Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is one of eight known herpesviruses with the potential to infect humans. EBV latency, and more particularly the proteins expressed during this phase of the viral cycle, is heavily implicated in EBV-mediated oncogenesis.

- EBV

- epithelial cancer

- nasopharyngeal cancer

1. Introduction

Epstein–Barr Virus (EBV) is a highly prevalent gamma herpesvirus that has infected more than 90% of the population worldwide [1]. In addition to being the causative agent of infectious mononucleosis, EBV was the first human oncogenic virus to be discovered and has been linked to numerous malignancies, including various epithelial and mesenchymal cancers and lymphomas [2]. EBV-associated cancers are known to affect both immune-competent hosts and immunocompromised patients [3]. Globally, it is believed that EBV is responsible for approximately 1.5% of all human cancers [4]. EBV transmission primarily occurs through saliva, with increased levels of viral DNA being found in salivary secretions after the initial infection [5]. Other methods of transmission include blood transfusion and allograft transplantation [6]. Socioeconomics influence the age at which primary EBV infection occurs, as demonstrated by the cohort study performed by Gares et al. in the UK. This study found that children who slept in overcrowded homes (OR = 1.14 (1.10–1.31)) were found to have a higher rate of infection with EBV by three years of age when compared to children who lived in better conditions [7].

EBV is a member of the Herpesviridae family; more specifically, the Gammaherpesvirinae subfamily. It is also known as Human herpesvirus 4 (HHV4). Its genome is composed of linear double-stranded DNA that is approximately 170 kb in length and includes approximately 85 genes [8]. Traditionally, EBV strains have been classified into type 1 and type 2 (also known as types A and B, respectively) primarily based on the sequence of their EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA), specifically EBNA2 and EBNA3A/B/C latency genes [9]. Type 1 EBV strains are more prevalent worldwide, with type 2 being more prevalent in Alaska, Papua New Guinea and Central Africa [10]. The main phenotypic difference in vitro between these two strains is that type 1 EBV transforms human B lymphocytes into lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCL) more efficiently than type 2 [9]. In a retrospective study conducted by Monteiro et al., EBV2 was shown to have a longer clinical course than EBV1, with an average duration of 17.6 days of fever (range of 1–90 days), while EBV1 had an average range of 14.8 days (range of 1–30 days) [11]. Interestingly, this study also noted that the levels of hepatic enzymes were significantly higher, on average, in EBV1-infected patients aged 14 years and older when compared to those infected with EBV2 or coinfected with EBV1 and EBV2 [11].

B lymphocytes are the primary targets of EBV infection due to their expression of complement receptor type 2 (CR2), also known as the complement C3d receptor or CD21 [12]. EBV first infects B cells through the binding of the viral envelope protein gp350 with CR2 [13]. The ensuing interaction of viral envelope proteins gp42, gH/gL and gB with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II protein on the B cell surface results in the fusion of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane and allows for EBV to enter the cell [14]. Another target of EBV is epithelial cells. While EBV enters B cells by fusion with an endocytic membrane after endocytosis, EBV enters epithelial cells by fusion at the plasma membrane [15]. The glycoproteins used by EBV to enter epithelial cells depend on both the cell type and the expression of CR2. EBV uses gp350 for attachment to CR2-positive epithelial cells [16]. For CR2-negative epithelial cells, EBV can use the multi-spanning transmembrane envelope protein BMRF-2 to bind to integrin αvβ1, or it can use gH/gL to bind to integrin αvβ5, αvβ6 or αvβ8 [17][18][19].

After the initial infection, EBV establishes and maintains an episome in the nucleus of the host cell. It predominantly establishes latency that cannot be eradicated in B cells [20]. In a recent study performed by Wang et al., EBV episomes were found to specifically target host “super enhancers” that have a strong affinity for the binding of transcriptional coactivators in order to facilitate greater EBV gene expression and cancer proliferation [21]. Similar to other herpesviruses, the EBV life cycle alternates between latent and lytic states [22]. In immunocompetent individuals, EBV is typically found in a latent, asymptomatic state. Disturbances of the host immune system can stimulate viral reactivation [23]. These includes stressors such as oxidative stress, co-infection with viruses such as CMV or HPV, and immunosuppressive or chemotherapeutic treatments and stem cell transplantation. A comprehensive review of factors that can stimulate EBV reactivation was discussed by Sausen et al. in a separate review [23].

EBV is associated with a host of diseases, including but not limited to Sjögren’s syndrome [24], systemic lupus erythematosus [24], rheumatoid arthritis [24], hairy leukoplakia [25], Alzheimer’s [26], Parkinson’s [26], and acute cerebellar ataxia [26]. Additionally, a recent study of greater than 10 million young adults demonstrated that EBV infection resulted in a 32-fold increased risk of developing multiple sclerosis (MS) [27]. In this study, neurofilament light chain, a marker of neuroaxonal degeneration, increased following EBV infection, indicating that EBV may be a driving factor in the pathogenesis of MS [27]. This is reminiscent of virus-induced animal models (e.g., Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus model) of demyelinating diseases including MS. [28]

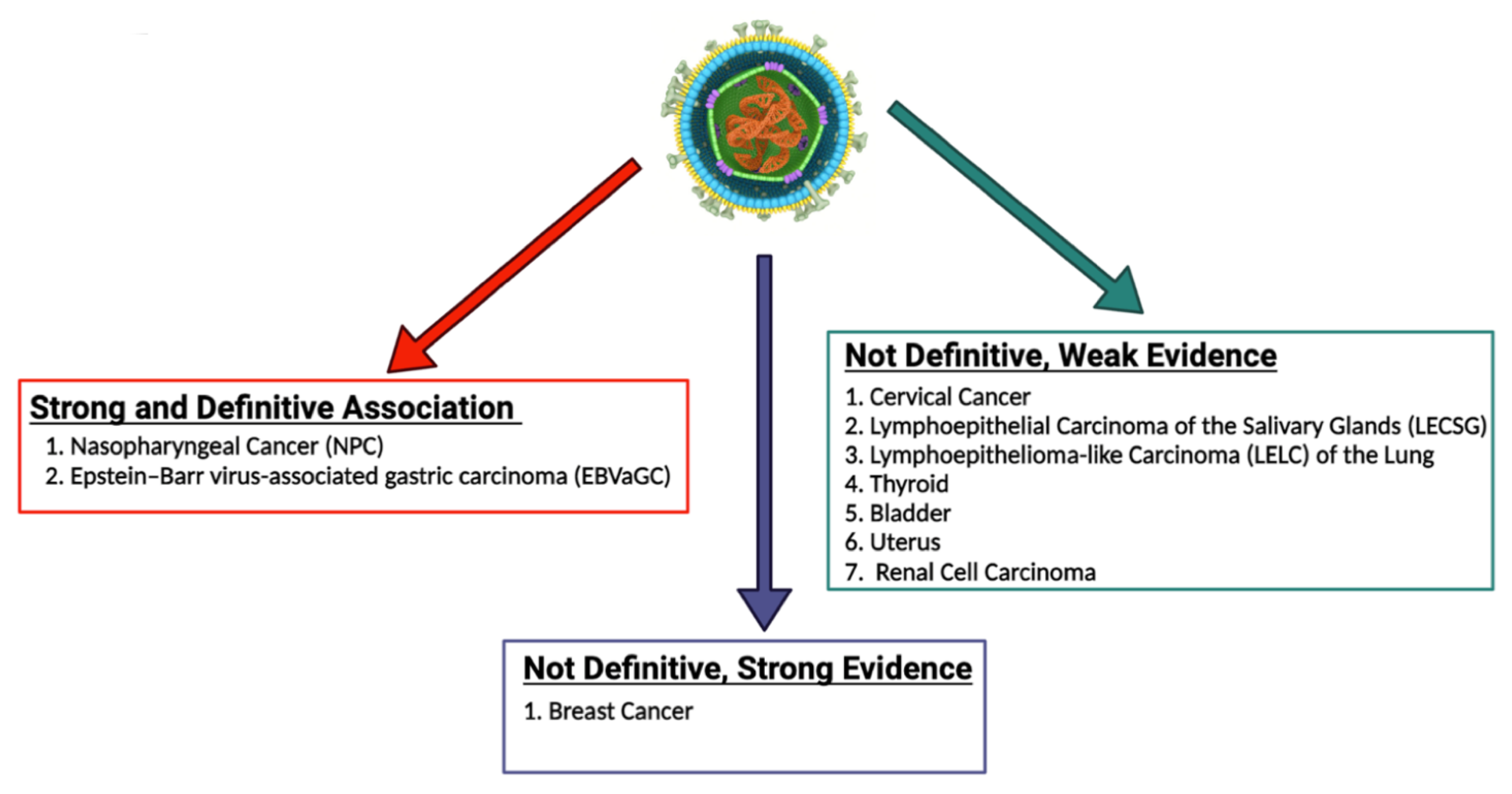

Since Epstein and Barr first discovered EBV in Burkitt lymphoma (BL) cells in 1964, a myriad of other malignancies have been both strongly and causally linked to EBV [29]. These malignancies can be categorized as those which are lymphoproliferative and those which are epithelial in nature [30]. In addition to BL, lymphoproliferative diseases associated with EBV include Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL), and extranodal T/NK cell lymphoma, as well as the rarer plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL) and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) [31]. Epithelial malignancies with a well-known association with EBV include gastric cancer (GC) and nasopharyngeal cancer (NPC) [32]. Additionally, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that there is a strong statistical relationship between EBV infection and the risk of developing breast cancer [33]. Other epithelial malignancies with a weaker correlation to EBV include lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands (LECSG), lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung (LELC), renal cell carcinoma, thyroid cancer, cervical cancer, bladder cancer and leiomyomas/leiomyosarcomas in immunocompromised patients [34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]. Figure 1 below lists these epithelial malignancies associated with EBV. It is important to note that EBV infection does not lead to malignant transformation of normal epithelial cells, raising uncertainty about the causal role of EBV in the oncogenesis of these cancers [47].

Figure 1. EBV-associated epithelial malignancies. EBV is associated with numerous malignancies with varying degrees of evidence. There is numerous evidence linking EBV to both nasopharyngeal carcinoma and gastric carcinoma. With regard to breast cancer, some studies provide strong evidence that EBV plays a role in the pathogenesis of breast cancer, while some studies call for more definitive evidence to be published. EBV has been less definitively associated with numerous other epithelial malignancies, including cervical cancer, lymphoepithelial carcinoma of the salivary glands, lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma of the lung, thyroid cancer, bladder cancer, uterine cancer, and renal cell carcinoma [34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46]. The role of EBV in the pathogenesis of these cancers should be further explored and definitively established.

2. EBV Latency

EBV latency, and more particularly the proteins expressed during this phase of the viral cycle, is heavily implicated in EBV-mediated oncogenesis [48][49]. The proteins ultimately expressed during latent infection varies based on the latency type. In type I latency, infected cells express EBNA1, EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER), and BamHI fragment A rightward transcripts (BART) transcripts. In type IIa latency, infected cells express everything seen in type I latency as well as latent membrane proteins (LMP) 1 and 2. Type IIb latency resembles type IIa latency, but features the expression of EBNA2, EBNA3, and EBNA-leader protein (LP) instead of LMP 1 and 2. Type III latency includes the expression of EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, and 3C, EBNA-LP, LMP 1 and 2, EBER 1 and 2, and the microRNAs (miRNA) miR-BHRF1 and miR-BART3. A type 0 latency has also been described in which only EBERs are expressed.

EBV-related cancers are associated with specific latency patterns [50]. For example, EBVaGC is associated with latency type I or II [51] while nasopharyngeal cancer is associated with type II latency [52]. Among the EBV-associated hematologic malignancies, Burkitt lymphoma is typically characterized by type I latency [50], diffuse large B cell lymphoma most frequently expresses a type II latency (although it is less often associated with type III latency) [50], and both classic [53] and nodular lymphocyte-predominant (NLPHL) [54] Hodgkin lymphoma typically express type II latency. Notably, there is some evidence to suggest that certain cancers can express non-canonical latency patterns ([55][56]).

More details about these patterns can be found elsewhere [57][58]. Table 1 summarizes EBV latency expression patterns and Table 2 reviews which patterns of latency are associated with which malignancy.

Table 1. Patterns of EBV protein expression during latency.

| Latency 0 | Latency I | Latency IIa | Latency IIb | Latency III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBNA1 | − | + | + | + | + |

| EBNA2 | − | − | − | + | + |

| EBNA3 | − | − | − | + | + |

| EBNA-LP | − | − | − | + | + |

| LMP1 | − | − | + | − | + |

| LMP2 | − | − | + | − | + |

| BARTs | − | + | + | + | + |

| EBERs | + | + | + | + | + |

Table 1 summarizes the EBV protein expression seen in each type of latency. “+” indicates the protein is expressed, while “−” indicates that the protein is not expressed.

Table 2. EBV latency patterns and associated malignancies.

| Latency Type | Associated Malignancies |

|---|---|

| Latency I | EBVaGC, Burkitt lymphoma |

| Latency II | EBVaGC, NPC, DLCBL, classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma, NLPHL |

| Latency III | DLBCL |

Table 2 provides an overview of which malignancies are associated with which patterns of EBV latent gene expression.

The ability of EBV to transform B cells has long been known [59][60], and latent gene products have been implicated in the transformation process [60][61][62]. B cell transformation results in significant differences in B cell gene organization and expression. For example, Hernando et al. found that B cells transformed by EBV displayed altered methylation markings and endonuclease activity when compared to non-transformed cells [63]. These changes were noted to affect thousands of genes and were not seen in B cells whose proliferation was induced with CD40/IL4 [63]. Of particular note, EBV infection leads to hypermethylation, and therefore decreased expression, of tumor suppressor genes when compared to naïve B cells [64]. An RNA sequencing analysis of gene expression in primary human resting B lymphocytes infected with the EBV strain B95.8 revealed changes in gene expression in nearly 3700 genes, including changes in 94% of the genes required for lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) growth and survival [65].

EBV Latent Proteins and Oncogenesis

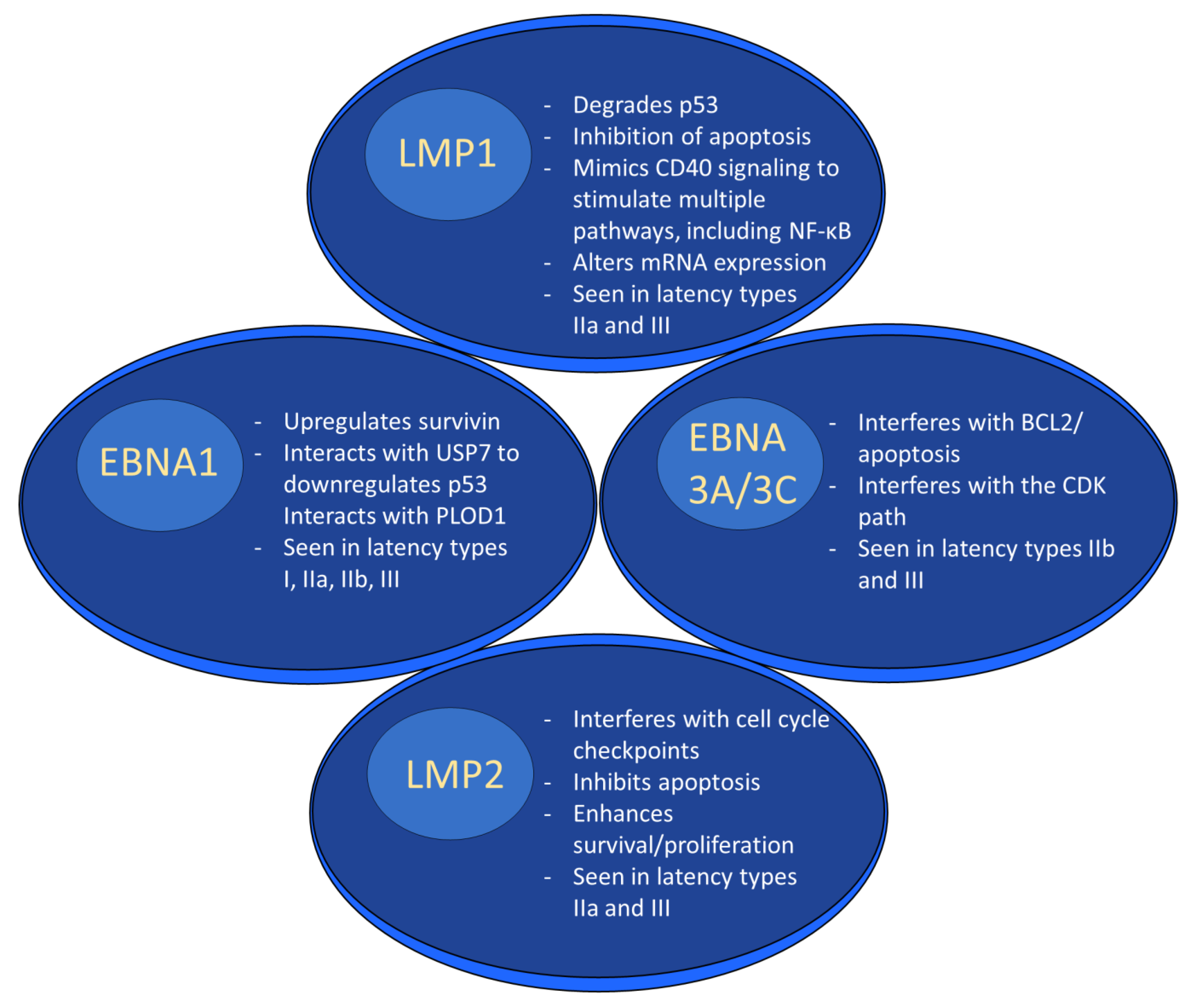

Gene products expressed during EBV latency play key roles in oncogenesis. LMP1 is a highly oncogenic protein that mimics CD40 signaling, leading to stimulation of multiple pathways [66], including nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) [66][67]. It exerts its oncogenic properties through multiple mechanisms in a variety of tumor types. For example, LMP1-mediated p53 degradation and subsequent enhanced tumorigenesis [68] has been noted in several cancer lines [69]. LMP1 also activates PI3K/AKT, and the combination of PI3K/AKT and NF-κB activation has been shown to inhibit apoptosis in lymphoma patients [70][71]. In nasopharyngeal cancer cells, LMP1 alters miRNA expression, which may promote tumor formation [48]. In addition to its role as a B cell receptor mimic, LMP2A impairs apoptosis and cell cycle checkpoints and works synergistically with oncogenes to enhance survival and proliferation [49].

EBNA1 is another latent protein implicated in tumor formation. In B cell lymphoma, it has been shown to upregulate an anti-apoptotic protein named survivin [72][73]. In nasopharyngeal carcinoma, ENBA1 can inhibit NF-κB through inhibition of IKKα and β, which promotes development of squamous cell carcinoma by stimulating tissue hyperplasia [74]. EBNA1 interacts with ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) to decrease P53 levels [75]. In addition, it was recently shown that some EBNA1 variants, particularly those with the amino acid substitution T85A, can more easily bind the cellular protein Procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 1 (PLOD1) [76], which is associated with gastric cancer [77]. Moreover, PLOD1 overexpression carries a poorer prognosis in gastric cancer [78]. The EBNA3 family of latent genes, including EBNAs3A, 3B, and 3C, are intriguing in that they play opposing roles in oncogenesis, with EBNA3A and 3C promoting cancer formation and EBNA3B suppressing it [79]. EBNA3A and 3C interact to induce tumor formation through a variety of mechanisms, including interfering with the BCL2/apoptosis and cyclin dependent kinase (CDK) pathways [80]. As was mentioned above, EBNA3B acts as a tumor suppressor; indeed, murine infection by EBV strains lacking EBNA3B result in aggressive, immuno-evasive diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [81]. Infected cells secreted lower levels of the T cell chemoattractant CXCL10, which inhibited T cell recruitment and killing of infected cells. Notably, human B cell lymphomas were shown to have altered EBNA3B expression [81]. The role of selected EBV proteins has been summarized in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. EBV latent proteins and oncogenesis. EBV latent proteins play numerous roles in facilitating oncogenesis. For example, LMP1 degrades p53, alters mRNA expression and stimulates multiple pathways through mimicking CD40 signaling. EBNA1 upregulates survivin, downregulates p53, and interacts with PLOD1. EBNA3A/3C interferes w/BCL2/apoptosis and interferes with the CDK pathway. LMP2 interferes with the cell cycle, inhibits apoptosis, and enhances survival/proliferation.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms232214389

References

- Zanella, L.; Riquelme, I.; Buchegger, K.; Abanto, M.; Ili, C.; Brebi, P. A reliable Epstein-Barr Virus classification based on phylogenomic and population analyses. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9829.

- Lieberman, P.M. Virology. Epstein-Barr virus turns 50. Science 2014, 343, 1323–1325.

- Ko, Y.H. EBV and human cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e130.

- Farrell, P.J. Epstein-Barr Virus and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2019, 14, 29–53.

- Ikuta, K.; Satoh, Y.; Hoshikawa, Y.; Sairenji, T. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus in salivas and throat washings in healthy adults and children. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2, 115–120.

- Dunmire, S.K.; Verghese, P.S.; Balfour, H.H., Jr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 102, 84–92.

- Gares, V.; Panico, L.; Castagne, R.; Delpierre, C.; Kelly-Irving, M. The role of the early social environment on Epstein Barr virus infection: A prospective observational design using the Millennium Cohort Study. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 3405–3412.

- Rivailler, P.; Cho, Y.G.; Wang, F. Complete genomic sequence of an Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesvirus naturally infecting a new world primate: A defining point in the evolution of oncogenic lymphocryptoviruses. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 12055–12068.

- Romero-Masters, J.C.; Huebner, S.M.; Ohashi, M.; Bristol, J.A.; Benner, B.E.; Barlow, E.A.; Turk, G.L.; Nelson, S.E.; Baiu, D.C.; Van Sciver, N.; et al. B cells infected with Type 2 Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) have increased NFATc1/NFATc2 activity and enhanced lytic gene expression in comparison to Type 1 EBV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008365.

- Zimber, U.; Adldinger, H.K.; Lenoir, G.M.; Vuillaume, M.; Knebel-Doeberitz, M.V.; Laux, G.; Bornkamm, G.W. Geographical prevalence of two types of Epstein-Barr virus. Virology 1986, 154, 56–66.

- Monteiro, T.A.F.; Costa, I.B.; Costa, I.B.; Correa, T.; Coelho, B.M.R.; Silva, A.E.S.; Ramos, F.L.P.; Filho, A.J.M.; Monteiro, J.L.F.; Siqueira, J.A.M.; et al. Genotypes of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV1/EBV2) in individuals with infectious mononucleosis in the metropolitan area of Belem, Brazil, between 2005 and 2016. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 24, 322–329.

- Fingeroth, J.D.; Weis, J.J.; Tedder, T.F.; Strominger, J.L.; Biro, P.A.; Fearon, D.T. Epstein-Barr virus receptor of human B lymphocytes is the C3d receptor CR2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4510–4514.

- Young, K.A.; Herbert, A.P.; Barlow, P.N.; Holers, V.M.; Hannan, J.P. Molecular basis of the interaction between complement receptor type 2 (CR2/CD21) and Epstein-Barr virus glycoprotein gp350. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 11217–11227.

- Tsang, C.M.; Deng, W.; Yip, Y.L.; Zeng, M.S.; Lo, K.W.; Tsao, S.W. Epstein-Barr virus infection and persistence in nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Chin. J. Cancer 2014, 33, 549–555.

- Miller, N.; Hutt-Fletcher, L.M. Epstein-Barr virus enters B cells and epithelial cells by different routes. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 3409–3414.

- Nemerow, G.R.; Mold, C.; Schwend, V.K.; Tollefson, V.; Cooper, N.R. Identification of gp350 as the viral glycoprotein mediating attachment of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) to the EBV/C3d receptor of B cells: Sequence homology of gp350 and C3 complement fragment C3d. J. Virol. 1987, 61, 1416–1420.

- Loesing, J.B.; Di Fiore, S.; Ritter, K.; Fischer, R.; Kleines, M. Epstein-Barr virus BDLF2-BMRF2 complex affects cellular morphology. J. Gen. Virol. 2009, 90, 1440–1449.

- Chesnokova, L.S.; Hutt-Fletcher, L.M. Fusion of Epstein-Barr virus with epithelial cells can be triggered by alphavbeta5 in addition to alphavbeta6 and alphavbeta8, and integrin binding triggers a conformational change in glycoproteins gHgL. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 13214–13223.

- Chesnokova, L.S.; Nishimura, S.L.; Hutt-Fletcher, L.M. Fusion of epithelial cells by Epstein-Barr virus proteins is triggered by binding of viral glycoproteins gHgL to integrins alphavbeta6 or alphavbeta8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20464–20469.

- Moquin, S.A.; Thomas, S.; Whalen, S.; Warburton, A.; Fernandez, S.G.; McBride, A.A.; Pollard, K.S.; Miranda, J.L. The Epstein-Barr Virus Episome Maneuvers between Nuclear Chromatin Compartments during Reactivation. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e01413-17.

- Wang, L.; Laing, J.; Yan, B.; Zhou, H.; Ke, L.; Wang, C.; Narita, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Olson, M.R.; Afzali, B.; et al. Epstein-Barr Virus Episome Physically Interacts with Active Regions of the Host Genome in Lymphoblastoid Cells. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01390-20.

- Kempkes, B.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein-Barr virus latency: Current and future perspectives. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015, 14, 138–144.

- Sausen, D.G.; Bhutta, M.S.; Gallo, E.S.; Dahari, H.; Borenstein, R. Stress-Induced Epstein-Barr Virus Reactivation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1380.

- Houen, G.; Trier, N.H. Epstein-Barr Virus and Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 587380.

- Rathee, M.; Jain, P. Hairy Leukoplakia. In StatPearls; Statpearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022.

- Zhang, N.; Zuo, Y.; Jiang, L.; Peng, Y.; Huang, X.; Zuo, L. Epstein-Barr Virus and Neurological Diseases. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 816098.

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301.

- Zhang, J.; Lipton, H.L.; Perelson, A.S.; Dahari, H. Modeling the acute and chronic phases of Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus infection. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 4052–4059.

- Epstein, M.A.; Achong, B.G.; Barr, Y.M. Virus Particles in Cultured Lymphoblasts from Burkitt’s Lymphoma. Lancet 1964, 1, 702–703.

- Ok, C.Y.; Li, L.; Young, K.H. EBV-driven B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: From biology, classification and differential diagnosis to clinical management. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47, e132.

- Shannon-Lowe, C.; Rickinson, A.B.; Bell, A.I. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphomas. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160271.

- Lung, R.W.; Tong, J.H.; To, K.F. Emerging roles of small Epstein-Barr virus derived non-coding RNAs in epithelial malignancy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 17378–17409.

- Farahmand, M.; Monavari, S.H.; Shoja, Z.; Ghaffari, H.; Tavakoli, M.; Tavakoli, A. Epstein-Barr virus and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 2873–2885.

- Thompson, L.D.R.; Whaley, R.D. Lymphoepithelial Carcinoma of Salivary Glands. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2021, 14, 75–96.

- Yeh, Y.C.; Kao, H.L.; Lee, K.L.; Wu, M.H.; Ho, H.L.; Chou, T.Y. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Pulmonary Carcinoma: Proposing an Alternative Term and Expanding the Histologic Spectrum of Lymphoepithelioma-like Carcinoma of the Lung. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 211–219.

- Becnel, D.; Abdelghani, R.; Nanbo, A.; Avilala, J.; Kahn, J.; Li, L.; Lin, Z. Pathogenic Role of Epstein-Barr Virus in Lung Cancers. Viruses 2021, 13, 877.

- Farhadi, A.; Namdari, S.; Chong, P.P.; Geramizadeh, B.; Behzad-Behbahani, A.; Sekawi, Z.; Sharifzadeh, S. Epstein-Barr virus infection is associated with the nuclear factor-kappa B p65 signaling pathway in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Urol. 2022, 22, 17.

- Shimakage, M.; Kawahara, K.; Harada, S.; Sasagawa, T.; Shinka, T.; Oka, T. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus in renal cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2007, 18, 41–46.

- Kim, K.H.; Han, E.M.; Lee, E.S.; Park, H.S.; Kim, I.; Kim, Y.S. Epstein-Barr virus infection in sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma tissues. BJU Int. 2005, 96, 547–552.

- Moghoofei, M.; Mostafaei, S.; Nesaei, A.; Etemadi, A.; Sadri Nahand, J.; Mirzaei, H.; Rashidi, B.; Babaei, F.; Khodabandehlou, N. Epstein-Barr virus and thyroid cancer: The role of viral expressed proteins. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 3790–3799.

- Homayouni, M.; Mohammad Arabzadeh, S.A.; Nili, F.; Razi, F.; Amoli, M.M. Evaluation of the presence of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in Iranian patients with thyroid papillary carcinoma. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2017, 213, 854–856.

- de Lima, M.A.P.; Neto, P.J.N.; Lima, L.P.M.; Goncalves Junior, J.; Teixeira Junior, A.G.; Teodoro, I.P.P.; Facundo, H.T.; da Silva, C.G.L.; Lima, M.V.A. Association between Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cervical carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 2018, 148, 317–328.

- Vranic, S.; Cyprian, F.S.; Akhtar, S.; Al Moustafa, A.E. The Role of Epstein-Barr Virus in Cervical Cancer: A Brief Update. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 113.

- Gazzaniga, P.; Vercillo, R.; Gradilone, A.; Silvestri, I.; Gandini, O.; Napolitano, M.; Giuliani, L.; Fioravanti, A.; Gallucci, M.; Agliano, A.M. Prevalence of papillomavirus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus type 2 in urinary bladder cancer. J. Med. Virol. 1998, 55, 262–267.

- Abe, T.; Shinohara, N.; Tada, M.; Harabayashi, T.; Sazawa, A.; Maruyama, S.; Moriuchi, T.; Takada, K.; Nonomura, K. Infiltration of Epstein-Barr virus-harboring lymphocytes occurs in a large subset of bladder cancers. Int. J. Urol. 2008, 15, 429–434.

- McClain, K.L.; Leach, C.T.; Jenson, H.B.; Joshi, V.V.; Pollock, B.H.; Parmley, R.T.; DiCarlo, F.J.; Chadwick, E.G.; Murphy, S.B. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in young people with AIDS. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 332, 12–18.

- Young, L.S.; Yap, L.F.; Murray, P.G. Epstein-Barr virus: More than 50 years old and still providing surprises. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 789–802.

- Muller Coan, B.G.; Cesarman, E.; Acencio, M.L.; Elgui de Oliveira, D. Latent Membrane Protein 1 (LMP1) from Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Strains M81 and B95.8 Modulate miRNA Expression When Expressed in Immortalized Human Nasopharyngeal Cells. Genes 2022, 13, 353.

- Fish, K.; Comoglio, F.; Shaffer, A.L., 3rd; Ji, Y.; Pan, K.T.; Scheich, S.; Oellerich, A.; Doebele, C.; Ikeda, M.; Schaller, S.J.; et al. Rewiring of B cell receptor signaling by Epstein-Barr virus LMP2A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26318–26327.

- Marques-Piubelli, M.L.; Salas, Y.I.; Pachas, C.; Becker-Hecker, R.; Vega, F.; Miranda, R.N. Epstein-Barr virus-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders and lymphomas: A review. Pathology 2020, 52, 40–52.

- Shinozaki-Ushiku, A.; Kunita, A.; Fukayama, M. Update on Epstein-Barr virus and gastric cancer (review). Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46, 1421–1434.

- Choi, S.J.; Jung, S.W.; Huh, S.; Cho, H.; Kang, H. Phylogenetic comparison of Epstein-Barr virus genomes. J. Microbiol. 2018, 56, 525–533.

- Massini, G.; Siemer, D.; Hohaus, S. EBV in Hodgkin Lymphoma. Mediterr J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2009, 1, e2009013.

- Gerhard-Hartmann, E.; Johrens, K.; Schinagl, L.M.; Zamo, A.; Rosenwald, A.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Rosenfeldt, M. Epstein-Barr virus infection patterns in nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Histopathology 2022, 80, 1071–1080.

- Lorenzetti, M.A.; De Matteo, E.; Gass, H.; Martinez Vazquez, P.; Lara, J.; Gonzalez, P.; Preciado, M.V.; Chabay, P.A. Characterization of Epstein Barr virus latency pattern in Argentine breast carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13603.

- Granai, M.; Mundo, L.; Akarca, A.U.; Siciliano, M.C.; Rizvi, H.; Mancini, V.; Onyango, N.; Nyagol, J.; Abinya, N.O.; Maha, I.; et al. Immune landscape in Burkitt lymphoma reveals M2-macrophage polarization and correlation between PD-L1 expression and non-canonical EBV latency program. Infect. Agent Cancer 2020, 15, 28.

- Kanda, T. EBV-Encoded Latent Genes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2018, 1045, 377–394.

- Murata, T.; Sugimoto, A.; Inagaki, T.; Yanagi, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Sato, Y.; Kimura, H. Molecular Basis of Epstein-Barr Virus Latency Establishment and Lytic Reactivation. Viruses 2021, 13, 2344.

- Borrebaeck, C.A. Strategy for the production of human monoclonal antibodies using in vitro activated B cells. J. Immunol. Methods 1989, 123, 157–165.

- Cahir McFarland, E.D.; Izumi, K.M.; Mosialos, G. Epstein-barr virus transformation: Involvement of latent membrane protein 1-mediated activation of NF-kappaB. Oncogene 1999, 18, 6959–6964.

- Wang, J.; Nagy, N.; Masucci, M.G. The Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1 upregulates the cellular antioxidant defense to enable B-cell growth transformation and immortalization. Oncogene 2020, 39, 603–616.

- Szymula, A.; Palermo, R.D.; Bayoumy, A.; Groves, I.J.; Ba Abdullah, M.; Holder, B.; White, R.E. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA-LP is essential for transforming naive B cells, and facilitates recruitment of transcription factors to the viral genome. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006890.

- Hernando, H.; Islam, A.B.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Forne, I.; Ciudad, L.; Imhof, A.; Shannon-Lowe, C.; Ballestar, E. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated transformation of B cells induces global chromatin changes independent to the acquisition of proliferation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 249–263.

- Saha, A.; Jha, H.C.; Upadhyay, S.K.; Robertson, E.S. Epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes during in vitro Epstein-Barr virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E5199–E5207.

- Wang, C.; Li, D.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, S.; Liang, J.; Narita, Y.; Hou, I.; Zhong, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Xiao, H.; et al. RNA Sequencing Analyses of Gene Expression during Epstein-Barr Virus Infection of Primary B Lymphocytes. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00226-19.

- Wang, L.W.; Jiang, S.; Gewurz, B.E. Epstein-Barr Virus LMP1-Mediated Oncogenicity. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01718-16.

- Laherty, C.D.; Hu, H.M.; Opipari, A.W.; Wang, F.; Dixit, V.M. The Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene product induces A20 zinc finger protein expression by activating nuclear factor kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 24157–24160.

- Zeng, M.; Chen, Y.; Jia, X.; Liu, Y. The Anti-Apoptotic Role of EBV-LMP1 in Lymphoma Cells. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8801–8811.

- Chatterjee, K.; Das, P.; Chattopadhyay, N.R.; Mal, S.; Choudhuri, T.C. The interplay between Epstein-Bar virus (EBV) with the p53 and its homologs during EBV associated malignancies. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02624.

- Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, H.; Ma, C.; Wei, L. LMP-1 induces survivin expression to inhibit cell apoptosis through the NF-kappaB and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways in nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 2253–2260.

- Hatton, O.; Lambert, S.L.; Krams, S.M.; Martinez, O.M. Src kinase and Syk activation initiate PI3K signaling by a chimeric latent membrane protein 1 in Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)+ B cell lymphomas. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42610.

- Lu, J.; Murakami, M.; Verma, S.C.; Cai, Q.; Haldar, S.; Kaul, R.; Wasik, M.A.; Middeldorp, J.; Robertson, E.S. Epstein-Barr Virus nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) confers resistance to apoptosis in EBV-positive B-lymphoma cells through up-regulation of survivin. Virology 2011, 410, 64–75.

- Ai, M.D.; Li, L.L.; Zhao, X.R.; Wu, Y.; Gong, J.P.; Cao, Y. Regulation of survivin and CDK4 by Epstein-Barr virus encoded latent membrane protein 1 in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines. Cell Res. 2005, 15, 777–784.

- Valentine, R.; Dawson, C.W.; Hu, C.; Shah, K.M.; Owen, T.J.; Date, K.L.; Maia, S.P.; Shao, J.; Arrand, J.R.; Young, L.S.; et al. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded EBNA1 inhibits the canonical NF-kappaB pathway in carcinoma cells by inhibiting IKK phosphorylation. Mol. Cancer 2010, 9, 1.

- Saridakis, V.; Sheng, Y.; Sarkari, F.; Holowaty, M.N.; Shire, K.; Nguyen, T.; Zhang, R.G.; Liao, J.; Lee, W.; Edwards, A.M.; et al. Structure of the p53 binding domain of HAUSP/USP7 bound to Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 implications for EBV-mediated immortalization. Mol. Cell 2005, 18, 25–36.

- Shire, K.; Marcon, E.; Greenblatt, J.; Frappier, L. Characterization of a cancer-associated Epstein-Barr virus EBNA1 variant reveals a novel interaction with PLOD1 and PLOD3. Virology 2021, 562, 103–109.

- Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Chen, F. High Expression of PLOD1 Drives Tumorigenesis and Affects Clinical Outcome in Gastrointestinal Carcinoma. Genet. Test Mol. Biomark. 2018, 22, 366–373.

- Li, S.S.; Lian, Y.F.; Huang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.H.; Xiao, J. Overexpressing PLOD family genes predict poor prognosis in gastric cancer. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 121–131.

- Saha, A.; Robertson, E.S. Mechanisms of B-Cell Oncogenesis Induced by Epstein-Barr Virus. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00238-19.

- Allday, M.J.; Bazot, Q.; White, R.E. The EBNA3 Family: Two Oncoproteins and a Tumour Suppressor that Are Central to the Biology of EBV in B Cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 391, 61–117.

- White, R.E.; Ramer, P.C.; Naresh, K.N.; Meixlsperger, S.; Pinaud, L.; Rooney, C.; Savoldo, B.; Coutinho, R.; Bodor, C.; Gribben, J.; et al. EBNA3B-deficient EBV promotes B cell lymphomagenesis in humanized mice and is found in human tumors. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 1487–1502.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!