Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a growing metabolic disease characterized by insulin resistance and hyperglycemia. Current preventative and treatment approaches to insulin resistance and T2DM lack in efficacy, resulting in the need for new approaches to prevent and treat the disease. In recent years, epidemiological studies have suggested that diets rich in fruits and vegetables have beneficial health effects, including protection against insulin resistance and T2DM. Curcumin, a polyphenol found in turmeric, and curcuminoids have been reported to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, nephroprotective, neuroprotective, immunomodulatory and antidiabetic properties. Here we are summarizing the existing in vivo studies examining the antidiabetic effects of curcumin.

- insulin resistance

- diabetes

- curcumin

- curcuminoids

- in vivo

- animal studies

- human studies

1. Introduction

Insulin resistance is characterized by a reduction in the responsiveness of target tissues to the normal circulating levels of insulin [1][2][3]. Insulin resistance and T2DM are associated with inflammation, obesity, ageing and a sedentary lifestyle, and results in hyperglycemia, a state of elevated plasma glucose levels [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. Hyperglycemia can lead to long-term complications including macrovascular and microvascular damage, cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy [1][2][3][4][5][6][7].

Epidemiological studies have suggested that diets rich in fruit and vegetables help regulate body weight (obesity) and protect against cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes [8][9][10]. However, it is difficult to determine the role of food components in disease prevention and treatment. Specific components, known as polyphenols, have gained attention within the scientific community for their potential health benefits and preventative and therapeutic properties against chronic diseases [11][12][13][14][15][16].

Polyphenols have been established to have antioxidant properties [17] and to possess a variety of other biological effects such as regulating enzymes [18][19][20]. Therefore, they may prevent diseases through mechanisms that are both dependent and independent of their antioxidant properties [18][19][20].

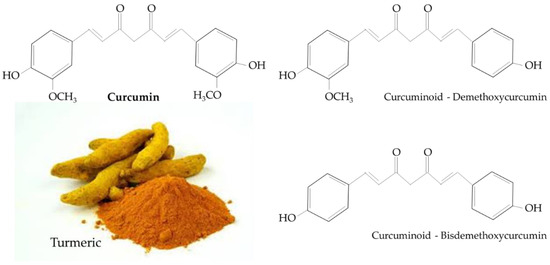

Turmeric is a rhizomatous medicinal perennial plant (Curcuma longa) and has a rich history of being used in Asian countries, such as China, India, Indonesia, and Thailand [21][22]. The main natural polyphenol in C. longa and in other Curcuma species is known as either curcumin (1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione), or diferuloylmethane [22]. Other curcuminoids, such as demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin, are structurally similar to curcumin and differ only with respect to the number of methoxy groups on the aromatic rings (Figure 1) [22].

Figure 1. Chemical structure of curcumin and curcuminoids found in turmeric.

Despite the reported benefits of curcumin by its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant mechanisms, curcumin’s poor bioavailability caused by its poor absorption, rapid metabolism and rapid elimination, limits its potential [23] [24]. Further research is needed to examine the bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of curcumin.

We have searched the scientific literature focusing on the studies investigating the antidiabetic properties of curcumin. We have summarized all the available information, and presented it in two review manuscripts. The first manuscript (Antidiabetic properties of curcumin I: Evidence from in vitro studies) [25] focuses on the in vitro evidence (Nutrients, 2020;12(1)). The second manuscript (Antidiabetic properties of curcumin II: Evidence from in vivo studies) [26] focuses on the in vivo evidence (Nutrients, 2019; 12(1)).

2. Effects of Curcumin

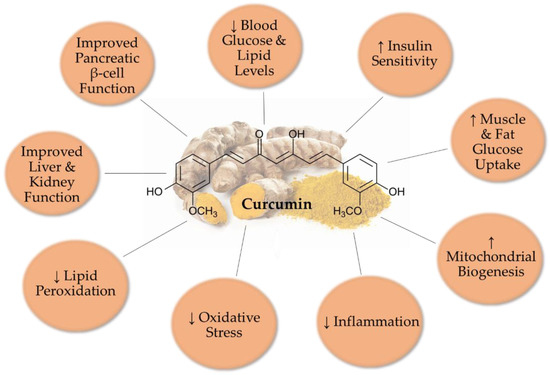

Overall, all available in vivo animal studies examining the effects of curcumin indicate significantly improved glucose and lipid homeostasis (Figure 2). Serum glucose and lipid levels were significantly reduced. Oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation were reduced with curcumin treatment, while antioxidant enzyme activities were increased. In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and macrophage infiltration to adipose and liver tissues were reduced. Furthermore, mitochondrial biogenesis was improved with curcumin administration. Administration of curcumin to animal models of diabetic nephropathy resulted in improved kidney function.

Figure 2. Overall effects of curcumin in T2DM animal models.

The in vivo studies presented in our review may have used different curcumin dosages and different treatment times. A careful examination of the animal studies revealed that overall, in STZ-induced, diet-induced and genetic models of diabetes, the common doses of curcumin were 100–300 mg/kg b.w./day for 8 weeks.

The doses of curcumin in human clinical trials were 200–500 mg/day and the common treatment time was around 12 weeks. A number of studies have indicated that the use of different drug delivery systems, such as curcumin loaded nanoparticles, liposomes, cyclodextrin inclusions and microemulsions, can result in an increased bioavailability of curcumin and improved action [27][28][29]. We recognize and propose that more human studies should be performed to investigate and establish the effective dose of curcumin. In addition, the detailed effects of curcumin administration on plasma glucose, lipid, insulin and HbA1c levels should be explored.

Many other polyphenols and natural compounds such as resveratrol, naringenin, cinnamon, capsaicin, berberine, genistein and others have been shown to have antidiabetic properties [27][28]. Although increased antioxidant intake has been traditionally thought to result in health benefits [30][31][32], this notion has been challenged lately [33][34], and recent evidence indicates that excess antioxidant intake may increase the risk of certain diseases. Therefore, agents with antioxidant potential, including curcumin, should be studied extensively before recommendations for human supplementation are approved.

The limited human studies indicate that curcumin administration can improve glucose homeostasis and reduce the diabetic phenotype with reduced blood glucose levels and reduced insulin resistance. However, more research must be conducted to fully understand the effects of curcumin in specific tissues of the body, particularly skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, liver and pancreatic β-cells.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu12010058

References

- Devjit Tripathy; Alberto O. Chavez; Defects in Insulin Secretion and Action in the Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Current Diabetes Reports 2010, 10, 184-191, 10.1007/s11892-010-0115-5.

- Alan R. Saltiel; New perspectives into the molecular pathogenesis and treatment of type 2 diabetes.. Cell 2001, 104, 517-529, 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00239-2.

- M. Ashraful Alam; Nusrat Subhan; M. Mahbubur Rahman; Shaikh J. Uddin; Hasan M. Reza; Satyajit D. Sarker; Effect of citrus flavonoids, naringin and naringenin, on metabolic syndrome and their mechanisms of action.. Advances in Nutrition 2014, 5, 404-17, 10.3945/an.113.005603.

- Patrick Schrauwen; Vera Schrauwen-Hinderling; Joris Hoeks; Matthijs K.C. Hesselink; Mitochondrial dysfunction and lipotoxicity. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2010, 1801, 266-271, 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.011.

- Tushar P. Patel; Sanket Soni; Pankti Parikh; Jeetendra Gosai; Ragitha Chruvattil; Sarita Gupta; Swertiamarin: An Active Lead from Enicostemma littorale Regulates Hepatic and Adipose Tissue Gene Expression by Targeting PPAR-γ and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Experimental NIDDM Rat Model. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 2013, 1-11, 10.1155/2013/358673.

- Banting and Best Memorial Lecture. Diabetic Medicine 2006, 23, 458-458, 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.02038_7.x.

- María E. Frigolet; Nimbe Torres; Armando R. Tovar; The renin–angiotensin system in adipose tissue and its metabolic consequences during obesity. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2013, 24, 2003-2015, 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.07.002.

- A. R. Vieira; L. Abar; Snieguole Vingeliene; D. S. M. Chan; D. Aune; D. Navarro-Rosenblatt; C. Stevens; D. Greenwood; T. Norat; Fruits, vegetables and lung cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology 2016, 27, 81-96, 10.1093/annonc/mdv381.

- Jessica N. Kuzma; Kelsey A. Schmidt; Mario Kratz; Prevention of metabolic diseases: fruits (including fruit sugars) vs. vegetables.. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 2017, 20, 286-293, 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000378.

- Stefan, N.; Häring, H.-U.; Schulze, M.B. Metabolically healthy obesity: the low-hanging fruit in obesity treatment? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2018, 6, 249–258.

- Joseph A. Baur; David A. Sinclair; Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 493-506, 10.1038/nrd2060.

- Eun-Jung Park; John M. Pezzuto; The pharmacology of resveratrol in animals and humans. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2015, 1852, 1071-1113, 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.01.014.

- Alexa Serino; Gloria Salazar; Protective Role of Polyphenols against Vascular Inflammation, Aging and Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2018, 11, 53, 10.3390/nu11010053.

- Jessy Moore; Michael Yousef; Evangelia Tsiani; Anticancer Effects of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) Extract and Rosemary Extract Polyphenols. Nutrients 2016, 8, 731, 10.3390/nu8110731.

- Michael Yousef; Ioannis A. Vlachogiannis; Evangelia Tsiani; Effects of Resveratrol against Lung Cancer: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1231, 10.3390/nu9111231.

- Madina Naimi; Filip Vlavcheski; Hesham Shamshoum; Evangelia Tsiani; Rosemary Extract as a Potential Anti-Hyperglycemic Agent: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Nutrients 2017, 9, 968, 10.3390/nu9090968.

- Ivor E Dreosti; Antioxidant polyphenols in tea, cocoa, and wine.. Nutrition 2000, 16, 692-694, 10.1016/s0899-9007(00)00304-x.

- Marie Lagouge; Carmen Argmann; Zachary Gerhart-Hines; Hamid Meziane; Carles Lerin; Frédéric Daussin; Nadia Messadeq; Jill Milne; Philip Lambert; Peter Elliott; et al. Resveratrol Improves Mitochondrial Function and Protects against Metabolic Disease by Activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109-1122, 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013.

- Souheila Amor; Pauline Châlons; Virginie Aires; Dominique Delmas; Polyphenol Extracts from Red Wine and Grapevine: Potential Effects on Cancers. Diseases 2018, 6, 106, 10.3390/diseases6040106.

- Rosaria Vari Carmela Santangelo; Anti-inflammatory Activity of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Polyphenols: Which Role in the Prevention and Treatment of Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases?. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders-Drug Targets 2017, 18, , 10.2174/1871530317666171114114321.

- Kocaadam, B.; Şanlier, N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 2889–2895.

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Biswas, K.; Bandyopadhyay, U.; Banerjee, R.K. Turmeric and curcumin: Biological actions and medicinal applications. Cur Sci 2004, 87, 10.

- Guido Shoba; David Joy; Thangam Joseph; M. Majeed; R. Rajendran; P. Srinivas; Influence of Piperine on the Pharmacokinetics of Curcumin in Animals and Human Volunteers. Planta Medica 1998, 64, 353-356, 10.1055/s-2006-957450.

- Bo Meng; Jun Li; Hong Cao; Antioxidant and antiinflammatory activities of curcumin on diabetes mellitus and its complications.. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2013, 19, , .

- Danja J. Den Hartogh; Alessandra Gabriel; Evangelia Tsiani; Antidiabetic Properties of Curcumin I: Evidence from In Vitro Studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 118, 10.3390/nu12010118.

- Danja J. Den Hartogh; Alessandra Gabriel; Evangelia Tsiani; Antidiabetic Properties of Curcumin II: Evidence from In Vivo Studies. Nutrients 2019, 12, 58, 10.3390/nu12010058.

- Wang, S.; Tan, M.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, M.; Wang, Y. Nanotechnologies for Curcumin: An Ancient Puzzler Meets Modern Solutions Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jnm/2011/723178/ (accessed on Dec 17, 2019).

- Gagan Flora; Deepesh Gupta; Archana Tiwari; Nanocurcumin: a promising therapeutic advancement over native curcumin.. Critical Reviews™ in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems 2013, 30, 331-368, 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.2013007236.

- Susan J. Hewlings; Douglas S. Kalman; Curcumin: A Review of Its’ Effects on Human Health. Foods 2017, 6, 92, 10.3390/foods6100092.

- B.H. Thiers; Mortality in Randomized Trials of Antioxidant Supplements for Primary and Secondary Prevention: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Yearbook of Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery 2008, 2008, 252-253, 10.1016/s0093-3619(08)70874-8.

- Katsiki, N.; Manes, C. Is there a role for supplemented antioxidants in the prevention of atherosclerosis? Clin Nutr 2009, 28, 3–9

- Davide Bolignano; Valeria Cernaro; Guido Gembillo; Rossella Baggetta; Michele Buemi; Graziella D’Arrigo; Antioxidant agents for delaying diabetic kidney disease progression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0178699, 10.1371/journal.pone.0178699.

- Halliwell, B. The antioxidant paradox: less paradoxical now? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013, 75, 637–644.

- Zai-Qun Liu; Antioxidants may not always be beneficial to health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 131-133, 10.1016/j.nut.2013.04.006.