Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Allergy

Members of the virome may collaborate with the human host to retain mutualistic functions in preserving human health. Although a person’s virome can alter over time, viral presence in a person can be extremely stable. Since viruses are present in the environment all the time, it is easy to imagine where the members of the changeable virome originate.

- virus

- glomerulonephritis

- virome

- hepatitis

1. The Human Virome and Its Body Habitats

Members of the virome may collaborate with the human host to retain mutualistic functions in preserving human health. Evolutionary theories contend that a particular microbe’s ubiquitous existence may signify a successful partnership with the host. The higher risk of cervical cancer in women infected with high-risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV) strains is an example of how some persistent DNA viral infections are clearly related with disease. This may be comparable to the bacterial infections that persist in the microbiome and have the potential to cause disease but are not always manifest [9].

Although a person’s virome can alter over time, viral presence in a person can be extremely stable. Since viruses are present in the environment all the time, it is easy to imagine where the members of the changeable virome originate. However, recognized host defenses and underappreciated processes are probably the main components of the systems that support viral–host cohabitation. Viruses produce proteins that control the cell cycle [10], host gene expression, and host immunological responses [11,12,13,14]. Micro RNAs that control cellular functions are also encoded by viruses [15]. Consequently, viruses that are latent and persistently infected are constantly engaging with the host in a variety of ways. The intricate impacts of interactions between the virus and host during infection are being studied by many virologists. Awaring that viruses frequently target particular cellular pathways to control the cell and encourage viral replication, but each virus may employ a different strategy to accomplish the same control [15,16]. More research on the functional relationships between viruses and host cells will be carried out in the future on the human virome.

The potential interactions between the viral and bacterial communities kept by complex organisms are an essential aspect of virome investigations.

2. The Role of the Viruses in Health and Disease

2.1. Bacteriophages

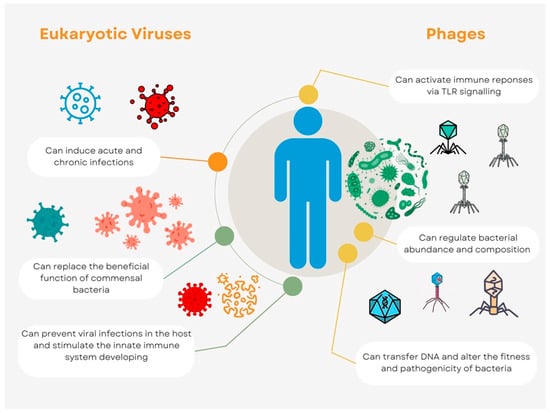

Bacteriophages that attack bacteria are present in the human virome, and these phages might indirectly affect the host by changing the fitness and composition of infected bacteria. Due to the existence of various host bacteria, different anatomical regions may have rather varied phage compositions. Phages are widely spread throughout the human body. The effects of phage predation on the bacterial populations in humans are not well understood. Phage therapy, in which phages are purposefully administered to human patients to cure bacterial infections, provides a window on phage predation and host health. This strategy is becoming increasingly popular as drug-resistant bacteria start to appear [17]. Phage cocktails have recently been employed in numerous investigations to treat bacterial infection in a small number of patients, and their apparent efficacy [18] has inspired bigger clinical trials. Phages can transfer DNA between cells, giving bacterial genomes new functionality and potentially altering their fitness and pathogenicity [19]. Recent investigations on animals and in vitro have suggested that phages might directly interact with the host immune system. Without the involvement of bacteria, immunological responses can be triggered by phages via Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling. Through the nucleotide-sensing receptor TLR9, Lactobacillus, Escherichia, and Bacteroides phages can promote the synthesis of Interleukin 12 (IL-12), IL-6, IL-10, and Interferon γ (IFN) [20,21]. The interactions between phages, bacteria, and the host immune system probably play significant roles in maintaining host immunological homeostasis (Figure 1). Phages can modify bacterial fitness and composition in a way that indirectly affects the host. Some phages and human cell viruses have the ability to integrate into the cells of their respective hosts, sometimes giving the host cells additional capabilities [22].

Figure 1. Virome interconnections with host. The host health is impacted by eukaryotic viruses in both negative and positive ways (green and orange lines, respectively). Phages interact with the host through the bacterial population that is associated with it, and these interactions, either directly or indirectly, could have unknown implications (yellow lines) on human health.

2.2. Eukariotic Viruses

Numerous investigations have found a high level of inter-individual variation in the human virome [23]. The virome, on the other hand, is typically quite consistent over time in a healthy adult, paralleling stability in the cellular microbiome. Virome instability is frequently linked to disease states. Virome populations have a variety of effects on their human hosts. Eukaryotic viruses that attack human cells generate immunological reactions, start infections, and occasionally even illness.

When viruses are detected at locations with a local microbiota, they frequently include both viruses that replicate in the human cells there and viruses that infect the microbiota. It is only now beginning to be determined how much circulation exists between the sites. Often, respiratory viral infections can induce exacerbation of some glomerulonephritis such as IgA nephropathy (IgAN), causing onset of gross hematuria and hypertension. The reasons are not clear but may be partly due to mucosal immune system dysfunction [24,25,26,27]. It is unknown if small circular DNA viruses (Anelloviridae and Redondoviridae) that are common in respiratory samples and can also be discovered in feces emerge in the gut as a result of gastrointestinal tract replication or as a result of salivation [22]. Anelloviridae have been detected in greater frequency in immunocompromised patients, including as lung transplant recipients, Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-positive people, and people on immunosuppressive medications because of inflammatory bowel disease, indicating that they are generally under host immune control [28,29,30]. Another family of extensively occurring tiny circular DNA viruses that are typically identified in the respiratory system is the recently discovered Redondoviridae. They are viruses of the human oral cavity and respiratory tract associated with periodontitis and critical illness [31,32].

3. Virus Infection and Nephropathy

Viral infections are involved in several glomerular diseases, but the pathogenetic links between viral infection and kidney disease are often difficult to establish. The known mechanisms differ for each different viral nephropathy [54]. Generally, acute glomerulonephritis, a viral infection of the glomerulus, causes the local release of cytokines which leads to glomerular cell proliferation [55]. This acute nephropathy resolves spontaneously if the viral infection is rapidly cleared. Chronic glomerulonephritis results from the continuous formation of immune complexes, due to persistent viral infection. Additionally, viral proteins can exacerbate inflammatory conditions and worsen glomerulopathy. Evidence suggests that several viruses such as HIV-1 and hepatitis viruses can cause glomerular damage after both acute and chronic infection. As for cases associated with other viral infections, such as parvovirus B19 and cytomegalovirus (CMV), the mechanisms remain incompletely understood.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms24043897

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!