The complementary interaction of microRNAs (miRNAs) with their binding sites in the 3′untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of target gene mRNAs represses translation, playing a leading role in gene expression control. MiRNA recognition elements (MREs) in the 3′UTRs of genes often contain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which can change the binding affinity for target miRNAs leading to dysregulated gene expression. Accumulated data suggest that these SNPs can be associated with various human pathologies (cancer, diabetes, neuropsychiatric disorders, and cardiovascular diseases) by disturbing the interaction of miRNAs with their MREs located in mRNA 3′UTRs. Numerous data show the role of SNPs in 3′UTR MREs in individual drug susceptibility and drug resistance mechanisms. In this review, we brief the data on such SNPs focusing on the most rigorously proven cases. Some SNPs belong to conventional genes from the drug-metabolizing system (in particular, the genes coding for cytochromes P450 (CYP 450), phase II enzymes (SULT1A1 and UGT1A), and ABCB3 transporter and their expression regulators (PXR and GATA4)). Other examples of SNPs are related to the genes involved in DNA repair, RNA editing, and specific drug metabolisms. We discuss the gene-by-gene studies and genome-wide approaches utilized or potentially utilizable to detect the MRE SNPs associated with individual response to drugs.

1. Introduction

Recently, large scale sequencing and genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified tens of thousands of variants (mainly, single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) associated with various human traits and diseases [

1,

2,

3]. Of them, nearly 90% are located in noncoding regions [

4,

5] and can impact gene expression in several ways. A large group of the SNPs mainly residing in promoter and enhancer regions influences transcription initiation by creating or disrupting transcription factor binding sites or changing the affinity of transcription factors for their cognate sites [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Many SNPs affect RNA splicing [

6,

10]. In addition, 3′untranslated regions (3′UTRs) of genes often contain the variants which are able to change the binding affinity of targeting miRNAs, thereby interfering with gene expression at a posttranscriptional level [

11,

12].

According to the current data, miRNAs interact in a complementary manner with their sites in the 3′UTRs of the mRNAs of target genes causing template degradation and translational repression, thus playing a leading role in the posttranscriptional mechanisms of gene expression regulation [

13]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs), an evolutionarily conserved class of endogenous 18–24-nucleotide noncoding RNAs, form a RISC complex together with one of the AGO family proteins and auxiliary proteins and are involved in translation repression or cleavage of target mRNAs [

14,

15]. So far, over 2600 miRNAs have been identified in humans [

16]. One miRNA has the potential to target many genes (on the average, approximately 500 genes) and, according to the estimates, over 60% of the human mRNAs are potential targets of miRNAs [

17].

Currently, a significant amount of data suggest that the coordinated action of miRNAs plays an important role in the regulation of biological processes, including the cell cycle, cell growth and differentiation, migration, apoptosis, and stress response [

18]. Numerous studies have also shown that an altered expression of miRNAs contributes to the development of a wide range of human pathologies, such as cancer, diabetes, neuropsychiatric disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and infection diseases [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. The SNPs interfering with the interaction of miRNAs with their target sites, located in both miRNA seed sequences and mRNA 3′UTRs, are frequently associated with the same diseases (for review, see [

12]). In addition, some data suggest the involvement of SNPs in 3′UTR miRNA target sequences in individual drug susceptibility and drug resistance mechanisms [

24,

25,

26].

2. Modern Approaches to Identify Functional SNPs in 3′UTR miRNA Target Sequences

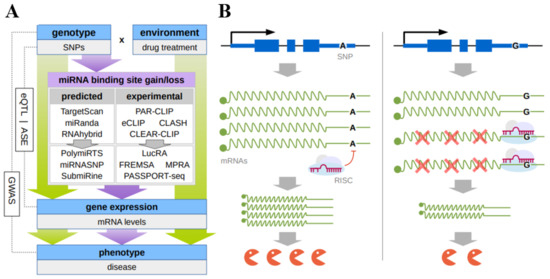

An integrated set of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo approaches has been designed so far to detect the SNPs located in mRNA 3′UTRs and influencing (both deteriorating and enhancing) the interaction of miRNAs with their target sites (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. (A) Principal scheme of discovery of functional SNPs that result in changes of microRNA binding to their response elements in the mRNA 3’UTR; (B) the hypothetical mechanism of the individual drug response due to the mirSNP. SNP(A>G) in 3′UTR of mRNA leads to the gain of the miRNA response element allowing miRNA-mRNA binding which hinders gene expression at a posttranscriptional level.

As a rule, in silico approaches rely on a certain algorithm predicting miRNA binding sites that make it possible to assess the functionality of these sites or correspondingly rank them based on the type of seed match, site accessibility, evolutionary conservation, nucleotide environment, thermodynamic characteristics of the duplex, and so on. In particular, the databases PolymiRTS 3.0 (

http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/) (accessed on 10 October 2022) and miRNASNP-v3 (

http://bioinfo.bjmu.edu.cn/mirsnp/search/) (accessed on 10 October 2022) or the tool SubmiRine (

https://research.nhgri.nih.gov/software/SubmiRine/) (accessed on 10 October 2022) use the popular de novo prediction algorithm TargetScan (

http://www.targetscan.org/vert_71/) (accessed on 10 October 2022). This algorithm utilizes the so-called context+ score regression model to assess the site efficiency, which takes into account the contribution of the parameters, such as seed-pairing stability, target-site abundance, local AU content, site location within 3′UTR, and 3′-supplementary pairing (and a more recent context++ model, based on 14 parameters, including the degree of site conservation). Thus, the SNPs are selected that either differ in their context+ score or absent in one of the allelic variants. An alternative in silico approach used, in particular, in miRNASNP-v3, as well as popular and effective in silico method to study individual sites is the calculation of the minimum free energy (MFE) of hybridization between a miRNA seed and its cognate mRNA target (for example, using MicroInspector, RNAfold and RNAhybrid) [

27,

28,

29].

A set of experimental approaches allowing for gene-by-gene or genome-wide studies is used to verify the obtained predictions. The main in vitro gene-by-gene approaches are luciferase reporter assay and fluorescent-based RNA electrophoretic mobility shift assay (FREMSA or simply RNA EMSA).

The luciferase reporter assay is used in almost all studies on assessment of the effect of a nucleotide substitution on the efficiency of miRNA–mRNA interaction. This method utilizes the plasmid constructs carrying a mutated or a reference allele of miRNA recognition site located in the mRNA 3′UTR inserted downstream of the reporter luciferase gene. Each plasmid construct is transfected alone [

30] or cotransfected with the miRNA into the culture of selected eukaryotic cells to monitor the reporter expression [

31]. Either siRNA overexpressing plasmids [

32], miRNA mimics (individually [

11,

27,

28,

33] or a library of miRNA mimics [

34] are used for cotransfection. Deletion and mutagenesis of the putative miRNA response element (MRE) in the plasmid construct are used to confirm the location of binding site for each miRNA [

35]. Both transient [

11,

27,

28,

33] and stable transfection of cultivated cells with the plasmid reporter construct with concurrent cotransfection of mimic miRNA are used [

36].

Although many papers assert that the luciferase reporter assay is able to determine the differences in the binding affinities between the wild-type and alternative alleles, this method in fact can record only the suppressive effect of a miRNA on the expression of its putative targets [

31,

32,

37], which only allows the effect of the corresponding nucleotide substitution on the affinity of miRNA–mRNA interaction to be assumed. In addition, a considerable limitation of this method is the tissue-specificity of the studied effects, which requires that several cell lines are used [

38].

FREMSA is an in vitro technique which is able to provide direct evidence of the interaction between miRNA and mRNA and to assess the effect of an SNP on the efficiency of this interaction [

27,

39,

40]. This method utilizes the RNA oligonucleotides corresponding to the mature miRNA species and the cognate mRNA fragments corresponding to the miRNA targeting sequences. The fragments are 5′-labeled with different fluorescent dyes. The reaction mixture is separated by gel electrophoresis; the bands representing miRNAs, mRNAs, and miRNA–mRNA complexes are visualized according to different wavelengths of fluorescence dyes [

27,

39,

40].

Correlation analysis of the expression of the miRNA and mRNA carrying different alleles in tissue samples is an informative in vivo method, widely used to assess the potential regulatory effects of miRNAs on their targets [

32,

34,

41]. Another approach utilizes the transient transfection of primary human cells with miRNA mimics or the miRNA mimic negative controls in order to evaluate their influence on the target enzyme activity or mRNA concentrations [

35]. The miRNA inhibitors, leading to a decrease in their levels in cells and the coupled decrease in the levels of mRNA targets, are also used [

28].

To date, over 400,000 SNPs have been identified in putative miRNA binding sites (mirSNPs) by in silico methods, which poses the challenge of designing the genome-wide approaches to search for functional SNPs affecting miRNA binding [

38]. The advent of state-of-the-art genome-wide technologies has brought about some such methods. In particular, the MPRA (massive parallel reporter analysis) [

42] made it possible in 2018 to develop the PASSPORT-seq (parallel assessment of polymorphisms in miRNA target sites by sequencing) approach, which involves pooled synthesis, parallel cloning, and single-well transfection followed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) to functionally test hundreds of mirSNPs at once [

38]. First, the utility of the assay was demonstrated by study of 100 randomly selected mirSNPs in HEK293, HepG2, and HeLa cells. Using traditional individual luciferase assay, a gold-standard platform for in vitro assessing gene expression, 17 of the tested 21 PASSPORT-seq results were confirmed. Second, the application of PASSPORT-seq technology to 111 mirSNPs in 3′UTR of 17 pharmacogenes showed a significant effect of 33 variants in at least one cell line (HeLa, HepG2, HEK293, or HepaRG). Several examples from this list are included below.

NGS was also used to design AGO crosslinking immunoprecipitation (CLIP) technologies that allow for the identification of endogenously relevant transcriptome-wide sites bound by AGO (eCLIP, PAR-CLIP, and HITS-CLIP). However, these technologies fail to reveal which particular miRNAs bind to each mRNA target [

43,

44]. A ligation step added to the CLIP technology makes it possible to sequence the chimeric miRNA–mRNA molecules, thereby showing the pairs that have hybridized (crosslinking, ligation, and sequencing of hybrids, CLASH) [

45]. Powell et al. [

44] used this approach to generate a liver-expressed pharmacogene-relevant map of miRNA–mRNA interactions and target sites. In their study, the chimeric-eCLIP was used to experimentally define the miRNA–mRNA interactome in primary human hepatocytes from a pool of 100 donors. Based on these results, an extensive map of miRNA binding of each gene was developed, including the pharmacogenes expressed in primary hepatocytes. Using the high-throughput PASSPORT-seq assay in HepaRG cells, they further tested the functional impact of 262 genetic variants in these miRNA binding sites. These 262 variants were selected among approximately 3600 PharmGKB variants as having the coordinates overlapping their chimeric-eCLIP–identified target sites. As a result, they discovered 24 mirSNPs considered to be functional in HepaRG cells. The share of the detected functional SNPs in their work is lower as compared with the earlier study of this group reported by Ipe et al. [

38] although both studies were carried out using the same approach. The putative cause of this discrepancy is that in the later study Powell et al. used only one cell line versus four lines used in the earlier study by Ipe et al. [

44]. Another possible cause is that in the later study [

44] the SNPs were involved initially localized not only in 3′UTR, but also in the gene coding regions. In particular, the combination of chimeric-eCLIP with PASSPORT-seq successfully identified the functional mirSNPs at the end of the DPYD pharmacogene coding region that influenced the hsa-mir-27b interaction with the earlier validated binding site [

46]. Note that these results suggest a potentially important role of the binding to target sequences not only in the 3′UTR but in the coding regions as well.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms232213725