly overviewed in

Figure 2, flavonoids can be subdivided into flavonols, dihydroflavonols, isoflavones, and flavanols, according to the degree of hydrogenation and hydroxylation of their three-ring structure [

56,

58]. Flavonoids bind easily to sugars resulting in a pigment whose colour grade depends on the nature of the chemical bond established between the phenol moiety and the sugar residue [

57].

Flavanols, also referred to as flavan-3-ols or catechins (

Figure 2), are derivatives of flavans and include catechin, epicatechin gallate, epigallocatechin, epigallocatechin gallate, proanthocyanidins, and thearubigins [

59]. According to the same authors, catechin is water soluble and can chelate heavy metals and bind to proteins, including bacterial toxins of proteinaceous nature, which may explain its antimicrobial and detoxifying properties. Catechin is mostly found in green tea but is also present in rosemary. Catechin and epigallocatechin may polymerize together in different proportions, and the levels of antioxidant activity seem to depend on the degree of polymerization (

Figure 2). Condensed tannins are obtained after a series of condensation and polymerization reactions [

57,

63].

Condensed tannins are thus flavanol polymers not readily hydrolysed that are responsible for the astringency taste of many plant foods [

57]. As polyphenols in general, they were regarded by nutritionists as antinutrients, to be avoided. However, state-of-the-art knowledge, especially about the human microbiome, has been disclosing their relevance as phytonutrients [

64]. According to Selma et al. [

65], dietary polyphenols act as phytonutrients by first interacting with the gut microbiota and often being transformed by bacteria before entering the bloodstream. Still, according to the same researchers, some health benefits from phenolic compounds may result, to a large extent, from such microbial bioactive metabolites.

Role of Aromatic Plants in the MD Cuisine

Culinary traditions between Mediterranean countries changed significantly over the past decades, but the habit of enriching food with flavours and aromas remains across the Mediterranean countries [41,43]. Aromatic herbs are essential ingredients of MD, used as food additives and condiments, and as herbal teas [44]. Aromatic herbs can be a pleasant and healthier substitute for salt (NaCl) in cooking. Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.), thyme (Thymus vulgarisL.), sage (Salvia officinalis L.), and rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) are well-known aromatic herbs, which belong to the Lamiaceae family. On the other hand, the mints (a large number of species and subspecies) are widely used as medicinal aids (in folk medicine) because of their reported health-promoting actions on top of their aromas. Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.), Peppermint (Mentha piperita L.) and kitchen mint (Mentha spicata L.) are examples of species with subspecies found only in specific habitats. Aromatic herbs used in Mediterranean cuisine are rich in bioactive compounds and, thus, contribute to the MD’s health benefits. Some documented health outcomes of spices and herbs used in Mediterranean cuisine are highlighted in Table 1, which is focused on the native plants of the region.

Table 1. Prominent phenolic compounds, health-promoting actions and other properties of aromatic herbs commonly used in Mediterranean cuisine.

[please insert table 1 here]

As can be observed in Table 1, the ability to neutralize free radicals and the antimicrobial character are common features of phenolic compounds, which can easily be proven in vitro. Studies on the mechanism of action of certain phenolics are also referenced but the number of published clinical studies is reduced. Beneficial health outcomes are rarely attributed to a single compound but rather to whole foods and notably to the Mediterranean dietary pattern (MD), in which aromatic herbs play a key role.

Wild Mediterranean Aromatic Plants and Conservation Concerns

Many Mediterranean herbs are narrowly distributed, or local endemics and their scent and flavour are potentiated by Mediterranean climatic conditions. Due to the presence of bioactive compounds, Mediterranean herbs provide not only an agreeable aroma and taste to food, but also improve food preservation while providing multiple health benefits [

78]. It should be noted that plants, notably wild herbs, may contain health-promoting and/or poisoning compounds. Seldom, the same compound can be beneficial or deleterious depending on the dosage. The Mediterranean culinary herbs herein described have been used for centuries mainly as seasonings and may therefore be considered as GRAS (generally recognised as safe). Many locals have the necessary empirical knowledge to select the desired species in the wild including for use in folk medicine.

Many aromatic herbs are locally harvested to be used as basic ingredients in several dishes. However, some Mediterranean Lamiaceae herbs with potential relevance for the Mediterranean Diet are listed in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as “near threatened”, “vulnerable”, “endangered”, or “critically endangered” (Table 2).

Table 2. Examples of Mediterranean aromatic species listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature, IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

[pls insert table 2 herein]

The causes contributing to decline or extinction of plant species are mainly uncontrolled overcollection, urban and tourism pressure, and climate change.

The Mediterranean basin (still a hotspot of biodiversity) harbours many endemic species including aromatic herbs, such as

Origanum dictamnus L. (known as dittany) endemic of Crete Island,

Thymus lotocephalus G. López & R. Morales, found in Algarve, Portugal, or the

Capsicum annuum cv holding the protected designation of origin (PDO) “pemento de Herbón”, commonly known as pimiento de Padrón, only found in a certain region of Galicia, Spain [

46]. As noted before [

2,

3] and according to most probable scenarios from climate change models, the Mediterranean basin is one of the regions across the globe that will be expected to be strongly affected [

89], negatively impacting crop quality and productivity. Environmental changes are of particular interest for the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites like phenolic compounds, namely in Mediterranean aromatic plants [

90,

91], consequently changing their corresponding health benefits.

Concluding Remarks and Prospects

The Mediterranean food culture, which is deeply connected to the territories, is likely to be directly and indirectly affected by the changing environmental conditions in the area, since in the Mediterranean basin, observations from the past decades and most probable scenarios from climatic models prescribe a drift towards a semi-arid climate. Anthropogenic pressure and extreme weather events are challenging the resilience of Mediterranean plants and driving many of them to extinction. Of particular concern is the increasing demand for wild aromatic species and their overharvesting together with climate change acceleration threatens the survival of wild populations of some aromatic species with a great role in the Mediterranean Diet. In practice, stimulating higher adherence levels to the MD includes raising awareness on the complex aromas and health benefits conveyed by phenolic compounds from local aromatic herbs, along with the associated environmental constraints, in the “one health” viewpoint (please see Section 6 and Section 7).

Possible strategies for sustainable exploitation of Mediterranean plants may include the commercial valuation of local cultivars, which will benefit small local businesses. Tools to implement such strategy include promoting geographical indication seals, responsible marketing, and consumer literacy on healthy sustainable food habits as well as on nature’s preservation. Wild biodiversity and agro-biodiversity are as connected as are human and planetary health. Awareness-raising actions and citizen science about endemism and other natural constraints may trigger bottom-up pressure towards species conservation and more sustainable agricultural practices. In addition, awareness-raising and other local actions about the seasonal character of many foods and their health-related value will certainly highlight the linkage of food habits with cultural landscapes, a cornerstone of the MD, thus enabling the sustainable exploitation of Mediterranean plants.