Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the number one cause of death worldwide. Recent evidence has demonstrated an association between the gut microbiota and CVD, including heart failure, cerebrovascular illness, hypertension, and stroke. Marine algal polysaccharides (MAPs) are valuable natural sources of diverse bioactive compounds. MAPs have many pharmaceutical activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antidiabetic effects.

- cardiovascular diseases

- marine algae polysaccharides

- gut microbiota

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has become a major disease that threatens the health of human beings. CVD is a leading cause of death and morbidity worldwide. In China, approximately 40% deaths are attributed to CVD, which is higher than the cancer death rate or death rate from other diseases. CVD was a main cause of death in 2016, accounting for 45.50% in rural areas and 43.16% in cities [1]. The prevalence of CVD in China has been continuously increasing, and an upward trend will continue in the future. CVD includes coronary heart disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and stroke. The prevalence of CVD is also quickly rising in other developing nations (such as India and the African and Latin American continents), primarily due to diseases associated with atherosclerosis. In addition, viral and postinfectious diseases, which are also common in underdeveloped nations, have a negative impact on the heart and blood vessels [2]. In the USA, CVD is also the leading cause of mortality. Although the death rate of people with CVD has fallen over the previous few decades, nearly 2200 individuals died in the USA of CVD each day in 2016 [3]. According to estimates, 92.1 million people in the USA have at least one type of CVD, and by 2030, it is predicted that 44% of U.S. adults will suffer from more than one type of CVD [4]. As for Europe, Australia, and some developed countries in South America, the mortality rates of CVD are the lowest in the world. Despite this, CVD remains the main cause of death in Europe, approximately 42% and 52% for men and women each year [5]. The actual risk factors for CVD are becoming clearer, including high blood pressure, diabetes, obesity, high consumption of alcohol, inadequate physical activity, and unhealthy foods [6]. Frequent exposure to unhealthy foods, such as those high in sugar, fat, and salt, and a low consumption of dietary fiber leads to the gut microbiome’s dysbiosis. However, while still not fully understood, it has been recognized that the complex interactions between dietary fibers and the intestinal flora and gut-generated metabolites may play a significant role in CVD. There is increasing research attention to the gut microbiota as a strategy for the protection and treatment of CVD.

The human gut microbiome is a complex community predominantly found in the large intestine. Bacteria in the colon comprise hundreds of species and are present at levels of approximately 1011–1012 cells per mL of colonic content [7]. The majority of bacteria come from two phyla, Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes [8]. The gut microbiota is involved in degrading otherwise indigestible food components in the upper gastrointestinal tract, such as polysaccharides, into compounds that the host can absorb, and this process yields numerous functional metabolites, several of which have beneficial effects on the intestinal barrier and cardiovascular health. In addition, a rich and diverse gut microbiome leads to a well-balanced and healthy composition. A healthy gut ecosystem is critical to immune function and preventing disease development. Gut dysbiosis may play a role in a number of diseases; first and foremost are gastrointestinal diseases, which are the most studied, followed by those related to metabolic syndromes. There is also evidence that CVD is strongly correlated with the intestinal flora. Because of the complexity of the intestinal flora, researchers remain challenged to explore the roles of the intestinal flora and their functional metabolites in potential applications for the management of human health and CVD conditions.

Marine algae are far more abundant than other resources in the oceans. Marine algae contain a wide range of nutrients, including polysaccharides, proteins, peptides, amino acids, mineral salts, lipids, and polyphenols [9]. Among various nutrients, polysaccharides are the main constituents and key biological compounds in marine algae [10]. Lately, there has been an upsurge of interest in the pharmaceutical activities and potential applications of marine algal polysaccharides (MAPs). Several researchers have demonstrated that MAPs have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, antitumor, antibacterial, and antidiabetic activities in vivo, in vitro, and in clinical experiments [11,12,13,14,15,16]. MAPs are not digested directly in our upper gastrointestinal tract but can be utilized through fermentation by gut microorganisms [17]. This process may improve the gut microflora profile (such as the composition, diversity, and richness) and stimulate the production of functional metabolites by commensal bacteria.

2. Cardioprotective Effect of MAPs Associated with Gut Microbiota Modulation

Predictably, gut microbiota dysbiosis is most often associated with gastrointestinal disorders, which in turn influence the host immune response. Emerging evidence suggests an interaction between the gut microbiome and CVD, including atherosclerosis, hypertension, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, myocardial fibrosis, and heart failure [32]. Many studies have reported alterations in the diversity and composition of the gut bacteria in humans with CVD, as summarized in Table 2. For example, the obesity component, which is a CVD risk factor, is involved in the development of dysbiotic gut microbiota, an imbalance favoring Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in obesity in humans and animals [33].

Bacteroides species are anaerobic gut commensals in humans and are recognized as conferring a myriad of benefits to the human host. Among them is the provision of energy from a variety of MAPs that are known to produce several secondary metabolites that are beneficial to the intestinal mucosal layer and decorate the surface of other microbes [34,35]. Bacteroides species exhibit genome-encoded carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZymes), which can hydrolyze glycoside linkages by following the release of the reducing sugars from MAPs [36]. CAZymes have five classes of carbohydrases: glycoside hydrolase (GH), glycosyltransferase (GT), polysaccharide lyase (PL), carbohydrate esterase (CE), auxiliary activities, and carbohydrate-binding module (CBM). Nguyen et al. reported a significant increase in Bacteroides with higher energy metabolism due to a laminarin-supplemented high-fat diet [37]. They showed a higher abundance of CAZymes in laminarin-supplemented high-fat diet mice compared to high-fat diet mice, with especially dramatic increases in glycoside hydrolases and polysaccharide lyases, including GT2, GT4, GH2, CE8, CE12, PL1, and PL10. Porphyran from Porphyra haitanensis decreased lipid accumulation and maintained gut microbiota homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice, including an increase in the relative proportion of Bacteroides, Roseburia, and Eubacterium and a marked reduction in Helicobacter.

Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes represent greater than 90% of the total bacteria community, while the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was reported to be increased in spontaneously hypertensive rats [33]. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio has emerged as a possible characteristic for gut dysbiosis and CVD risk factors. A low Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio was found to be strongly correlated with a balanced immune status and is generally considered beneficial for health [38]. Several studies have demonstrated that polysaccharides derived from natural resources efficiently reduced the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. Sargassum pallidum polysaccharides modulated the gut microbiota composition by decreasing the ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes and enhancing the relative proportion of some beneficial genera, such as Bacteroides, Dialister, Phascolarctobacterium, Prevotella, and Ruminococcus when investigated by in vitro fermentation assay [39]. MAPs treatment can reduce the ratio of Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes, as verified in an in vivo CVD risk model. The green alga Enteromorpha prolifera polysaccharide showed anti-hyperuricemic effects, including significantly lowering the level of serum uric acid, xanthine oxidase, and blood urea nitrogen. Enteromorpha prolifera polysaccharide maintained the stability of the intestinal flora and showed a significant decrease in the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio [40].

An increase in the growth of Akkermansia muciniphila has been found to be favorable for the prevention of type 2 diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, and other metabolic syndromes. Akkermansia is the only genus of the phylum Verrucomicrobia found in gastrointestinal samples. In high-fat diet-induced obese mice, the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila was strongly correlated with the expression of fat metabolism and inversely related with inflammation in adipose tissue and circulating glucose, adiponectin, leptin, triglycerides, and insulin [41]. Shang et al. reported that Enteromorpha clathrata polysaccharides dramatically elevated the relative abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium spp., and Lactobacillus spp. in the gut [42]. In addition, they demonstrated a similar beneficial pharmacological effect of two fucoidans from Laminaria japonica and Ascophyllum nodosum on diet-induced metabolic damage in the C57BL/6 J mice model, which increased the abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila, Alloprevotella, Blautia, and Bacteroides treatment by fucoidan [43].

Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species are well-known probiotics that beneficially affect the host organism by improving and modulating the intestinal flora and preventing CVD [44]. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains possess different degrees of cholesterol removal from the media through cholesterol assimilation during growth, the binding capacity of cholesterol to cells, the incorporation of cholesterol into the cytoplasmic membrane, and bile salt deconjugation [45]. Alginate oligosaccharide treatment improved fat metabolism and inflammation by regulating the intestinal microbiota in high-fat diet-induced gut dysbiosis mice, especially by increasing the abundance of Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus reuteri [46]. Undaria pinnatifida polysaccharide intervention significantly reduced the fasting blood glucose levels, mitigated the impaired glucose tolerance, and improved insulin resistance in diabetic rats by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, such as Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Faecalibaculum, Lachnoclostridium, and Olsenella [47].

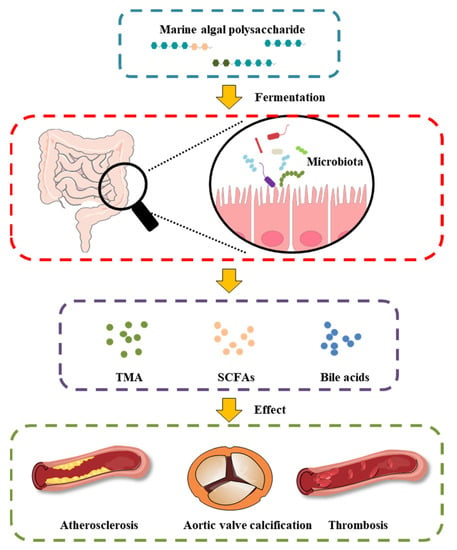

MAPs play an important role in the intestinal microenvironment reconstruction, based on both richness and diversity. We suggest that the therapeutic manipulation of the intestinal microbiota with MAPs may be a successful treatment selection to restore gut microbiota composition and potentiate heart failure management (Figure 2). Undigested MAP can be fermented by intestinal microbiota for their growth and the production of secondary metabolites, such as SCFAs, bile acids, and TMA.

Table 2. Marine algal polysaccharides and their effect on CVD prevention through gut microbiota.

| Type of Polysaccharides | Marine Algae Sources | Influence on Intestinal Microbiota | Treatment and Prevention of CVD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alginate | Sargassum fusiforme | Lactobacillus, Bacteroides, Akkermansia Alloprevotella, Weissella, and Enterorhabdus ↑ Turicibacter and Helicobacter ↓ |

attenuated pathological changes in adipose, hepatic, and heart tissues; diminished oxidative stress | [48] |

| carrageenan | Kappaphycus Alvarezii | Parasutterella, Alloprevotella, Oscillibacter, Melainabacteria, and Butyricimonas ↑ Clostridia, Erysipelotrichaceae, Blautia, and Lachnospiraceae ↓ |

decreased total cholesterol and high-density level cholesterol; reduced adipocyte size and levels of adiponectin and leptin | [49] |

| fucan | Saccharina japonica | Bacteroides sartorii, Bacteroides acidifaciens, Akkermansia, and Lachnospiraceae NK4A136 ↑ | prevented high-fat diet-induced obesity; regulated blood glucose/lipid metabolism | [50] |

| fucoidan | Laminaria japonica | phylum Bacteroidetes and families Muribaculaceae and Bacteroidaceae ↑ | ameliorated high-fat diet-induced body weight gain, fat accumulation, serum lipid profiles, insulin resistance, hepatic steatosis, and adipocyte hypertrophy | [51] |

| fucoidan | Sargassum fusiforme | Bacteroides, Faecalibacterium, and Blautia ↑ | reduced epididymal fat deposition, decreased oxidative stress, and attenuated the pathological changes in heart tissues | [52] |

| fucoidan | Sargassum fusiforme | Bacteroides, Ruminococcaceae, and Butyricoccus↑ Helicobacter↓ |

reduced fat accumulation; enhanced the energy expenditure through increasing the expression of uncoupling protein 1 in adipose tissues | [53] |

| porphyran | Porphyra haitanensis | Roseburia and Eubacterium ↑, Helicobacter ↓ | ameliorated body fat accumulation in liver, serum, and adipose tissues; increased the pathway of PGC 1α-UCP 1-mitochondrial to produce more energy |

[54] |

| porphyran | Neoporphyra haitanensis | Parabacteroides and Coriobacteriaceae UCG-002 ↑ | inhibited G6Pase and PEPCK enzymes related to hepatic gluconeogenesis; enhanced the expression of the GLUT4 enzyme involved in peripheral glucose uptake | [55] |

| ulvan | Enteromorpha prolifera | Desulfovibrio ↑, modulated Verrucomicrobiaceae, Odoribacteraceae, Mogibacteriaceae, Planococcaceae, and Coriobacteriaceae | decreased levels of inflammatory factors, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6; increased total antioxidant capacity and superoxide dismutase, glutathione, catalase, and telomerase levels | [56] |

| ulvan | Ulva lactuca | Dubosiella, Lactobacillus, and Parasutterella ↑ Staphylococcus, Escherichia−Shigella, and Ruminococcus ↓ |

reduced the amount of blood urea nitrogen, serum uric acid, and creatinine; suppressed the activities of serum and hepatic xanthine oxidase | [57] |

Figure 2. Effect of MAP on the intestinal microbiota and gut-derived metabolites in CVD.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/foods11223550

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!