Lip inflammation may manifest as mainly reversible cheilitis, mainly irreversible, or cheilitis connected to dermatoses or systemic diseases. Therefore, knowing a patient’s medical history is important, especially whether their lip lesions are temporary, recurrent, or persistent. Sometimes temporary contributing factors, such as climate and weather conditions, can be identified and avoided—exposure to extreme weather conditions (e.g., dry, hot, or windy climates) may cause or trigger lip inflammation. Emotional and psychological stress are also mentioned in the etiology of some lip inflammations (e.g., exfoliative cheilitis) and may be associated with nervous habits such as lip licking.

- lip inflammation

- cheilitis

- perioral dermatitis

- comorbidities

- atopic dermatitis

1. Psychiatric Diseases and Conditions and Common Behavioral Attitudes in Patients with Lip and Perioral Inflammation

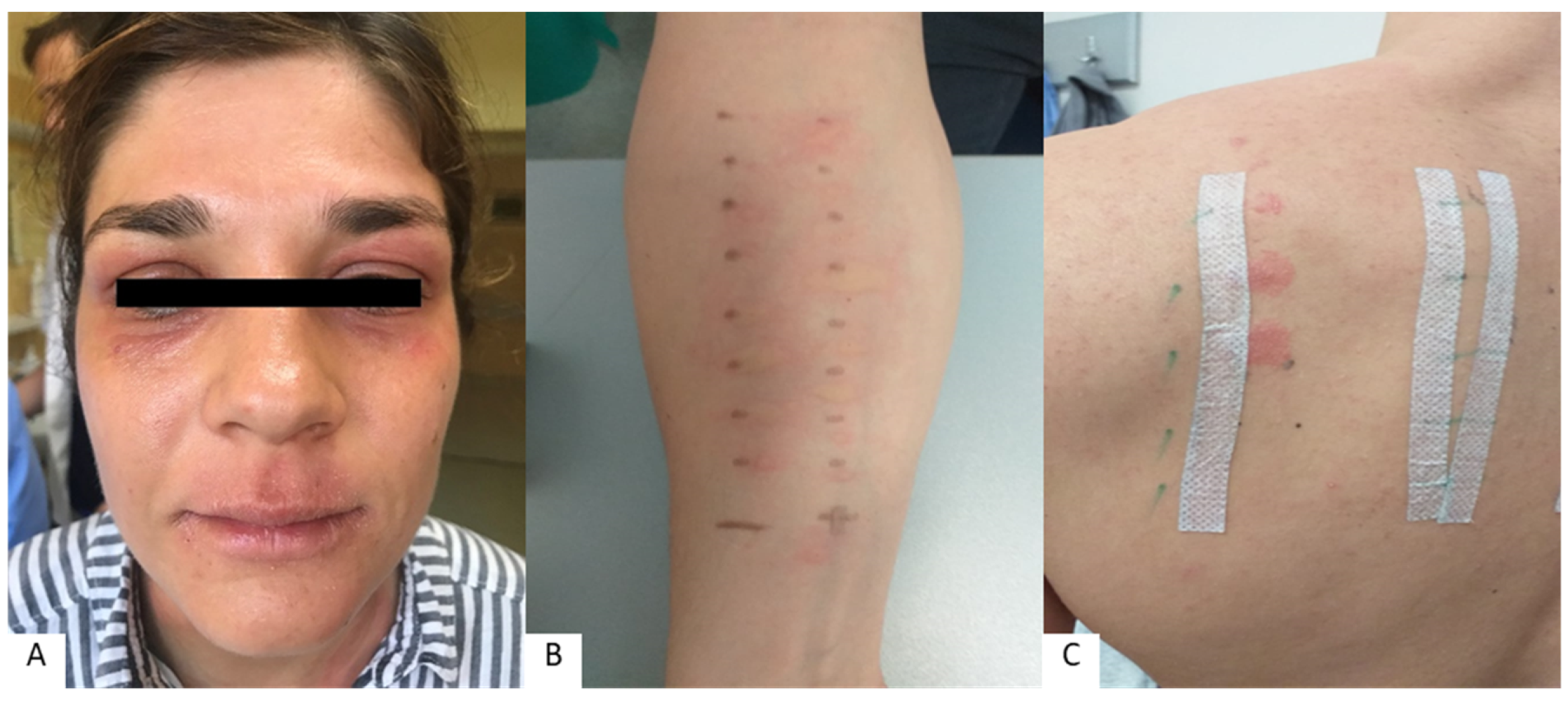

2. Allergies Associated with Lip and Perioral Inflammation

3. Nutritional Deficiencies and Microbiome Changes in Patients with Lip and Perioral Inflammation

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cosmetics10010009

References

- Freeman, S.; Stephens, R. Cheilitis: Analysis of 75 cases referred to a contact dermatitis clinic. Am. J. Contact Dermat. 1999, 10, 198–200.

- Lim, S.W.; Goh, C.L. Epidemiology of eczematous cheilitis at a tertiary dermatological refferal centre in Singapore. Contact Dermat. 2000, 43, 322–326.

- Almazrooa, S.A.; Woo, S.B.; Mawardi, H.; Treister, N. Characterization and mangement of exfoliative cheilitis: A single-centre experience. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2013, 116, 485–489.

- Rodríguez-Blanco, I.; Flórez; Paredes-Suárez, C.; Rodríguez-Lojo, R.; González-Vilas, D.; Ramírez-Santos, A.; Paradela, S.; Conde, I.; Pereiro-Ferreirós, M. Actinic Cheilitis Prevalence and Risk Factors: A Cross-Sectional, Multicentre Study in a Population Aged 45 Years and over in North-West Spain. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2018, 98, 970–974.

- Gheno, J.N.; Martins, M.A.T.; Munerato, M.C.; Hugo, F.N.; Sant’ana Filho, M.; Weissheimer, C.; Carrard, V.C.; Martins, M.D. Oral Mucosal Lesions and Their Association with Sociodemographic, Behavioral, and Health Status Factors. Braz. Oral Res. 2015, 29, S1806-83242015000100289.

- Lopes, M.L.D.d.S.; da Silva Júnior, F.L.; Lima, K.C.; de Oliveira, P.T.; da Silveira, É.J.D. Clinicopathological Profile and Management of 161 Cases of Actinic Cheilitis. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2015, 90, 505–512.

- Bakirtzi, K.; Papadimitriou, I.; Andreadis, D.; Sotiriou, E. Treatment Options and Post-Treatment Malignant Transformation Rate of Actinic Cheilitis: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 3354.

- Vasilovici, A.; Ungureanu, L.; Grigore, L.; Cojocaru, E.; Şenilă, S. Actinic Cheilitis—From Risk Factors to Therapy. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 805425.

- De Lucena, I.M.; Santos, I.d.S.; Daroit, N.B.; Salgueiro, A.P.; Cavagni, J.; Haas, A.N.; Rados, P.V. Sun Protection as a Protective Factor for Actinic Cheilitis: Cross-Sectional Population-Based Study. Oral Dis. 2021, 28, 1802–1810.

- Lupu, M.; Caruntu, A.; Caruntu, C.; Boda, D.; Moraru, L.; Voiculescu, V.; Bastian, A. Non-Invasive Imaging of Actinic Cheilitis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Lip. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 8, 640–646.

- Blagec, T.; Glavina, A.; Špiljak, B.; Bešlić, I.; Bulat, V.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Cheilitis: A Cross-Sectional Study—Multiple Factors Involved in the Aetiology and Clinical Features. Oral Dis. 2022. ahead of print.

- Nico, M.M.S.; Dwan, A.J.; Lourenço, S.V. Ointment pseudo-cheilitis: A disease distinct from factitial cheilitis. A series of 13 patients from São Paolo, Brazil. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2019, 23, 277–281.

- Brown, G.E.; Malakouti, M.; Sorenson, E.; Gupta, R.; Koo, J.Y. Psychodermatology. Adv. Psychosom. Med. 2015, 34, 123–134.

- Panico, R.; Piemonte, E.; Lazos, J.; Gilligan, G.; Zampini, A.; Lanfranchi, H. Oral mucosal lesions in anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and EDNOS. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 96, 178–182.

- Balighi, K.; Daneshpazhooh, M.; Lajevardi, V.; Talebi, S.; Azizpour, A. Cheilitis in acne vulgaris patients with no previous use of systemic retionoid products. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2017, 58, 211–213.

- Daley, T.D.; Gupta, A.K. Exfoliative cheilitis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 1995, 24, 177–179.

- Girijala, R.L.; Falkner, L.; Dalton, S.R.; Martin, B.D. Exfoliative cheilitis as a manifestation of factitial cheilitis. Cureus 2018, 10, 2565.

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Meštrović-Štefekov, J.; Ferček, I.; Pondeljak, N.; Lazić-Mosler, E.; Gašić, A. Atopic Dermatitis Severity, Patient Perception of the Disease, and Personality Characteristics: How Are They Related to Quality of Life? Life 2021, 11, 1434.

- Fishbein, A.B.; Silverberg, J.I.; Wilson, E.J.; Ong, P.Y. Update on Atopic Dermatitis: Diagnosis, Severity Assessment, and Treatment Selection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 91–101.

- Schmidt, D.D.; Zyzansky, S.; Ellner, J.; Kumar, M.L.; Arno, J. Stress as a precipitating factor in subjects with recurrent herpes labialis. J. Fam. Pract. 1985, 20, 359–366.

- Greenberg, S.A.; Schlosser, B.J.; Mirowski, G.W. Diseases of the lips. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 35, e1–e14.

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Pilipović, K.; Crnarić, I.; Šitum, M.; Duvančić, T. Differential diagnosis od cheilitis: How to classify cheilitis? Acta Clin. Croat. 2018, 57, 342–351.

- Scully, C. Dermatoses of the Oral Cavity and Lips. In Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology; Griffiths, C., Barker, J., Bleiker, T., Chalmers, R., Creamer, D., Eds.; Wiley Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2016; pp. 110.1–110.94.

- Collet, E.; Jeudy, G.; Dalac, S. Cheilitis, perioral dermatitis and contact allergy. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2013, 23, 303–307.

- Blagec, T.; Crnarić, I.; Homolak, D.; Pondeljak, N.; Buljan, M.; Lugović-Mihić, L. The association between allergic reactions and lip inflammatory lesions (cheilitis). Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, in press.

- Lugović-Mihić, L.; Blagec, T.; Japundžić, I.; Skroza, N.; Delaš Adžajić, M.; Mravak-Stipetić, M. Diagnostic management of cheilitis: An approach based on a recent proposal for cheilitis classification. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2020, 29, 67–72.

- O’Gorman, S.M.; Torgerson, R.R. Contact allergy in cheilitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, 386–391.

- Zoli, V.; Silvani, S.; Vincenzi, C.; Tosti, A. Allergic contact cheilitis. Contact Dermat. 2006, 54, 296–297.

- Bakula, A.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; Šitum, M.; Turčin, J.; Sinković, A. Contact allergy in the mouth: Diversity of clinical presentations and diagnosis of common allergens relevant to dental practice. Acta Clin. Croat. 2011, 50, 553–561.

- Kim, T.W.; Kim, W.I.; Mun, J.H.; Song, M.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, M.B.; Ko, H.C. Patch testing with dental screening series in oral disease. Ann. Dermatol. 2015, 27, 389–393.

- Budimir, J.; Mravak-Stipetić, M.; Bulat, V.; Ferček, I.; Japundžić, I.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Allergic reactions in oral and perioral diseases- what do allergy skin test results show? Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 127, 40–48.

- Khamaysi, Z.; Bergman, R.; Weltfriend, S. Positive patch test reactions to allergens of the dental series and the relation to the clinical presentations. Contact Dermat. 2006, 55, 216–218.

- Critchlow, W.A.; Chang, D. Cheilitis granulomatosa: A review. Head Neck Pathol. 2014, 8, 209–213.

- Torgerson, R.R.; Davis, M.D.P.; Bruce, A.J.; Farmer, S.A.; Rogers, R.S., 3rd. Contact allergy in oral disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 57, 315–321.

- Cheng, H.S.; Konya, J.; Lobel, E.; Fernandez-Penas, P. Patch testing for cheilitis: A 10-year series. Dermatitis 2019, 30, 347–351.

- Tomljanović-Veselski, M.; Jovanović, I. Najčešći kontaktni alergeni u bolesnika s kontaktnim dermatitisima u području Slavonskog Broda. Med. Jadertina 2006, 36, 45–52.

- Domić, I.; Budimir, J.; Novak, I.; Mravak-Stipetić, M.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Assessment of allergies to food and additives in patients with angioedema, burning mouth syndrome, cheilitis, gingivostomatitis, oral lichenoid reactions, and perioral dermatitis. Acta Clin. Croat. 2021, 60, 276–281.

- Holmes, G.; Freeman, S. Cheilitis caused by contact urticaria to mint flavoured toothpaste. Australas J. Dermatol. 2001, 42, 43–45.

- Oakley, A. Cheilitis. Avaliable online: https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/cheilitis/ (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Ayesh, M.H. Angular cheilitis induced by iron deficiency anemia. Cleve Clin. J. Med. 2018, 85, 581–582.

- Schlosser, B.J.; Pirigyi, M.; Mirowski, G.W. Oral manifestations of hematologic and nutritional diseases. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 44, 183–203.

- Bhutta, B.S.; Hafsi, W. Cheilitis. Available online: https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/37546/ (accessed on 17 November 2022).

- Baumgardner, D.J. Oral Fungal Microbiota: To Thrush and Beyond. J. Patient Cent. Res. Rev. 2019, 6, 252–261.

- Phatak, S.; Redkar, N.; Patil, M.A.; Kuwar, A. Plummer-Vinson Syndrome. Case Rep. 2012, 2012, bcr2012006403.

- Demir, N.; Doğan, M.; Koç, A.; Kaba, S.; Bulan, K.; Ozkol, H.U.; Doğan, S.Z. Dermatological findings of vitamin B12 deficiency and resolving time of these symptoms. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 70–73.

- Kaur, S.; Goraya, J.S. Dermatologic findings of vitamin B(12) deiciency in infants. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, 796–799.

- Glutsch, V.; Hamm, H.; Goebeler, M. Zinc and Skin: An Update. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. 2019, 17, 589–596.

- Gürtler, A.; Laurenz, S. The Impact of Clinical Nutrition on Inflammatory Skin Diseases. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. 2022, 20, 185–202.