- quantum field theory

- quantum field

- locality

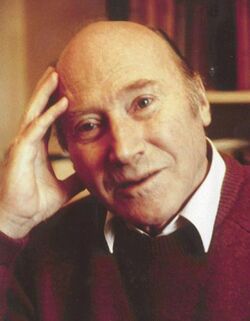

Basic Information

(Aug 1922–Jan 2016)

Location: Tübingen, Germany

1. Introduction

Rudolf Haag (17 August 1922 – 5 January 2016) was a German theoretical physicist, who mainly dealt with fundamental questions of quantum field theory. He was one of the founders of the modern formulation of quantum field theory and he identified the formal structure in terms of the principle of locality and local observables. He also made important advances in the foundations of quantum statistical mechanics.[1]

2. Biography

Rudolf Haag was born on August 17, 1922, in Tübingen, a university town in the middle of Baden-Württemberg. His family belonged to the cultured middle class. Haag's mother was the writer and politician Anna Haag.[2] His father, Albert Haag, was a teacher of mathematics at a Gymnasium. After finishing high-school in 1939, he visited his sister in London shortly before the beginning of World War II. He was interned as an enemy alien and spent the war in a camp of German civilians in Manitoba. There he used his spare-time after the daily compulsory labor to study physics and mathematics as an autodidact.[3]

After the war, Haag returned to Germany and enrolled at the Technical University of Stuttgart in 1946, where he graduated as a physicist in 1948. In 1951, he received his doctorate at the University of Munich under the supervision of Fritz Bopp[4] and became his assistant until 1956. In April 1953, he joined the CERN theoretical study group in Copenhagen[5] directed by Niels Bohr.[6][7] After a year, he returned to his assistant position in Munich and completed the German habilitation in 1954.[8] From 1956 to 1957 he worked with Werner Heisenberg at the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Göttingen.[9]

From 1957 to 1959, he was a visiting professor at Princeton University and from 1959 to 1960 he worked at the University of Marseille. He became a professor of Physics at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign in 1960. In 1965, he and Res Jost founded the journal Communications in Mathematical Physics. Haag remained the first editor-in-chief until 1973.[10] In 1966, he accepted the professorship position for theoretical physics at the University of Hamburg, where he stayed until he retired in 1987.[11] After retirement, he worked on the concept of quantum physical event.[12]

Haag developed an interest in music at an early age. He began learning the violin, but later preferred the piano, which he played almost every day. In 1948, Haag married Käthe Fues,[13] with whom he had four children, Albert, Friedrich, Elisabeth, and Ulrich. After retirement, he moved together with his second wife Barbara Klie[14] to Schliersee, a pastoral village in the Bavarian mountains. He died on January 5, 2016, in Fischhausen-Neuhaus, in southern Bavaria.[15]

3. Scientific Career

At the beginning of his career, Haag contributed significantly to the concepts of quantum field theory, including Haag's theorem, from which follows that the interaction picture of quantum mechanics does not exist in quantum field theory.[16] A new approach to the description of scattering processes of particles became necessary. In the following years Haag developed what is known as Haag–Ruelle scattering theory.[17]

During this work, he realized that the rigid relationship between fields and particles that had been postulated up to that point, did not exist, and that the particle interpretation should be based on Albert Einstein's principle of locality, which assigns operators to regions of spacetime. These insights found their final formulation in the Haag–Kastler axioms for local observables of quantum field theories.[18] This framework uses elements of the theory of operator algebras and is therefore referred to as algebraic quantum field theory or, from the physical point of view, as local quantum physics.[19]

This concept proved fruitful for understanding the fundamental properties of any theory in four-dimensional Minkowski space. Without making assumptions about non-observable charge-changing fields, Haag, in collaboration with Sergio Doplicher and John E. Roberts, elucidated the possible structure of the superselection sectors of the observables in theories with short-range forces.[20] Sectors can always be composes with one another, each sector satisfies either para-Bose or para-Fermi statistics and for each sector there is a conjugate sector. These insights correspond to the additivity of charges in the particle interpretation, to the Bose–Fermi alternative for particle statistics, and to the existence of antiparticles. In the special case of simple sectors, a global gauge group and charge-carrying fields, which can generate all sectors from the vacuum state, were reconstructed from the observables.[21][22] These results were later generalized for arbitrary sectors in the Doplicher–Roberts duality theorem.[23] The application of these methods to theories in low-dimensional spaces also led to an understanding of the occurrence of braid group statistics and quantum groups.[24]

In quantum statistical mechanics, Haag, together with Nicolaas M. Hugenholtz and Marius Winnink, succeeded in generalizing the Gibbs–von Neumann characterization of thermal equilibrium states using the KMS condition (named after Ryogo Kubo, Paul C. Martin, and Julian Schwinger) in such a way that it extends to infinite systems in the thermodynamic limit. It turned out that this condition also plays a prominent role in the theory of von Neumann algebras and resulted in the Tomita–Takesaki theory. This theory has proven to be a central element in structural analysis and recently[25] also in the construction of concrete quantum field theoretical models.[26] Together with Daniel Kastler and Ewa Trych-Pohlmeyer, Haag also succeeded in deriving the KMS condition from the stability properties of thermal equilibrium states.[27] Together with Huzihiro Araki, Daniel Kastler, and Masamichi Takesaki, he also developed a theory of chemical potential in this context.[28]

The framework created by Haag and Kastler for studying quantum field theories in Minkowski space can be transferred to theories in curved spacetime. By working with Klaus Fredenhagen, Heide Narnhofer, and Ulrich Stein, Haag made important contributions to the understanding of the Unruh effect and Hawking radiation.[29]

Haag had a certain mistrust towards what he viewed as speculative developments in theoretical physics[6] but occasionally dealt with such questions. The best known contribution is the Haag–Łopuszański–Sohnius theorem, which classifies the possible supersymmetries of the S-matrix that are not covered by the Coleman–Mandula theorem.[30][31]

4. Honors and Awards

In 1970 Haag received the Max Planck Medal for outstanding achievements in theoretical physics[32] and in 1997 the Henri Poincaré Prize[33] for his fundamental contributions to quantum field theory as one of the founders of the modern formulation.[1] Since 1980 Haag was a member of the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina[34] and since 1981 of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences.[35] Since 1979 he was a corresponding member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences[36] and since 1987 of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.[37]

5. Publications

5.1. Textbook

- Haag, Rudolf (1996). Local quantum physics: Fields, particles, algebras (2 ed.). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61458-3. ISBN 978-3-540-61049-6.

5.2. Selected Scientific Works

- Haag, Rudolf (1955). "On quantum field theories". Dan. Mat. Fys. Medd. 29 (12): 1–37. http://cds.cern.ch/record/212242. (Haag's theorem.)

- Haag, Rudolf (1958). "Quantum field theories with composite particles and asymptotic conditions". Physical Review 112 (2): 669–673. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.112.669. Bibcode: 1958PhRv..112..669H. (Haag–Ruelle scattering theory.)

- Haag, Rudolf; Kastler, Daniel (1964). "An Algebraic approach to quantum field theory". Journal of Mathematical Physics 5 (7): 848–861. doi:10.1063/1.1704187. Bibcode: 1964JMP.....5..848H. (Haag–Kastler axioms.)

- Doplicher, Sergio; Haag, Rudolf; Roberts, John E. (1971). "Local observables and particle statistics. 1". Communications in Mathematical Physics 23 (3): 199–230. doi:10.1007/BF01877742. Bibcode: 1971CMaPh..23..199D. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103857630.

- Doplicher, Sergio; Haag, Rudolf; Roberts, John E. (1974). "Local observables and particle statistics. 2". Communications in Mathematical Physics 35 (1): 49–85. doi:10.1007/BF01646454. Bibcode: 1974CMaPh..35...49D. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103859518. (Doplicher-Haag-Roberts analysis of the superselection structure.)

- Haag, Rudolf; Hugenholtz, Nico M.; Winnink, Marius (1967). "On the Equilibrium states in quantum statistical mechanics". Communications in Mathematical Physics 5 (3): 215–236. doi:10.1007/BF01646342. Bibcode: 1967CMaPh...5..215H. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103840050. (KMS condition.)

- Haag, Rudolf; Kastler, Daniel; Trych-Pohlmeyer, Ewa B. (1974). "Stability and equilibrium states". Communications in Mathematical Physics 38 (3): 173–193. doi:10.1007/BF01651541. Bibcode: 1974CMaPh..38..173H. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103860047. (Stability and KMS condition.)

- Araki, Huzihiro; Kastler, Daniel; Takesaki, Masamichi; Haag, Rudolf (1977). "Extension of KMS States and Chemical Potential". Communications in Mathematical Physics 53 (2): 97–134. doi:10.1007/BF01609126. Bibcode: 1977CMaPh..53...97A. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103900637. (KMS condition and chemical potential.)

- Haag, Rudolf; Narnhofer, Heide; Stein, Ulrich (1984). "On Quantum Field Theory in Gravitational Background". Communications in Mathematical Physics 94 (2): 219–238. doi:10.1007/BF01209302. Bibcode: 1984CMaPh..94..219H. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103941282. (Unruh effect.)

- Fredenhagen, Klaus; Haag, Rudolf (1990). "On the Derivation of Hawking Radiation Associated With the Formation of a Black Hole". Communications in Mathematical Physics 127 (2): 273–284. doi:10.1007/BF02096757. Bibcode: 1990CMaPh.127..273F. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104180137. (Hawking radiation.)

- Haag, Rudolf; Lopuszanski, Jan T.; Sohnius, Martin (1975). "All possible generators of supersymmetries of the S-matrix". Nuclear Physics B 88 (2): 257–274. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(75)90279-5. Bibcode: 1975NuPhB..88..257H. (Classification of Supersymmetry.)

- Haag, Rudolf (1990). "Fundamental Irreversibility and the Concept of Events". Communications in Mathematical Physics 132 (1): 245–252. doi:10.1007/BF02278010. Bibcode: 1990CMaPh.132..245H. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104201040. (Concept of Event.)

5.3. Others

- Buchholz, Detlev; Haag, Rudolf (2000). "The Quest for understanding in relativistic quantum physics". Journal of Mathematical Physics 41 (6): 3674–3697. doi:10.1063/1.533324. Bibcode: 2000JMP....41.3674B.

- Haag, Rudolf (2000). "Questions in quantum physics: A Personal view". Mathematical Physics 2000: 87–100. doi:10.1142/9781848160224_0005. ISBN 978-1-86094-230-3. Bibcode: 2000hep.th....1006H.

- Haag, Rudolf (2010). "Some people and some problems met in half a century of commitment to mathematical physics". The European Physical Journal H 35 (3): 263–307. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2010-10032-4. Bibcode: 2010EPJH...35..263H.

- Haag, Rudolf (2010). "Local algebras. A look back at the early years and at some achievements and missed opportunities". The European Physical Journal H 35 (3): 255–261. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2010-10042-7. Bibcode: 2010EPJH...35..255H.

- Haag, Rudolf (2015). "Faces of Quantum Physics". The Message of Quantum Science. Lecture Notes in Physics. 899. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 219–234. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46422-9_9. ISBN 978-3-662-46422-9.

- Haag, Rudolf (2019). "On quantum theory". International Journal of Quantum Information 17 (4): 1950037–1–9. doi:10.1142/S0219749919500370. Bibcode: 2019IJQI...1750037H.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biography:Rudolf_Haag

References

- "Henri Poincaré Prize citation". http://www.iamp.org/poincare/rh97-cit.html.

- Haag, Rudolf; Haag, Anna (2003) (in de). Leben und gelebt werden: Erinnerungen und Betrachtungen (1 ed.). Silberburg. ISBN 978-3874075626. Timms, Edward (2016). Anna Haag and her Secret Diary of the Second World War: A Democratic German Feminist's Response to the Catastrophe of National Socialism. Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. ISBN 978-3034318181.

- Kastler, Daniel (2003). "Rudolf Haag – Eighty years". Communications in Mathematical Physics 237 (1–2): 3–6. doi:10.1007/s00220-003-0829-1. Bibcode: 2003CMaPh.237....3K. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00220-003-0829-1

- The doctoral thesis is Haag, Rudolf (1951). Die korrespondenzmässige Methode in der Theorie der Elementarteilchen (Thesis) (in Deutsch). Munich. https://opac.ub.uni-muenchen.de/TouchPoint/perma.do?q=+0%3D%225363125%22+IN+%5B2%5D&l=en

- Since the laboratory in Geneva was still under construction, the study group was hosted by the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen.

- Haag, Rudolf (2010). "Some people and some problems met in half a century of commitment to mathematical physics". The European Physical Journal H 35 (3): 263–307. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2010-10032-4. Bibcode: 2010EPJH...35..263H. https://dx.doi.org/10.1140%2Fepjh%2Fe2010-10032-4

- "Closure of CERN's Theoretical Study Division in Copenhagen". https://timeline.web.cern.ch/closure-cerns-theoretical-study-division-copenhagen.

- The habilitation thesis is Haag, Rudolf (1954). On Quantum field theories (Thesis). 29. Copenaghen: Munksgaard in Komm. (published 1955). https://opac.ub.uni-muenchen.de/TouchPoint/perma.do?q=+0%3D%225874215%22+IN+%5B2%5D&l=en

- Buchholz, Detlev; Fredenhagen, Klaus (2016). "Nachruf auf Rudolf Haag" (in de). Physik Journal 15 (4): 53. https://www.pro-physik.de/restricted-files/85781.

- Jaffe, Arthur; Rehren, Karl-Henning (2016). "Rudolf Haag". Physics Today 69 (7): 70–71. doi:10.1063/PT.3.3244. Bibcode: 2016PhT....69g..70J. https://dx.doi.org/10.1063%2FPT.3.3244

- Schönhammer, Kurt (2016). "Nachruf auf Rudolf Haag. 17. August 1922 – 5. Januar 2016" (in de). Jahrbuch der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen: 236–237. doi:10.1515/jbg-2016-0026. https://dx.doi.org/10.1515%2Fjbg-2016-0026

- Haag, Rudolf (1990). "Fundamental Irreversibility and the Concept of Events". Communications in Mathematical Physics 132 (1): 245–252. doi:10.1007/BF02278010. Bibcode: 1990CMaPh.132..245H. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104201040. Haag, Rudolf (2015). "Faces of Quantum Physics". The Message of Quantum Science. Lecture Notes in Physics. 899. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 219–234. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46422-9_9. ISBN 978-3-662-46422-9. Haag, Rudolf (2019). "On quantum theory". International Journal of Quantum Information 17 (4): 1950037–1–9. doi:10.1142/S0219749919500370. Bibcode: 2019IJQI...1750037H.

- Käthe Fues was one of the daughters of the German theoretical physicist Erwin Fues.

- Haag married Barbara Klie after Käthe's premature death.

- Buchholz, Detlev; Doplicher, Sergio; Fredenhagen, Klaus (2016). "Rudolf Haag (1922 - 2016)". News Bulletin, International Association of Mathematical Physics: 27–31. http://www.iamp.org/bulletins/old-bulletins/Bulletin-January2016-print.pdf.

- Haag's theorem states that the usual Fock space representation cannot be used to describe interacting relativistic quantum fields with canonical commutation relations. One needs inequivalent Hilbert space representations of fields.

- See e.g. the review: Buchholz, Detlev; Summers, Stephen J. (2006). Encyclopedia of Mathematical Physics. Academic Press. pp. 456–465. doi:10.1016/B0-12-512666-2/00018-3. ISBN 978-0-12-512666-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FB0-12-512666-2%2F00018-3

- Brunetti, Romeo; Fredenhagen, Klaus (2006). Encyclopedia of Mathematical Physics. Academic Press. pp. 198–204. doi:10.1016/B0-12-512666-2/00078-X. ISBN 978-0-12-512666-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FB0-12-512666-2%2F00078-X

- Haag, Rudolf (1996). Local quantum physics: Fields, particles, algebras (2 ed.). Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61458-3. ISBN 978-3-540-61049-6. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-642-61458-3

- The only additional assumption to the Haag–Kastler axioms for the observables in this analysis was the postulate of the Haag duality, which was later established by Joseph J. Bisognano and Eyvind H. Wichmann in the framework of quantum field theory; the discussion of infinite statistics was also dispensed with.

- Fredenhagen, Klaus (2015). "An Introduction to Algebraic Quantum Field Theory". Advances in Algebraic Quantum Field Theory. Mathematical Physics Studies. Springer International Publishing. pp. 1–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21353-8_1. ISBN 978-3-319-21352-1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-319-21353-8_1

- Doplicher, Sergio; Haag, Rudolf; Roberts, John E. (1969). "Fields, observables and gauge transformations I". Communications in Mathematical Physics 13 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1007/BF01645267. Bibcode: 1969CMaPh..13....1D. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103841481. Doplicher, Sergio; Haag, Rudolf; Roberts, John E. (1969). "Fields, observables and gauge transformations II". Communications in Mathematical Physics 15 (3): 173–200. doi:10.1007/BF01645674. Bibcode: 1969CMaPh..15..173D. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1103841943.

- Doplicher, Sergio; Roberts, John E. (1989). "A new duality theory for compact groups". Inventiones Mathematicae 98: 157–218. doi:10.1007/BF01388849. Bibcode: 1989InMat..98..157D. Doplicher, Sergio; Roberts, John E. (1990). "Why there is a field algebra with a compact gauge group describing the superselection structure in particle physics". Communications in Mathematical Physics 131 (1): 51–107. doi:10.1007/BF02097680. Bibcode: 1990CMaPh.131...51D. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104200703.

- Fredenhagen, Klaus; Rehren, Karl-Henning; Schroer, Bert (1989). "Superselection Sectors with Braid Group Statistics and Exchange Algebras. 1. General Theory". Communications in Mathematical Physics 125 (2): 201. doi:10.1007/BF01217906. Bibcode: 1989CMaPh.125..201F. https://projecteuclid.org/euclid.cmp/1104179464. Fredenhagen, Klaus; Rehren, Karl-Henning; Schroer, Bert (1992). "Superselection sectors with braid group statistics and exchange algebras. 2. Geometric aspects and conformal covariance". Reviews in Mathematical Physics 4: 113–157. doi:10.1142/S0129055X92000170. Bibcode: 1992RvMaP...4S.113F. Froehlich, Juerg; Gabbiani, Fabrizio (1991). "Braid statistics in local quantum theory". Reviews in Mathematical Physics 2 (3): 251–354. doi:10.1142/S0129055X90000107.

- It is referred to the algebraic constructive quantum field theories born at the beginning of this century. They are different respect to the constructive theories mathematically developed in the 70s and 80s inspired by semiclassical ideas. See for example Summers' historical overview.

- An overview of the construction of a large number of models using these methods can be found in Lechner's chapter.

- Jäkel, Christian D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Mathematical Physics. Academic Press. pp. 227–235. doi:10.1016/B0-12-512666-2/00089-4. ISBN 978-0-12-512666-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FB0-12-512666-2%2F00089-4

- Longo, Roberto (2001). "Notes for a quantum index theorem". Communications in Mathematical Physics 222 (1): 45–96. doi:10.1007/s002200100492. Bibcode: 2001CMaPh.222...45L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs002200100492

- Kay, Bernard S. (2006). Encyclopedia of Mathematical Physics. Academic Press. pp. 202–212. doi:10.1016/B0-12-512666-2/00018-3. ISBN 978-0-12-512666-3. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FB0-12-512666-2%2F00018-3

- The theorem of Sidney Coleman and Jeffrey Mandula excludes a nontrivial coupling of bosonic inner symmetry groups with geometric symmetries (Poincaré group). The supersymmetry, on the other hand, allows such a coupling.

- Maldacena, Juan Martin (1998). "The Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity". Advances in Theoretical and Mathematical Physics 2 (4): 231–252. doi:10.1023/A:1026654312961. Martin, Stephen P. (2010). "A Supersymmetry Primer". Perspectives on Supersymmetry II. 21. 1–153. doi:10.1142/9789814307505_0001. ISBN 978-981-4307-48-2. Bibcode: 2010pesu.book....1M. https://dx.doi.org/10.1023%2FA%3A1026654312961

- "Max Planck Medal Prize winners" (in de). https://www.dpg-physik.de/auszeichnungen/dpg-preise/max-planck-medaille/preistraeger.

- "Henri Poincaré Prize winners". http://www.iamp.org/page.php?page=page_prize_poincare.

- "German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina member page of Rudolf Haag". https://www.leopoldina.org/en/members/list-of-members/list-of-members/member/Member/show/rudolf-haag/.

- "Göttingen Academy of Sciences member page of Rudolf Haag" (in de). https://adw-goe.de/en/members/personendetails/person/Rudolf-Haag/. (:Unkn) Unknown (2011). Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen. ed (in de). Jahrbuch der Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen 2010. De Gruyter. doi:10.26015/adwdocs-386. ISBN 978-3110236767.

- "Bavarian Academy of Sciences member page of Rudolf Haag". https://badw.de/en/data/footer-navigation/personentreffer.html?tx_badwdb_badwperson%5Bper_id%5D=1113&tx_badwdb_badwperson%5BpartialType%5D=BADWPersonDetailsPartial&tx_badwdb_badwperson%5Baction%5D=show&tx_badwdb_badwperson%5Bcontroller%5D=BADWPerson.

- "Austrian Academy of Sciences member page of Rudolf Haag". https://www.oeaw.ac.at/en/members-commissions/members-of-the-oeaw/all-members-at-a-glance/m/haag-rudolf.