The histidine–aspartate (HD)-domain protein superfamily contains metalloproteins that share common structural features but catalyze vastly different reactions ranging from oxygenation to hydrolysis. This chemical diversion is afforded by (i) their ability to coordinate most biologically relevant transition metals in mono-, di-, and trinuclear configurations, (ii) sequence insertions or the addition of supernumerary ligands to their active sites, (iii) auxiliary substrate specificity residues vicinal to the catalytic site, (iv) additional protein domains that allosterically regulate their activities or have catalytic and sensory roles, and (v) their ability to work with protein partners. More than 500 structures of HD-domain proteins are available to date that lay out unique structural features which may be indicative of function. In this respect, we describe the three known classes of HD-domain proteins (hydrolases, oxygenases, and lyases) and identify their apparent traits with the aim to portray differences in the molecular details responsible for their functional divergence and reconcile existing notions that will help assign functions to yet-to-be characterized proteins.

- HD-domain

- metalloprotein

- oxygenase

- phosphatase

- phosphodiesterase

- hydratase

- nucleic acid

- phosphonate

- diiron

1. Introduction

The histidine–aspartate (HD)-domain superfamily [1] (IPR003607) contains more than 318,000 metalloproteins that are involved in a wide array of functions including immunoresponse [2], nucleic acid metabolism [3][4][5], inflammation [6], virulence [6][7][8], stress response [9][10], and small molecule activation [11][12][13]. They are found across all domains of life and are typified by a tandem histidine–aspartate (HD) dyad that coordinates at least one (often two or three) metal ions. Although there are many uncharacterized HD-domain proteins, chemical diversion appears to be linked to details in the local protein environment, extra ligands, and genomic co-occurrence with partner proteins, all of which may serve as blueprints for their functional assignment.

2. Characteristics and General Classification of HD-Domain Proteins

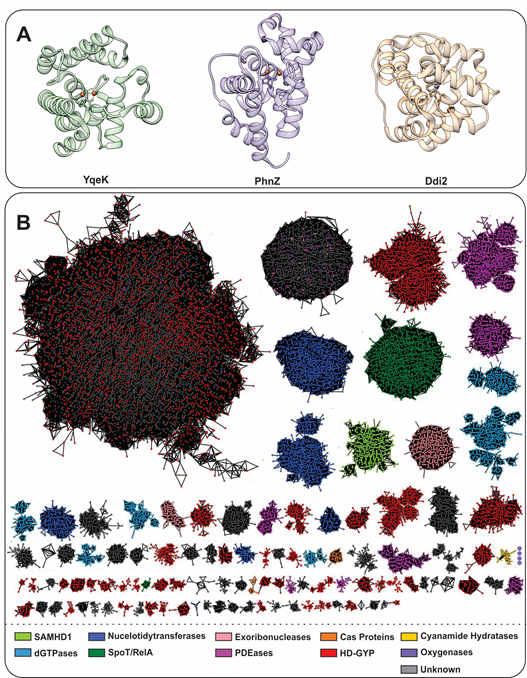

The main traits that functionally differentiate HD-domain proteins are (i) the chemical nature of the metal ion/cofactor, (ii) cofactor nuclearity, (iii) supernumerary ligands, (iv) conserved amino acid sequence motif insertions or residues vicinal to the active site, (v) auxiliary domains with catalytic or regulatory roles, and (vi) interaction with protein partners. These six features appear to distinctly influence the range of chemistries these proteins perform. Despite variations in primary sequence, all HD-domain proteins share the HD residue dyad that coordinates transition metal ions such as Fe, Mn, Co, Mg, Cu, Zn, and Ni (Table 1) as well as a helical fold (Figure 1a) and functionally cluster based on sequence similarities (Figure 1b) [14].

Table 1. List of representative histidine–aspartate (HD)-domain proteins from the three known subclasses, oxygenases, phosphatases and phosphodiesterases (PDEs), that are crystallographically and biochemically [15]characterized.

|

Subclasses |

Protein |

Nuclearity |

Active metal |

Chemistry |

Substrate |

PDB ID |

Origin |

References |

|

oxygenases |

MIOX |

dinuclear |

Fe |

Oxygenase |

myo-inositol |

2HUO |

Mus musculus |

[14] |

|

PhnZ |

dinuclear |

Fe |

Oxygenase |

OH-AEP |

4MLM |

bacterium HF130_AEPn_1 |

[15] |

|

|

TmpB |

dinuclear |

Fe |

Oxygenase |

OH-TMAEP |

6NPA |

Leisingera caerulea |

[13] |

|

|

phosphatases |

YfbR |

mononuclear |

Co |

Monophosphatase |

dAMP |

2PAQ |

Escherichia coli K-12 |

[3] |

|

YGK1 |

mononuclear |

Mn |

Monophosphatase |

dNMP |

5YOX |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

[5] |

|

|

YqeK |

dinuclear |

Fe |

Diphosphatase |

Ap4A |

2O08 |

Bacillus halodurans |

[10] |

|

|

YpgQ |

mononuclear |

Mn |

Diphosphatase |

dNTP |

5DQV |

Bacillus subtilis |

[16] |

|

|

SpoT |

mononuclear |

Mn |

Diphosphatase |

(p)ppGpp |

1VJ7 |

Streptococcus dysgalactiae |

[17] |

|

|

SAMHD1 |

mononuclear |

Mg |

Triphosphatase |

dNTP |

3U1N |

Homo sapiens |

||

|

EF1143 |

mononuclear |

Mg |

Triphosphatase |

dNTP |

4LRL |

Enterococcus faecalis V583 |

||

|

OxsA |

Mono/dinuclear* |

Co |

Mono/Di/ Triphosphatase |

Oxetanocin-A |

5TK8 |

Bacillus megaterium |

[22] |

|

|

phosphodiesterases |

Cas3 |

dinuclear |

Co |

PDE |

ssDNA |

4QQW |

Thermobifida fusca YX |

[23] |

|

Cas3 |

dinuclear |

Ni |

PDE |

ssDNA |

4Q2C |

Thermobaculum terrenum |

[24] |

|

|

Cas3’’ |

dinuclear |

Ca |

PDE |

ssDNA |

3S4L |

Methanocaldococcus jannaschii |

[25] |

|

|

Cas10 |

dinuclear |

Ni, Mn |

PDE |

ssDNA |

4W8Y |

Pyrococcus furiosus |

[26] |

|

|

PDE1-3 |

dinuclear# |

Mg, Mn |

PDE |

cAMP, cGMP |

1TAZ, 3ITU, 1SO2 |

Homo sapiens |

||

|

PDE4 |

dinuclear# |

Mg, Mn |

PDE |

cAMP |

1F0J |

Homo sapiens |

[29] |

|

|

PDE5 |

dinuclear# |

Mg |

PDE |

cGMP |

1TBF |

Homo sapiens |

[30] |

|

|

PDE7-8 |

dinuclear# |

Mn |

PDE |

cAMP |

4PM0, 3ECM |

Homo sapiens |

||

|

PDE9 |

dinuclear# |

Mn, Mg |

PDE |

cGMP |

3DY8 |

Homo sapiens |

[33] |

|

|

|

PDE10 |

dinuclear# |

Mg |

PDE |

cAMP, cGMP |

2OUN |

Homo sapiens |

[34] |

|

|

PgpH |

dinuclear |

Mn |

PDE |

c-di-AMP |

4S1B |

Listeria monocytogenes |

[6] |

|

|

Bd1817 |

dinuclear |

Fe* |

PDE |

c-di-GMP |

3TM8 |

Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus |

[35] |

|

|

PmGH |

trinuclear |

Fe, Mn |

PDE |

c-di-GMP |

4MCW |

Persephonella marina EX-H1 |

[36] |

|

|

PA4781 |

trinuclear& |

Mg |

PDE |

c-di-GMP |

4R8Z |

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 |

[14] |

|

lyases |

Ddi2 |

mononuclear |

Zn |

Hydratase |

Cyanamide |

6DKA |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae |

[37] |

# denotes proteins for which the crystal structure shows two active site metal ions at an average interatomic distance of ≈3.8 Å. The primary sequence suggests a mononuclear binding site. In phosphodiesterases (PDEs), the second metal ion is stabilized by the aspartate of the HD motif, a bridging hydroxide and four terminally ligated water molecules. & Although no experimental evidence currently exists, PA4781 belongs the trinuclear clade of HD-GYP proteins as inferred from its primary amino acid sequence. * Bd1817 is inactive toward Bis-(3'-5')-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP); therefore, the active metal ion refers to the metal ion observed in the crystal structure. OH-AEP stands for 1-hydroxy-2-aminoethylphosphonate, OH-TMAEP stands for 1-hydroxy-2-(trimethylammonio)ethylphosphonate, dNMP stands for deoxymonophosphate, in which N can be A, G, U, C, Ap4A stands for diadenosine tetraphosphate, cGMP stands for guanosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate, cAMP stands for adenosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate, c-di-AMP stands for Bis-(3'-5')-cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

Figure 1. (A). Helical structure of three HD-domain proteins. YqeK (PDB: 2O08) is a phosphatase, PhnZ (PDB: 4N6W) is an oxygenase, and Ddi2 (PDB: 6DKA) is a lyase. All exhibit a helical fold characteristic to HD-domain proteins despite their diverse functions. (B). Sequence similarity network (SSN) of the HD-domain superfamily depicting its size and functional clustering. The SSN was generated via the Enzyme Function Initiatives-Enzyme Similarity tool (EFI-EST) and visualized in Cytoscape. The SSN was generated by employing the IPR003697 family and tailored so that nodes represent sequences with ≥ 50% identity and an e-value of 5. The SSN was further refined to contain the major protein clusters (size-wise), which amount to 183,015 unique protein sequences. Edges between nodes represent an alignment score of 70. HD-domain phosphohydrolases (SpoT/RelA, SAMHD1, deoxyguanosine phosphatases (dGTPases), nucleotidyltransferases) are represented in green and blue, while hydratases are shown in yellow. PDEs are shown in red (HD-GYP proteins), light pink (exoribonucleases), orange (Cas proteins), and pink (PDEases). Oxygenases are shown in purple and their cluster, which consists of four nodes (372 sequences), is enlarged for visualization. Gray clusters contain proteins of unidentified function.

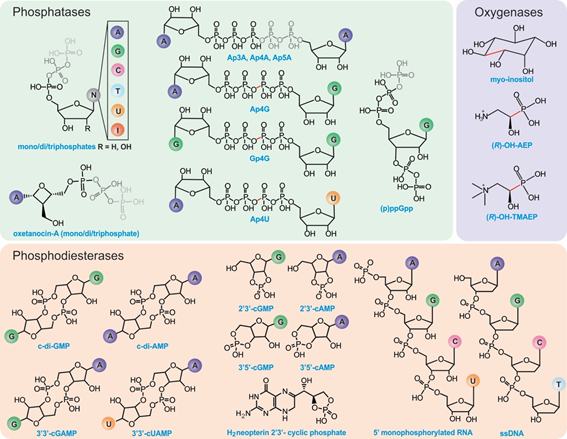

The HD-domain superfamily fosters three different enzymatic classes: hydrolases, oxygenases, and lyases, with the hydrolases being the largest and best-characterized group. Hydrolases are further subdivided into (i) phosphatases, including dGTPases [38], RelA/SpoT, SAMHD1, EF1143, etc. and (ii) phosphodiesterases (PDEs), including exoribonucleases [39], PDEases, Cas proteins, and HD-GYPs[40] (Figure 1b). Phosphatases hydrolyze a multitude of (deoxy)nucleotide-based substrates that vary in the identity of their base(s) and the extent of phosphorylation (Figure 2) . PDEs, on the other hand, degrade a variety of cyclic signaling molecules and single-stranded nucleic acids (Figure 2) [41]. Oxygenases and lyases are relatively recent additions to the HD-domain superfamily with only a handful of representatives to have been biochemically characterized. All identified oxygenases catalyze the oxidative cleavage of C-C/P bonds (Figure 2), while the single known lyase is a cyanamide hydratase. This functional plurality widens the chemical repertoire of the HD-domain superfamily, which is likely to harbor more oxygenases, lyases, or enzymes with novel chemistries.

Figure 2. Known substrates of HD-domain proteins. Phosphatases can remove one to three terminal phosphate groups from (deoxy)ribonucleotides or cleave (a)symmetrically polyphosphate containing nucleotides (represented in gray). The position of cleavage has been highlighted in red for substrates with four phosphates. PDEs hydrolyze phosphodiester bonds of cyclic (di)nucleotide substrates via either one-step hydrolysis (cleavage of one side of the diester bond) releasing a linearized product or two-step hydrolysis releasing individual nucleotides. PDEs can also act on RNA and DNA substrates. HD-domain oxygenases oxidatively cleave a C-X bond (indicated in red).

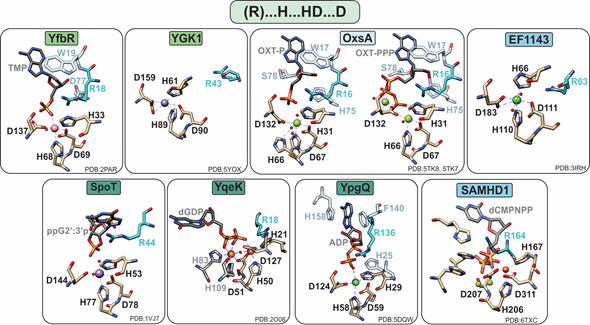

3. HD-Domain Hydrolases: The Phosphatase Subfamily

HD-domain phosphatases play essential roles in regulating the cellular pool of (deoxy)ribonucleotides and signaling molecules involved in bacterial stress responses [42], such as (p)ppGpp and Ap4A (Figure 2). Phosphatases are further subdivided into mono-, di-, and triphosphatases with distinct structural features that may provide clues for the future classification of unknown HD-domain phosphatases. Interestingly, all have a strictly conserved arginine residue prior to the first histidine of the metal binding motif (Figure 3), which is pivotal for activity. The exact chemical role of this arginine in catalysis has not yet been delineated. Its importance in hydrolysis most likely stems from the ability of this residue to ensure proper substrate positioning and/or to form intermolecular interactions with the substrate phosphate groups. Most biochemically characterized HD-domain mono- and diphosphatases are dimers in solution , which appears to be related to enzymatic function and may represent a regulatory mechanism for tuning activity. However, it is currently unknown if both sites are catalytically active or if one site allosterically activates the other. In contrast, triphosphatases are allosterically regulated by nucleotide binding to secondary sites, and most are active as tetramers or hexamers.

Figure 3. Active sites of HD-domain phosphohydrolases. Mononuclear HD-domain phosphohydrolases utilize a conserved motif “H.HD…D” to bind a variety of metals including cobalt (pink), zinc (purple), magnesium (light green), nickel (dark green), or iron (orange). Small red spheres represent water molecules. The dinuclear phosphatase YqeK harbors two extra histidines between the HD and D residues to stabilize the second metal ion. Phosphatases are classified into mono-, di-, or triphosphohydrolases, labeled in light green, dark green, and blue, respectively. All phosphohydrolases have a conserved arginine (shown in teal), which is located typically three residues prior to the first histidine of the HD motif and in the vicinity of the oxygens of the substrate phosphate group. Other important residues are shown in pale blue and are described in the text.

In most cases, phosphate hydrolysis is supported by non-redox metal ions, with the most active cofactors being Co or Mn for monophosphatases, Mn for diphosphatases, and Mg or Mn for triphosphatases (Table 1). With a few notable exceptions (YqeK, SAMHD1, and OxsA), these metals are bound in a mononuclear configuration by a conserved “H…HD…D” motif (Figure 3).

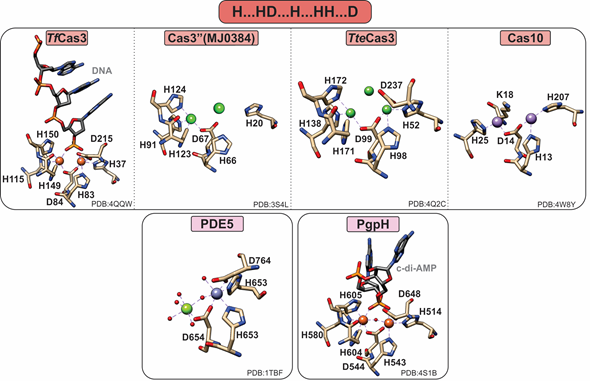

4. HD-Domain Hydrolases: The PDE Subfamily

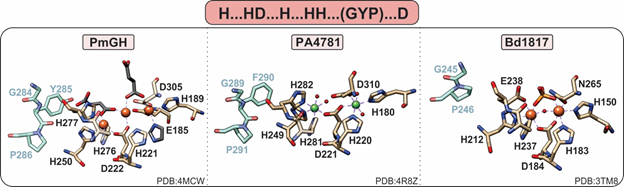

PDEs can harbor both mononuclear and polynuclear cofactors. A common feature of all known polynuclear (di-or trinuclear) PDEs is an extra histidine residue in the active site such that their characteristic metal binding sequence is “H…HD…H…HH…D” (Figure 4). The role of this histidine in activity or structure has not been explicitly established. However, on the basis of structural studies, this residue makes additional hydrogen bond contacts to the substrate phosphate groups, suggesting a possible role in substrate binding.

Figure 4. Active sites of HD-domain PDEs. HD-domain PDEs utilize the conserved HD motif “H…HD…H.HH.D” to bind a di- or trinuclear metal center. The metal ions coordinated in their active sites are zinc (purple), magnesium (light green), nickel (dark green), or iron (orange). Small red spheres represent water molecules.

4.1. HD-Domain PDEs Acting on DNA and RNA

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-associated systems (Cas) are major players in prokaryotic adaptive immunity and RNA-based defense [50][51]. Type I CRISPR–Cas utilize a multicomponent system and recruit a single nuclease, Cas3, for the degradation of invader nucleic acids. The Cas3-associated gene can encode for a protein that has only the HD-domain (Cas3′’, I-A subtype), or more commonly, an N-terminal HD-domain fused to a Superfamily 2 helicase (Cas3). Type III-B CRISPR–Cas utilize Cas10 (Cmr2) for RNA-activated ssDNA cleavage.

The crystal structure of the Thermobifida fusca Cas3 shows a diiron active site (Figure 4), yet no activity with this cofactor has been demonstrated . Cas3 proteins can be promiscuously activated by various metal ions, with most being activated by Ni or Co and, to a lesser extent, by other divalent metal ions (with the exception of Mg and Ca). In contrast, the Pyrococcus furiosus Cmr2 (dinuclear) and the Cas3′’ proteins (mononuclear in the published structures) exhibit an Mg-dependent PDE activity [23,25]. The nuclearity of the Cas3′’s may be an artifact due to the larger flexibility of the protein polypeptide, making binding of the second metal ion more transient. Of note, no correlation between helicase and PDE activities has been demonstrated to date.

4.2. HD-Domain PDEs Acting on Cyclic Mononucleotides

cAMP- and cGMP-specific PDEs (also referred to as PDEases) are essential regulators in cyclic nucleotide-dependent signal transduction in diverse physiological processes including immune response, neuronal activity, hypertension, and inflammatory response [52]. Currently, 21 genes encoding human PDEases have been identified and classified into 12 families according to their substrate specificities, pharmacological properties, and tissue localization [53]. These are further divided into three groups: cAMP-specific (PDE4, PDE7, PDE8, and PDE12), cGMP-specific (PDE5, PDE6, and PDE9) , and dual-specific (PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, PDE10, and PDE11).

All PDEases are dimeric and have a conserved catalytic carboxy terminal domain as well as a variable regulatory amino terminal domain [54]. However, PDEases are also active as monomers; therefore, the functional significance of dimerization remains unknown [54]. On the basis of their binding affinity for divalent metal ions, PDEases are distinguished into two classes: Class I in mammals and flies and Class II in yeast and protozoans [55]. The most extensively studied are Class I PDEases, in which two metal ions (e.g., Zn and Mg) are octahedrally coordinated, forming a somewhat unconventional bimetallic site Although the canonical motif suggests the binding of a single metal ion (M1) in the HD motif, stabilization of the second metal ion (M2) is accomplished via the aspartate of the HD motif and five water molecules, one of which is bridging M1 and M2. The bridging water molecule has been suggested to be a hydroxide, which can nucleophilically attack the phosphodiester bond . In the crystal structures, the identity of M1 and M2 is often found to be Zn2+ and Mg2+, respectively (Figure 4) . Class I PDEs are active with either Mn or Mg but not with Zn. Therefore, although Zn can bind in the M1 position with high affinity, it cannot stimulate activity by itself or has inhibitory effects.

The substrate specificity in PDEases is afforded by a so-called “glutamine-switch” mechanism in which a conserved glutamine in the vicinity of the active site can adopt two different orientations. In one orientation, it can form a bidentate hydrogen bond with the adenine ring (cAMP-specific) or two hydrogen bonds with guanine ring and two hydrogen bonds with neighboring alanine and tryptophan residues (cGMP-specific) [30,31]. In the dual-specific PDEases, the conserved glutamine has higher rotational flexibility and no orientation constraints, allowing it to adopt orientations for both substrates.

4.3. HD-Domain PDEs Acting on c-di-AMP

Cyclic-di-AMP is a second messenger essential in bacterial signaling and a critical player in bacterial physiology and pathogenesis [56][57]. PgpH performs the one-step hydrolysis of c-di-AMP to 5′pApA in an Mn-dependent fashion but cannot hydrolyze other cyclic dinucleotides (i.e., c-di-GMP). The active site Mn2+ ions are octahedrally coordinated by seven residues, H514, H543, D544, H580, H604, H605, and D648, as well as the two terminal oxygen atoms of the c-di-AMP phosphate group (Figure 4). The metal ions activate a water molecule opposite the scissile phosphate for the nucleophilic attack of phosphorus. Protonation of the resulting oxyanion terminates the reaction.

4.4. HD-Domain PDEs Acting on c-di-GMP and c-GAMP; the HD-GYP Subclass

HD-GYPs are a special subclass of the PDE subfamily and are functionally homologous to EAL proteins (typified by the glutamate-alanine-leucine residue triad) [58]. They can be single domain proteins or fusions to extra regulatory, sensory, or catalytic protein domains [59][60].

While cyclic-di-GMP is their most common substrate, the recently discovered hybrid dinucleotide, 3′3′c-GAMP, is also hydrolyzed by some HD-GYPs [59]. Out of the nine HD-GYPs encoded in Vibrio cholerae, VCA0681, VCA0931, and VCA0210 are the only HD-GYPs to hydrolyze both c-di-GMP and 3′3′c-GAMP. More recently, PmxA from Myxococcus xanthus was identified as a 3′3′c-GAMP specific PDE that is hardly active toward c-di-GMP or c-di-AMP [60]. Selectivity for 3′3′c-GAMP is attributed to a glutamine near the active site, although this residue is not conserved in VCA0681, VCA0931, and VCA0210, suggesting that the molecular origins for 3′3′cGAMP specificity may vary among HD-GYPs.

In addition to the seventh ligand added to their active site (i.e., an extra histidine adjacent to the last histidine of the motif), all active HD-GYPs have a glycine-tyrosine-proline (GYP) residue triad in a loop close to the active site (Figure 5) [35]. However, because single amino acid substitutions of each of the GYP domain residues to alanines hardly affect PDE activity [36], its role in catalysis and protein stability remains poorly understood. The GYP motif is considered important for interaction with the GGDEF cyclase (named after its highly conserved Gly-Gly-Asp-Glu-Phe sequence motif) [8] and serves as a substrate specificity element for the recognition of c-di-GMP and its hybrid 3′3′-cGAMP analog [40].

Figure 5. Active site of HD-GYPs. HD-GYP proteins utilize an “H…HD…H…HH…D” motif that typically binds a dinuclear metal center. The third metal ion in the PmGH active site is stabilized by crystallization molecules shown in gray. In addition, these enzymes contain a GYP residue triad vicinal to the active site (shown in blue), the importance of which is currently unclear. Bd1817, which is inactive toward c-di-GMP, lacks the GYP tyrosine and the terminal aspartate is an asparagine.

HD-GYPs differ on the basis of their active metal cofactor and possible catalytic outcomes. While most commonly harbor a dimetal cofactor, some incorporate a trinuclear cofactor by involving a glutamate residue as an eighth ligand to the site (Figure 5) [36]. The assembly of a dinuclear or trinuclear cofactor is presumed to afford different reaction outcomes. Dinuclear HD-GYPs can only perform a one-step hydrolysis, whereas trinuclear ones can perform a two-step hydrolysis, leading to the respective monophosphates. Metal ions that can stimulate hydrolysis are Fe, Mn, and, to a lesser extent, Co and Ni [40].

PmGH from Persephonella marina is the prototypical trinuclear HD-GYP and the first to be crystallographically characterized [36]. PmGH harbors a triiron cofactor with the third iron coordinated by the glutamate E185. The trimetal cofactor is additionally stabilized by three other crystallization molecules, invoking the possibility that other solvent molecules may be incorporated under physiological conditions (Figure 5). It is active with both Fe2+ and Mn2+. On the basis of primary amino acid sequence, PA4781 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa is also a putative trinuclear PDE; however, the available crystal structure shows two Ni ions in the active site at an elongated distance. PA4781 is unselective in its metal ion incorporation, has limited activity, and exhibits a preference for 5′-pGpG over c-di-GMP to form GMPs [14].

Only one structure of a dinuclear HD-GYP exists: Bd1817 from Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus. It harbors a diiron cofactor, but the presence of an asparagine instead of the last aspartate of the binding motif, a degraded GYP motif (Figure 5), and its complete inactivity toward c-di-GMP [35] do not allow for the inference of substrate positioning and specificity in dinuclear HD-GYPs.

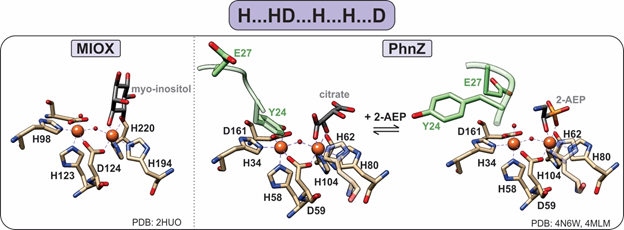

5. HD-Domain Oxygenases

Most of the known HD-domain proteins are phosphohydrolases, but three members, namely myo-inositol oxygenase (MIOX), PhnZ, and TmpB, are monooxygenases and perform the oxidative cleavage of a C-X bond [11][12][13][15]. The discovery of this chemistry expands the catalytic repertoire of the HD-domain superfamily, and their conserved protein features may provide insight into the identification of yet-to-be-characterized HD-domain proteins as oxygenases.

The first discovered HD-domain oxygenase, MIOX, catalyzes the oxidative cleavage of a C-C bond of myo-inositol to form D-glucuronic acid (Figure 6) . Myo-inositol is a precursor for inositol phosphoglycans, which act as insulin mediators, and altered inositol metabolism has been associated with diabetes. Therefore, the activity of MIOX is of increasing interest, as it presents a potential therapeutic target for treating both type-1 and type-2 diabetes.

Figure 6. Active sites of HD-domain oxygenases. Oxygenases utilize the “H…HD…H…H…D” motif to bind a diiron metal center. The substrate scissile bond is positioned above one of the iron sites, leaving the second site open for oxygen binding. PhnZ and TmpB contain an YxxE loop (green) in their primary sequence that is located vicinal to the active site, which upon substrate binding undergoes a conformational change to allow for oxygen binding and catalysis.

PhnZ and TmpB were later established as oxygenases, demonstrating that MIOX is not a functional outlier [12][13]. Both PhnZ and TmpB are involved in the degradation of organophosphonates, which are compounds that serve as sources of inorganic phosphate for bacteria that occupy phosphate-limited environments (e.g., marine ecosystems) [12]. Unlike MIOX, PhnZ and TmpB act in tandem with the non-heme α-ketoglutarate (KG) dependent hydroxylases PhnY and TmpA, respectively, to cleave the C–P bond of their substrates (Figure 2) [12][13]. PhnY initiates the degradation of 2-aminoethylphosphonate (2-AEP) via the addition of a hydroxyl group to the C1 carbon in a stereospecific manner producing (R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyethyl phosphonate (OH-AEP) [12]. PhnZ performs the subsequent oxidative cleavage of the C-P bond of OH-AEP forming inorganic phosphate and glycine (Figures 2 and 6) [12]. The TmpA/TmpB pathway is mechanistically similar, with the only difference being the nature of the substrate, i.e., 2-(trimethylammonio)ethyl phosphonate (TMAEP) for TmpA[13].

MIOX, PhnZ, and TmpB bind a catalytically essential diiron cofactor via the HD-domain sequence “H…HD…H…H…D” (Figure 6). Each iron is coordinated in an octahedral geometry and bridged by the carboxylate group of the first aspartate residue in the HD-domain sequence as well as a μ-oxo/hydroxo bridge (Figure 6) [15]. Unlike other dinuclear nonheme–iron oxygenases, which utilize the fully reduced FeII/FeII form of their cofactors, HD-domain oxygenases stabilize a mixed-valent FeII/FeIII state for the four-electron oxidation of a C-C/P bond and do not require an external reducing system for reactivation of the cofactor (i.e., after one substrate turnover the site returns to the FeII-FeIII form) [15]. Stabilization under the same redox conditions of the FeIIFeIII cofactor in oxygenases and the FeIIFeII cofactor in HD-domain hydrolases suggests that the HD-domain sites may tune activity through the modulation of cofactor reduction potentials.

The iron ion in the Fe1 site serves as a Lewis acid and binds the substrate such that the C-X bond is opposite the iron (Figure 6) [15]. Then, the second iron site (Fe2) is available to bind molecular oxygen, forming a FeIII/FeIII superoxo species that initiates oxidative cleavage by abstracting a hydrogen atom from the substrate. Following turnover, the active mixed-valent FeII/FeIII form is regenerated , and thus, there is no need for an external reducing system to reactivate the enzyme, which is a feature unique to HD-domain containing oxygenases.

Unlike MIOX, PhnZ and TmpB sequences contain a transient YxxE loop involved in substrate binding. Prior to substrate binding, the tyrosine (Y24 in PhnZ and Y30 in TmpB) is oriented toward the active site and binds to the Fe2 site, while the glutamate (E27 in PhnZ and E33 in TmpB) faces away from the active site [13][15]. Substrate binding induces a conformational change, positioning the glutamate within hydrogen bonding distance to the amino group of the substrate and causing the tyrosine–iron bond to break [13][15]. Dissociation of the tyrosine frees the Fe2 site for O2 binding and subsequent turnover and most likely serves as a protective mechanism to prevent oxidative inactivation of the active site (Figure 6).

Collectively, HD-domain oxygenases have catalytic and structural features that differ significantly not only from that of other nonheme–iron oxygenases, but also of HD-domain hydrolases. This divergence is useful as it can provide some descriptors to distinguish oxygenases from hydrolases within the HD-domain family. It is likely that these characteristics are conserved among all HD-domain oxygenases and may provide a critical first step into the characterization of other HD-domain proteins of unknown function.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/catal10101191

References

- Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 469–472.

- Chen, S.; Bonifati, S.; Qin, Z.; St Gelais, C.; Wu, L. SAMHD1 Suppression of Antiviral Immune Responses. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 27, 254–267.

- Zimmerman, M.D.; Proudfoot, M.; Yakunin, A.; Minor, W. Structural Insight into the Mechanism of Substrate Specificity and Catalytic Activity of an HD-Domain Phosphohydrolase: The 5′-Deoxyribonucleotidase YfbR from Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 378, 215–226.

- Ji, X.; Tang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Xiong, Y. Structural basis of cellular dNTP regulation by SAMHD1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E4305–E4314.

- Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Yang, D.; Zhou, K.; Liu, M.; Gao, Z.; Liu, P.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q. Structural and biochemical characterization of the yeast HD domain containing protein YGK1 reveals a metal-dependent nucleoside 5ʹ-monophosphatase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 674–681.

- Huynh, T.; Luo, S.; Pensinger, D.; Sauer, J.-D.; Tong, L.; Woodward, J. An HD-domain phosphodiesterase mediates cooperative hydrolysis of c-di-AMP to affect bacterial growth and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E747–E756.

- Dow, J.M.; Fouhy, Y.; Lucey, J.F.; Ryan, R.P. The HD-GYP Domain, Cyclic Di-GMP Signaling, and Bacterial Virulence to Plants. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2006, 19, 1378–1384.

- Ryan, R.P.; McCarthy, Y.; Andrade, M.; Farah, C.S.; Armitage, J.P.; Dow, J.M. Cell-cell signal-dependent dynamic interactions between HD-GYP and GGDEF domain proteins mediate virulence in Xanthomonas campestris. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5989–5994.

- Atkinson, G.C.; Tenson, T.; Hauryliuk, V. The RelA/SpoT Homolog (RSH) Superfamily: Distribution and Functional Evolution of ppGpp Synthetases and Hydrolases across the Tree of Life. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23479.

- Minazzato, G.; Gasparrini, M.; Amici, A.; Cianci, M.; Mazzola, F.; Orsomando, G.; Sorci, L.; Raffaelli, N. Functional Characterization of COG1713 (YqeK) as a Novel Diadenosine Tetraphosphate Hydrolase Family. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202, e00053-20.

- Brown, P.M.; Caradoc-Davies, T.T.; Dickson, J.M.J.; Cooper, G.J.S.; Loomes, K.M.; Baker, E.N. Crystal structure of a substrate complex of myo-inositol oxygenase, a di-iron oxygenase with a key role in inositol metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 15032–15037.

- Wörsdörfer, B.; Lingaraju, M.; Yennawar, N.H.; Boal, A.K.; Krebs, C.; Bollinger, J.M.; Pandelia, M.-E. Organophosphonate-degrading PhnZ reveals an emerging family of HD domain mixed-valent diiron oxygenases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18874–18879.

- Rajakovich, L.J.; Pandelia, M.-E.; Mitchell, A.J.; Chang, W.-C.; Zhang, B.; Boal, A.K.; Krebs, C.; Bollinger, J.M. A New Microbial Pathway for Organophosphonate Degradation Catalyzed by Two Previously Misannotated Non-Heme-Iron Oxygenases. Biochemistry 2019, 58, 1627–1647.

- Rinaldo, S.; Paiardini, A.; Stelitano, V.; Brunotti, P.; Cervoni, L.; Fernicola, S.; Protano, C.; Vitali, M.; Cutruzzolà, F.; Giardina, G. Structural Basis of Functional Diversification of the HD-GYP Domain Revealed by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA4781 Protein, Which Displays an Unselective Bimetallic Binding Site. J. Bacteriol. 2015, 197, 1525–1535.

- van Staalduinen, L.M.; McSorley, F.R.; Schiessl, K.; Séguin, J.; Wyatt, P.B.; Hammerschmidt, F.; Zechel, D.L.; Jia, Z. Crystal structure of PhnZ in complex with substrate reveals a di-iron oxygenase mechanism for catabolism of organophosphonates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5171–5176.

- Jeon, Y.J.; Park, S.C.; Song, W.S.; Kim, O.-H.; Oh, B.-C.; Yoon, S.-I. Structural and biochemical characterization of bacterial YpgQ protein reveals a metal-dependent nucleotide pyrophosphohydrolase. J. Struct. Biol. 2016, 195, 113–122.

- Hogg, T.; Mechold, U.; Malke, H.; Cashel, M.; Hilgenfeld, R. Conformational antagonism between opposing active sites in a bifunctional RelA/SpoT homolog modulates (p)ppGpp metabolism during the stringent response Cell 2004, 117, 57–68.

- Goldstone, D.C.; Ennis-Adeniran, V.; Hedden, J.J.; Groom, H.C.; Rice, G.I.; Christodoulou, E.; Walker, P.A.; Kelly, G.; Haire, L.F.; Yap, M.W.; et al. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature 2011, 480, 379–382.

- Morris, E.R.; Caswell, S.J.; Kunzelmann, S.; Arnold, L.H.; Purkiss, A.G.; Kelly, G.; Taylor, I.A. Crystal structures of SAMHD1 inhibitor complexes reveal the mechanism of water-mediated dNTP hydrolysis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3165.

- Vorontsov, I.I.; Minasov, G.; Kiryukhina, O.; Brunzelle, J.S.; Shuvalova, L.; Anderson, W.F. Characterization of the deoxynucleotide triphosphate triphosphohydrolase (dNTPase) activity of the EF1143 protein from Enterococcus faecalis and crystal structure of the activator-substrate complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 33158–33166.

- Vorontsov, I.I.; Wu, Y.; DeLucia, M.; Minasov, G.; Mehrens, J.; Shuvalova, L.; Anderson, W.F.; Ahn, J. Mechanisms of Allosteric Activation and Inhibition of the Deoxyribonucleoside Triphosphate Triphosphohydrolase from Enterococcus faecalis. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 2815–2824.

- Bridwell-Rabb, J.; Kang, G.; Zhong, A.; Liu, H.-w.; Drennan, C.L. An HD domain phosphohydrolase active site tailored for oxetanocin-A biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13750–13755.

- Huo, Y.; Nam, K.H.; Ding, F.; Lee, H.; Wu, L.; Xiao, Y.; Farchione, M.D.; Zhou, S.; Rajashankar, K.; Kurinov, I.; Zhang, R.; Ke, A. Structures of CRISPR Cas3 offer mechanistic insights into Cascade-activated DNA unwinding and degradation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 771–777.

- Gong, B.; Shin, M.; Sun, J.; Jung, C.H.; Bolt, E.L.; van der Oost, J.; Kim, J.S. Molecular insights into DNA interference by CRISPR-associated nuclease-helicase Cas3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16359–16364.

- Beloglazova, N.; Petit, P.; Flick, R.; Brown, G.; Savchenko, A.; Yakunin, A.F. Structure and activity of the Cas3 HD nuclease MJ0384, an effector enzyme of the CRISPR interference. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 4616–4627.

- Benda, C.; Ebert, J.; Scheltema, R.A.; Schiller, H.B.; Baumgärtner, M.; Bonneau, F.; Mann, M.; Conti, E. Structural Model of a CRISPR RNA-Silencing Complex Reveals the RNA-Target Cleavage Activity in Cmr4. Mol. Cell 2014, 56, 43–54.

- Pandit, J.; Forman, M.D.; Fennell, K.F.; Dillman, K.S.; Menniti, F.S. Mechanism for the allosteric regulation of phosphodiesterase 2A deduced from the X-ray structure of a near full-length construct. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 18225–18230.

- Scapin, G.; Patel, S.B.; Chung, C.; Varnerin, J.P.; Edmondson, S.D.; Mastracchio, A.; Parmee, E.R.; Singh, S.B.; Becker, J.W.; Van der Ploeg, L.H.T.; et al. Crystal Structure of Human Phosphodiesterase 3B: Atomic Basis for Substrate and Inhibitor Specificity. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6091–6100.

- Xu, R.X.; Hassell, A.M.; Vanderwall, D.; Lambert, M.H.; Holmes, W.D.; Luther, M.A.; Rocque, W.J.; Milburn, M.V.; Zhao, Y.; Ke, H.; et al. Atomic Structure of PDE4: Insights into Phosphodiesterase Mechanism and Specificity. Science 2000, 288, 1822–1825.

- Zhang, K.Y.J.; Card, G.L.; Suzuki, Y.; Artis, D.R.; Fong, D.; Gillette, S.; Hsieh, D.; Neiman, J.; West, B.L.; Zhang, C.; et al. A glutamine switch mechanism for nucleotide selectivity by phosphodiesterases. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 279–286.

- Kawai, K.; Endo, Y.; Asano, T.; Amano, S.; Sawada, K.; Ueo, N.; Takahashi, N.; Sonoda, Y.; Nagai, M.; Kamei, N.; et al. Discovery of 2-(cyclopentylamino)thieno [3,2-d]pyrimidin-4(3H)-one derivatives as a new series of potent phosphodiesterase 7 inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 9844–9854.

- Wang, H.; Yan, Z.; Yang, S.; Cai, J.; Robinson, H.; Ke, H. Kinetic and Structural Studies of Phosphodiesterase-8A and Implication on the Inhibitor Selectivity. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 12760–12768.

- Liu, S.; Mansour, M.N.; Dillman, K.S.; Perez, J.R.; Danley, D.E.; Aeed, P.A.; Simons, S.P.; LeMotte, P.K.; Menniti, F.S. Structural basis for the catalytic mechanism of human phosphodiesterase 9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13309–13314.

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Hou, J.; Zheng, M.; Robinson, H.; Ke, H. Structural insight into substrate specificity of phosphodiesterase 10. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5782–5787.

- Lovering, A.L.; Capeness, M.J.; Lambert, C.; Hobley, L.; Sockett, R.E. The Structure of an Unconventional HD-GYP Protein from Bdellovibrio Reveals the Roles of Conserved Residues in this Class of Cyclic-di-GMP Phosphodiesterases. mBio 2011, 2, e00163-11.

- Bellini, D.; Caly, D.L.; McCarthy, Y.; Bumann, M.; An, S.-Q.; Dow, J.M.; Ryan, R.P.; Walsh, M.A. Crystal structure of an HD-GYP domain cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase reveals an enzyme with a novel trinuclear catalytic iron centre. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 26–38.

- Li, J.; Jia, Y.; Lin, A.; Hanna, M.; Chelico, L.; Xiao, W.; Moore, S.A. Structure of Ddi2, a highly inducible detoxifying metalloenzyme from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 10674–10685.

- Barnes, C.O.; Wu, Y.; Song, J.; Lin, G.; Baxter, E.L.; Brewster, A.S.; Nagarajan, V.; Holmes, A.; Soltis, S.M.; Sauter, N.K.; et al. The crystal structure of dGTPase reveals the molecular basis of dGTP selectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9333–9339.

- Oussenko, I.A.; Sanchez, R.; Bechhofer, D.H. Bacillus subtilis YhaM, a member of a new family of 3′-to-5′ exonucleases in gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 6250–6259.

- Sun, S.; Pandelia, M.-E. HD-[HD-GYP] Phosphodiesterases: Activities and Evolutionary Diversification within the HD-GYP Family. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2340–2350.

- Biswas, K.H.; Sopory, S.; Visweswariah, S.S. The GAF Domain of the cGMP-Binding, cGMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase (PDE5) Is a Sensor and a Sink for cGMP. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 3534–3543.

- Hauryliuk, V.; Atkinson, G.C.; Murakami, K.S.; Tenson, T.; Gerdes, K. Recent functional insights into the role of (p)ppGpp in bacterial physiology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 298–309.

- Ji, X.; Zou, J.; Peng, H.; Stolle, A.-S.; Xie, R.; Zhang, H.; Peng, B.; Mekalanos, J.J.; Zheng, J. Alarmone Ap4A is elevated by aminoglycoside antibiotics and enhances their bactericidal activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 9578–9585.

- Neidhardt, F.C. (Ed.) The Stringent Response. In Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 1458–1496.

- Xiao, H.; Kalman, M.; Ikehara, K.; Zemel, S.; Glaser, G.; Cashel, M. Residual guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate synthetic activity of relA null mutants can be eliminated by spoT null mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 5980–5990.

- Mauney, C.H.; Hollis, T. SAMHD1: Recurring roles in cell cycle, viral restriction, cancer, and innate immunity. Autoimmunity 2018, 51, 96–110.

- Ji, X.; Wu, Y.; Yan, J.; Mehrens, J.; Yang, H.; DeLucia, M.; Hao, C.; Gronenborn, A.M.; Skowronski, J.; Ahn, J.; et al. Mechanism of allosteric activation of SAMHD1 by dGTP. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013, 20, 1304–1309.

- Hollenbaugh, J.A.; Shelton, J.; Tao, S.; Amiralaei, S.; Liu, P.; Lu, X.; Goetze, R.W.; Zhou, L.; Nettles, J.H.; Schinazi, R.F.; et al. Substrates and Inhibitors of SAMHD1. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169052.

- Hansen, E.C.; Seamon, K.J.; Cravens, S.L.; Stivers, J.T. GTP activator and dNTP substrates of HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 generate a long-lived activated state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E1843–E1851.

- Morisaka, H.; Yoshimi, K.; Okuzaki, Y.; Gee, P.; Kunihiro, Y.; Sonpho, E.; Xu, H.; Sasakawa, N.; Naito, Y.; Nakada, S.; et al. CRISPR-Cas3 induces broad and unidirectional genome editing in human cells. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5302.

- Pickar-Oliver, A.; Gersbach, C.A. The next generation of CRISPR–Cas technologies and applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 490–507.

- Boswell-Smith, V.; Spina, D.; Page, C.P. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147, S252–S257.

- Eskandari, N.; Mirmosayyeb, O.; Bordbari, G.; Bastan, R.; Yousefi, Z.; Andalib, A. A short review on structure and role of cyclic-3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate-specific phosphodiesterase 4 as a treatment tool. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2015, 4, 175–181.

- Heikaus, C.C.; Pandit, J.; Klevit, R.E. Cyclic nucleotide binding GAF domains from phosphodiesterases: Structural and mechanistic insights. Structure 2009, 17, 1551–1557.

- Tian, Y.; Cui, W.; Huang, M.; Robinson, H.; Wan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, H. Dual specificity and novel structural folding of yeast phosphodiesterase-1 for hydrolysis of second messengers cyclic adenosine and guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 4938–4945.

- Luo, Y.; Helmann, J.D. Analysis of the role of Bacillus subtilis σ(M) in β-lactam resistance reveals an essential role for c-di-AMP in peptidoglycan homeostasis. Mol. Microbiol. 2012, 83, 623–639.

- Fahmi, T.; Port, G.C.; Cho, K.H. c-di-AMP: An Essential Molecule in the Signaling Pathways that Regulate the Viability and Virulence of Gram-Positive Bacteria. Genes 2017, 8, 197.

- Galperin, M.Y.; Natale, D.A.; Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. A specialized version of the HD hydrolase domain implicated in signal transduction. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 1, 303–305.

- Gao, J.; Tao, J.; Liang, W.; Zhao, M.; Du, X.; Cui, S.; Duan, H.; Kan, B.; Su, X.; Jiang, Z. Identification and characterization of phosphodiesterases that specifically degrade 3′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 539–550.

- Wright, T.A.; Jiang, L.; Park, J.J.; Anderson, W.A.; Chen, G.; Hallberg, Z.F.; Nan, B.; Hammond, M.C. Second messengers and divergent HD-GYP phosphodiesterases regulate 3′,3′-cGAMP signaling. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 113, 222–236.