- asteroid

- schwarzschild

- ˈʃvaɐ̯tsʃɪlt

Basic Information

(Oct 1873–May 1916)

Location: Frankfurt am Main, German Empire

1. Introduction

Karl Schwarzschild (9 October 1873 – 11 May 1916) was a Germany physicist and astronomer. He was also the father of astrophysicist Martin Schwarzschild.

Schwarzschild provided the first exact solution to the Einstein field equations of general relativity, for the limited case of a single spherical non-rotating mass, which he accomplished in 1915, the same year that Einstein first introduced general relativity. The Schwarzschild solution, which makes use of Schwarzschild coordinates and the Schwarzschild metric, leads to a derivation of the Schwarzschild radius, which is the size of the event horizon of a non-rotating black hole.

Schwarzschild accomplished this while serving in the German army during World War I. He died the following year from the autoimmune disease pemphigus, which he developed while at the Russian front. Various forms of the disease particularly affect people of Ashkenazi Jewish origin.

Asteroid 837 Schwarzschilda is named in his honour, as is the large crater Schwarzschild, on the far side of the Moon.[1]

2. Life

Karl Schwarzschild was born on the 9th of October 1873 in Frankfurt on Main to Jewish parents. His father was active in the business community of the city, and the family had ancestors in the city dating back to the sixteenth century.[2] Karl attended a Jewish primary school until 11 years of age. He was something of a child prodigy, having two papers on binary orbits (celestial mechanics) published before he was sixteen.[3] He studied at Strasbourg and Munich, obtaining his doctorate in 1896 for a work on Henri Poincaré's theories.

From 1897, he worked as assistant at the Kuffner Observatory in Vienna.

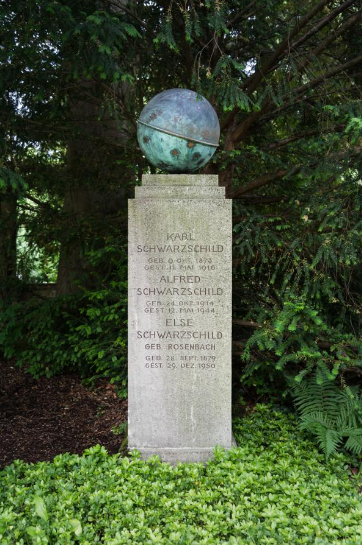

From 1901 until 1909 he was a professor at the prestigious institute at Göttingen, where he had the opportunity to work with some significant figures, including David Hilbert and Hermann Minkowski. Schwarzschild became the director of the observatory in Göttingen. He married Else Rosenbach, the daughter of a professor of surgery at Göttingen, in 1909, and later that year moved to Potsdam, where he took up the post of director of the Astrophysical Observatory. This was then the most prestigious post available for an astronomer in Germany. He and Else had three children, Agathe (who was a Classics professor at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand), Martin (who went on to become a professor of astronomy at Princeton University), and Alfred.

From 1912, Schwarzschild was a member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

At the outbreak of World War I in 1914 he joined the German army, despite being over 40 years old. He served on both the western and eastern fronts, rising to the rank of lieutenant in the artillery.

While serving on the front in Russia in 1915, he began to suffer from a rare and painful autoimmune skin disease called pemphigus. Nevertheless, he managed to write three outstanding papers, two on the theory of relativity and one on quantum theory. His papers on relativity produced the first exact solutions to the Einstein field equations, and a minor modification of these results gives the well-known solution that now bears his name — the Schwarzschild metric.

Schwarzschild's struggle with pemphigus may have eventually led to his death on 11 May 1916.

3. Work

Thousands of dissertations, articles, and books have since been devoted to the study of Schwarzschild's solutions to the Einstein field equations. However, although Schwarzschild's best known work lies in the area of general relativity, his research interests were extremely broad, including work in celestial mechanics, observational stellar photometry, quantum mechanics, instrumental astronomy, stellar structure, stellar statistics, Halley's comet, and spectroscopy.[4]

Some of his particular achievements include measurements of variable stars, using photography, and the improvement of optical systems, through the perturbative investigation of geometrical aberrations.

3.1. Physics of Photography

While at Vienna in 1897, Schwarzschild developed a formula, now known as the Schwarzschild law, to calculate the optical density of photographic material. It involved an exponent now known as the Schwarzschild exponent, which is the [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] in the formula:

[math]\displaystyle{ i = f ( I\cdot t^p ) }[/math]

(where [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is optical density of exposed photographic emulsion, a function of [math]\displaystyle{ I }[/math], the intensity of the source being observed, and [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math], the exposure time, with [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] a constant). This formula was important for enabling more accurate photographic measurements of the intensities of faint astronomical sources.

3.2. Electrodynamics

According to Wolfgang Pauli (Theory of relativity), Schwarzschild is the first to introduce the correct Lagrangian formalism of the electromagnetic field [5] as

[math]\displaystyle{ S = (1/2) \int (H^2-E^2) dV + \int \rho(\phi - \vec{A}\vec{u}) dV }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{E},\vec{H} }[/math] are the electric and magnetic field, [math]\displaystyle{ \vec{A} }[/math] is the vector potential and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] is the electric potential.

He also introduced a field free variational formulation of electrodynamics (also known as "action at distance" or "direct interparticle action") based only on the world line of particles as [6]

[math]\displaystyle{ S=\sum_{i}m_{i}\int_{C_{i}}ds_{i}+\frac{1}{2}\sum_{i,j}\iint_{C_{i},C_{j}}q_{i}q_{j}\delta\left(\left\Vert P_{i}P_{j}\right\Vert \right)d\mathbf{s}_{i}d\mathbf{s}_{j} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ C_\alpha }[/math] are the world lines of the particle, [math]\displaystyle{ d\mathbf{s}_{\alpha} }[/math] the (vectorial) arc element along the world line. Two points on two world lines contribute to the Lagrangian (are coupled) only if they are a zero Minkowskian distance (connected by a light ray), hence the term [math]\displaystyle{ \delta\left(\left\Vert P_{i}P_{j}\right\Vert \right) }[/math]. The idea was further developed by Tetrode [7] and Fokker [8] in the 1920s and Wheeler and Feynman in the 1940s [9] and constitutes an alternative/equivalent formulation of electrodynamics.

3.3. Relativity

Einstein himself was pleasantly surprised to learn that the field equations admitted exact solutions, because of their prima facie complexity, and because he himself had only produced an approximate solution. Einstein's approximate solution was given in his famous 1915 article on the advance of the perihelion of Mercury. There, Einstein used rectangular coordinates to approximate the gravitational field around a spherically symmetric, non-rotating, non-charged mass. Schwarzschild, in contrast, chose a more elegant "polar-like" coordinate system and was able to produce an exact solution which he first set down in a letter to Einstein of 22 December 1915, written while Schwarzschild was serving in the war stationed on the Russian front. Schwarzschild concluded the letter by writing: "As you see, the war treated me kindly enough, in spite of the heavy gunfire, to allow me to get away from it all and take this walk in the land of your ideas."[10] In 1916, Einstein wrote to Schwarzschild on this result:

I have read your paper with the utmost interest. I had not expected that one could formulate the exact solution of the problem in such a simple way. I liked very much your mathematical treatment of the subject. Next Thursday I shall present the work to the Academy with a few words of explanation.—Albert Einstein, [4]

Schwarzschild's second paper, which gives what is now known as the "Inner Schwarzschild solution" (in German: "innere Schwarzschild-Lösung"), is valid within a sphere of homogeneous and isotropic distributed molecules within a shell of radius r=R. It is applicable to solids; incompressible fluids; the sun and stars viewed as a quasi-isotropic heated gas; and any homogeneous and isotropic distributed gas.

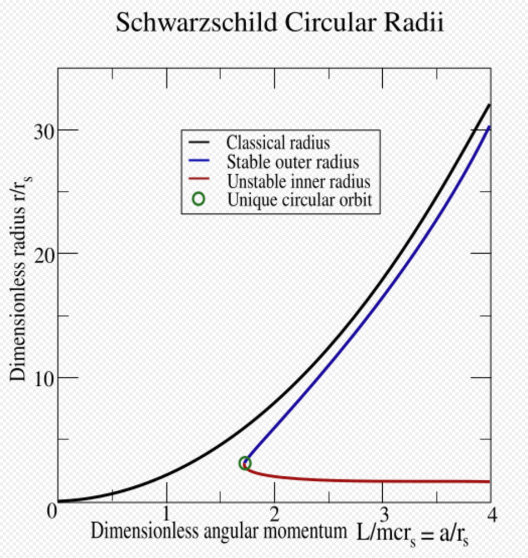

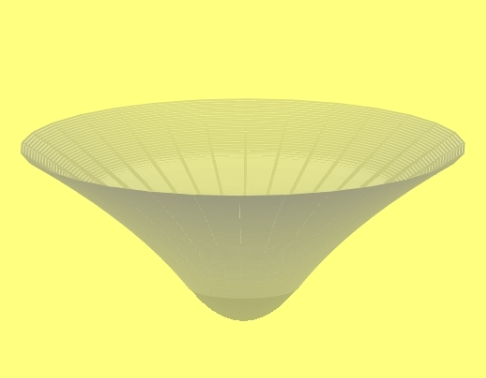

Schwarzschild's first (spherically symmetric) solution does not contain a coordinate singularity on a surface that is now named after him. In Schwarzschild coordinates, this singularity lies on the sphere of points at a particular radius, called the Schwarzschild radius:

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_{s} = \frac{2GM}{c^{2}} }[/math]

where G is the gravitational constant, M is the mass of the central body, and c is the speed of light in a vacuum.[11] In cases where the radius of the central body is less than the Schwarzschild radius, [math]\displaystyle{ R_{s} }[/math] represents the radius within which all massive bodies, and even photons, must inevitably fall into the central body (ignoring quantum tunnelling effects near the boundary). When the mass density of this central body exceeds a particular limit, it triggers a gravitational collapse which, if it occurs with spherical symmetry, produces what is known as a Schwarzschild black hole. This occurs, for example, when the mass of a neutron star exceeds the Tolman-Oppenheimer-Volkoff limit (about three solar masses).

4. Cultural References

Karl Schwarzschild appears as a character in the science fiction short story "Schwarzschild Radius" (1987) by Connie Willis.

Schwarzschild's Cat is a comic on XKCD.com comparing the size and cuteness of cats.

5. Works

- Relativity

- Über das Gravitationsfeld eines Massenpunktes nach der Einstein’schen Theorie. Reimer, Berlin 1916, S. 189 ff. (Sitzungsberichte der Königlich-Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; 1916)

- Über das Gravitationsfeld einer Kugel aus inkompressibler Flüssigkeit. Reimer, Berlin 1916, S. 424-434 (Sitzungsberichte der Königlich-Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; 1916)

- Other papers

- Untersuchungen zur geometrischen Optik I. Einleitung in die Fehlertheorie optischer Instrumente auf Grund des Eikonalbegriffs, 1906, Abhandlungen der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Band 4, Nummero 1, S. 1-31

- Untersuchungen zur geometrischen Optik II. Theorie der Spiegelteleskope, 1906, Abhandlungen der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Band 4, Nummero 2, S. 1-28

- Untersuchungen zur geometrischen Optik III. Über die astrophotographischen Objektive, 1906, Abhandlungen der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Band 4, Nummero 3, S. 1-54

- Über Differenzformeln zur Durchrechnung optischer Systeme, 1907, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 551-570

- Aktinometrie der Sterne der B. D. bis zur Größe 7.5 in der Zone 0° bis +20° Deklination. Teil A. Unter Mitwirkung von Br. Meyermann, A. Kohlschütter und O. Birck, 1910, Abhandlungen der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften in Göttingen, Band 6, Numero 6, S. 1-117

- Über das Gleichgewicht der Sonnenatmosphäre, 1906, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 41-53

- Die Beugung und Polarisation des Lichts durch einen Spalt. I., 1902, Mathematische Annalen, Band 55, S. 177-247

- Zur Elektrodynamik. I. Zwei Formen des Princips der Action in der Elektronentheorie, 1903, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 126-131

- Zur Elektrodynamik. II. Die elementare elektrodynamische Kraft, 1903, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 132-141

- Zur Elektrodynamik. III. Ueber die Bewegung des Elektrons, 1903, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 245-278

- Ueber die Eigenbewegungen der Fixsterne, 1907, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 614-632

- Ueber die Bestimmung von Vertex und Apex nach der Ellipsoidhypothese aus einer geringeren Anzahl beobachteter Eigenbewegungen, 1908, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 191-200

- K. Schwarzschild, E. Kron: Ueber die Helligkeitsverteilung im Schweif des Halley´schen Kometen, 1911, Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, S. 197-208

- Die naturwissenschaftlichen Ergebnisse und Ziele der neueren Mechanik., 1904, Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung, Band 13, S. 145-156

- Über die astronomische Ausbildung der Lehramtskandidaten., 1907, Jahresbericht der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung, Band 16, S. 519-522

- English translations

- On the Gravitational Field of a Point-Mass, According to Einstein's Theory, The Abraham Zelmanov Journal, 2008, Volume 1, P. 10-19

- On the Gravitational Field of a Sphere of Incompressible Liquid, According to Einstein's Theory, The Abraham Zelmanov Journal, 2008, Volume 1, P. 20-32

- On the Permissible Numerical Value of the Curvature of Space, The Abraham Zelmanov Journal, Volume 1, 2008, pp. 64-73

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biography:Karl_Schwarzschild

References

- "Crater Schwarzschild". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program. https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Feature/5389

- Sadri Hassani Mathematical Physics: A Modern Introduction to Its Foundations Retrieved 2012-05-27 https://books.google.com/books?id=BCMLOp6DyFIC&pg=PA919&lpg=PA919&dq=Karl+Schwarzschild+Jewish+primary+school&source=bl&ots=fYSafLsRth&sig=-lQzMooeKWWRomBiNMMfGJ_ohHY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=vo7CT76DGJOv8QOp7MzxCg&sqi=2&ved=0CF4Q6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=Karl%20Schwarzschild%20Jewish%20primary%20school&f=false

- Hertzsprung, Ejnar (1917). "Karl Schwarzschild". Astrophysical Journal 45: 285. doi:10.1086/142329. Bibcode: 1917ApJ....45..285H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F142329

- Eisenstaedt, “The Early Interpretation of the Schwarzschild Solution,” in D. Howard and J. Stachel (eds), Einstein and the History of General Relativity: Einstein Studies, Vol. 1, pp. 213-234. Boston: Birkhauser, 1989.

- K. Schwarzschild, Nachr. ges. Wiss. Gottingen (1903) 125

- K. Schwarzschild, Nachr. ges. Wiss. Gottingen (1903) 128,132

- H. Tetrode, Zeitschrift für Physik 10:137, 1922

- A. D. Fokker, Zeitschrift für Physik 58:386, 1929

- Wheeler & Feynman, Rev. Mod. Phys. 21:425 (1949)

- Letter from K Schwarzschild to A Einstein dated 22 December 1915, in "The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein", vol.8a, doc.#169, (Transcript of Schwarzschild's letter to Einstein of 22 Dec. 1915) . http://www.gsjournal.net/old/eeuro/vankov.pdf

- Landau 1975.