The elaboration likelihood model (ELM) of persuasion is a dual process theory describing the change of attitudes. The ELM was developed by Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo in 1980. The model aims to explain different ways of processing stimuli, why they are used, and their outcomes on attitude change. The ELM proposes two major routes to persuasion: the central route and the peripheral route.

- dual process theory

- persuasion

- model

1. Origin

Elaboration likelihood model is a general theory of attitude change. According to the theory's developers Richard E. Petty and John T. Cacioppo, they intended to provide a general "framework for organizing, categorizing, and understanding the basic processes underlying the effectiveness of persuasive communications".[1]

The study of attitudes and persuasion began as the central focus of social psychology, featured in the work of psychologists Gordon Allport (1935) and Edward Alsworth Ross (1908). Allport described attitudes as "the most distinctive and indispensable concept in contemporary social psychology".[2] Considerable research was devoted to the study of attitudes and persuasion from the 1930s through the late 1970s. These studies embarked on various relevant issues regarding attitudes and persuasion, such as the consistency between attitudes and behaviors[3][4] and the processes underlying attitude/behavior correspondence.[5] However, Petty and Cacioppo noticed a major problem facing attitude and persuasion researchers to the effect that there was minimal agreement regarding "if, when, and how the traditional source, message, recipient, and channel variables affected attitude change".[6] Noticing this problem, Petty and Cacioppo developed the elaboration likelihood model as their attempt to account for the differential persistence of communication-induced attitude change. Petty and Cacioppo suggested that different empirical findings and theories on attitude persistence could be viewed as stressing one of two routes to persuasion which they presented in their elaboration likelihood model.

2. Routes

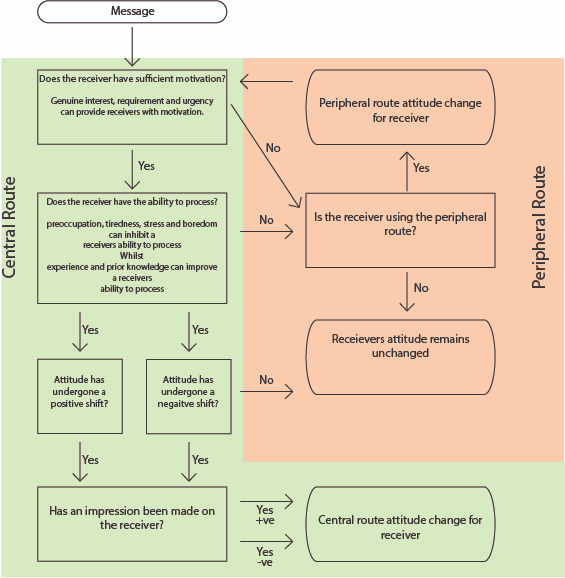

The elaboration likelihood model proposes two distinct routes for information processing: a central route and a peripheral route. The ELM holds that there are numerous specific processes of change on the "elaboration continuum" ranging from low to high. When the operation processes at the low end of the continuum determine attitudes, persuasion follows the peripheral route. When the operation processes at the high end of the continuum determine attitudes, persuasion follows the central route.[7]

2.1. Central Route

The central route is used when the message recipient has the motivation as well as the ability to think about the message and its topic. When people process information centrally, the cognitive responses, or elaborations, will be much more relevant to the information, whereas when processing peripherally, the individual may rely on heuristics and other rules of thumb when elaborating on a message. Being at the high end of the elaboration continuum, people assess object-relevant information in relation to schemas that they already possess, and arrive at a reasoned attitude that is supported by information.[7] It is important to consider two types of factors that influence how and how much one will elaborate on a persuasive message. The first are the factors that influence our motivation to elaborate, and the second are the factors that influence our ability to elaborate. Motivation to process the message may be determined by a personal interest in the subject of the message,[8] or individual factors like the need for cognition. However, if the message recipient has a strong, negative attitude toward the position proposed by the message, a boomerang effect (an opposite effect) is likely to occur. That is, they will resist the message, and may move away from the proposed position.[9] Two advantages of the central route are that attitude changes tend to last longer and are more predictive of behavior than the changes from the peripheral route.[10] Overall, as people’s motivation and ability to process the message and develop elaborations decreases, the peripheral cues present in the situation become more important in their processing of the message.

2.2. Peripheral Route

The peripheral route is used when the message recipient has little or no interest in the subject and/or has a lesser ability to process the message. Being at the low end of the elaboration continuum, recipients do not examine the information as thoroughly.[7] With the peripheral route, they are more likely to rely on general impressions (e.g. "this feels right/good"), early parts of the message, their own mood, positive and negative cues of the persuasion context, etc. Because people are "cognitive misers," looking to reduce mental effort, they often use the peripheral route and thus rely on heuristics (mental shortcuts) when processing information. When an individual is not motivated to centrally process an issue because they lack interest in it, or if the individual does not have the cognitive ability to centrally process the issue, then these heuristics can be quite persuasive. Robert Cialdini's Principles of Social Influence (1984), which include commitment, social proof, scarcity, reciprocation, authority, as well as liking the person who is persuading you, are some examples of frequently used heuristics. In addition, credibility can also be used as a heuristic in peripheral thinking because when a speaker is seen as having a higher credibility, then the listener may be more likely to believe the message. Credibility is a low-effort and somewhat reliable way to give us an answer of what to decide and/or believe without having to put in much work to think it through.

If these peripheral influences go completely unnoticed, the message recipient is likely to maintain their previous attitude towards the message. Otherwise, the individual will temporarily change his attitude towards it. This attitude change can be long-lasting, although durable change is less likely to occur than it is with the central route.[9][11]

3. Determinants of Route

The two most influential factors that affect which processing route an individual uses are motivation (the desire to process the message; see Petty and Cacioppo, 1979) and ability (the capability for critical evaluation; see Petty, Wells and Brock, 1976). The extent of motivation is in turn affected by attitude and personal relevance. Individuals' ability for elaboration is affected by distractions, their cognitive busyness (the extent to which their cognitive processes are engaged by multiple tasks[12]), and their overall knowledge.

3.1. Motivation

Attitudes towards a message can affect motivation. Drawing from cognitive dissonance theory, when people are presented with new information (a message) that conflicts with existing beliefs, ideas, or values, they will be motivated to eliminate the dissonance, in order to remain at peace with their own thoughts.[13] For instance, people who want to believe that they will be academically successful may recall more of their past academic successes than their failures. They may also use their world knowledge to construct new theories about how their particular personality traits may predispose them to academic success (Kunda, 1987). If they succeed in accessing and constructing appropriate beliefs, they may feel justified in concluding that they will be academically successful, not realizing that they also possess knowledge that could be used to support the opposite conclusion.[13]

Personal relevance can also affect an individual's degree of motivation. For instance, undergraduate students were told of a new exam policy that would take effect either one or ten years later. The proposal of the new exam policy was either supported by strong or weak arguments. Those students who were going to personally be affected by this change would think more about the issue than those students who were not going to be personally affected.[7]

An additional factor that affects degree of motivation is an individual's need for cognition. Individuals who take greater pleasure in thinking than others tend to engage in more effortful thinking because of its intrinsic enjoyment for them, regardless of the importance of the issue to them or the need to be correct.[7]

3.2. Ability

Ability includes the availability of cognitive resources (for instance, the absence of time pressures or distractions) and the relevant knowledge needed to examine arguments. Distractions (for instance, noise in a library where a person is trying to read a journal article) can decrease a person's ability to process a message. Cognitive busyness, which can also serve as a distraction, limits the cognitive resources otherwise available for the task at hand (assessing a message). Another factor of ability is familiarity with the relevant subject. Though they might not be distracted nor cognitively busy, their insufficiency in knowledge can hinder people's engagement in deep thinking.

3.3. Opportunity

Some psychologists lump opportunity in with Ability as it primarily relates to the time available to the individual to make a decision. The popular train of thought today is that this is a category of its own. [14]

4. Elements

4.1. Core Ideas

There are four core ideas to the ELM.[7]

- The ELM argues that when a person encounters some form of communication, they can process this communication with varying levels of thought (elaboration), ranging from a low degree of thought (low elaboration) to a high degree of thought (high elaboration).

- The ELM predicts that there are a variety of psychological processes of change that operate to varying degrees as a function of a person's level of elaboration. On the lower end of the continuum are the processes that require relatively little thought, including classical conditioning and mere exposure. On the higher end of the continuum are processes that require relatively more thought, including expectancy-value and cognitive response processes. When lower elaboration processes predominate, a person is said to be using the peripheral route, which is contrasted with the central route, involving the operation of predominantly high elaboration processes.

- The ELM predicts that the degree of thought used in a persuasion context determines how consequential the resultant attitude becomes. Attitudes formed via high-thought, central-route processes will tend to persist over time, resist persuasion, and be influential in guiding other judgments and behaviors to a greater extent that attitudes formed through low-thought, peripheral-route processes.

- The ELM also predicts that any given variable can have multiple roles in persuasion, including acting as a cue to judgment or as an influence on the direction of thought about a message. The ELM holds that the specific role by which a variable operates is determined by the extent of elaboration.

4.2. Assumptions

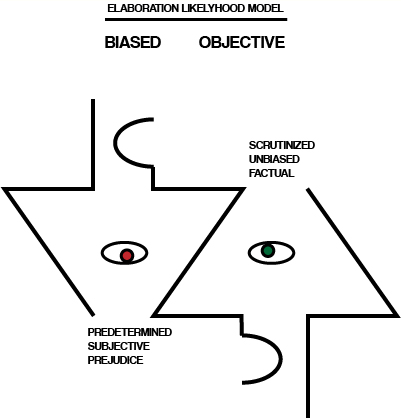

One of the main assumptions of the ELM is that the attitudes formed through the central route rather than the peripheral route are stronger and more difficult to change.[15] This means that when the central route is taken (involving high-elaboration thought in which all information is being carefully analyzed), the attitudes formed become more stable and less susceptible to counter-persuasion, whereas when the peripheral route is taken (involving low-elaboration thought based on heuristics and shortcuts to establish an attitude) short-term attitude change is more likely to occur.

4.3. Variables

A variable is essentially anything that can increase or decrease the persuasiveness of a message. Motivation (desire to process the message), ability (capability for critical evaluation), attractiveness, mood and expertise are just a few examples of variables that can influence persuasiveness. Variables also have different roles, for example, they may have a positive effect as a cue, but a negative effect if it ends up decreasing thought about a strong message.

Under high elaboration, a given variable (e.g., expertise) can serve as an argument (e.g., "If Einstein agrees with the theory of relativity, then this is a strong reason for me to as well") or a biasing factor (e.g., "If an expert agrees with this position it is probably good, so let me see who else agrees with this conclusion"), at the expense of contradicting information.[16] Under low-elaboration conditions, a variable may act as a peripheral cue (e.g., the belief that "experts are always right"). While this is similar to the Einstein example above, this is a shortcut which (unlike the Einstein example) does not require thought. Under moderate elaboration, a variable may direct the extent of information processing (e.g., "If an expert agrees with this position, I should really listen to what (s)he has to say").

Recent adaptations of the ELM[16] have added a role for variables: to affect the extent to which a person trusts their thoughts in response to a message (self-validation role).[7] A person may think, "If an expert presented this information, it is probably correct, and thus I can trust that my reactions to it are informative with respect to my attitude." This role, because of its metacognitive nature, only occurs in high-elaboration conditions.

4.4. Consequences

For an individual intent on forming long-lasting beliefs on topics, the central route is advantageous by the fact that arguments are scrutinized intensely and that information is unlikely to be overlooked. However, this route uses a considerable amount of energy, time, and mental effort.

It is not worthwhile to exert considerable mental effort to achieve correctness in all situations and people do not always have the requisite knowledge, time, or opportunity to thoughtfully assess the merits of a proposal.[7] For those, the use of the peripheral route excels at saving energy, time, and mental effort. This is particularly advantageous in situations in which one must make a decision within a small time constraint. On the other hand, the peripheral route is prone to errors in judgment, at least in attributing reasons for behaviors.[17]

5. Applications

Researchers have applied the elaboration likelihood model to many fields, including advertising, marketing, consumer behavior and health care, just to name a few.

5.1. In Advertising and Marketing

The elaboration likelihood model can be applied to advertising and marketing. In 1983, Petty, Cacioppo and Schumann conducted a study to examine source effects in advertising.[18] It was a product advertisement about a new disposable razor. The authors purposefully made one group of subjects highly involved with the product, by telling them the product would be test marketed soon in the local area and by the end of the experiment they would be given a chance to get a disposable razor. Whereas, the authors made another group of subjects have low involvement with the product by telling them that the product would be test marketed in a distant city and by the end of the experiment they would have the chance to get a toothpaste. In addition to varying involvement, the authors also varied source and message characteristics by showing a group of the subjects ads featuring popular athletes, whereas showing other subjects ads featuring average citizens; showing some subjects ads with strong arguments and others ads with weak arguments. This experiment shows that when the elaboration likelihood was low, featuring famous athletes in the advertisement would lead to more favorable product attitudes, regardless of the strength of the product attributes presented. Whereas when elaboration likelihood was high, only the argument strength would manipulate affected attitudes.[18][19]

It is widely acknowledged that effects of ads are not only limited to the information contained in the ad alone but are also a function of the different appeals used in the ads (like use celebrities or non-celebrities as endorsers).[20] In a study conducted by Rollins and Bhutada in 2013, ELM theory was the framework used to understand and evaluate the underlying mechanisms describing the relationships between endorser type, disease state involvement and consumer response to direct-to-consumer advertisements (DTCA). The finding showed while endorser type did not significantly affect consumer attitudes, behavioral intentions and information search behavior; level of disease state involvement, though, did. More highly involved consumers had more positive attitudes, behavioral intentions and greater information search behavior.[20]

5.2. In Healthcare

Recent research has been conducted to apply the ELM to the healthcare field. In 2009, Angst and Agarwal published a research article, "Adoption of Electronic Health Records in the Presence of Privacy Concerns: the Elaboration Likelihood Model and Individual Persuasion".[21] This research studies electronic health records (EHRs), (an individual's) concern for information privacy (CFIP) and the elaboration likelihood model (ELM). The two researchers aimed to investigate the question, "Can individuals be persuaded to change their attitudes and opt-in behavioral intentions toward EHRs, and allow their medical information to be digitized even in the presence of significant privacy concerns?"[22]

Since the ELM model provides an understanding how to influence attitudes, the said model could be leveraged to alter perceptions and attitudes regarding adoption and adaptation of change.

Findings of the research included:

- "Issue involvement and argument framing interact to influence attitude change, and that concern for information privacy further moderates the effects of these variables."

- "Likelihood of adoption is driven by concern for information privacy and attitude."

- "An individual's CFIP interacts with argument framing and issue involvement to affect attitudes toward EHR use and CFIP directly influence opt-in behavioral intentions."

- "Even people have high concerns for privacy, their attitudes can be positively altered with appropriate message framing."

5.3. In E-Commerce

Chen and Lee conducted a study about online shopping persuasion by applying the elaboration likelihood model back to 2008. In this study, how online shopping influences consumers' beliefs and perceived values on attitude and approach behavior were examined. "Twenty cosmetics and 20 hotel websites were selected for participants to randomly link to and read, and the students were then asked to fill in a 48-item questionnaire via the internet. It was found that when consumers have higher levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness, central route website contents would be more favorable for eliciting utilitarian shopping value; whereas when consumers have higher levels of emotional stability, openness, and extraversion, peripheral route website contents would be more critical in facilitating experiential and hedonic shopping value", Chen explained.[23]

In 2009, another study about the effects of consumer skepticism on online shopping was conducted by Sher and Lee.[24] Data on young customers' attitudes about a product were acquired through an online experiment with 278 college students, and two findings emerged after analysis. First, highly skeptical consumers tend to stick with their original impression than been influenced by other factors (Central Route); which means, they are biased against certain types of information and indifferent to the message quality. Second, consumers with low skepticism tend to adopt the peripheral route in forming attitude; that is, they are more persuaded by online review quantity. Lee indicated, "these findings contribute to the ELM research literature by considering a potentially important personality factor in the ELM framework".[24]

Other studies applied ELM in e-commerce and internet related fields are listed below for your additional references:

- How does web personalization affect users attitudes and behaviors online?[25]

- An eye-tracking study of online shopping to understand how customers use ELM in their e-commerce experience.[26]

- Using an elaboration likelihood approach to better understand the persuasiveness of website privacy assurance cues for online consumers.[27]

- Multichannel Retailing's use of central and peripheral routes through Internet and cross-channel platforms.[28]

- Using ELM and Signalling Theory to analyze Internet recruitment.[29]

5.4. In Media

In order to reduce youth smoking by developing improved methods to communicate with higher risk youth, Flynn and his colleagues conducted a study in 2013, exploring the potential of smoking prevention messages on TV based on the ELM.[30] "Structured evaluations of 12 smoking prevention messages based on three strategies derived from the ELM were conducted in classroom settings among a diverse sample of non-smoking middle school students in three states. Students categorized as likely to have higher involvement in a decision to initiate cigarette smoking, are reported relatively high ratings on a cognitive processing indicator for messages focused on factual arguments about negative consequences of smoking than for messages with fewer or no direct arguments. Message appeal ratings did not show greater preference for this message type among higher involved versus lower involved students. Ratings from students reporting lower academic achievement suggested difficulty processing factual information presented in these messages. The ELM may provides a useful strategy for reaching adolescents at risk for smoking initiation, but particular attention should be focused on lower academic achievers to ensure that messages are appropriate for them."[30]

Another research directed by Boyce and Kuijer was focusing on media body ideal images triggers food intake among restrained eaters based on ELM.[31] Their hypotheses were based on restraint theory and the ELM. From the research, they found participants' attention (advertent/inadvertent) toward the images was manipulated. Although restrained eaters' weight satisfaction was not significantly affected by either media exposure condition, advertent (but not inadvertent) media exposure triggered restrained eaters' eating. These results suggest that teaching restrained eaters how to pay less attention to media body ideal images might be an effective strategy in media–literary interventions.[31]

5.5. In Politics

Hans-Joachim Mosler applied ELM to study if and how a minority can persuade the majority to change its opinion.[32] The study used Agent-based social simulation. There were 5 agents. 3 (or 4) of whom held a neutral opinion on some abstract topic, while the other 2 (or 1) held a different opinion. In addition, there were differences between the agents regarding their argument quality and peripheral cues. The simulation was done in rounds. In each round, one of the agents had an opportunity to influence the other agents. The level of influence was determined by either the argument strength (if the central route was taken) or the peripheral cues (if the peripheral route was taken). After 20 rounds of persuasion, the distance between the majority's original opinion to its new opinion was studied. It was found that, the peripheral cues of the minority were more important than the argument quality. I.e, a minority with strong arguments but negative cues (e.g., different skin-color or bad reputation) did not succeed in convincing the majority, while a minority with weak arguments and positive cues (e.g., appearance or reputation) did succeed. The results depend also on the level of personal relevance – how much the topic is important to the majority and to the minority.

In Mental Health Counseling

Counseling and Stigma

One of the most common reasons why an individual does not attend counseling is because they are worried about the falling into a stigma (being considered crazy, or having serious “issues”).[33] This stigma—which was prevalent 30 years ago, still exists today.[34] Fortunately, an implementation of the ELM can help increase the positive perceptions of counseling amongst the undergraduate student population. Students that repeatedly watched a video that explained the function and positive outcomes of mental health counseling demonstrated a significant and lasting change in their perception to counseling. Students who watched the video once or not at all maintained a relatively negative view towards counseling.[35] Thus, repeated exposure towards the positive elements of counseling lead towards a greater elaboration and implementation of the central route to combat negative social stigma of counseling. Most negative intuitions exist within the realm of the peripheral route, and therefore to work against stigmas the general public needs to engage their central route of processing.

Counselor Credibility

The more credible a counselor is perceived as, the more likely that counseling clients are to perceive the counselor’s advice as impactful. However, counselor credibility is strongly mediated by the degree to which the client understands the information conveyed by the counselor.[36] Therefore, it is extremely important that counseling clients feel that they understand their counselor. The use of metaphor is helpful for this. Metaphors require a deeper level of elaboration, thereby engaging the central route of processing. Kendall (2010)[37] suggests using metaphor in counseling as a valid method towards helping clients understand the message/psychological knowledge conveyed by the client. When the client hears a metaphor that resonates with them, they are far more likely to trust and build positive rapport with the counselor.[38]

6. Methodological Considerations

In designing a test for the aforementioned model, it is necessary to determine the quality of an argument, i.e., whether it is viewed as strong or weak. If the argument is not seen as strong, then the results of persuasion will be inconsistent. A strong argument is defined by Petty and Cacioppo as "one containing arguments such that when subjects are instructed to think about the message, the thoughts they generate are fundamentally favorable."[39] An argument that is universally viewed as weak will elicit unfavorable results, especially if the subject considers it under high elaboration, thus being the central route. Test arguments must be rated by ease of understanding, complexity and familiarity. To study either route of the elaboration likelihood model, the arguments must be designed for consistent results.[40] Also, when assessing persuasion of an argument, the influence of peripheral cues needs to be taken into consideration as cues can influence attitude even in the absence of argument processing.[41] The extent or direction of message processing also needs to be taken into consideration when assessing persuasion, as variables can influence or bias thought by enabling or inhibiting the generation of a particular kind of thought in regard to the argument.[41] "While the ELM theory continues to be widely cited and taught as one of the major cornerstones of persuasion, questions are raised concerning its relevance and validity in 21st century communication contexts."[42]

7. Critiques of the Theory

Some researchers have been criticized for misinterpreting the ELM. One such instance is Kruglanski and Thompson, who write that the processing of central or peripheral routes is determined by the type of information that affects message persuasion. For example, message variables are only influential when the central route is used and information like source variables is only influential when the peripheral route is used. In fact, the ELM does not make statements about types of information being related to routes. Rather, the key to the ELM is how any type of information will be used depending on central or peripheral routes, regardless of what that information is.[11] For example, the central route may permit source variables to influence preference for certain language usage in the message (e.g. "beautiful") or validate a related product (e.g. cosmetics), while the peripheral route may only lead individuals to associate the "goodness" of source variables with the message. Theoretically, all of these could occur simultaneously. Thus, the distinction between central and peripheral routes is not the type of information being processed as those types can be applied to both routes, but rather how that information is processed and ultimately whether processing information in one way or the other will result in different attitudes.

A second instance of misinterpretation is that processing of the central route solely involves thinking about the message content and not thoughts about the issue.[43] Petty and Cacioppo (1981) stated "If the issue is very important to the person, but the person doesn't understand the arguments being presented in the message, or if no arguments are actually presented, then elaboration of arguments cannot occur.…Nevertheless, the person may still be able to think about the issue."[44] Therefore, issue-relevant thinking is still a part of the central route and is necessary for one to think about the message content.

Lastly, a third instance of misinterpretation by Kruglanski and Thompson is the disregard for the quantitative dimension presented by the ELM and more focus on the qualitative dimension. This quantitative dimension is the peripheral route involves low-elaboration persuasion that is quantitatively different from the central route that involves high elaboration. With this difference the ELM also explains that low-elaboration persuasion processes are qualitatively different as well.[43] It is seen as incorrect if the ELM focuses on a quantitative explanation over a qualitative one; however one of the ELM's key points is that elaboration can range from high to low which is not incorrect as data from experiments conducted by Petty (1997)[45] as well as Petty and Wegener (1999)[46] suggest that persuasion findings can be explained by a quantitative dimension without ever needing a qualitative one.[43]

8. Alternative Models

- Social judgment theory – emphasizes the distance in opinions, and whether it is in the "acceptance latitude" or "rejection latitude" or in the intermediate zone.

- Social impact theory - emphasizes the number, strength and immediacy of the people trying to influence a person to change its mind.

- Heuristic-systematic model

- Extended transportation-imagery model

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Finance:Elaboration_likelihood_model

References

- Petty, Richard E; Cacioppo, John T (1986). "The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion". Advances in Experimental Social Psychology: 125. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60214-2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0065-2601%2808%2960214-2

- Allport, Gordon (1935). "Attitudes". A Handbook of Social Psychology: 789–844.

- Ajzen, Icek; Fishbein, Martin (1977). "Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research.". Psychological Bulletin, American Psychological Association 84 (5): 888–918. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0033-2909.84.5.888

- Fazio, Russell H; Zanna, Mark P (1981). "Direct experience and attitude-behavior consistency". Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 14: 161–202. doi:10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60372-x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0065-2601%2808%2960372-x

- Sherman, Steve J; Fazio, Russell H; Herr, Paul M (1983). "On the consequences of priming: Assimilation and contrast effects". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 19 (4): 323–340. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(83)90026-4. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0022-1031%2883%2990026-4

- Petty, Richard E; Cacioppo, John T (1986). "The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion". Advances in Experimental Social Psychology: 124–125.

- Kruglanski, Arie W.; Van Lange, Paul A.M. (2012). Handbook of theories of social psychology. London, England: Sage. pp. 224–245.

- Morris, J. D.; Singh, A. J.; Woo, C.. "Elaboration likelihood model: A missing intrinsic emotional implication". Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 14: 79–98. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jt.5740171. https://dx.doi.org/10.1057%2Fpalgrave.jt.5740171

- Griffin, E. (2012). In addition, there are different variables that a persuader can use to affect an individual’s ability to process a message (commonly used factors are the presence or absence of distractions, background knowledge of the topic, and the comprehensibility of the message or how easy it is to understand) that can enhance or reduce the amount of critical thinking that one would use to create elaborations from the message being presented. A First Look at Communication Theory, 8th ed. McGraw-Hill: New York, 205-207.

- McNeill, Brian W. (1989). "Reconceptualizing social influence in counseling: The Elaboration Likelihood Model.". Journal of Counseling Psychology 36: 24–33. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.36.1.24. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com.gate.lib.buffalo.edu/ehost/detail/detail?sid=431af8ef-0d10-4e05-afd2-2c517701e4ba%40sessionmgr111&vid=0&hid=103&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#db=pdh&AN=1989-19793-001.

- Chaiken & Trope (Eds.)(1999)

- "Social Cognition". http://webspace.ship.edu/ambart/Psy_220/SocCog_outline.htm.

- Kunda, Ziva (1990). "The Case for Motivated Reasoning". Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 480–498. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. PMID 2270237. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0033-2909.108.3.480

- http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/6813/volumes/v15/NA-15

- Petty R. and Cacioppo J. "Communication and persuasion: central and peripheral routes to attitude change." Springer-Verlag, New York.

- Petty, R. (2002). "Thought confidence as a determinant of persuasion: the self validation hypothesis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 82: 722–741. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.722. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0022-3514.82.5.722

- Gilbert, Daniel T.; Pelham, Brett W.; Krull, Douglas S. (1988). "On Cognitive Busyness: When Person Perceivers Meet Persons Perceived". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54 (5): 733–740. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.5.733. https://dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F0022-3514.54.5.733

- Petty, Richard E; Cacioppo, John T; Schumann, David (1983). "Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement". Journal of Consumer Research 10: 135–146. doi:10.1086/208954. https://dx.doi.org/10.1086%2F208954

- Petty, Richard E; Cacioppo, John T (1984). "Source factors and the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion". Advances in Consumer Research: 668–672.

- Rollins, B.; Bhutada, N. (2014). "Impact Of Celebrity Endorsements In Disease-Specific Direct-To-Consumer (DTC) Advertisements: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Approach". International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing 8 (2): 164–177. doi:10.1108/ijphm-05-2013-0024. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108%2Fijphm-05-2013-0024

- Angst, Corey; Agarwal, Ritu (2009). "Adoption of electronic health records in the presence of privacy concerns: the elaboration likelihood model and individual persuasion". MIS Quarterly 33 (2): 339–370.

- Angst, Corey; Agarwal, Ritu (2009). "Adoption of electronic health records in the presence of privacy concerns: the elaboration likelihood model and individual persuasion". MIS Quarterly 33 (2): 339.

- Chen, S.; Lee, K. (2008). "The Role Of Personality Traits And Perceived Values In Persuasion: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective On Online Shopping". Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal 36 (10): 1379–1400. doi:10.2224/sbp.2008.36.10.1379. https://dx.doi.org/10.2224%2Fsbp.2008.36.10.1379

- Sher, P. J.; Lee, S. (2009). "Consumer Skepticism And Online Reviews: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective". Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal 37 (1): 137–143. doi:10.2224/sbp.2009.37.1.137. https://dx.doi.org/10.2224%2Fsbp.2009.37.1.137

- Ho, S.; Bodoff, D. (2014). "The Effects Of Web Personalization On User Attitude And Behavior: An Integration Of The Elaboration Likelihood Model And Consumer Search Theory". MIS Quarterly 38 (2): 497–A10.

- Yang, S (2015). "An Eye-Tracking Study Of The Elaboration Likelihood Model In Online Shopping". Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 14 (4): 233–240. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2014.11.007. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.elerap.2014.11.007

- Benjamin Lowry, Paul; Moody, Gregory D.; Vance, Anthony; Jensen, Matthew L.; Jenkins, Jeffrey L.; Wells, Taylor (2012). "Using an elaboration likelihood approach to better understand the persuasiveness of website privacy assurance cues for online consumers". Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology (JASIST) 63 (4): 755–766. doi:10.1002/asi.21705. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fasi.21705

- Bezes, C (2015). "Identifying Central And Peripheral Dimensions Of Store And Website Image: Applying The Elaboration Likelihood Model To Multichannel Retailing". Journal of Applied Business Research 31 (4): 1453.

- Gregory, C.; Meade, A.; Thompson, L. (2013). "Understanding Internet Recruitment Via Signaling Theory And The Elaboration Likelihood Model". Computers in Human Behavior 29 (5): 1949–1959. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.04.013. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.chb.2013.04.013

- Flynn, B. S.; Worden, J. K.; Bunn, J. Y.; Connolly, S. W.; Dorwaldt, A. L. (2011). "Evaluation Of Smoking Prevention Television Messages Based On The Elaboration Likelihood Model". Health Education Research 26 (6): 976–987. doi:10.1093/her/cyr082. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3219883

- Boyce, J.; Kuijer, R. (2014). "Focusing On Media Body Ideal Images Triggers Food Intake Among Restrained Eaters: A Test Of Restraint Theory And The Elaboration Likelihood Model". Eating Behaviors 15 (2): 262–270. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.03.003. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.eatbeh.2014.03.003

- Hans-Joachim Mosler (2006). "Better Be Convincing or Better Be Stylish? a Theory Based Multi-Agent Simulation to Explain Minority Influence in Groups Via Arguments or Via Peripheral Cues". Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation. http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/9/3/4.html.

- Nelson, G. D., & Barbaro, M. B. (1985). Fighting the stigma: A unique approach to marketing mental health. Health Marketing Quarterly, 2, 89–101.

- Topkaya, N., Vogel, D. L., & Brenner, R. E. (2017). Examination of the stigmas toward help seeking among Turkish college students. Journal Of Counseling & Development, 95(2), 213-225. doi:10.1002/jcad.12133

- Kaplan, S. A., Vogel, D. L., Gentile, D. A., & Wade, N. G. (2012). Increasing positive perceptions of counseling: The importance of repeated exposures. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(3), 409-442. doi:10.1177/0011000011414211

- Hu, B. (2013). Examining elaboration likelihood model in counseling context. Asian Journal Of Counselling, 20(1-2), 33-58.

- Kendall, W. A. (2010). Examining the persuasive effect of metaphor use in psychotherapy: An experimental test of contributing factors. Dissertation Abstracts International, 71, 3377.

- Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2014). The role of mentalizing and epistemic trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychotherapy, 51(3), 372-380. doi:10.1037/a0036505

- Griffin E. A First Look at Communication Theory, 8th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, p366 - 377.

- Berkowitz L. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol 19. Academic press, Orlando 1986 p132 - 134. Print.

- Petty, Richard E. (1986). Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. Springer New York.

- Kitchen, P.; Kerr, G.; Schultz, D.; McColl, R.; Pals, H. (2014). "The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Review, Critique And Research Agenda". European Journal of Marketing 48 (11/12): 2033–2050. doi:10.1108/EJM-12-2011-0776. https://dx.doi.org/10.1108%2FEJM-12-2011-0776

- Richard E. Petty; S. Christian Wheeler; George Y. Bizer (1999). Is There One Persuasion Process or More? Lumping Versus Splitting in Attitude Change Theories. http://www.psy.ohio-state.edu/petty/PDF%20Files/1999-PI-Petty,Wheeler,Bizer.pdf.

- Petty, R. E.; Cacioppo, J. T. (1981). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary approaches.

- Petty, Richard E. (1997). The Evolution of Theory and Research in Social Psychology: From Single to Multiple Effect and Process Models of Persuasion. http://www.psy.ohio-state.edu/petty/documents/1997EVOLUTIONOFTHEORYPetty.pdf.

- Petty, R.E.; Wegener, D.T. (1999). The Elaboration Likelihood Model: Current Status and Controversies. http://www.psy.ohio-state.edu/petty/PDF%20Files/1999-DUAL%20PROCESS-Petty,Wegener.pdf.