While IFN- γ is regarded as the primary IDO inducer, there is evidence showing that the expression of IDO can be induced independently of IFN- γ [

56,

57,

58]. In vitro data using HTP-a cells, i.e., a human monocytic cell line, have shown that LPS-induced IPO activation is mediated by an IFN-γ-independent mechanism, including the synergistic effects of TNF-β, IL-6, and IL-β 1 [

57].

Experiments investigating the role of anti-inflammatory cytokines in IDO expression have shown limited and often conflicting results. This might be due to differences in the models used and experimental conditions applied. For instance, IL-10 as one of the major anti-inflammatory cytokines decreased LPS-mediated IDO protein expression in a dose-dependent manner. However, IFN-γ-mediated IDO protein expression was increased by IL-10 in mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) [

59]. This inconsistency may propose that anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 can differentially regulate the distinct mechanisms of IDO induction. However, it has not been demonstrated whether this occurs in the brain. Notably, IFN-γ-treated IDO expression in a transformed mouse neuronal cell line was suppressed by IL-10 [

60]. In addition to the case of IL-10, studies on human monocytes and fibroblasts have suggested that IL-4 can inhibit IDO mRNA induction and IDO activity by IFN-γ. Opposed to this, a study using mouse microglia cells reported that IL-4 can enhance IFN-γ induced IDO mRNA expression, which is diminished by IL-4 antiserum addition [

61]. Along with IL-4, IL-13 which utilizes the same receptor subunit in signaling can potentiate IFN-γ treated IDO mRNA expression in mouse microglia cultures [

61]. Collectively, these findings indicate that responses to anti-inflammatory cytokines in microglia and peripheral myeloid cells are different.

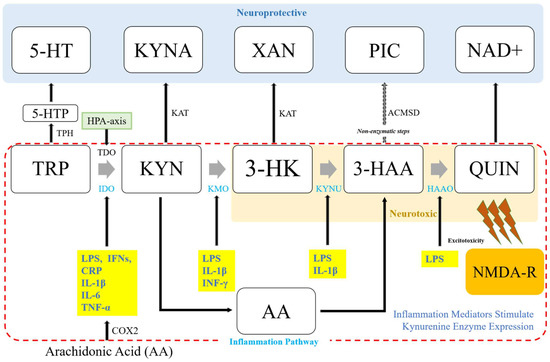

3.2. Kynurenine-3-Monooxygenase (KMO) and Inflammation Mediators

Similar to IDO, pro-inflammatory stimuli may activate KMO enzymes downstream of the pathway. After the systemic inoculation of LPS, KMO expression is induced in rat brain [

56]. KMO is also induced in both IFN-γ treated immortalized murine microglia (N11) and macrophage (MTs) cells. However, KYNU is induced only in MT2 whereas 3-HAAO is not affected [

63]. In human progenitor cells of hippocampus, transcriptional levels of KMO and KYMU are upregulated following IL-1β [

58].

3.3. Kynurenine Aminotransferases (KATs) and Inflammation Mediators

Compared to the expression levels of IDO and other kynurenine enzymes in the neurotoxic branch of the KP, KAT expression is neither elevated nor changed in response to pro-inflammatory stimuli. Systematic LPS inoculation of LPS causes no change in KAT II in rat brain cells [

56]. In immortalized murine microglia (N11) and macrophage (MTs) cells, KAT shows constitutive expression. IFN-γ treatment shows no effect on KAT activity [

63]. In human progenitor cells of hippocampus, IL-1β treatment downregulates only KAT I and III, showing no effect on KAT II [

58].

4. Genetic Links between Inflammation and Kynurenine Metabolism in ADHD

Genetic studies have supported that gene polymorphisms are linked to the inflammatory pathway in ADHD. In a total of 398 subjects, Smith et al. [30] evaluated a set of 164 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from 31 candidate genes and found that two SNPs in the ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor (CNTFR) were associated with the severity of ADHD inattentive symptom. Odell et al. [64] conducted a population-based association study with 546 ADHD patients vs. 546 controls and proposed an association between CNTFR and ADHD in both children and adults. They also reported an association between ADHD and major histocompatibility complex genes, demonstrating the role of inflammation and autoimmunity in this disorder.

Another genome-wide association study for 478 ADHD patients and 880 controls has suggested no significant SNPs [66]. However, a pathway analysis has revealed an association of ADHD with SNPs involved in gene expression regulation, cell adhesion, and inflammation [30]. One study has inspected the genomic overlap between ADHD and other psychiatric disorders in 318 individuals, including 93 who were diagnosed with ADHD, and found a similar inflammation-related genetic signature between ADHD and depression [67].

5. Dysregulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in ADHD

A delay in the development of cortical maturation may cause evident deficits in neuropsychological performances in ADHD [

16]. Although the etiology of this delay is unknown, impaired glial supply to support energy for neuronal activity has been suggested to have a contribution. A recent study on ADHD proposed that patients may carry subsyndromal immunological imbalances such as increased serum IFN-γ and IL-13 levels. It also demonstrated a decreased 3-HK despite normal levels of L-KYN [

26]. Compared to medicated subjects, the alteration of pro-inflammatory cytokine production level and kynurenine metabolism showed a trend toward normalizing in medication naïve subjects. An impaired 3-HK production might be predisposed to reduced activation of microglia and hence impaired neuronal pruning that could bring in developmental delays. These reports might be congruous with early postulations about an imbalance of TRP metabolism in ADHD, suggesting that patients can produce excess serotonin, at least in peripheral compartments [

70].

Although no report has directly explored cytokine and kynurenine profiles at the CNS level in ADHD, a few studies have tried to establish the association between these markers and behavioral endophenotypes by measuring their serum levels. Oades et al. demonstrated that levels of S100b are negatively associated with oppositional and conduct problems in ADHD [

71]. Their study also demonstrated an inverse relationship between S100b and IL-10/IL-16 in children with ADHD. A subsequent study has reported that hyperactivity is strongly correlated with reduced S100b, while attention capacity may be related to IL-13 [

26]. Increased kynurenine and IFN-γ (though reduced TNF-α) are related to faster reaction time, whereas TRP metabolism shows no relation with symptoms.

6. Potential Inflammatory Biomarkers in ADHD

Recently, psychiatry research studies have measured and examined how individual cytokines known to be related to inflammatory processes are related to particular diagnostic categories and related phenotypes. Individual relationships of these markers with various mental disorders in perinatal and offspring outcomes, chronic states, and pre/post-treatment have been examined based on cytokines, C-reactive protein, hormones, neurotrophins, and so on. When interpreting reports of individual studies, it is crucial to consider the extent to which other factors affecting peripheral cytokines are accounted for in specific analyses. Compounding factors including age, sex, weight, smoking, childhood trauma, the timing of blood sampling, medical comorbidities, concurrent medication use, and severity of illness are example variables that should be but are not always indicated in studies. They are possible sources of discrepancy in results [

82,

89].

Peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines can cross the brain through humoral and neural pathways and maintain inflammatory responses via neuroimmune systems. Inflammation-related cytokine changes in the brain are known to cause neurotransmission changes in TRP metabolism and dopaminergic pathways in the brain, similar to those seen in patients with ADHD [

71]. At this point, prenatal exposure to inflammation may restrain brain development resulting from structural changes in the volume of gray matter that can cause permanent neural circuits to fail to mature or bring neuroendocrine changes, thus elevating the risk of ADHD [

95].

Various inflammatory cytokines in the central and peripheral samples have been proposed as feasible potential biomarkers of ADHD risk. Table 2 lists potential inflammatory biomarkers of ADHD risks suggested for youth and adult ADHD patients.

Table 2. Potential inflammatory biomarkers in youth and adult ADHD patients.

| Biomarkers |

Youth |

References |

Adult 1 |

References |

| CRP |

↑ |

[75,76] |

↑ |

[87] |

| IL-1β |

↓ |

[71] |

↔ |

[87] |

| IL-6 |

↑ |

[71,97,98] |

↔ |

[86,99,100] |

| IL-10 |

↑ |

[71,75,98] |

↔ |

[86] |

| IL-13 |

↑ |

[71,75] |

↔ |

[86] |

| IL-16 |

↑ |

[54,71] |

|

|

| TNF-α |

↓ |

[71,86] |

↓ |

[86] |

| Cortisol 2 |

↓ |

[75,76,101,102] |

↓ |

[103] |

Although the most recent research on ADHD biomarkers has suggested the possibility of finding more objective forms of diagnostics compared to the current diagnostic criteria in clinical use today, it remains unclear how these discrete markers are associated with diverse clinical manifestations and different populations that persistently confound research on ADHD. A few observational studies have evaluated different variables without adjusting or controlling confounders to investigate the role of inflammation in the pathophysiology of ADHD, yielding conflicting results. Further research overcoming these limitations of previous research studies performed so far is needed.