In Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli (Template:Lang-nci-IPA, modern Nahuatl pronunciation (help·info)) is the deity of war, sun, human sacrifice, and the patron of the city of Tenochtitlan. He was also the tribal god of the Mexicas, also known as the Aztecs, of Tenochtitlan. Many in the pantheon of deities of the Aztecs were inclined to have a fondness for a particular aspect of warfare. However, Huitzilopochtli was known as the primary god of war in ancient Mexico. Since he was the patron god of the Mexica, he was credited with both the victories and defeats that the Mexica people had on the battlefield. The people had to make sacrifices to him to protect the Aztec from infinite night. He wielded Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, as a weapon, thus also associating Huitzilopochtli with fire. As noted by the Spaniards during their discovery and conquest of the Aztec Empire (wherein they recorded the deity's name as Huichilobos), human sacrifice was common in worship ceremonies, which took place frequently and in numerous temples throughout the region, and when performed they typically sacrificed multiple victims per day at a given temple.

- huitzilopochtli

- huichilobos

- xiuhcoatl

1. Etymology

There continues to be disagreement about the full significance of Huītzilōpōchtli's name. [1] Generally it is agreed that there are two elements, huītzilin "hummingbird" and ōpōchtli "left hand side." The name is often translated as "Left-Handed Hummingbird" or "Hummingbird of the South" on the basis that Aztec cosmology associated the south with the left hand side of the body.[2] [3]

However, Frances Karttunen points out that in Classical Nahuatl compounds are usually head final, implying that a more accurate translation may be "the left (or south) side of the hummingbird".

The hummingbird was spiritually important in Aztec culture. Diego Durán describes what appears to be the hummingbird hibernating in a tree, somewhat like the common poorwill does. He writes, "It appears to be dead, but at the advent of spring, ... the little bird is reborn."[4]

2. Origin Stories

There are a handful of origin mythologies describing the deity's beginnings. One story tells of the cosmic creation and Huitzilopochtli's role in it. According to this legend, he was the smallest son of four — his parents being the creator couple of the Ōmeteōtl (Tōnacātēcuhtli and Tōnacācihuātl) while his brothers were Quetzalcōātl ("Precious Serpent" or "Quetzal-Feathered Serpent"), Xīpe Tōtec ("Our Lord Flayed"), and Tezcatlipōca ("Smoking Mirror"). His mother and father instructed him and Quetzalcoatl to bring order to the world. Together, Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl created fire, the first male and female humans, the Earth, and the Sun.[5]

Another origin story tells of a fierce goddess, Coatlicue, being impregnated as she was sweeping by a ball of feathers on Mount Coatepec ("Serpent Hill"; near Tula, Hidalgo).[6][7][8] Her other children, who were already fully grown, were the four hundred male Centzonuitznaua and the female deity Coyolxauhqui. These children, angered by the manner by which their mother became impregnated, conspired to kill her.[9] Huitzilopochtli burst forth from his mother's womb in full armor and fully grown, or in other versions of the story, burst forth from the womb and immediately put on his gear.[10] He attacked his older brothers and sister, defending his mother by beheading his sister and casting her body from the mountain top. He also chased after his brothers, who fled from him and became scattered all over the sky.[11]

Huitzilopochtli is seen as the sun in mythology, while his many male siblings are perceived as the stars and his sister as the moon. In the Aztec worldview, this is the reason why the Sun is constantly chasing the Moon and stars. It is also why it was so important to provide tribute for Huitzilopochtli as sustenance for the Sun.[12] If Huitzilopochtli did not have enough strength to battle his siblings, they would destroy their mother and thus the world.

3. History

Huitzilopochtli was the patron god of the Mexica tribe. Originally he was of little importance to the Nahuas, but after the rise of the Aztecs, Tlacaelel reformed their religion and put Huitzilopochtli at the same level as Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, and Tezcatlipoca, making him a solar god. Through this, Huitzilopochtli replaced Nanahuatzin, the solar god from the Nahua legend. Huitzilopochtli was said to be in a constant struggle with the darkness and required nourishment in the form of sacrifices to ensure the sun would survive the cycle of 52 years, which was the basis of many Mesoamerican myths.

There were 18 especially holy festive days, and only one of them was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. This celebration day, known as Toxcatl,[13] falls within the fifteenth month of the Mexican calendar. During the festival, captives and slaves were brought forth and slain ceremoniously.[14]

Every 52 years, the Nahuas feared the world would end as the other four creations of their legends had. Under Tlacaelel, Aztecs believed that they could give strength to Huitzilopochtli with human blood and thereby postpone the end of the world, at least for another 52 years.

3.1. Sacrifice

Ritual Sacrifice and self bloodletting was a key offering to Huitzilopochtli, who demanded blood in order to be appeased. So individual bloodletting became a daily ritual for the Aztecs regardless of your age, gender or social status of the victim. Animals were also regularly sacrificed in both private and public. Though the most important was public human sacrifice. They would sacrifice normally prisoners of war with great pageantry and ritual by the high priest. Aztec warriors in battle would often wound an opponent rather then kill them, in order to capture them and bring them back for sacrifice. They would normally kill these victims by the use of a sacred sacrificial dagger. A common thread throughout these sacrifices was that the heart of the victim would be cut out, and the a still pulsating organ would be held up high for all to see. War was an important source of both human and material tribute. Human tribute was used for sacrificial purposes because human blood was believed to be extremely important, and thus powerful. According to Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli needed blood as sustenance in order to continue to keep his sister and many brothers at bay as he chased them through the sky.

In the book El Calendario Mexica y la Cronografia by Rafael Tena and published by the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico, the author gives the last day of the Nahuatl month Panquetzaliztli as the date of the celebration of the rebirth of the Lord Huitzilopochtli on top of Coatepec (Snake Hill); December 9 in the Julian calendar or December 19 in the Gregorian calendar with the variant of December 18 in leap years.

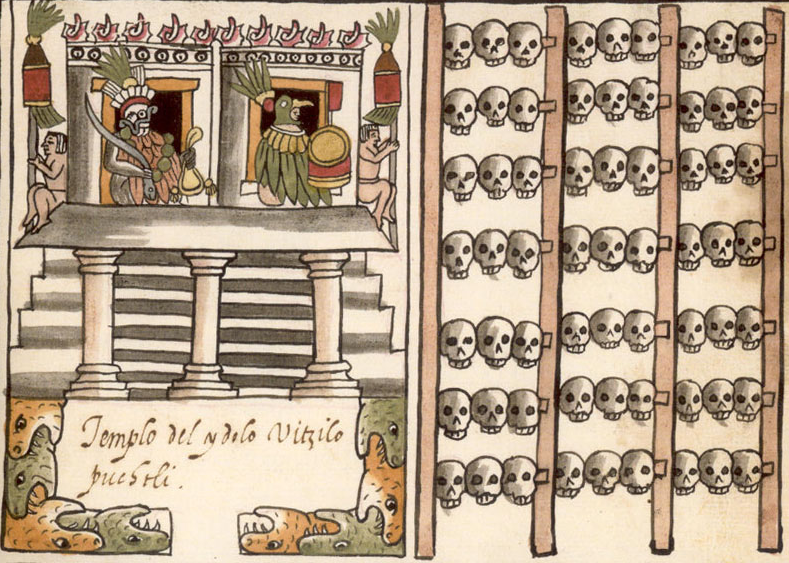

4. The Templo Mayor

The most important and powerful structure in Tenochtitlan is the Templo Mayor. Its importance as the sacred center is reflected in the fact that it was enlarged frontally eleven times during the two hundred years of its existence.[15] The Great Temple of Tenochtitlan was dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, the rain god. 16th century Dominican Friar Diego Durán wrote, "These two gods were always meant to be together, since they were considered companions of equal power."[16] The Templo Mayor actually consisted of a pyramidal platform, on top of which were twin temples. The South one was Huitzilopochtli's, and the North one was Tlaloc's. That these two deities were on opposite sides of the Great Temple is very representative of the Aztec dichotomy that the deities represent. Tlaloc, as the rain god, represented fertility and growth, while Huitzilopochtli, as the sun god, represented war and sacrifice.[17] The Templo Mayor is made up of two shrines side by side; one painted with blue stripes and the other painted red. The blue shrine was to Tlaloc and represented the rainy season and the summer solstice. The red shrine was to Huitzilopochtli, painted to symbolize blood and war. Although the shrines were next to each other, Huitzilopochtli's was toward the south side.[18]

5. The Coyolxauhqui Stone

The Coyolxauhqui stone was found directly at the base of the stairway leading up to Huitzilopochtli's temple. On both sides of the stairway's base were two large grinning serpent heads. The image is clear. The Templo Mayor is the image of Coatepec or Serpent Mountain where the divine battle took place. Just as Huitzilopochtli triumphed at the top of the mountain, while his sister was dismembered and fell to pieces below, so Huitzilopochtli's temple and icon sat triumphantly at the top of the Templo Mayor while the carving of the dismembered goddess lay far below.[19] This drama of sacrificial dismemberment was vividly repeated in some of the offerings found around the Coyolxauhqui stone in which the decapitated skulls of young women were placed. This suggestion is that there was a ritual reenactment of the myth at the dedication of the stone sometime in the latter part of the fifteenth century.[20]

6. Mythology

According to Miguel León-Portilla, in this new vision from Tlacaelel, the warriors that died in battle and women who died in childbirth would go to serve Huitzilopochtli in his palace (in the south, or left).[21] From a description in the Florentine Codex, Huitzilopochtli was so bright that the warrior souls had to use their shields to protect their eyes. They could only see the god through the arrow holes in their shields, so it was the bravest warrior who could see him best. Warriors and women who died during childbirth were transformed into hummingbirds upon death and went to join Huitzilopochtli.[22]

As the precise studies of Johanna Broda have shown, the creation myth consisted of “several layers of symbolism, ranging from a purely historical explanation to one in terms of cosmovision and possible astronomical content.”[23] At one level, Huitzilopochtli's birth and victorious battle against the four hundred children represent the character of the solar region of the Aztecs in that the daily sunrise was viewed as a celestial battle against the moon (Coyolxauhqui) and the stars (Centzon Huitznahua).[24] Another version of the myth, found in the historical chronicles of Diego Duran and Alvarado Tezozomoc, tells the story with strong historical allusion and portrays two Aztec factions in ferocious battle. The leader of one group, Huitzilopochtli, defeats the warriors of a woman leader, Coyolxauh, and tears open their breasts and eats their hearts.[25] Both versions tell of the origin of human sacrifice at the sacred place, Coatepec, during the rise of the Aztec nation and at the foundation of Tenochtitlan.[26]

7. Origins of Tenochtitlan

There are several legends and myths of Huitzilopochtli. According to the Aubin Codex, the Aztecs originally came from a place called Aztlán. They lived under the ruling of a powerful elite called the "Azteca Chicomoztoca". Huitzilopochtli ordered them to abandon Aztlán and find a new home. He also ordered them never to call themselves Aztec; instead they should be called "Mexica."[27] Huitzilopochtli guided them through the journey. For a time, Huitzilopochtli left them in the charge of his sister, Malinalxochitl, who, according to legend, founded Malinalco, but the Aztecs resented her ruling and called back Huitzilopochtli. He put his sister to sleep and ordered the Aztecs to leave the place. When she woke up and realized she was alone, she became angry and desired revenge. She gave birth to a son called Copil. When he grew up, he confronted Huitzilopochtli, who had to kill him. Huitzilopochtli then took his heart out and threw it in the middle of Lake Texcoco. Many years later, Huitzilopochtli ordered the Aztecs to search for Copil's heart and build their city over it. The sign would be an eagle perched on a cactus, eating a precious serpent, and the place would become their permanent home.[28] After much traveling, they arrived at the area which would eventually be Tenochtitlan on an island in the Lago Texcoco of the Valley of Mexico.

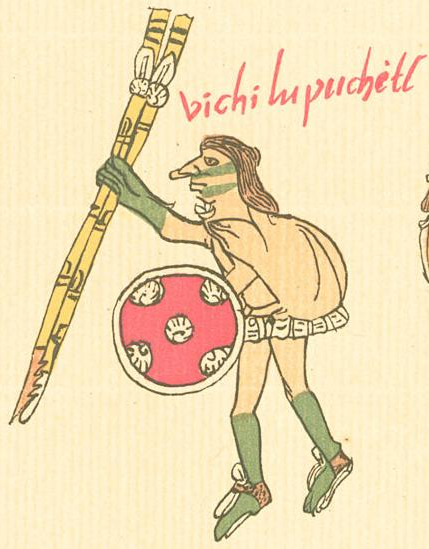

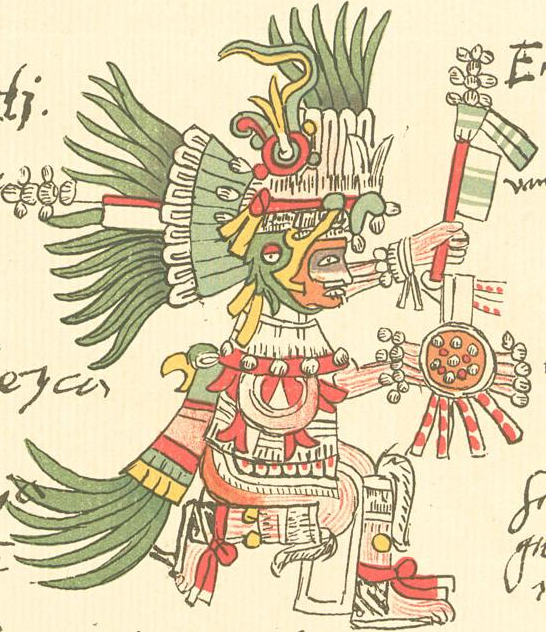

8. Iconography

In art and iconography, Huitzilopochtli could be represented either as a hummingbird or as an anthropomorphic figure with just the feathers of such on his head and left leg, a black face, and holding a scepter shaped like a snake and a mirror. According to the Florentine Codex, Huitzilopochtli's body was painted blue.[29] In the great temple his statue was decorated with cloth, feathers, gold, and jewels, and was hidden behind a curtain to give it more reverence and veneration. Another variation lists him having a face that was marked with yellow and blue stripes and he carries around the fire serpent Xiuhcoatl with him.[30] According to legend, the statue was supposed to be destroyed by the soldier Gil González de Benavides, but it was rescued by a man called Tlatolatl. The statue appeared some years later during an investigation by Bishop Zummáraga in the 1530s, only to be lost again. There is speculation that the statue still exists in a cave somewhere in the Anahuac Valley.

He always had a blue-green hummingbird helmet in any of the depictions found. In fact, his hummingbird helmet was the one item that consistently defined him as Huitzilopochtli, the sun god, in artistic renderings.[31] He is usually depicted as holding a shield adorned with balls of eagle feathers, an homage to his mother and the story of his birth.[32] He also holds the blue snake, Xiuhcoatl, in his hand in the form of an atlatl, or spear thrower.[33]

9. Calendar

Diego Durán described the festivities for Huitzilopochtli. Panquetzaliztli (November 9 to November 28) was the Aztec month dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. People decorated their homes and trees with paper flags; there were ritual races, processions, dances, songs, prayers, and finally human sacrifices. This was one of the more important Aztec festivals, and the people prepared for the whole month. They fasted or ate very little; a statue of the god was made with amaranth (huautli) seeds and honey, and at the end of the month, it was cut into small pieces so everybody could eat a little piece of the god. After the Spanish conquest, cultivation of amaranth was outlawed, while some of the festivities were subsumed into the Christmas celebration.

According to the Ramírez Codex, in Tenochtitlan approximately sixty prisoners were sacrificed at the festivities. Sacrifices were reported to be made in other Aztec cities, including Tlatelolco, Xochimilco, and Texcoco, but the number is unknown, and no currently available archeological findings confirm this.

For the reconsecration of Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan in 1487, dedicated to Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli, the Aztecs reported that they sacrificed about 20,400 prisoners over the course of four days. While accepted by some scholars, this claim also has been considered Aztec propaganda. There were 19 altars in the city of Tenochtitlan.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Hu%C4%ABtzil%C5%8Dp%C5%8Dchtli

References

- Karttunen, Frances (1992). An Analytical Dictionary of Nahuatl. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 91. ISBN 978-0-8061-2421-6. https://archive.org/details/analyticaldictio00kart.

- aunque el término ha sido traducido habitualmente como 'colibrí zurdo' o 'colibrí del sur', existe desacuerdo entorno al significado ya que el ōpōchtli 'parte izquierda' es el modificado y no el modificador por estar a la derecha, por lo que la traducción literal sería 'parte izquierda de colibrí', ver por ejemplo, F. Karttunen (1983), p. 91

- "Huitzilopochtli". Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Huitzilopochtli.

- "For six months of the year [the huitzitzilin] is dead, and for six it is alive. And, as I have said, when it feels that winter is coming, it goes to a perennial, leafy tree and with its natural instinct seeks out a crack. It stands upon a twig next to that crack, pushes its beak into it as far as possible, and stays there for six months of the year--the entire duration of the winter--nourishing itself with the essence of the tree. It appears to be dead, but at the advent of spring, when the tree acquires new life and gives forth new leaves, the little bird, with the aid of the tree's life, is reborn. It goes from there to breed, and consequently the Indians say that it dies and is reborn."Diego Durán (1971). Book of Gods and Rites. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Read, Kay Almere (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 193. ISBN 978-0-19-514909-8. https://archive.org/details/mesoamericanmyth0000read.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 216.

- Durán, Fray Diego (October 1994). The History of the Indies of New Spain. Translated by Heyden, Doris. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 584. ISBN 978-0-8061-2649-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=193tKPdM-ykC&pg=PA584.

- Jordan, David K. (January 23, 2016). "Readings in Classical Nahuatl: The Murders of Coatlicue and Coyolxauhqui". http://pages.ucsd.edu/~dkjordan/nahuatl/ReadingCoatlicue.html.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 217.

- "The Birth of Huitzilopochtli, Patron God of the Aztecs". http://www.phs.poteau.k12.ok.us/williame/APAH/readings/The%20Birth%20of%20Huitzilophochtli,%20Patron%20God%20of%20the%20Aztecs.pdf.

- Read, Kay Almere (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 193. ISBN 978-0-19-514909-8. https://archive.org/details/mesoamericanmyth0000read.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 217.

- Read, Kay Almere (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 194. ISBN 978-0-19-514909-8. https://archive.org/details/mesoamericanmyth0000read.

- Brinton, Daniel (1890). Rig Veda Americanus. Philadelphia. pp. 18. https://archive.org/details/rigvedaamerican00bringoog.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of the Empire. Boulder, Colorado: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 167. ISBN 978-0226094878.

- Diego Durán, Book of Gods and Rites

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 221.

- Cartwright, Mark. "Huitzilopochtli". https://www.worldhistory.org/Huitzilopochtli/.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of the Empire. Boulder, Colorado: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 167. ISBN 978-0226094878.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of the Empire. Boulder, Colorado: University of Chicago Press. pp. 167. ISBN 978-0226094878.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 211.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 204.

- Broda, Johanna (2001). Cosmovision, Ritual E Identidad de Los Pueblos Indigenas de Mexico. Fondo de Cultura Economica USA. ISBN 9789681661786.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of the Empire. Boulder, Colorado: University of Chicago Press. pp. 167. ISBN 978-0226094878.

- de San Anton Munon Chimalpahin, Don Domingo (1997). Codex Chimalpahin, Volume 2: Society and Politics in Mexico Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Texcoco, Culhuacan, and Other Nahua Altepetl in Central Mexico. Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806129501.

- Carrasco, David (1982). Quetzalcoatl and the Irony of the Empire. Boulder, Colorado: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 167. ISBN 978-0226094878.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson. pp. 187.

- Read, Kay Almere (2000). Mesoamerican Mythologies: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 193.

- Sahagún, Bernardino. Florentine Codex. Book III, Chapter 1: Miguel Leon-Portilla.

- "Who Are the Deities of War and Battle?". About.com Religion & Spirituality. http://atheism.about.com/od/aztecgodsgoddesses/p/Huitzilopochtli.htm.

- Read, Key Almere (2000). Mesoamerican Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs of Mexico and Central America. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 195. ISBN 978-0-19-514909-8. https://archive.org/details/mesoamericanmyth0000read.

- Sahagún, Bernardino. Florentine Codex. Book III, Chapter 1: Miguel Leon-Portilla.

- "God of the Month: Huitzilopochtli". http://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/gods/god-of-the-month-huitzilopochtli.