The East African lion is a Panthera leo melanochaita population in East Africa. During the 20th century, lion populations in this part of Africa became fragmented and declined in several range countries due to loss of habitat and prey base, poaching and killing of lions to protect livestock and human life. In 2005, a Lion Conservation Strategy was developed for East and Southern Africa. Today, lion populations are stable only in large protected area complexes. The scientific name P. l. melanochaita was proposed for the Cape lion in 1842 that was eradicated in the mid-19th century. P. l. melanochaita differs genetically from P. leo leo; the two subspecies probably diverged at least 50,000 years ago.

- lion

- lions

- conservation

1. Characteristics

The lion's fur varies in colour from light buff to dark brown. It has rounded ears and a black tail tuft. Average head-to-body length of male lions is 2.47–2.84 m (8.1–9.3 ft) with a weight of 148.2–190.9 kg (327–421 lb). Females are smaller and less heavy.[1] The Cape lion had a black mane extending beyond the shoulders and under the belly.[2] Until the late 20th century, mane colour and size was thought to be a distinct subspecific characteristic.[3] In 2002, research in Serengeti National Park revealed that mane darkens with age; its colour and size are influenced by environmental factors like temperature and climate, but also by individual testosterone production, sexual maturity and genetic precondition. Mane length apparently signals fighting success in male–male relationships.[4]

2. Taxonomy

Charles Hamilton Smith described the type specimen for Panthera leo melanochaita in 1842 using the scientific name Felis (Leo) melanochaitus.[2] In the 19th and 20th centuries, several naturalists described zoological specimens from East Africa and proposed subspecies, including:

- Felis leo somaliensis (Noack 1891), based on two lion specimens from Somalia[5]

- Felis leo massaicus (Neumann 1900), based on two lions killed near Kibaya and the Gurui River in Kenya[6]

- Felis leo sabakiensis (Lönnberg 1910), based on two lions from the environs of Mount Kilimanjaro[7]

- Felis leo bleyenberghi (Lönnberg 1914), a male lion from the Katanga Province of Belgian Congo[8]

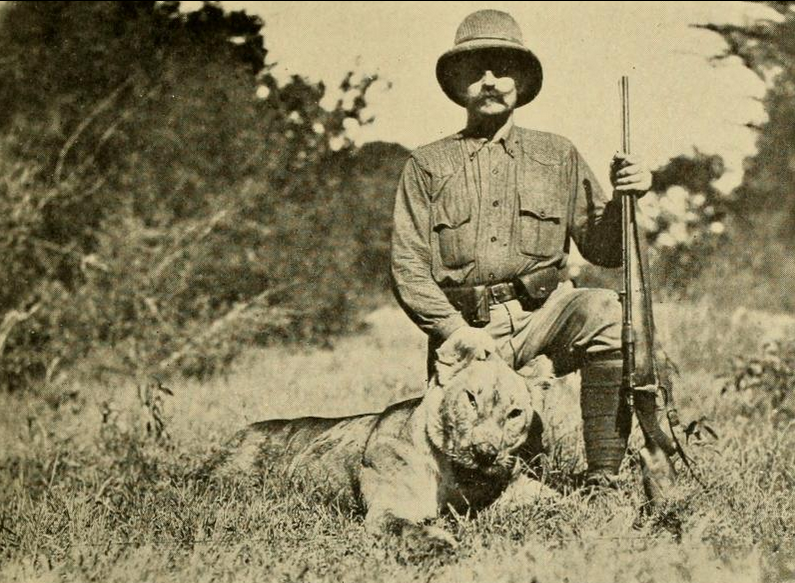

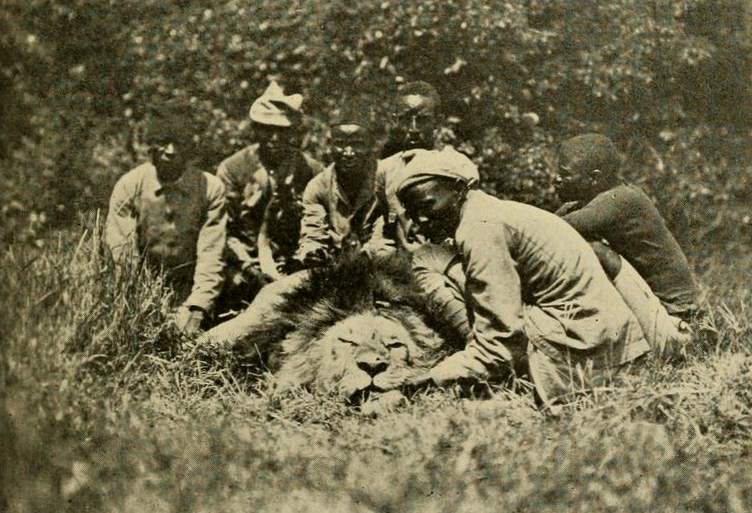

- Felis leo roosevelti (Heller 1914), a lion from the Ethiopian Highlands presented to Theodore Roosevelt[9]

- Felis leo nyanzae (Heller 1914), a lion skin from Kampala, Uganda[9]

- Leo leo hollisteri (Joel Asaph Allen 1924), a male lion from the area of Lime Springs, Sotik on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria[10]

- Panthera leo webbensies Ludwig Zukowsky 1964, two lions from Somalia, one in the Natural History Museum, Vienna that originated in Webi Shabeelle, the other kept in a German zoo that had been imported from the hinterland of Mogadishu.[11]

Dispute over the validity of these purported subspecies continued among naturalists and curators of natural history museums until the early 21st century.[3][12][13][14]

In 2017, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group revised lion taxonomy based on results of phylogeographic research on lion samples. Two lion subspecies are now recognised:[15]

- P. l. melanochaita is understood as comprising lion populations in the contemporary Southern and East African range countries;

- P. l. leo comprises lion populations in North, West and Central Africa and Asia.

2.1. Genetic Research

Since the beginning of the 21st century, several phylogenetic studies were conducted to aid clarifying the taxonomic status of lion samples kept in museums and collected in the wild. Scientists analysed between 32 and 480 lion samples from up to 22 countries. They all agree that the species lion comprises two evolutionary groups, one in East and Southern Africa, and the other in the northern and eastern parts of its historical range; these groups diverged about 50,000 years ago. They assume that tropical rainforest and the East African Rift constituted major barriers between the two groups.[16][17][18][19][20][21]

Among six samples from captive lions that originated in Ethiopia, five samples clustered with samples from East Africa, but one clustered with samples from the Sahel.[19] For a subsequent study, also eight wild lion samples from the Ethiopian Highlands were included in the analysis. Of these, three clustered with the Central African lion and five with samples from East Africa. Scientists therefore assume that the Ethiopian Highlands east and west of the Rift Valley is a genetic admixture zone between both phylogeographic groups.[21]

3. Distribution and Habitat

In East Africa, lions inhabit a wide variety of habitats including savanna and arid landscapes, open grasslands and miombo woodlands.[23][24] Lion populations declined in:

- Somalia since the early 20th century.[25] Intensive poaching since the 1980s and civil unrest in El Buur District posed a threat to lion persistence.[26][27]

- Uganda to near extinction due to poaching since the 1970s following civil unrest.[28][29]

- Democratic Republic of Congo in the 1990s during the first and second civil wars.[29]

- Kenya in the 1990s due to poisoning of lions and poaching of lion prey species.[27] At least 108 lions were killed between 2001 and 2006 in the Amboseli-Tsavo East-Tsavo West protected area network.[30]

- Rwanda and Tanzania due to killing of lions during the Rwandan Civil War and ensuing refugee crisis in the 1990s.[27]

Contemporary lion distribution and habitat quality in East Africa was assessed in 2005, and Lion Conservation Units (LCU) mapped.[31] Between 2002 and 2012, educated guesses for size of populations in the East African LCUs ranged from 20,485 to 18,308 individuals.[27][32]

| Range countries | Lion Conservation Units | Area in km2 |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Republic of Congo | Massif D'itombwe, Luama | 8,441[31] |

| Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda | Queen Elizabeth-Virunga | 5,583[33] |

| Uganda | Toro-Semulik, Lake Mburo, Murchison Falls | 4,800[34] |

| Somalia | Arboweerow-Alafuuto | 24,527[31] |

| Somalia, Kenya | Bushbush-Arawale | 22,540[31] |

| Kenya | Laikipia-Samburu, Meru and Nairobi National Parks | 43,706[32] |

| Kenya, Tanzania | Serengeti-Mara and Tsavo-Mkomazi | 75,068[22] |

| Tanzania | Dar-Biharamulo, Ruaha-Rungwa, Mpanga-Kipengere, Tarangire, Wami Mbiki-Saadani, Selous | 384,489[22] |

The LCUs Serengeti-Mara, Tsavo-Mkomazi, Ruaha-Rungwa and Selous are currently considered lion strongholds in East Africa. They host more than 500 individuals each, and the population trend is stable.[32]

4. Ecology and Behaviour

In the Serengeti National Park, lion prides have been monitored since 1966.[35] Between 1966 and 1972, two observed lion prides comprised between seven and 10 females each that had litters once in 23 months on average.[36] Litters contained two to three cubs. Females suckled cubs of other females, when their cubs were of similar age. Of 87 cubs born until 1970, only 12 reached the age of two years. Cubs died due to starvation in months when large prey was not available, following take-over of prides by new males, or of unknown causes.[37] Male lion coalitions were more successful in taking over prides than single males. Coalitions of six males stayed longer with a pride than smaller male groups.[38] Between 1974 and 2012, 471 coalitions comprising 796 male lions entered a study area of 2,000 km2 (770 sq mi). Of these, 35 nomadic coalitions included male lions that were born in the area but had left and returned after about two years of absence. Coalitions became resident at between 3.5 and 7.3 years of age.[39]

5. Threats

In Somalia's Lower Shabeelle area, hunters kill female lions and collect cubs to trade them in wildlife markets, where they fetch at between US$ 500 and 600 per cub. In southern Somalia, people also keep lion cubs for export.[40]

6. Conservation

All lion populations in Africa have been included in CITES Appendix II since 1975.[41] Because of the negative impact of trophy hunting, it was proposed in 2004 to list them all in CITES Appendix I to reduce exports of lion trophies and implement a stricter permission process.[42]

In 2006, a Lion Conservation Strategy for East and Southern Africa was developed in cooperation between IUCN regional offices and several wildlife conservation organisations. The strategy envisages to maintain sufficient habitat, ensure a sufficient wild prey base, make lion-human coexistence sustainable and reduce factors that lead to further fragmentation of populations.[31]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:East_African_lion

References

- Guggisberg, C.A.W. (1975). "Lion Panthera leo (Linnaeus 1758)". Wild Cats of the World. London: David and Charles. pp. 138–179. ISBN 0715371142.

- Smith, C.H. (1842). "Black maned lion Leo melanochaitus". in Jardine, W.. The Naturalist's Library. Vol. 15 Mammalia. London: Chatto and Windus. p. Plate X, 177. https://archive.org/stream/naturalistslibra15jardrich#page/176/mode/2up.

- Hemmer, H. (1974). "Untersuchungen zur Stammesgeschichte der Pantherkatzen (Pantherinae) Teil 3. Zur Artgeschichte des Löwen Panthera (Panthera) leo (Linnaeus, 1758)". Veröffentlichungen der Zoologischen Staatssammlung 17: 167–280. https://archive.org/stream/verfentlichungen171974zool#page/178/mode/2up.

- West, P.M.; Packer, C. (2002). "Sexual Selection, Temperature, and the Lion's Mane". Science 297 (5585): 1339–1943. doi:10.1126/science.1073257. PMID 12193785. Bibcode: 2002Sci...297.1339W. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1073257

- Noack, T. (1891). "Felis leo". Jahrbuch der Hamburgischen Wissenschaftlichen Anstalten 9 (1): 120.

- Neumann, O. (1900). "Die von mir in den Jahren 1892–95 in Ost- und Central-Afrika, speciell in den Massai-Ländern und den Ländern am Victoria Nyansa gesammelten und beobachteten Säugethiere". Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abtheilung für Systematik, Geographie und Biologie der Thiere 13 (VI): 529–562. https://archive.org/stream/zoologischejahrb13jena#page/550/mode/2up.

- Lönnberg, E. (1910). "Mammals". in Sjöstedt, Y.. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Schwedischen Zoologischen Expedition nach dem Kilimandjaro, dem Meru und den umgebenden Massaisteppen Deutsch-Ostafrikas 1905–1906. Volume 1. Uppsala: Königlich Schwedische Akademie der Wissenschaften. https://archive.org/stream/wissenschaftlich01sj#page/n133/mode/2up.

- Lönnberg, E. (1914). "New and rare mammals from Congo". Revue de Zoologie Africaine (3): 273–278. https://archive.org/stream/revuezoologiquea03brux#page/272/mode/2up.

- Heller, E. (1914). "New races of carnivores and baboons from equatorial Africa and Abyssinia". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections 61 (19): 1–12. https://archive.org/stream/smithsonianmisce611914smit#page/n579/mode/2up.

- Allen, J. A. (1924). "Carnivora Collected By The American Museum Congo Expedition". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 47: 73–281. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinamerican47ameruoft#page/223/mode/2up.

- Zukowsky, L. (1964). "Eine neue Löwenrasse als weiterer Beleg für die Verzwergung der Wirbeltierfauna des afrikanischen Osthorns". Milu, Wissenschaftliche und Kulturelle Mitteilungen aus dem Tierpark Berlin (1): 269–273.

- Allen, G. M. (1939). "A Checklist of African Mammals". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard College 83: 1–763. https://archive.org/stream/bulletinofmuseum83harv#page/242/mode/2up.

- Mazak, V. (1975). "Notes on the Black-maned Lion of the Cape, Panthera leo melanochaita (Ch. H. Smith, 1842) and a Revised List of the Preserved Specimens". Verhandelingen Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (64): 1–44.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Panthera leo". in Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 546. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=14000228.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V. et al. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group". Cat News (Special Issue 11): 71–73. https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/32616/A_revised_Felidae_Taxonomy_CatNews.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Barnett, R.; Yamaguchi, N.; Barnes, I.; Cooper, A. (2006). "The origin, current diversity and future conservation of the modern lion (Panthera leo)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 273 (1598): 2119–2125. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3555. PMID 16901830. PMC 1635511. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070808182526/http://www.adelaide.edu.au/acad/publications/papers/Barnett%20PRS%20lions.pdf.

- Antunes, A.; Troyer, J. L.; Roelke, M. E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Packer, C.; Winterbach, C.; Winterbach, H.; Johnson, W. E. (2008). "The Evolutionary Dynamics of the Lion Panthera leo Revealed by Host and Viral Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics 4 (11): e1000251. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000251. PMID 18989457. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2572142

- Mazák, J.H. (2010). "Geographical variation and phylogenetics of modern lions based on craniometric data". Journal of Zoology. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2010.00694.x. ISSN 09528369. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1469-7998.2010.00694.x

- Bertola, L. D.; Van Hooft, W. F.; Vrieling, K.; Uit De Weerd, D.R.; York, D. S.; Bauer, H.; Prins, H.H.T.; Funston, P.J. et al. (2011). "Genetic diversity, evolutionary history and implications for conservation of the lion (Panthera leo) in West and Central Africa". Journal of Biogeography 38 (7): 1356–1367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02500.x. http://dspace.learningnetworks.org/bitstream/1820/4311/1/2011_Bertola,Hooft,Vrieling,Weerd,York,Bauer,Prins,Haes,Iongh_GeneticDiversityEvolutionaryHistoryAndImplicationsForConservationOfTheLionInWestAndCentralAfrica.pdf.

- Dubach, J.M., Briggs, M.B., White, P.A., Ament, B.A., & Patterson, B.D. (2013). "Genetic perspectives on “Lion Conservation Units” in Eastern and Southern Africa". Conservation Genetics 14 (4): 741−755.

- Bertola, L.D.; Jongbloed, H.; Van Der Gaag, K.J.; De Knijff, P.; Yamaguchi, N.; Hooghiemstra, H.; Bauer, H.; Henschel, P. et al. (2016). "Phylogeographic patterns in Africa and High Resolution Delineation of genetic clades in the Lion (Panthera leo)". Scientific Reports 6: 30807. doi:10.1038/srep30807. PMID 27488946. PMC 4973251. Bibcode: 2016NatSR...630807B. https://www.nature.com/articles/srep30807?WT.feed_name=subjects_evolution.

- Mésochina, P., Mbangwa, O., Chardonnet, P., Mosha, R., Mtui, B., Drouet, N. and Kissui, B. (2010). Conservation status of the lion (Panthera leo Linnaeus, 1758) in Tanzania. Paris: SCI Foundation, MNRT-WD, TAWISA & IGF Foundation.

- Hanby, J. P., Bygott, J. D., Packer, C. (1995). "Ecology, demography and behavior of lions in two contrasting habitats: Ngorongoro Crater and the Serengeti Plains". in Sinclair, A.R.E., Arcese, P.. Serengeti II: Dynamics, Management, and Conservation of an Ecosystem. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 315–331.

- Crosmary, W. G., Ikanda, D., Ligate, F. A., Sandini, P., Mkasanga, I., Mkuburo, L., Chardonnet, P. (2018). "Lion densities in Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania". South African Journal of Wildlife Research 48 (1): 014001.

- Funaioli, U.; Simonetta, A.M. (1966). "The Mammalian Fauna of the Somali Republic: Status and Conservation Problems". Monitore Zoologico Italiano, Supplemento 1 (1): 285–347. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03749444.1966.10736746.

- Fagotto, F. (2009). "Larger Animals of Somalia in 1984". Environmental Conservation 12 (3): 260−264. doi:10.1017/S0376892900016015. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0376892900016015

- Chardonnet, P. (2002). "Chapter II: Population Survey". Conservation of the African Lion : Contribution to a Status Survey. Paris: International Foundation for the Conservation of Wildlife, France & Conservation Force, USA. pp. 21–101. http://conservationforce.org/pdf/conservationoftheafricanlion.pdf.

- Treves, A.; Naughton-Treves, L. (1999). "Risk and opportunity for humans coexisting with large carnivores". Journal of Human Evolution 36 (3): 275–282. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0268. ISSN 00472484. https://faculty.nelson.wisc.edu/treves/pubs/1999_Risk_and_Opportunity.pdf.

- Plumptre, A.J., Kujirakwinja, D., Treves, A., Owiunji, I. and Rainer, H. (2007). "Transboundary conservation in the greater Virunga landscape: its importance for landscape species". Biological Conservation 134 (2): 279−287.

- Frank, L., Maclennan, S., Hazzah, L., Hill, T., Bonham, R. (2006). Lion Killing in the Amboseli-Tsavo Ecosystem, 2001–2006, and its Implications for Kenya's Lion Population. Nairobi: Living with Lions. http://www.livingwithlions.org/AnnualReports/2006-Lion-killing-in-Amboseli-Tsavo-ecosystem.pdf.

- IUCN Cat Specialist Group (2006). Conservation Strategy for the Lion Panthera leo in Eastern and Southern Africa. Pretoria, South Africa: IUCN.

- Riggio, J.; Jacobson, A.; Dollar, L.; Bauer, H.; Becker, M.; Dickman, A.; Funston, P.; Groom, R. et al. (2013). "The size of savannah Africa: a lion’s (Panthera leo) view". Biodiversity and Conservation 22 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10531-012-0381-4.

- Treves, A.; Plumptre, A. J.; Hunter, L.T.B.; Ziwa, J. (2009). "Identifying a potential lion Panthera leo stronghold in Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda, and Parc National des Virunga, Democratic Republic of Congo". Oryx 43 (1): 60–66. doi:10.1017/S003060530700124X. https://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS003060530700124X

- Mudumba, T., Mulondo, P., Okot, E., Nsubuga, M., Plumptre, A. (2010). National census of lions and hyaenas in Uganda. Uganda: Uganda Wildlife Authority.

- Schaller, G. B. (1972). The Serengeti lion: A study of predator–prey relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73639-6.

- Bertram, B.C.R. (1973). "Lion population regulation". East Africa Wildlife Journal 11 (3-4): 215−225. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1973.tb00088.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1365-2028.1973.tb00088.x

- Bertram, B. (1975). "Social factors influencing reproduction in wild lions". Journal of Zoology 177: 463–482.

- Bygott, J.D., Bertram, B.C.R., Hanby, J.P. (1979). "Male lions in large coalitions gain reproductive advantages". Nature 282: 839–841.

- Borrego, N., Ozgul, A., Slotow, R. and Packer, C. (2018). "Lion population dynamics: do nomadic males matter?". Behavioral Ecology 29 (3): 660–666. doi:10.1093/beheco/ary018. https://dx.doi.org/10.1093%2Fbeheco%2Fary018

- Amir, O.G. (2006). "5.2.2. Lion". Wildlife trade in Somalia. Report to the IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group. Darmstadt, Germany. pp. 14−15. http://www.wmenews.com/newsletters/File/Volume-1/Issue-4/support_art/Wildlife_Trade_in_Somalia_20061.pdf#14.

- Template:IUCN

- Nowell, K. (2004). "The Cat Specialist Group at CITES 2004". Cat News 41: 29.