Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a eukaryotic organelle, is the major site of protein biosynthesis. The disturbance of ER function by biotic or abiotic stress triggers the accumulation of misfolded or unfolded proteins in the ER. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is the best-studied ER stress response. This transcriptional regulatory system senses ER stress, activates downstream genes that function to mitigate stress, and restores homeostasis. In addition to its conventional role in stress responses, reports indicate that the UPR is involved in plant growth and development.

- endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

- ER stress

- unfolded protein response (UPR)

- gene regulation

- stress response

- defense

- vegetative growth

- reproduction

1. Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a eukaryotic organelle that serves as a major assembly site for protein superstructures [1]. At least one-third of cellular proteins are processed at the ER and directed toward secretory pathways, where they are folded into their functional forms [2]. Various stressful stimuli trigger fluctuations in the cellular environment that cause misfolded and unfolded proteins to accumulate inside the ER, resulting in ER stress.

The ER quality control (ERQC) system monitors and fortifies ER function to maintain homeostasis [3][4][5]. In this system, ER-resident proteins such as chaperones, cochaperones, lectins, redox enzymes, and glucosidases have designated roles in protein processing. The ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathway reduces the unfolded-protein load through a ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal protein catabolic process. The overaccumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER triggers gene regulatory machinery that enforces ER function by promoting the expression of ERQC components, namely, the unfolded protein response (UPR).

2. Two Distinct Plant UPR Pathways

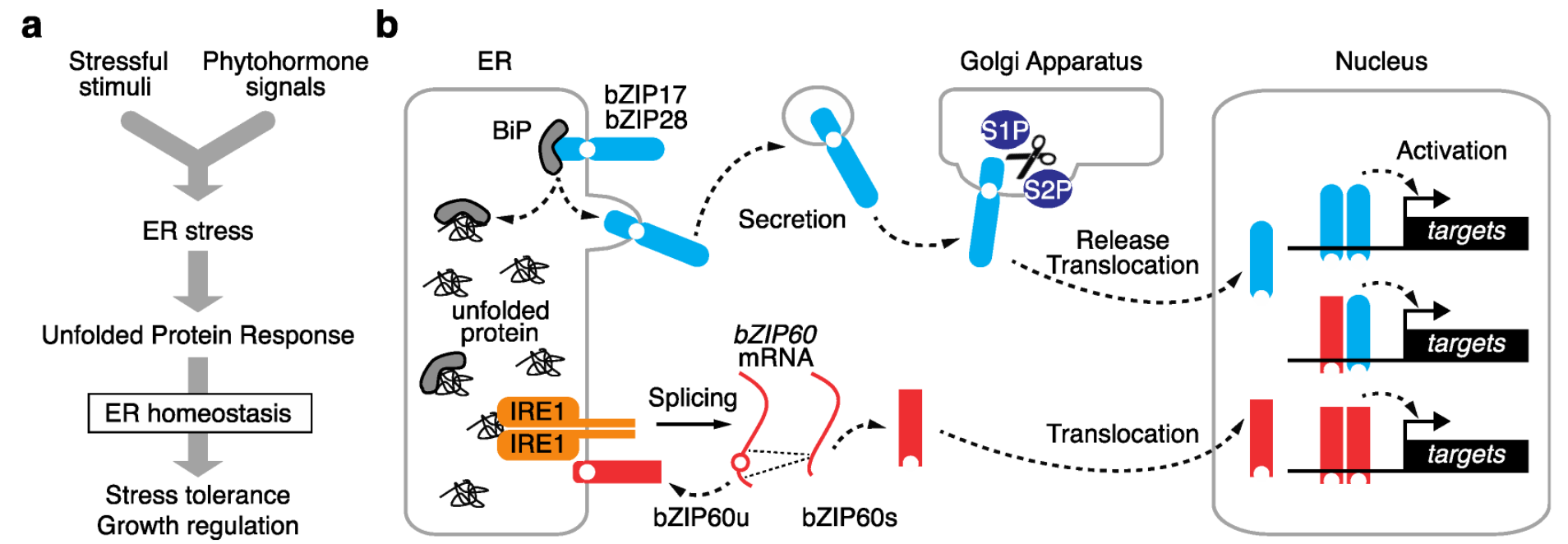

Eukaryotes have developed multiple UPR pathways that communicate with the nucleus and vary by evolutionary lineage [6]. In vascular plants, two eukaryote-wide pathways have been identified with some plant-specific features. Each UPR pathway consists of unique components, including stress sensors, activators, and transcription factors. A dedicated subclade of basic leucine zipper (bZIP)-type transcription factors is involved in the UPR, of which bZIP17, bZIP28, and bZIP60 have been identified in Arabidopsis. These bZIPs are localized to the ER membrane, where two distinct machineries activate them for translocation into the nucleus (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic view of the plant ER stress signaling pathway. (a) The plant ER stress response transduces both exogenous stress stimuli and endogenous phytohormone signals into the unfolded protein response (UPR) to govern stress tolerance and growth regulation. (b) Two eukaryote-wide UPR pathways are activated by distinct pathways. Arabidopsis bZIP17 and bZIP28 are activated by post-translational proteolysis at the Golgi apparatus, and bZIP60 is activated by alternative splicing. The activated bZIPs are translocated to the nucleus, where they activate downstream target genes.

2.1. Proteolysis-Dependent UPR Pathway

Arabidopsis bZIP17 and bZIP28 are counterparts of mammalian activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and mediate a UPR pathway via post-translational proteolysis [5]. In each of these transcription factors, the N-terminus containing the bZIP domain faces the cytosol and is connected by a transmembrane domain to the C-terminal tail, which is exposed to the ER lumen [6][7]. In response to increasing ER stress levels, these two bZIPs are secreted into the Golgi apparatus, where proteases SITE-1 PROTEASE (S1P) and S2P cleave the proteins between the bZIP and transmembrane domains. The released N-terminus possessing the bZIP domain is freely translocated into the nucleus and activates downstream genes involved in the UPR [6][7] (Figure 1b).

In a paralogous manner to that observed in human ATF6, the lumen-facing region of Arabidopsis bZIP28 functions as a stress sensor [8]. During ER homeostasis, ER-resident chaperone BINDING PROTEIN 3 (BiP3) binds to the lumen-facing region of bZIP28, preventing its activation. When ER stress increases, BiP3 preferentially binds to unfolded proteins, allowing bZIP28 to be secreted into the Golgi apparatus, where it is activated (Figure 1b). Further details have not been fully elucidated, but recent studies identified a key ER-resident chaperone and a novel chemical affecting ATF6 trafficking in mammals [9][10]. This could provide insight into the underlying mechanism in plants.

2.2. mRNA Splicing-Dependent UPR Pathway

The other UPR pathway is mediated by Arabidopsis bZIP60, which is activated by alternative splicing [11][12][13]. bZIP60 counterparts exist in most eukaryotes, from budding yeast to mammals, and are known as X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) [6]. In the absence of activation by ER stress, the major isoform of bZIP60 mRNA encodes a protein with a transmembrane domain that anchors it to the ER membrane, thus compromising its transcription factor activity. When ER stress is elevated, stress sensor and activator INOSITOL-REQUIRING ENZYME 1 (IRE1) in the ER lumen specifically splices the bZIP60 mRNA to remove its transmembrane domain, allowing for bZIP60 to migrate into the nucleus to activate the UPR (Figure 1b). Two major IRE1 homologs (IRE1a and IRE1b) were extensively studied in Arabidopsis [13][14][15][16]. Both IRE1s are transmembrane proteins that localize to the ER membrane, where their ER lumen-facing domain functions as a stress sensor, and their cytosol-facing domain splices or degrades target mRNAs. These two homologs are functionally redundant during bZIP60 activation in response to ER stress. A third IRE1 homolog in Arabidopsis was recently characterized. Unlike IRE1a and IRE1b, IRE1c lacks the lumen-facing domain that functions as the ER stress sensor; however, biochemical and genetic experiments revealed that IRE1c couples with IRE1b to play critical roles in gametogenesis [17][18]. Arabidopsis lyrata, a close relative of Arabidopsis thaliana, contains a fourth IRE1c-like homolog whose role in the UPR is unclear [17]. By contrast, only a single IRE1 copy has been identified in rice (Oryza sativa subsp. japonica), and the knockout of this gene is lethal [19].

In addition to bZIPs, three NAC (NAM, ATAC, and CUC)-type transcription factors (NAC062, NAC089, and NAC103) play regulatory roles in the plant UPR [20][21][22]. The expression of these genes is induced by ER stress, and their expression is diminished in bzip60 single mutants [20][22][23], suggesting that these NACs may function as subordinates of the IRE1-bZIP60 pathway. However, the translocation mechanism of these NACs from the ER to the nucleus remains uncertain; novel plant-specific pathways are expected to be discovered upon further investigation.

2.3. Modes of Action of UPR bZIP Dimers

bZIP transcription factors form dimers that bind to their target DNA sequences [24]. These transcription factors can form homo- and heterodimers even across subclade boundaries. Different dimers are thought to have different target preferences that could result in diverse downstream gene regulatory pathways. The three UPR bZIPs (bZIP17, bZIP28, and bZIP60) also form both homo- and heterodimers in every possible combination [23][25]; their different modes of action have been analyzed using combinations of their knockout mutants.

In Arabidopsis, bZIP28 and bZIP60 are commonly accepted as the foremost combination governing canonical UPR downstream regulation [7][26]. The expression of most known ERQC component genes was impaired by the double mutation of bZIP28 and bZIP60 (bzip2860). A significant number of genes, including BiP3, CNX1 (CALNEXIN 1), and ERO1 (ER OXIDOREDUCTIN 1), also fully lost their stress-inducible expression in the double mutant [23]. Moreover, these two bZIPs have their own specific targets. A single bzip28 mutation was sufficient to inhibit the stress-responsive expression of CRT2 (CALRETICULIN 2), SHD (SHEPHERD), and SDF2 (STOMATAL-DERIVED FACTOR2), whereas the single bzip60 mutation abolished the stress-responsive induction of PDI9 (PROTEIN DISULFIDE ISOMERASE 9), SAR1A (SECRETION-ASSOCIATED RAS 1A), and SEC31A (SECRETORY 31A) [23][25][27]. Consistently, bzip2860 plants showed reduced tolerance to chemical-induced ER stress, and the bzip28 and bzip60 single mutants had a similar, but weaker, phenotype [28].

bZIP17, a homolog of bZIP28, is also a transcriptional activator that responds to ER stress [29], although its role in the canonical UPR appears to be auxiliary to that of other UPR bZIPs. Under ER stress conditions, transcriptomic changes in vegetative tissues caused by the double mutation of bZIP17 and bZIP60 (bzip1760) are only slightly different from those caused by the single bzip60 mutation, and the single bzip17 mutation also resulted in only subtle changes [23]. Recent studies revealed that bZIP17 plays important roles in inflorescence tissues [30][31][32], with specific target genes including HOMEOBOX 7 (HB-7) and DELTA1-PYRROLINE-5-CARBOXYLATE SYNTHASE 1 (P5CS1) [32][33].

3. UPR Action in Stress Responses

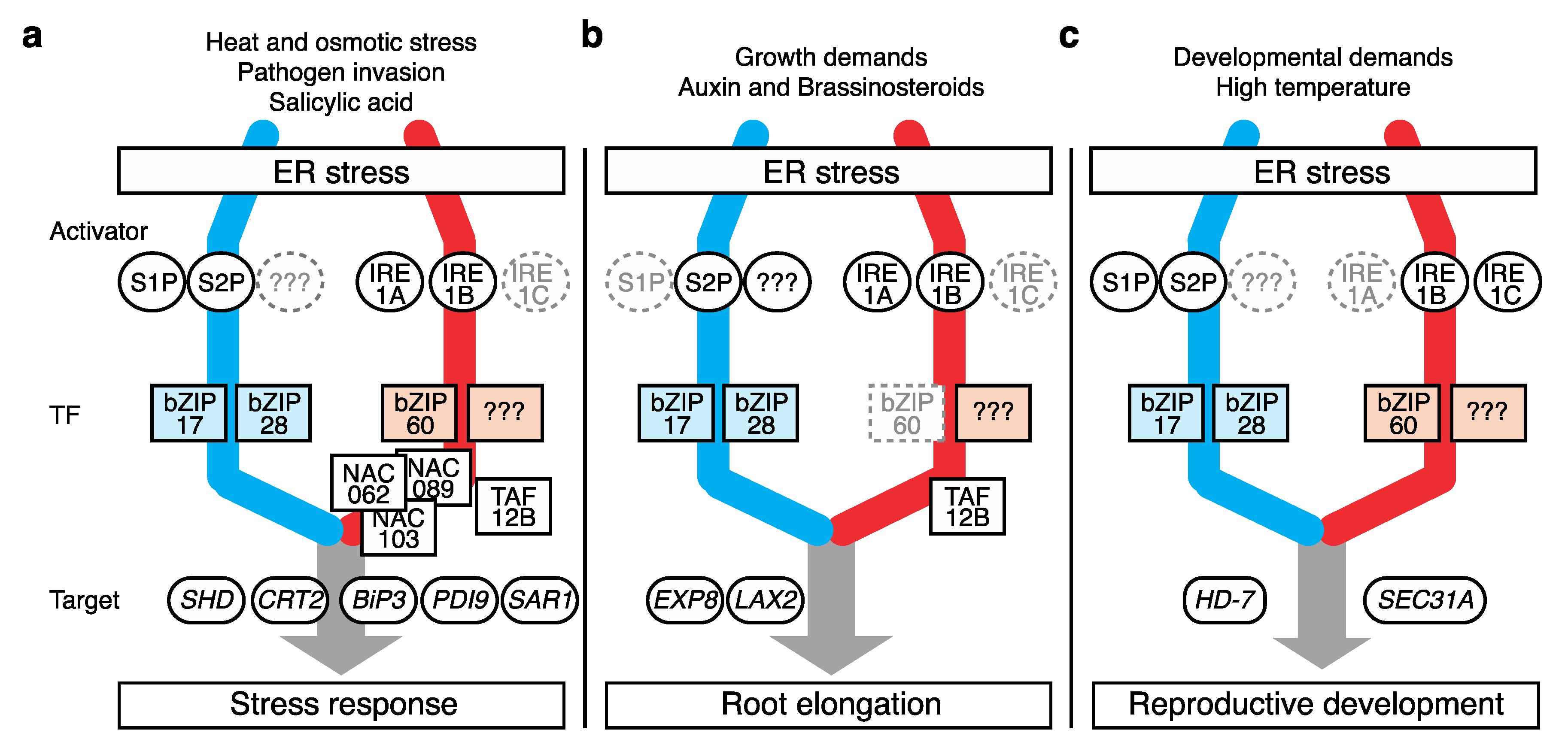

While monitoring ER homeostasis, the UPR responds to a broad range of signals, including stress stimuli, phytohormonal reactions, and developmental phase changes, which interfere with protein folding. By enforcing ERQC, the UPR imparts tolerance toward these stressors in plants (Figure 2 and Table 1).

Figure 2. Different modes of plant UPR action. Plant UPR components governing biological processes including (a) canonical stress response, (b) root elongation, and (c) reproductive development. Components with an auxiliary role are marked in gray. Suspected but unknown components are marked as “???”. Only representative targets are shown. The color scheme for the two UPR pathways is the same as that in Figure 1.

Table 1. Physiological defects and characteristics of knockout mutants of UPR components in Arabidopsis (A. thaliana).

| Knockout Mutant | Viability | Stress Tolerance | Primary Root Growth (% of Wild Type) | Other Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bzip17 | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to heat [32] and salinity [31] | 100% [16][23] | Ectopic expression enhanced salinity tolerance [29] |

| bzip28 | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to heat [34] | 100% [16][23] | - |

| bzip1728 | n.s. | - | 10% [23][35] | Shoot growth defect recovered by grafting to wild-type roots [35] |

| bzip60 | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to heat [36], viral infection [37] | 100% [16] | - |

| bzip1760 | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to viral infection [38] | 100% [16][23] | - |

| bzip2860 | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to heat [30] | 100% [16][23] | - |

| bzip172860 | Lethal [23] | n.a. | n.a. | - |

| s1p | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to salinity [39] | 100% [39] | - |

| s2p | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to heat [36], drought [40] | 40% [40] | - |

| s1p2p | n.s. | n.a. | 40% [23] | - |

| ire1a | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to pathogen [41] | 100% [16] | - |

| ire1b | One lethal mutant [15][42] | n.s. | 100% [16] | - |

| ire1c | n.s. | n.a. | 100% [18] | - |

| ire1ab | n.s. | Reduced tolerance to heat [36], viral infection [37] | 60% [43] | - |

| ire1bc | Decreased pollen viability [17] | n.s. | 100% [17] | - |

| ire1abc | Lethal [17][18] | n.a. | n.a. | - |

| bzip17ire1a | n.s. | n.s. | 100% [44] | - |

| bzip17ire1b | n.s. | n.a. | 60% [44] | - |

| bzip17ire1ab | n.s. | n.a. | 10% [44] | Delayed flowering [44] |

| bzip28ire1ab | Lethal [16] | n.a. | n.a. | - |

| bzip60ire1ab | n.s. | n.a. | 60% [16] | Similar genetic defects to ire1ab |

n.s., no significant difference from the wild type. n.a., not applicable.

Heat stress is one of the best-studied UPR triggers due to its striking effect on protein structure. Single mutants bzip17, bzip28, and s2p have reduced heat tolerance [32][34][40]. The double mutants of bZIP28 and bZIP60 (bzip2860), and IRE1a and b (ire1ab) are especially vulnerable to high temperatures during reproduction [30][36]. Furthermore, both proteolysis-dependent bZIP28 and splicing-dependent bZIP60 activation can be induced by heat-shock treatment [12][34].

Osmotic stress is another UPR trigger in plants. High-salinity and high-osmolarity conditions trigger the activation of bZIP17 and its translocation to the nucleus [31][39], and the ectopic expression of bZIP17 improved plant resilience to salt stress [29]. Salt-stress-induced bZIP17 proteolysis was diminished in the single s1p mutant [39], and the single s2p mutant also exhibited reduced tolerance to desiccation [40] and reduced sensitivity to abscisic acid (ABA), the plant hormone that mediates drought stress signaling [33].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants11233197

References

- Saheki, Y.; de Camilli, P. Endoplasmic Reticulum–Plasma Membrane Contact Sites. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 659–684.

- Anelli, T.; Sitia, R. Protein Quality Control in the Early Secretory Pathway. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 315–327.

- Phillips, B.P.; Gomez-Navarro, N.; Miller, E.A. Protein Quality Control in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 65, 96–102.

- Strasser, R. Protein Quality Control in the Endoplasmic Reticulum of Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2018, 69, 147–172.

- Howell, S.H. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Responses in Plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 477–499.

- Howell, S.H. Evolution of the Unfolded Protein Response in Plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 2625–2635.

- Pastor-Cantizano, N.; Ko, D.K.; Angelos, E.; Pu, Y.; Brandizzi, F. Functional Diversification of ER Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 123–136.

- Srivastava, R.; Deng, Y.; Shah, S.; Rao, A.G.; Howell, S.H. BINDING PROTEIN Is a Master Regulator of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Sensor/Transducer BZIP28 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 1416–1429.

- Gallagher, C.M.; Walter, P. Ceapins Inhibit ATF6α Signaling by Selectively Preventing Transport of ATF6α to the Golgi Apparatus during ER Stress. eLife 2016, 5, e11880.

- Oka, O.B.; van Lith, M.; Rudolf, J.; Tungkum, W.; Pringle, M.A.; Bulleid, N.J. ERp18 Regulates Activation of ATF6α during Unfolded Protein Response. EMBO J. 2019, 38, e100990.

- Iwata, Y.; Koizumi, N. An Arabidopsis Transcription Factor, AtbZIP60, Regulates the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response in a Manner Unique to Plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 5280–5285.

- Deng, Y.; Humbert, S.; Liu, J.-X.; Srivastava, R.; Rothstein, S.J.; Howell, S.H. Heat Induces the Splicing by IRE1 of a MRNA Encoding a Transcription Factor Involved in the Unfolded Protein Response in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7247–7252.

- Nagashima, Y.; Mishiba, K.; Suzuki, E.; Shimada, Y.; Iwata, Y.; Koizumi, N. Arabidopsis IRE1 Catalyses Unconventional Splicing of BZIP60 MRNA to Produce the Active Transcription Factor. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 29.

- Koizumi, N.; Martinez, I.M.; Kimata, Y.; Kohno, K.; Sano, H.; Chrispeels, M.J. Molecular Characterization of Two Arabidopsis Ire1 Homologs, Endoplasmic Reticulum-Located Transmembrane Protein Kinases. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 949–962.

- Chen, Y.; Brandizzi, F. AtIRE1A/AtIRE1B and AGB1 Independently Control Two Essential Unfolded Protein Response Pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012, 69, 266–277.

- Deng, Y.; Srivastava, R.; Howell, S.H. Protein Kinase and Ribonuclease Domains of IRE1 Confer Stress Tolerance, Vegetative Growth, and Reproductive Development in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19633–19638.

- Mishiba, K.; Iwata, Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Matsumura, A.; Nishioka, N.; Hirata, R.; Koizumi, N. Unfolded Protein-Independent IRE1 Activation Contributes to Multifaceted Developmental Processes in Arabidopsis. Life Sci. Alliance 2019, 2, e201900459.

- Pu, Y.; Ruberti, C.; Angelos, E.R.; Brandizzi, F. AtIRE1C, an Unconventional Isoform of the UPR Master Regulator AtIRE1, Is Functionally Associated with AtIRE1B in Arabidopsis Gametogenesis. Plant Direct 2019, 3, e00187.

- Wakasa, Y.; Hayashi, S.; Ozawa, K.; Takaiwa, F. Multiple Roles of the ER Stress Sensor IRE1 Demonstrated by Gene Targeting in Rice. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 944.

- Yang, Z.-T.; Lu, S.-J.; Wang, M.-J.; Bi, D.-L.; Sun, L.; Zhou, S.-F.; Song, Z.-T.; Liu, J.-X. A Plasma Membrane-Tethered Transcription Factor, NAC062/ANAC062/NTL6, Mediates the Unfolded Protein Response in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2014, 79, 1033–1043.

- Yang, Z.-T.; Wang, M.-J.; Sun, L.; Lu, S.-J.; Bi, D.-L.; Sun, L.; Song, Z.-T.; Zhang, S.-S.; Zhou, S.-F.; Liu, J.-X. The Membrane-Associated Transcription Factor NAC089 Controls ER-Stress-Induced Programmed Cell Death in Plants. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004243.

- Sun, L.; Yang, Z.-T.; Song, Z.-T.; Wang, M.-J.; Sun, L.; Lu, S.-J.; Liu, J.-X. The Plant-Specific Transcription Factor Gene NAC103 Is Induced by BZIP60 through a New Cis-Regulatory Element to Modulate the Unfolded Protein Response in Arabidopsis. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 76, 274–286.

- Kim, J.-S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. ER-Anchored Transcription Factors BZIP17 and BZIP28 Regulate Root Elongation. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2221–2230.

- Dröge-Laser, W.; Snoek, B.L.; Snel, B.; Weiste, C. The Arabidopsis BZIP Transcription Factor Family—An Update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 36–49.

- Liu, J.-X.; Howell, S.H. BZIP28 and NF-Y Transcription Factors Are Activated by ER Stress and Assemble into a Transcriptional Complex to Regulate Stress Response Genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 782–796.

- Iwata, Y.; Koizumi, N. Plant Transducers of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Unfolded Protein Response. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 720–727.

- Iwata, Y.; Fedoroff, N.V.; Koizumi, N. Arabidopsis BZIP60 Is a Proteolysis-Activated Transcription Factor Involved in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 3107–3121.

- Ruberti, C.; Lai, Y.; Brandizzi, F. Recovery from Temporary Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Plants Relies on the Tissue-Specific and Largely Independent Roles of BZIP28 and BZIP60, as Well as an Antagonizing Function of BAX-Inhibitor 1 upon the pro-Adaptive Signaling Mediated by BZIP28. Plant J. 2018, 93, 155–165.

- Liu, J.-X.; Srivastava, R.; Howell, S.H. Stress-Induced Expression of an Activated Form of AtbZIP17 Provides Protection from Salt Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2008, 31, 1735–1743.

- Zhang, S.-S.; Yang, H.; Ding, L.; Song, Z.-T.; Ma, H.; Chang, F.; Liu, J.-X. Tissue-Specific Transcriptomics Reveals an Important Role of the Unfolded Protein Response in Maintaining Fertility upon Heat Stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2017, 29, 1007–1023.

- Cifuentes-Esquivel, N.; Celiz-Balboa, J.; Henriquez-Valencia, C.; Mitina, I.; Arraño-Salinas, P.; Moreno, A.A.; Meneses, C.; Blanco-Herrera, F.; Orellana, A. BZIP17 Regulates the Expression of Genes Related to Seed Storage and Germination, Reducing Seed Susceptibility to Osmotic Stress. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 6857–6868.

- Gao, J.; Wang, M.-J.; Wang, J.-J.; Lu, H.-P.; Liu, J.-X. BZIP17 Regulates Heat Stress Tolerance at Reproductive Stage in Arabidopsis. aBIOTECH 2022, 3, 1–11.

- Zhou, S.-F.; Sun, L.; Valdés, A.E.; Engström, P.; Song, Z.-T.; Lu, S.-J.; Liu, J.-X. Membrane-Associated Transcription Factor Peptidase, Site-2 Protease, Antagonizes ABA Signaling in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 188–197.

- Gao, H.; Brandizzi, F.; Benning, C.; Larkin, R.M. A Membrane-Tethered Transcription Factor Defines a Branch of the Heat Stress Response in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16398–16403.

- Moreno, A.A.; Mukhtar, M.S.; Blanco, F.; Boatwright, J.L.; Moreno, I.; Jordan, M.R.; Chen, Y.; Brandizzi, F.; Dong, X.; Orellana, A.; et al. IRE1/BZIP60-Mediated Unfolded Protein Response Plays Distinct Roles in Plant Immunity and Abiotic Stress Responses. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31944.

- Deng, Y.; Srivastava, R.; Quilichini, T.D.; Dong, H.; Bao, Y.; Horner, H.T.; Howell, S.H. IRE1, a Component of the Unfolded Protein Response Signaling Pathway, Protects Pollen Development in Arabidopsis from Heat Stress. Plant J. 2016, 88, 193–204.

- Gayral, M.; Arias Gaguancela, O.; Vasquez, E.; Herath, V.; Flores, F.J.; Dickman, M.B.; Verchot, J. Multiple ER-to-Nucleus Stress Signaling Pathways Are Activated during Plantago Asiatica Mosaic Virus and Turnip Mosaic Virus Infection in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2020, 103, 1233–1245.

- Liu, J.-X.; Srivastava, R.; Che, P.; Howell, S.H. Salt Stress Responses in Arabidopsis Utilize a Signal Transduction Pathway Related to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signaling: Salt Stress Elicits ER Stress Response. Plant J. 2007, 51, 897–909.

- Zhang, L.; Chen, H.; Brandizzi, F.; Verchot, J.; Wang, A. The UPR Branch IRE1-BZIP60 in Plants Plays an Essential Role in Viral Infection and Is Complementary to the Only UPR Pathway in Yeast. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, e1005164.

- Zhou, J.-M.; Zhang, Y. Plant Immunity: Danger Perception and Signaling. Cell 2020, 181, 978–989.

- Nagashima, Y.; Iwata, Y.; Ashida, M.; Mishiba, K.; Koizumi, N. Exogenous Salicylic Acid Activates Two Signaling Arms of the Unfolded Protein Response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 1772–1778.

- Lu, D.-P.; Christopher, D.A. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Activates the Expression of a Sub-Group of Protein Disulfide Isomerase Genes and AtbZIP60 Modulates the Response in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2008, 280, 199–210.

- Hayashi, S.; Wakasa, Y.; Takaiwa, F. Functional Integration between Defence and IRE1-Mediated ER Stress Response in Rice. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 670.

- Kim, J.-S.; Sakamoto, Y.; Takahashi, F.; Shibata, M.; Urano, K.; Matsunaga, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis TBP-ASSOCIATED FACTOR 12 Ortholog NOBIRO6 Controls Root Elongation with Unfolded Protein Response Cofactor Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120219119.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!