Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Optics

Carotenoid compounds are ubiquitous in nature, providing the characteristic colouring of many algae, bacteria, fruits and vegetables. They are a critical component of the human diet and play a key role in human nutrition, health and disease.

- carotenoids

- lutein

- beta carotene

- zeaxanthin

- xanthophyls

- UV-vis

- Raman

1. Introduction

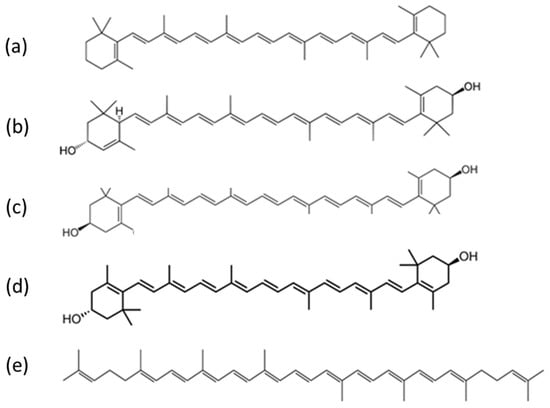

Carotenoids encompass a wide range of fat-soluble pigmented compounds (Figure 1) and are the most widely occurring pigments in nature [1]. They are present across various parts of the ecosystem, including in plants, animals and even micro-organisms. Dietary sources in humans include carotenoid-rich fruits, vegetables, animal fat and other foods. Of the 42 dietary carotenoids, 14 are absorbed, circulated in the blood and deposited in tissue [2], where they play important roles in biological function, particularly as antioxidants and photoprotective agents [3]. Carotenoid consumption is associated with reduced risk of some cancers, including breast, oesophageal and lung [4,5,6,7], coronary heart disease [8,9], stroke [10,11], type 2 diabetes mellitus [12,13,14,15] and asthma in adults and children [16].

Figure 1. Examples of carotenoid compounds of relevance to human health: (a) beta carotene, (b) lutein, (c) zeaxanthin, (d) meso-zeaxanthin and (e) lycopene (public domain images reproduced from Wikimedia Commons).

2. Structure

Carotenoids are hydrocarbons made up of a basic polyene backbone structure, a hydrocarbon chain of 40 sp2 hybridised carbons, the structure of which is represented as alternating double and single bonds between the carbon atoms (Figure 1). The electrons are highly conjugated, giving rise to relatively broad molecular orbitals (MO) and low energy transitions in the visible region that produce their characteristically strong colouring [47,48]. Most naturally existing carotenoids have a trans configuration throughout their conjugated double bonds [49].

Carotenoids are broadly divided into two groups, carotenes, which contain only carbon and hydrogen atoms, e.g., alpha and beta carotenes, and a second group known as the xanthophylls; they contain oxygen atoms in addition to hydrogen and carbon atoms in their structures, e.g., lutein and zeaxanthin [50]. Both forms are poorly soluble in aqueous media and tend to aggregate in J (head to tail) or H (stacked) aggregates [51]. Xanthophylls contain at least one hydroxyl group and are, in general, more polar than carotenes. This has implications for how they aggregate [52,53,54,55] and are transported. In blood circulation, beta carotene and lycopene tend to be predominately localised in the low-density lipoproteins, while lutein and zeaxanthin are more evenly distributed among both low and high-density lipoproteins [56,57].

3. Optical Properties of Carotenoids

The absorption spectra of carotenoids are dominated by strong −* transition in the visible region of the spectrum, the wavelength positioning of which increases with increasing conjugation length [47,58]. For beta carotene in pure ethanol, the absorption maxima at 483 nm, 453 nm and 427 nm (Table 1) are, respectively, attributed to the 0–0, 0–1 and 0–2 transitions of the S0 (11Ag)-S2 (11Bu) vibrational manifold, transitions to the first S1 (21Ag) state being forbidden due to symmetry restrictions [48,54]. S2 state excitation rapidly decays by internal conversion to the S1 state, radiative relaxation from which is similarly symmetry forbidden, and thus carotenoids exhibit negligible fluorescence emission [59].

Table 1 highlights some important optical and chemical properties of dietary carotenoids, including their absorbance maximum, main Raman peak positions, conjugation length, number of hydroxyl groups and conjugated double bonds. Since the position of the longest wavelength absorption transition of carotenoids should normally be directly proportional to their conjugation length [58], zeaxanthin, which is the longer xanthophyll, should be shifted to the red when compared with lutein, especially if all other conditions, such as solvent type and temperature are kept constant for both carotenoids [58,60]. However, because of their lipophilic nature, carotenoids tend to aggregate in hydrophilic environments via weak intermolecular forces such as van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding and dipole forces [61]. This results in shifts in the absorption spectrum towards the red or blue region [51], depending on whether they form strongly (H) or weakly (J) coupled aggregates [61,62].

Table 1. Summary of some optical and chemical properties of carotenoids.

| Carotenoid | Absorbance λ Max in Ethanol (nm) [55,63,64,65] | Main Raman Peaks Positions (cm−1) [66] | Conjugation Length (n) [60,67] | Hydroxyl Groups | Number of Conjugated Double Bonds [68,69,70] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta carotene | ~427, 453, 483 | ~1000, 1160, 1520 | 9.6 | none | 11 |

| Lycopene | ~447, 474, 504 | ~1000, 1160, 1520 | 11 | none | 11 |

| Lutein | ~424, 445, 472 | ~1000, 1160, 1520 | 9.3 | 2 | 10 |

| Zeaxanthin | ~424, 445, 472 | ~1000, 1160, 1520 | 9.6 | 2 | 11 |

The longest wavelength absorption maximum of beta carotene is shifted from ~476 nm in ethanol to ~515 nm in 1:1 ethanol–water solution due to J aggregation, while the 453 nm and 427 nm peaks are blue-shifted, attributed to H-aggregation [52,53,54,55]. Similar spectral shifting in a range of solvents has been documented depending on polarising efficiencies [71,72,73]. The UV-visible absorption spectrum of beta carotene in solution is also pressure dependent, with the longest wavelength absorption maximum shifting as far as ~580 nm in carbon disulphide solution at 0.96 GPa [74]. In H aggregates of zeaxanthin, prepared in ethanol:water mixtures, the UV-vis spectrum is dominated by a strong feature at 370 nm, while in the J aggregate, formed in 1:9 THF:water solutions, the longest wavelength absorption maximum is shifted from 485 nm to ~510 nm [75,76]. A similar red shift is seen in J aggregates of lutein [77].

Both beta carotene and the xanthophylls, lutein and zeaxanthin, when dissolved in hydrated organic solvents, can form either of the two kinds of aggregates depending on the nature of the solvent [62]. For instance, when incorporated into lipid bilayers, xanthophylls appear mostly in the monomeric form at concentrations below 0.5 mol%. With higher concentrations, they tend to form mostly H aggregates [62]. It was also recently shown that as a result of carotenoid–protein interactions, absorption changes consistent with J-type aggregation can occur [51,62]. The presence of two hydroxyl groups in a carotenoid (e.g., lutein and zeaxanthin) generally promotes the formation of the H-type of aggregates [51]. When the hydrogen-bond formation is intercepted, for example, by esterification or a lack of end-ring functional groups, J-type aggregates could be formed [51]. Additionally, zeaxanthin is less polar than lutein, making it easier to form H-type aggregates in water/ethanol mixtures than lutein [51,62].

In the bloodstream, carotenoids are predominantly associated with lipoproteins, which are bound by albumin [43,78,79]. In addition to the solubilising effect, facilitating transport around the body, the complexation has been shown to protect the electron-rich molecules from oxidation [80]. When complexed with bovine serum albumin (BSA), the longest wavelength absorption maximum of beta carotene has been observed at ~515 nm, indicating the presence of J aggregates [80,81]. A similar absorption profile was observed for zeaxanthin, while lutein showed a strong, blue-shifted absorption maximum, characteristic of H-aggregates [81]. In beta carotene-bound albumin nanoparticles, the absorption profile was seen to extend further to the red, towards 600 nm [82].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules27249017

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!