Pigeon toe, also known as in-toeing, is a condition which causes the toes to point inward when walking. It is most common in infants and children under two years of age and, when not the result of simple muscle weakness, normally arises from underlying conditions, such as a twisted shin bone or an excessive anteversion (femoral head is more than 15° from the angle of torsion) resulting in the twisting of the thigh bone when the front part of a person's foot is turned in.

- infants and children

- in-toeing

- anteversion

1. Causes

The cause of in-toeing can be differentiated based on the location of the misalignment. The variants are:[1][2]

- Curved foot (metatarsus adductus)

- Twisted shin (tibial torsion)

- Twisted thighbone (femoral anteversion)

1.1. Metatarsus Adductus

The most common form of being pigeon toed, when the feet bend inward from the middle part of the foot to the toes. This is the most common congenital foot abnormality, occurring every 1 in 5,000 births.[3][4] The rate of metatarsus adductus is higher in twin pregnancies and preterm deliveries.[3] Most often self-resolves by one year of age and 90% of cases will resolve spontaneously (without treatment) by age 4.[5]

Signs and Symptoms[3]

- C-shaped lateral border of foot

- Intoeing gait

- Pressure sites during shoe wear

1.2. Tibial Torsion

The tibia or lower leg slightly or severely twists inward when walking or standing. Usually seen in 1-3 year olds, internal tibial torsion is the most common cause of intoeing in toddlers.[3] It is usually bilateral (both legs) condition that typically self-resolves by 4 to 5 years of age.[3][4]

Signs and Symptoms[3]

- Frequent tripping and clumsiness

- Intoeing gait

1.3. Femoral Anteversion

The neck of the femur is angled forward compared to the rest of the bone, causing a compensatory internal rotation of the leg.[6] As a result, all structures downstream of the hip including the thigh, knee, and foot will turn in toward mid-line.[6] Femoral anteversion is the most common cause of in toeing in children older than 3 years of age.[3][4] It is most commonly bilateral, affects females twice as much as males, and in some families can show a hereditary pattern.[3] This condition may progressively worsen from years 4 to 7, yet the majority of case still spontaneously resolve by 8 years of age.[4]

- W-Sitting and inability to sit cross-legged

- Intoeing gait

- Circumduction Gait (legs swing around one another)

- Frequent tripping and clumsiness

2. Diagnosis

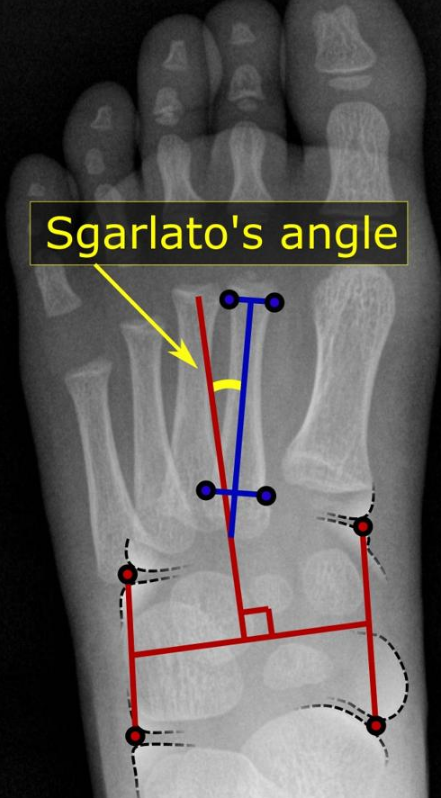

Pigeon toe can be diagnosed by physical examination alone.[8] This can classify the deformity into "flexible", when the foot can be straightened by hand, or otherwise "nonflexible".[8] Still, X-rays are often done in the case of nonflexible pigeon toe.[8] On X-ray, the severity of the condition can be measured with a "metatarsus adductus angle", which is the angle between the directions of the metatarsal bones, as compared to the lesser tarsus (the cuneiforms, the cuboid and the navicular bone).[9] Many variants of this measurement exist, but Sgarlato's angle has been found to at least have favorable correlation with other measurements.[10] Sgarlato's angle is defined as the angle between:[7][11]

- A line through the longitudinal axis of the second metatarsal bone.

- The longitudinal axis of the lesser tarsal bones. For this purpose, one line is drawn between the lateral limits of the fourth tarsometatarsal joint and the calcaneocuboid joint, and another line is drawn between the medial limits of the talonavicular joint and the 1st tarsometatarsal joint. The transverse axis is defined as going through the middle of those lines, and hence the longitudinal axis is perpendicular to this axis.

This angle is normally up to 15°, and an increased angle indicates pigeon toe.[7] Yet, it becomes more difficult to infer the locations of the joints in younger children due to incomplete ossification of the bones, especially when younger than 3–4 years.

Internal Tibial Torsion

Internal tibial torsion is diagnosed by physical exam.[4] The principle clinical exam is an assessment of the thigh-foot angle.[4] The affected individual is placed in prone position with the knees flexed to 90 degrees.[4] An imaginary line is drawn along the longitudinal axis of the thigh, and of the sole of the foot from a birds-eye view and the angle at the intersection of these two lines is measured.[4] A value greater than 10 degrees of internal rotation is considered internal tibial torsion.[4] A thigh-foot angle less than 10 degrees internal, and up to 30 degrees of external rotation is considered normal.[4]

Femoral Anteversion

Femoral anteversion is diagnosed by physical exam.[4] The principle physical exam maneuver is an assessment of hip mobility.[4] The child is evaluated in the prone position with knees flexed to 90 degrees.[4] Using the tibia as a lever arm the femur is rotated both internally and externally.[4] A positive exam demonstrates internal rotation of greater than 70 degrees and external rotation reduced to less than 20 degrees.[4] Normal values for internal rotation are between 20 and 60 degrees and normal values for external rotation are between 30 and 60 degrees.[4]

3. Treatment

In those less than eight years old with simple in-toeing and minor symptoms, no specific treatment is needed.[12]

Metatarsus Adductus

Nonoperative management: Non operative treatment of metatarsus adductus is dictated by the flexibility of the forefoot.[4] If the child can actively correct the forefoot to midline no treatment is indicated.[4] If the adduction cannot be corrected actively but is flexible in passive correction by an examiner, at-home stretching that mimics this maneuver can be performed by parents.[4] In the case of a rigid deformity serial casting can straighten the foot.[4]

Surgical Management: Most cases of metatarsus adductus that does not resolve is asymptomatic in adulthood and does not require surgery.[4] Occasionally, persistent rigid metatarsus adductus can produce difficulty and significant pain associated with inability to find accommodating footwear.[3] Surgical options include tasometatarsal capsulotomy with tendontransfers or tarsal osteotomies.[3] Due to the high failure rate of capsulotomy and tendon transfer it is generally avoided.[3][4] Osteotomy (cutting of bone) and realignment of the medial cuneiform, cuboid, or second through fourth metatarsal the safer and most effective surgery in patients over the age of 3 years old with residual rigid metatarsus adductus.[3]

Internal Tibial Torsion

Nonoperative management: There are no bracing, casting, or orthotic techniques that have been shown to impact resolution of tibial torsion.[3][4] This rotational limb variant does not increase risk for functional disability or higher rates of arthritis if unresolved.[4] Management involves parental education and observational visits to monitor for failure to resolve.[13]

Surgical management: Indications for surgical correction are a thigh foot angle greater tan 15 degrees in a child greater than 8 years of age that is experiencing functional limitations because of their condition.[4] Surgical correction is achieved most commonly through a tibial derotational osteotomy. This procedure involves the cutting (osteotomy) and straightening (derotation) of the tibia, followed by internal fixation to allow the bone to heal in place.[13]

Femoral Anteversion

Nonoperative management: Nonoperative treatment includes observation and parental education. Treatment modalities such as bracing, physical therapy, and sitting restrictions have not demonstrated any significant impact on the natural history of femoral anteversion.[4]

Surgical management: Operative treatment is reserved for children with significant functional or cosmetic difficulties due to residual femoral anteversion greater than 50 degrees or internal hip rotation greater than 80 degrees after age 8.[3][4] Surgical correction is achieved though a femoral derotation osteotomy.[6] This procedure involves the cutting (osteotomy) and straightening (derotation) of the femur, followed by internal fixation and to allow the bone to heal in place.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Medicine:Pigeon_toe

References

- "Intoeing". American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=a00055. "Reviewed by members of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America"

- Clifford R. Wheeless III, ed. "Internal Tibial Torsion". Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. http://www.wheelessonline.com/ortho/internal_tibial_torsion. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Todd, Lincoln (2003). "Common Rotational Variations in Children". Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 11 (5): 312–32–. doi:10.5435/00124635-200309000-00004. PMID 14565753. https://journals.lww.com/jaaos/Fulltext/2003/09000/Common_Rotational_Variations_in_Children.4.aspx.

- Rerucha, Caitlyn (2017). "Lower Extremity Abnormalities in Children". American Family Physician 96 (4): 226–233. PMID 28925669. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0815/p226.html.

- Farsetti, P (1994). "The long-term functional and radiographic outcomes of untreated and non-operatively treated metatarsus adductus". J Bone Joint Surg Am 76 (2): 257–265. doi:10.2106/00004623-199402000-00014. PMID 8113262. https://dx.doi.org/10.2106%2F00004623-199402000-00014

- "Femoral Anteversion" (in en). 8 August 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/femoral-anteversion.

- "A reappraisal of the relationship between metatarsus adductus and hallux valgus". Chin. Med. J. 127 (11): 2067–72. 2014. PMID 24890154. http://124.205.33.103:81/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?file_no=20130382&flag=1.

- "Metatarsus Adductus". http://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=metatarsus-adductus-90-P02770.

- Dawoodi, Aryan I.S.; Perera, Anthony (2012). "Reliability of metatarsus adductus angle and correlation with hallux valgus". Foot and Ankle Surgery 18 (3): 180–186. doi:10.1016/j.fas.2011.10.001. ISSN 1268-7731. PMID 22857959. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.fas.2011.10.001

- Michael Crawford, Donald Green. "METATARSUS ADDUCTUS: Radiographic and Pathomechanical Analysis". http://www.podiatryinstitute.com/pdfs/Update_2014/2014_05.pdf.

- Loh, Bryan; Chen, Jerry Yongqiang; Yew, Andy Khye Soon; Chong, Hwei Chi; Yeo, Malcolm Guan Hin; Tao, Peng; Koo, Kevin; Rikhraj Singh, Inderjeet (2015). "Prevalence of Metatarsus Adductus in Symptomatic Hallux Valgus and Its Influence on Functional Outcome". Foot & Ankle International 36 (11): 1316–1321. doi:10.1177/1071100715595618. ISSN 1071-1007. PMID 26202480. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F1071100715595618

- "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question". American Academy of Pediatrics-Section on Orthopaedics and the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America. http://www.choosingwisely.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/AAP_SO-POSNA-Choosing-Wisely-List.pdf.

- "Internal Tibial Torsion" (in en). 8 August 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/internal-tibial-torsion.