Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Fenbendazole (FZ) is a benzimidazole carbamate drug with broad-spectrum antiparasitic activity in humans and animals. The mechanism of action of FZ is associated with microtubular polymerization inhibition and glucose uptake blockade resulting in reduced glycogen stores and decreased ATP formation in the adult stages of susceptible parasites.

- fenbendazole

- microtubule polymerization

- self-administration

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, a considerable amount of research has been conducted on novel oncological therapies; however, cancer remains a major global cause of morbidity and mortality [1]. Developing novel anticancer drugs requires considerable funding for large-scale investigations, experimentation, testing, corroboration, and the subsequent evaluation of efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity [2]. After this arduous process, only 5% of oncology drugs enter phase I clinical trials [3]. Chemotherapy is considered to be one of the most methodical and vigorous strategies to treat malignant tumors. However, the development of multidrug resistance in patients with cancer receiving traditional chemotherapeutics causes 90% of deaths [4]. Under these circumstances, new therapeutic alternatives are in demand. However, the conventional method of developing new anticancer drugs is onerous, stringent, and costly. The estimated time to discover a single drug candidate is 11.4–13.5 years, and it costs approximately USD 1–2.5 billion to take it through all the obligatory trials required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [5].

Drug repurposing or reprofiling has gained recognition and has enabled existing pharmaceutical products to be reconsidered for promising alternative applications, as their pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and toxicity profile are already well-known in animals and humans [6]. With repurposing, new drugs could be ready for clinical trials faster, reducing development time; this is also economically appealing by expediting integration into medical practice compared with other drug development strategies [7][8]. Examples of high-potential drugs recognized within the Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) project include clarithromycin, cimetidine, diclofenac, mebendazole (MBZ), and nitroglycerine [8]. In addition, several antiparasitic drugs that have been in clinical use for decades have been investigated for repurposing in oncology [9]. The repositioning of anthelminthic pleiotropic benzimidazole carbamate (BZ) group drugs such as MBZ, albendazole (ABZ), and flubendazole has recently opened new avenues in cancer treatment owing to their easy access, low cost as generic drugs, and safety in human application [10][11]. Another potent and efficient pharmacological candidate from this group for repurposing as an anticancer drug is fenbendazole (FZ), which is widely used in veterinary medicine to treat parasitic worms including ascarids, whipworms, hookworms, and a single species of tapeworm, Taenia pisiformis, in humans and animals [12]. Although there are considerable research and successful cases regarding the anticancer activity and mechanism of action of FZ, there is ongoing social controversy concerning its application in cancer treatment [13][14].

2. Fenbendazole

Methyl N-(6-phenylsulfanyl-1H-benzimidazole-2-yl (FZ) is a safe broad-spectrum antiparasitic drug [12] with proven applications in treating different types of parasitic infections caused by helminths in livestock [15], companion animals [16][17], and laboratory animals [18]. It has a high safety margin with a low degree of toxicity in experimental animals [19] and is well-tolerated by most species, even at sixfold the prescribed dose and threefold the recommended duration. The FZ dosage for dogs is 50 mg/kg/day for 3 days, and it is also safely administered at specific doses in other livestock [20]. Orally administered FZ is poorly absorbed in the bloodstream; thus, it is necessary to retain FZ as long as possible in the rumen, where it is progressively absorbed for higher efficacy. Rarely found side effects are diarrhea and vomiting. Metabolism to its sulfoxide derivative is mainly in the liver, and excretion occurs mainly through feces with a very small amount excreted via urine.

3. Mechanism of Action

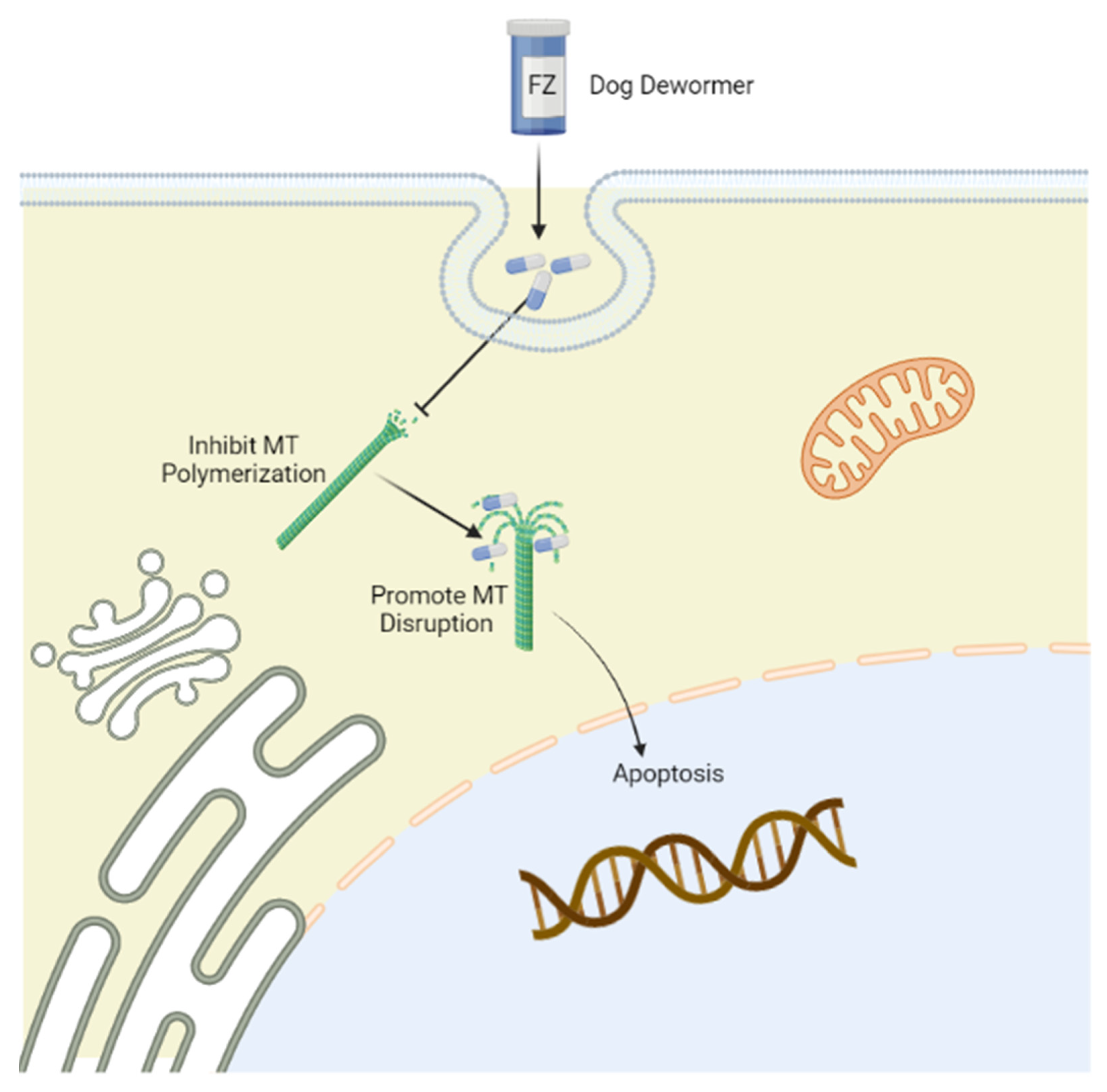

FZ primarily inhibits tubulin polymerization and promotes microtubular (MT) disruption in parasite cells (Figure 1) [21]. Tubulin, a structural protein of MTs, is the leading molecular target of benzimidazoles [22] and has prominent functions in cell proliferation, motility, division, the intercellular transport of organelles, the maintenance of the cell shape, and the secretion process of cells in all living organisms [23]. By binding with beta-tubulin, FZ blocks MT polymerization in worms and thus perturbs glucose uptake, eventually emptying glycogen reserves and adversely affecting energy management mechanisms. As a result, the whole process eventually contributes to the death of the parasites [20]. Additionally, the poor absorption of FZ from the intestine manifests as reduced levels of drugs and their active ingredients in tissues compared with those within the gut, where the targeted parasites are present [24].

Figure 1. Mechanism of action of fenbendazole (FZ) targeting tubulin. Tubulin is the leading molecular target of FZ, which selectively binds to the β-tubulin of microtubules to disrupt microtubular polymerization, promoting immobilization and the death of parasites. The figure was created using Biorender (https://biorender.com/) (accessed on 15 May 2022).

4. Anticancer Activity of FZ

MTs are one of the major components of the cytoskeleton, and their role in cell division, the maintenance of cell shape and structure, motility, and intracellular trafficking renders them one of the most important targets for anticancer therapy. Several broadly used anticancer drugs induce their antineoplastic effects by perturbing MT dynamics. A class of anticancer drugs acts by inhibiting MT polymerization (vincristine, vinblastine), while another class stabilizes MTs (paclitaxel, docetaxel), suggesting that FZ could have potential anticancer effects [25][26]. The consequence of disrupting tubulin and dynamic MT stability with these classes of anticancer drugs in dividing cells is apoptosis and metaphase arrest. FZ exhibits moderate MT depolymerizing activity in human cancer cell lines, and has a potent anticancer effect in vitro and in vivo [27].

5. Anticancer Activity of FZ in Preclinical Models

The anticancer activity of FZ has been investigated in different cell lines. FZ exhibits depolymerizing MT activity toward human cancer cell lines that manifests as a significant anticancer effect in vitro and in vivo. The mechanism of action of the FZ antitumor effect is predominantly the disruption of MT dynamics, p53 activation, and the regulation of genes associated with multiple biological pathways. FZ treatment also causes the depletion of glucose uptake in cancer cells by downregulating key glycolytic enzymes and GLUT transporters [24][27][28]. FZ selectively inhibits the growth of H4IIE cells by upregulating p21, and downregulating cyclins B and D at G1/S and G2/M phases, resulting in apoptosis exclusively in actively growing cells with low confluency, but not in quiescent cells. MAPKs, glucose generation, and ROS are unlikely targets of FZ in H4IIE rat hepatocellular carcinoma cells [29]. Treating human cancer cell lines with FZ induces apoptosis, whereas normal cells remain unaffected. Many apoptosis regulatory proteins such as cyclins, p53, and IκBα that are normally degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway accumulate in FZ-treated cells. Moreover, FZ produced distinct endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress-associated genes, such as ATF3, GADD153, GRP78, IRE1α, and NOXA, in experimental cells. Thus, FZ treatment in human cancer cells induced decreased mitochondrial membrane potential, ROS production, ER stress, and cytochrome c release, eventually leading to cancer cell death [30]. FZ exhibits considerable affinity for mammalian tubulin in MT and is toxic in human cancer cells (H460, A549) at micromolar concentrations. Additionally, FZ exposure causes the mitochondrial translocation of p53, and effectively inhibits the expression of GLUT transporters, glucose uptake, and levels of hexokinase, which is a key glycolytic enzyme potentially linked to p53 activation and the alteration of MT dynamics. Orally administered FZ successfully blocked the growth of human xenografts in a nu/nu mice model [27]. Moreover, Qiwen et al. reported that FZ treatment is toxic to EMT6 mouse mammary tumor cells in vitro, with toxicity increasing after 24 h incubation with high FZ doses. However, FZ did not alter the dose–response curves for radiation on EMT6 cells under either aerobic or hypoxic conditions [24]. In contrast, Ping et al. reported that FZ or vitamins alone had no growth inhibitory effect on P493-6 human lymphoma cell lines in SCID mice. In combination with vitamin supplements, FZ significantly inhibited tumor growth through its antimicrotubular activity [31]. The effect of a therapeutic diet containing 150 ppm FZ for 6 weeks on the growth of EMT6 mouse mammary tumors in BALB/c mice injected intradermally was examined. The results revealed that the FZ diet did not alter tumor growth, metastasis, or invasion. Therefore, the authors suggested being cautious in applying FZ diets to mouse colonies used in cancer research. [32]. HL-60 cells, a human leukemia cell line, were treated with FZ to investigate the anticancer potential in the absence or presence of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), an inhibitor of ROS production. NAC could significantly recover the decreased metabolic activity of HL-60 cells induced by 0.5–1 μM FZ treatments. The results proved that FZ manifests anticancer activity in HL-60 cells via ROS production [33]. Ji-Yun also reported the antitumor effect of FZ and paclitaxel via ROS on HL-60 cells at a certain concentration [34]. Moreover, FZ and its synthetic analog induced oxidative stress by accumulating ROS. In addition, FZ activated the p38-MAPK signaling pathway to inhibit the proliferation and increase the apoptosis of HeLa cells. FZ also impaired glucose metabolism, and prevented HeLa cell migration and invasion [35]. Koh et al. found that FZ, MBZ, and oxibendazole possess remarkable anticancer activities at the cellular level via tubulin depolymerization, but their poor pharmacokinetic parameters limit their use as systemic anticancer drugs. However, the same authors assured patients on the application of oxibendazole or FZ as a cancer treatment option [13]. Thus, FZ was investigated using a novel transcriptional drug repositioning approach based on both bioinformatic and cheminformatic components for the identification of new active compounds and modes of action. FZ induced the differentiation of leukemia cells, HL60, to granulocytes, at a low concentration of 0.1 μM within 3 days, causing apoptosis in cancer cells [36].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cimb44100338

References

- Tahlan, S.; Kumar, S.; Kakkar, S.; Narasimhan, B. Benzimidazole scaffolds as promising antiproliferative agents: A review. BMC Chem. 2019, 13, 66.

- Armando, R.G.; Mengual Gomez, D.L.; Gomez, D.E. New drugs are not enoughdrug repositioning in oncology: An update. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 56, 651–684.

- Kato, S.; Moulder, S.L.; Ueno, N.T.; Wheler, J.J.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Kurzrock, R.; Janku, F. Challenges and perspective of drug repurposing strategies in early phase clinical trials. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 576–580.

- Bukowski, K.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3233.

- Scannell, J.W.; Blanckley, A.; Boldon, H.; Warrington, B. Diagnosing the decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2012, 11, 191–200.

- Bertolini, F.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Bouche, G. Drug repurposing in oncology—Patient and health systems opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 12, 732–742.

- Castro, L.S.; Kviecinski, M.R.; Ourique, F.; Parisotto, E.B.; Grinevicius, V.M.; Correia, J.F.; Wilhelm Filho, D.; Pedrosa, R.C. Albendazole as a promising molecule for tumor control. Redox Biol. 2016, 10, 90–99.

- Pantziarka, P.; Bouche, G.; Meheus, L.; Sukhatme, V.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Vikas, P. The Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO) Project. Ecancermedicalscience 2014, 8, 442.

- Hu, Y.; Ellis, B.L.; Yiu, Y.Y.; Miller, M.M.; Urban, J.F.; Shi, L.Z.; Aroian, R.V. An extensive comparison of the effect of anthelmintic classes on diverse nematodes. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70702.

- Nath, J.; Paul, R.; Ghosh, S.K.; Paul, J.; Singha, B.; Debnath, N. Drug repurposing and relabeling for cancer therapy: Emerging benzimidazole antihelminthics with potent anticancer effects. Life Sci. 2020, 258, 118189.

- Sultana, T.; Jan, U.; Lee, J.I. Double Repositioning: Veterinary Antiparasitic to Human Anticancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4315.

- Baeder, C.; Bahr, H.; Christ, O.; Duwel, D.; Kellner, H.M.; Kirsch, R.; Loewe, H.; Schultes, E.; Schutz, E.; Westen, H. Fenbendazole: A new, highly effective anthelmintic. Experientia 1974, 30, 753–754.

- Jiyoon, J.; Kwangho, L.; Byumseok, K. Investigation of benzimidazole anthelmintics as oral anticancer agents. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2022, 43, 750–756.

- Heo, D.S. Anthelmintics as Potential Anti-Cancer Drugs? J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e75.

- Crotch-Harvey, L.; Thomas, L.A.; Worgan, H.J.; Douglas, J.L.; Gilby, D.E.; McEwan, N.R. The effect of administration of fenbendazole on the microbial hindgut population of the horse. J. Equine Sci. 2018, 29, 47–51.

- Hayes, R.H.; Oehme, F.W.; Leipold, H. Toxicity investigation of fenbendazole, an anthelmintic of swine. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1983, 44, 1108–1111.

- Schwartz, R.D.; Donoghue, A.R.; Baggs, R.B.; Clark, T.; Partington, C. Evaluation of the safety of fenbendazole in cats. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2000, 61, 330–332.

- Villar, D.; Cray, C.; Zaias, J.; Altman, N.H. Biologic effects of fenbendazole in rats and mice: A review. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2007, 46, 8–15.

- Muser, R.K.; Paul, J.W. Safety of fenbendazole use in cattle. Mod. Vet. Pract. 1984, 65, 371–374.

- Junquera, P. FENBENDAZOLE, Anthelmintic for Veterinary Use in CATTLE, SHEEP, GOATS, PIG, POULTRY, HORSES, DOGS and CATS against Roundworms and Tapeworms. 2015. Available online: https://parasitipedia.net/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Gull, K.; Dawson, P.J.; Davis, C.; Byard, E.H. Microtubules as target organelles for benzimidazole anthelmintic chemotherapy. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1987, 15, 59–60.

- Lacey, E.; Watson, T.R. Structure-activity relationships of benzimidazole carbamates as inhibitors of mammalian tubulin, in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1985, 34, 1073–1077.

- Jordan, M.A.; Wilson, L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2004, 4, 253–265.

- Duan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Rockwell, S. Fenbendazole as a potential anticancer drug. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 355–362.

- Spagnuolo, P.A.; Hu, J.; Hurren, R.; Wang, X.; Gronda, M.; Sukhai, M.A.; Di Meo, A.; Boss, J.; Ashali, I.; Beheshti Zavareh, R.; et al. The antihelmintic flubendazole inhibits microtubule function through a mechanism distinct from Vinca alkaloids and displays preclinical activity in leukemia and myeloma. Blood 2010, 115, 4824–4833.

- Jordan, M.A. Mechanism of action of antitumor drugs that interact with microtubules and tubulin. Curr. Med. Chem. Anticancer Agents 2002, 2, 1–17.

- Dogra, N.; Kumar, A.; Mukhopadhyay, T. Fenbendazole acts as a moderate microtubule destabilizing agent and causes cancer cell death by modulating multiple cellular pathways. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11926.

- Sharma, Y. Veterinary drug may be repurposed for human cancers: Study. The Hindu Business Line, 27 August 2018.

- Park, D. Fenbendazole Suppresses Growth and Induces Apoptosis of Actively Growing H4IIE Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via p21-Mediated Cell-Cycle Arrest. Biol. Pharm Bull. 2022, 45, 184–193.

- Dogra, N.; Mukhopadhyay, T. Impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by methyl N-(6-phenylsulfanyl-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)carbamate leads to a potent cytotoxic effect in tumor cells: A novel antiproliferative agent with a potential therapeutic implication. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 30625–30640.

- Gao, P.; Dang, C.V.; Watson, J. Unexpected antitumorigenic effect of fenbendazole when combined with supplementary vitamins. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2008, 47, 37–40.

- Duan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Booth, C.J.; Rockwell, S. Use of fenbendazole-containing therapeutic diets for mice in experimental cancer therapy studies. J. Am. Assoc. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2012, 51, 224–230.

- Yong, H.; Joo, H.-G. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the anti-cancer activity of fenbendazole, a benzimidazole anthelmintic. Korean J. Vet. Res. 2020, 60, 79–83.

- Sung, J.Y.; Joo, H.-G. Anti-cancer effects of Fenbendazole and Paclitaxel combination on HL-60 cells. Prev. Vet. Med. 2021, 45, 13–17.

- Peng, Y.; Pan, J.; Ou, F.; Wang, W.; Hu, H.; Chen, L.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, K.; Yu, L. Fenbendazole and its synthetic analog interfere with HeLa cells’ proliferation and energy metabolism via inducing oxidative stress and modulating MEK3/6-p38-MAPK pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact 2022, 361, 109983.

- KalantarMotamedi, Y.; Ejeian, F.; Sabouhi, F.; Bahmani, L.; Nejati, A.S.; Bhagwat, A.M.; Ahadi, A.M.; Tafreshi, A.P.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.H.; Bender, A. Transcriptional drug repositioning and cheminformatics approach for differentiation therapy of leukaemia cells. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12537.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!