Bush encroachment (also shrub encroachment, woody encroachment, bush thickening, woody plant proliferation) is a natural phenomenon characterised by the increase in density of woody plants, bushes and shrubs, at the expense of the herbaceous layer, grasses and forbs. It predominantly occurs in grasslands, savannas and woodlands and can cause biome shifts from open grasslands and savannas to closed woodlands. The term bush encroachment refers to the expansion of native plants and not the spread of alien invasive species. It is thus defined by plant density, not species. Bush encroachment is often considered an ecological regime shift and can be a symptom of land degradation. Its causes include land use intensification, such as high grazing pressure and the suppression of wildfires. Climate change is found to be an accelerating factor for woody encroachment. The impact of bush encroachment is highly context specific. It is often found to have severe negative consequences on key ecosystem services, especially biodiversity, animal habitat, land productivity and groundwater recharge. Across rangelands, woody encroachment has led to significant declines of productivity, threatening the livelihoods of affected land users. The phenomenon is observed across different ecosystems and with different characteristics and intensities globally. Various countries actively counter woody encroachment, through adapted grassland management practices and targeted bush thinning. In some cases, areas affected by woody encroachment are classified as carbon sinks and form part of national greenhouse gas inventories. However, carbon sequestration effects of woody encroachment are highly context specific and still insufficiently researched.

- grassland management

- woody encroachment

- bush encroachment

1. Causes

Woody encroachment is assumed to have its origins at the beginning of Holocene and the start of warming, with tropical species expanding their ranges away from the equator into more temperate regions. But it has occurred at unparalleled rates since the mid 19th century.[1][2] Among earliest published notions of bush encroachment are publications of R. Staples in 1945,[3] O. West in 1947[4] and Heinrich Walter in 1954.[5]

Various factors have been found to contribute to the process of bush encroachment. A general distinction can be made between bush encroachment due to land intensification and bush encroachment after land abandonment. Literature further suggests that the causes of woody encroachment differ significantly between wet and dry savanna.[6] With regard to its causes, bush encroachment is distinctly different from alien plant invasion, which is caused by the spread of deliberately or accidentally introduced species.[7]

1.1. Land Abandonment

Where land is abandoned, the rapid spread of native bush plants is often observed. This is for example the case in former forest areas in the Alps that have been converted to agricultural land and later abandoned. In Southern Europe encroachment is thus linked to rural exodus.[8]

1.2. Land Intensification

Driver of woody encroachment can change over time. While overgrazing has in the past frequently been found to be a main driver of woody encroachment, it is observed that woody encroachment continues in the respective areas even after grazing reduced or even ceases.[9]

- Overgrazing: In the context of land intensification, a frequently cited cause of bush encroachment is overgrazing, commonly a result of overstocking and fencing of farms, as well as the lack of animal rotation and land resting periods. Studies find that overgrazing plays an especially strong role under mesic climatic conditions, where shrub encroachment is mainly limited by the than reduced competition from the herbaceous layer.[10] Seed dispersal through animals is found to be a contributing factor to woody encroachment.[11]

- Fire: A connected cause for bush encroachment is the reduction in the frequency of wildfires that would occur naturally, but are suppressed in frequency and intensity by land owners due to the associated risks.[12][13] When the lack of fire reduces tree mortality and consequently the grass fuel load for fires decreases, a Negative feedback loop occurs.[14] It has been estimated that from a threshold of 40% canopy cover, surface grass fires are rare.[15] At intermediate rainfall, fire can be the main determinant between the development of savannas and forests.[16][17] In experiments in the United States, it was determined that annual fires lead to the maintenance of grasslands, 4-year burn intervals lead to the establishment of shrubby habitats and 20-year burn intervals lead to severe bush encroachment.[18] Moreover, the reduction of browsing by herbivores, e.g. when natural habitats are transformed into agricultural land, fosters woody plant encroachment, as bushes grow undisturbed and with increasing size also become less susceptible to fire. Already one decade of land management change, such as the exclusion of fires and overgrazing, can lead to severe bush encroachment.[19]

- Competition for water: Another positive feedback loop occurs when encroaching woody species reduce the plant available water, providing a disadvantage for grasses, promoting further woody encroachment.[20] According to the two-layer theory, grasses use topsoil moisture, while woody plants predominantly use subsoil moisture. If grasses are reduced by overgrazing, this reduces their water intake and allows more water to penetrate into the subsoil for the use by woody plants.[5][21]

- Population pressure: population pressure can be the cause for bush encroachment, when large trees are cut as building material or fuel. This stimulates coppice growth and results in shrubbiness of the vegetation.

1.3. Global Drivers

While changes in land management are often seen as the main driver of woody encroachment, some studies suggest that global drivers increase woody vegetation regardless of land management practices.[22]

- Rainfall patterns: a frequently cited theory is the state-and-transition model. This model outlines how rainfall and its variability is the key driver of vegetation growth and its composition, bringing about bush encroachment under certain rainfall patterns.

- Climate change: climate change has been found to be a cause or accelerating factor for bush encroachment.This is because increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations fosters the growth of woody plants. Woody plants with C3 photosynthetic pathway thrive under high CO2 concentrations, as opposed to grasses with C4 photosynthetic pathway.[23][24][25][26] Also linked to climate change, changes in precipitation can foster woody encroachment. Increased precipitation can foster the establishment, growth and density of woody plants. Also decreased precipitation can promote bush encroachment, as it fosters the shift from mesophytic grasses to xerophytic shrubs.[27] Woody encroachment correlates to warming in the tundra, while it is linked to increased rainfall in the savanna.[28] Species such as Vachelllia sieberiana thrive under warming irrespective of the competition with grasses.[29] A representative sampling of South African grasslands, bush encroachment was found to be the same under different land uses and different rainfall amounts, suggesting that climate change may be the primary driver of the encroachment.[30][31] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in its report "Global warming of 1.5°C" states that high-latitude tundra and boreal forests are at particular risk of climate change-induced degradation, with a high confidence of shrubs already encroaching and this further proceedeing with further warming.[32]

1.4. Species

A wide range of different woody species have been identified as encroacher species globally. As opposed to invasive species, encroacher species are indigenous to the respective ecosystem and their classification as encroachers depends on how strongly they grow into landscapes that they previously did not dominate. Comparisons of encroaching and non-encroaching vachellia species found that encroaching species have a higher acquisition and competition for resources. Their canopy architecture is different and only encroaching tree species reduce the productivity of perennial vegetation.[33]

2. Impact on Ecosystem Services

Woody encroachment constitutes a shift in plant composition with far-reaching impact on the affected ecosystems. While it is commonly identified as a form of land degradation, with severe negative consequences for various ecosystem services, such as biodiversity, groundwater recharge, carbon storage capacity and herbivore carrying capacity, this link is not universal. Impacts are dependent on species, scale and environmental context factors and shrub encroachment can have significant positive impacts on ecosystem services as well.[34] There is a need for ecosystem-specific assessments and responses to woody encroachment.[35] Generally, the following context factors determine the ecological impact of woody encroachment:[36]

- Prevailing land use: while positive ecological effects can occur in unmanaged landscapes or certain land-uses, negative ecological effects are observed especially in landscapes under livestock grazing.[35][37]

- Density of woody plants: Plant diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality typically peaks at intermediate levels of woody cover and high woody covers generally have negative impacts.[35][38][39]

- Environmental conditions: arid environments show more negative responses to woody encroachment.[38][40]

Woody encroachment is often seen as a form of land degradation and an expression of desertification. Due to its ambiguous role of contributing to greening and desertification, it has been termed "green desertification".[41] However, the link to desertification is not universal. During woody encroachment the herbaceous cover in the intercanopy zones typically remains intact, while during desertification these zones degrade and turn into bare soil devoid of organic matter.[42] For example, in the Mediterranean region shrub establishment can contribute to the reversal of ongoing desertification.[43]

2.1. Biodiversity

Bush expands at the direct expense of other plant species, potentially reducing plant diversity and animal habitats.[44] These effects are context specific, a meta analysis of 43 publications of the time period 1978 to 2016 found that bush encroachment has distinct negative effects on species richness and total abundance in Africa, especially on mammals and herpetofauna, but positive effects in North America.[45] However, in context specific analyses also in Northern America negative effects are observed. For example, piñon-juniper encroachment threatens up to 350 sagebrush-associated plant and animal species in the USA.[46] A study of 30 years of woody encroachment in Brazil found a significant decline of species richness by 27%.[47] Shrub encroachment may result in increase vertebrate species abundance and richness. However, these encroached habitats and their species assemblages may become more sensitive to droughts.[48][49]

Evidence of biodiversity losses include the following:

- Grasses: Studies in South Africa have found that grass richness reduces by more than 50% under intense bush encroachment.[50] In North America, a meta-analysis of 29 studies from 13 different grassland communities found that species richness declined by an average of 45% under bush encroachment.[51] Among the severely affected flora is the small white lady's slipper.[52] Generally, large bushes are found to coexist with the herbaceous layer, while smaller shrubs compete with it.[53]

- Mammals: bush encroachment has a significant impact on herbivore assemblage structure[54] and can lead to the displacement of herbivores and other mammal types that prefer open areas. Among the species found to lose habitat in areas affected by bush encroachment are cats such as cheetah,[55] white-footed fox[56], as well as antelopes such as the Common tsessebe, Hirola and plains zebra.[57] In some rangelands, woody plant encroachment is associated with a decline in wildlife grazing capacity of up to 80%.[58]

- Birds: the impact of woody encroachment on bird species must be differentiated between shrub-associated species and grassland specialists. Studies find that shrub-associated species benefit from woody encroachment up to a certain threshold of woody cover (e.g. 22 percent in a study conducted in North America), while grassland specialist populations decline.[59][60] Experiments in Namibia have shown that foraging birds, such as the endangered Cape vulture, avoid encroachment levels above 2,600 woody plants per hectare.[61] In North American grasslands, bird population decline as a result of woody encroachment has been identified as a critical conservation concern.[62][63] Amongst the birds negatively affected by bush encroachment are the Secretarybird,[64] Grey go-away-bird, Marico sunbird, lesser prairie chicken,[65][66] Greater Sage-Grouse,[46] Archer's lark,[67][68] Northern bobwhite[69] and the Kori bustard.[70]

- Insects: bush encroachment is linked to species loss or reduction in species richness of insects with preference for open habitats, such as butterfly[71] and ant.[47]

2.2. Groundwater Recharge and Soil Moisture

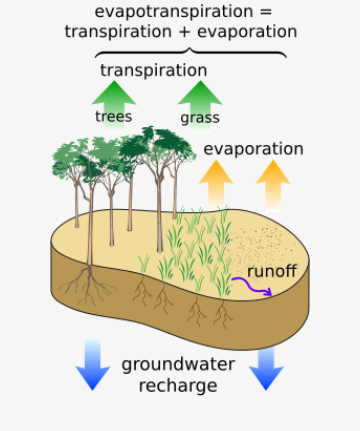

Woody plant encroachment is frequently linked to reduced groundwater recharge, based on evidence that bushes consume significantly more rainwater than grasses and encroachment alters water streamflow.[72] The downward movement of water is hindered by increased root density and depth.[73][74][75][76] The impact on groundwater recharge differs between sandstone bedrocks and karst regions as well as between deep and shallow soils.[73] Although this is strongly context dependent, bush control can be an effective method for the improvement of groundwater recharge.[77] Applied research, assessing the water availability after brush removal, was conducted in Texas USA, resulting in an increase in water availability in all cases.[78] Studies in the United States further find that dense encroachment with Juniperus virginiana is capable of transpiring nearly all rainfall, thus altering groundwater recharge significantly.[79] An exception is shrub encroachment on slopes, where groundwater recharge can increase under encroachment.[20][80]

While there is general consensus that bush encroachment has an ecohydrological impact, concrete experience with changes in groundwater recharge is however largely based on anecdotal evidence or regionally and temporally limited research projects.[81] Moreover, there is limited understanding how hydrological cycles through woody encroachment affects carbon influx and efflux, with both carbon gains and losses possible.[72]

Besides groundwater recharge, woody encroachment increases tree transpiration and evaporation of soil moisture, due to increased canopy cover.[82]

2.3. Carbon Sequestration

Against the background of global efforts to mitigate climate change, the carbon sequestration and storage capacity of natural ecosystems receives increasing attention. Grasslands constitute 40% of Earth's natural vegetation[83] and hold a considerable amount of the global Soil Organic Carbon. Shifts in plant species composition and ecosystem structure, especially through woody encroachment, leads to significant uncertainty in predicting carbon cycling in grasslands.[84][85] The impact of bush control on the carbon sequestration and storage capacity of the respective ecosystems is an important management consideration.

Research on the changes to carbon sequestration under bush encroachment and bush control is still insufficient.[86] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that bush encroachment generally leads to increased aboveground woody carbon, while belowground carbon changes depend on annual rainfall and soil type. The panel further elaborates that a global assessment of the net change in carbon stocks due to woody plant encroachment has not been conducted yet.[48] Factors relevant for comparisons of carbon sequestration potentials between encroached and non-encroached grasslands, include the following: above-ground net primary production (ANPP), below-ground net primary production (BNPP), photosynthesis rates, plant respiration rates, plant litter decomposition rates, soil microbacterial activity.

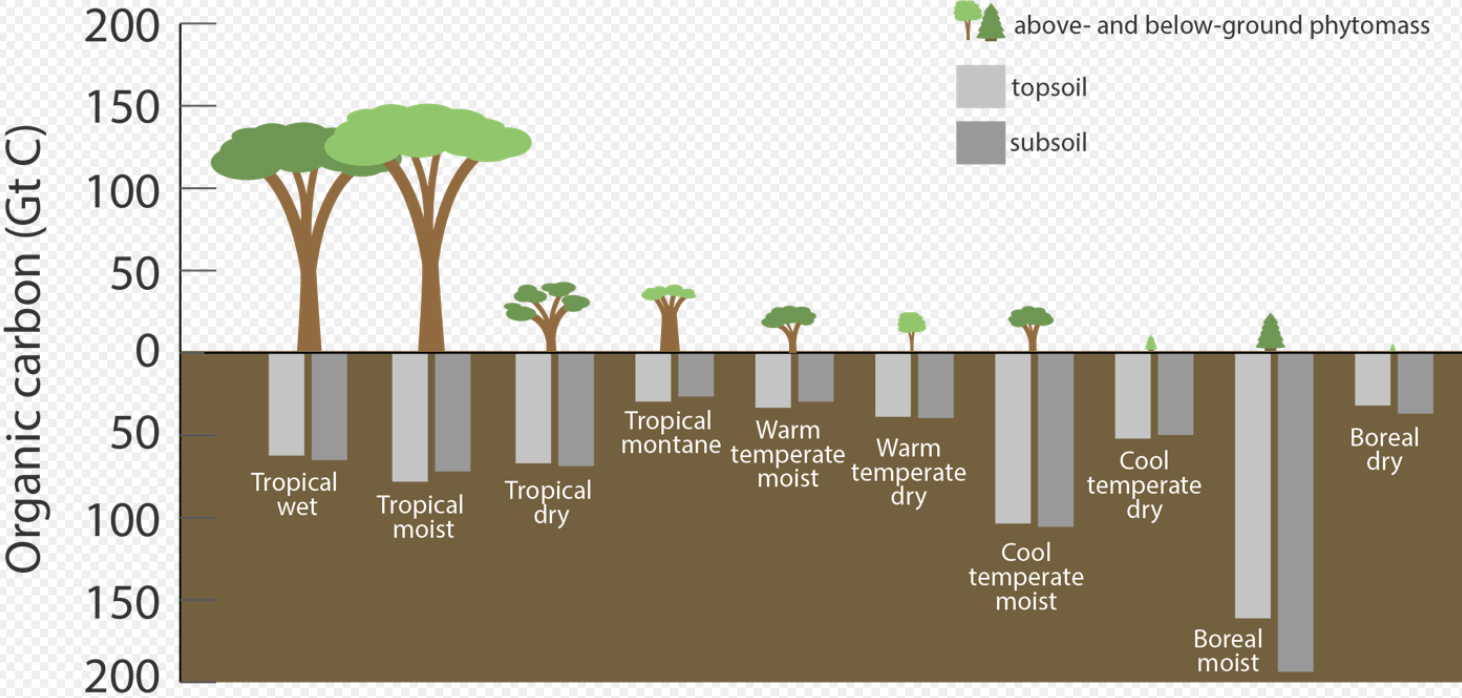

- Above-ground carbon: bush encroachment implies an increase in woody plants, in most cases at the expense of grasses. Considering that woody plants have a longer lifespan and generally also more mass, bush encroachment can imply an increase in above-ground carbon storage through biosequestration. Studies however find that this is depending on climatic conditions, with aboveground carbon pools decreasing under woody encroachment where mean annual precipitation is less than 330mm and increasing where precipitation is higher.[40][87] A contributing factor is that woody encroachment decreases above-ground plant primary production in mesic ecosystems.[40]

- Below-ground carbon: globally, the soil organic carbon pool is twice as large as the plant carbon pool, making its quantification essential. Soil organic carbon makes out two-thirds of soil carbon.[88] Comparisons of grasslands, shrublands and forests show that forest and shrubland hold more above-ground carbon, while grasslands boast more soil carbon.[89] Generally, herbaceous plants allocate more biomass below-ground than woody plants.[90][91]

- The impact of woody encroachment on soil organic carbon is found to be dependent on rainfall, with soil organic carbon increasing in dry ecosystems and decreasing in mesic ecosystems under encroachment.[92] In wet environments, grasslands have more soil carbon than shrublands and woodlands. Under shrub encroachment, the losses in soil carbon can be sufficient to offset the gains of above-ground carbon gains.[93][94][95][96][97] Degradation of grasslands has in some areas led to the loss of up to 40% of the ecosystem's soil organic carbon.[88] An important factor is that under bush encroachment the increased photosynthetic potential is largely offset by increased plant respiration and respective carbon losses.[98]

- Soil organic carbon changes need to be viewed at landscape level, as there are differences between under canopy and inter canopy processes. When a landscape becomes increasingly encroached and the remaining open grassland patches are overgrazed as a result, soil organic carbon may decrease.[34][99] In South Africa, bush encroachment was found to slow decomposition rates of litter, which took twice the time to decay under bush encroachment compared to open savannas. This suggests a significant impact of woody encroachment on the soil organic carbon balance.[100] In pastoral lands of Ethiopia, bush encroachment was found to have little to now positive effect on soil organic carbon and woody encroachment restriction was the most effective way to maintain soil organic carbon.[101] In the United States, substantial soil organic carbon sequestration was observed in deeper portions of the soil, following woody encroachment.[102]

- A meta-analysis of 142 studies found that shrub encroachment alters soil organic carbon (0–50 cm), with changes ranging between -50 and 300 percent. Soil organic carbon increased under the following conditions: semi arid and humid regions, encroachment by leguminous shrubs as opposed to non-legumes, sandy soils as opposed to clay soils. The study further concludes that shrub encroachment has a mainly positive effect on top-soil organic carbon content, with significant variations among climate, soil and shrub types.[103]

- Total ecosystem carbon: When loosely equating bush encroachment with afforestation, considering above-ground biomass alone, encroachment could be seen as a carbon sink. However, considering the losses in the herbaceous layer as well as changes in soil organic carbon, the quantification of terrestrial carbon pools and fluxes becomes more complex and context specific. Changes to carbon sequestration and storage need to be determined for each respective ecosystem and holistically, i.e. considering both above-ground and below-ground carbon storage. Generally, elevated CO2 leads to increased woody growth, which implies that the woody plants increase their uptake of nutrients from the soil, reducing the soil's capacity to store carbon. In contrast, grasses increase little biomass above-ground, but contribute significantly to below-ground carbon sequestration.[104] It is found that above-ground carbon gains might be completely offset by below-ground carbon losses during encroachment.[105] Significant carbon losses occur through increased fluvial erosion and importantly this includes previously stabilised organic carbon from legacy grasslands.[106] Some studies find that carbon sequestration can increase for a number of years under woody encroachment, while the magnitude of this increase is highly dependent on annual rainfall. It is found that woody encroachment has little impact on sequestration potential in dry areas with less than 400mm in precipitation.[93][107][108][109] Encroached ecosystems are more likely than open grasslands to lose carbon during droughts.[110] It is generally observed that carbon increases overall in wetter ecosystems under encroachment and can reduce in arid ecosystems under encroachment.[107] This implies that the positive carbon effect of woody plant encroachment may decrease with progressing climate change, particularly in ecosystems that are forecasted to experience decreased precipitation and increased temperature.[91] Among the ecosystems expected to lose carbon storage under woody encroachment is the tundra.[111] Moreover, the interplay with other climate relevant processes needs to be taken into consideration. Most significantly, woody encroachment leads to a decrease or even halt of surface fires and associated GHG emissions.[48]

2.4. Land Productivity

Bush encroachment directly impacts land productivity, as widely documented in the context of animal carrying capacity. In the Southern African country Namibia it is assumed that agricultural carrying capacity of rangelands has declined by two-thirds due to bush encroachment. In East Africa there is evidence that an increase of bush cover of 10 percent reduced grazing by 7 percent, with land becoming unusable as rangeland when the bush cover reaches 90 per cent.[112][113] In Northern America, each 1 percent of increase in woody cover implies a reduction of 0.6 to 1.6 cattle per 100 hectares.[114]

Also touristic potential of land is found to decline in areas with heavy bush encroachment, with visitors shifting to less encroached areas and better visibility of wildlife.[115]

2.5. Rural Livelihoods

While the ecological effects of woody encroachment are multifold and vary depending on encroachment density and context factors, woody encroachment is often considered to have a negative impact on rural livelihoods. In Africa 21% of the population depend on rangeland resources. Woody encroachment typically leads to an increase in less palatable woody species at the expense of palatable grasses. This reduces the resources available to pastoral communities and rangeland based agriculture at large.[116] Woody encroachment has negative consequences on livelihoods especially arid areas,[36] which support a third of the world population's livelihoods.[117][118]

2.6. Others

In the United States, woody encroachment has been linked to the spread of tick-borne pathogens and respective disease risk for humans and animals.[119] In the Arctic tundra, shrub encroachment can reduce cloudiness and contribute to a raise in temperature.[120] In Northern America, significant increases in temperature and rainfall were linked to woody encroachment, amounting to values up to 214mm and 0.68 °C respectively. This is caused by a decrease in surface albedo.[121]

Targeted bush control in combination with the protection of larger trees is found to improve scavenging that regulates disease processes, alters species distributions, and influences nutrient cycling.[122]

3. Quantification and Monitoring

There is no static definition of what is considered woody encroachment, especially when encroachment of indigenous plants occurs. While it is simple to determine vegetation trends (e.g. an increase in woody plants over time), it is more complex to determine thresholds beyond which an area is to be considered as encroached. Various definitions as well as quantification and mapping methods have been developed.

In Southern Africa, the BECVOL method (Biomass Estimates from Canopy Volume) finds frequent application. It determines Evapotranspiration Tree Equivalents (ETTE) per selected area. This data is used for comparison against climatic factors, importantly annual rainfall, to determine whether the respective areas have a higher number of woody plants than considered sustainable.[44]

Remote sensing imagery is frequently used to determine land the extend of woody encroachment. Shortcomings of this methodology include difficulties to distinguish species and the inability to detect small shrubs.[123] Moreover, UAV-based multispectral data and Lidar data are frequently used to quantify woody encroachment.[124] The probability of bush encroachment for the African continent has been mapped using GIS data and the variables precipitation, soil moisture and cattle density.[125]

Rephotography is found to be an effective tool for the monitoring of vegetation change, including woody encroachment[126] and forms the basis of various encroachment assessments.[31]

In most affected ecosystems, knowledge of historical land cover is limited to the availability of photographic evidence or written records. Methods to overcome this knowledge gap include the assessment of pollen records. In a recent application, vegetation cover of the past 130 years in a bush encroached area in Namibia was established.[127]

4. Bush Control

Bush control refers to the active management of the density of woody species in grasslands. Although woody encroachment in many instances is a direct consequence of unsustainable management practices, it is unlikely that the introduction of more sustainable practices alone (e.g. the management of fire and grazing regimes) will achieve to restore already degraded areas. Encroached grasslands can constitute a stable state, meaning that without intervention the vegetation will not return to its previous composition.[128] Responsive measures, such as mechanical removal, are needed to restore a different balance between woody and herbaceous plants.[129] Once a high woody plant density is established, woody plants contribute to the soil seed bank more than grasses[130] and the lack of grasses presents less fuel for fires, reducing their intensity.[14] This perpetuates woody encroachment and necessitates intervention, if the encroached state is undesirable for the functions and use of the respective ecosystems. Most interventions constitute a selective thinning of bush densities, although in some contexts also repeat clear-cutting has shown to effectively restore diversity of typical savanna species.[131] In decision making on which woody species to thin out and which to retain, structural and functional traits of the species play a key role.[132]

4.1. Types of Interventions

The term bush control, or brush management, refers to actions that are targeted at controlling the density and composition of bushes and shrubs in a given area. Such measures either serve to reduce risks associated with bush encroachment, such as wildfires, or to rehabilitate the affected ecosystems. It is widely accepted that encroaching indigenous woody plants are to be reduced in numbers, but not eradicated. This is critical as these plants provide important functions in the respective ecosystems, e.g. they serve as habitat for animals.[133][134] Efforts to counter bush encroachment fall into the scientific field of restoration ecology and are primarily guided by ecological parameters, followed by economic indicators. Three different categories of measures can be distinguished:

- Preventive measures: application of proven good management practices to prevent the excessive growth of woody species, e.g. through appropriate stocking rates and rotational grazing in the case of rangeland agriculture.[135] It is generally assumed that preventative measures are a more cost-effective method to combat woody encroachment than treating ecosystems once degradation has occurred.[136]

- Responsive measures: the reduction of bush densities through targeted bush harvesting or other forms of removal (bush thinning).

- Maintenance measures: repeated or continuous measures of maintaining the bush density and composition that has been established through bush thinning.[69]

4.2. Control Methods

Natural bush control

Among others through the introduction of browsers, such as Boer goats,[137] administering controlled fires,[13][138][139][140] or rewilding ecosystems with historic herbivory fauna.[141][142]

Fire was found to be especially effective in reducing bush densities, when coupled with the natural event of droughts[143] or the intentional introduction of browsers.[144][145] Fires have the advantage that they consume the seeds of woody plants in the grass layer before germination, therefore reducing the grasslands sensitivity to encroachment.[146] Prerequisite for successful bush control through fire is sufficient fuel load, thus fires have a higher effectiveness in areas where sufficient grass is available. Furthermore, fires must be administered regularly to address re-growth. Bush control through fire is found to be more effective when applying a range of fire intensities over time.[147] The relation between prescribed fire and tree mortality, is subject of ongoing research.[148]

There is evidence that some rural farming communities have used small ruminants, like goats, to prevent bush encroachment for decades.[149]

Also targeted grazing systems can function as management tool for biodiversity conservation in grasslands. This is subject of ongoing research.[150]

Chemical bush control

Wood densities are frequently controlled through the application of herbicides, in particular arboricides. Frequently applied herbicides are based on the active ingredients tebuthiuron, ethidimuron, bromacil and picloram.[151] In East Africa, first comprehensive experiments on the effectiveness of such bush control date back to 1958–1960.[152]

Mechanical bush control

Cutting or harvesting of bushes and shrubs with manual or mechanised equipment. Mechanical cutting of woody plants is followed by stem-burning, fire or browsing to suppress re-growth.[153] Some studies find that mechanical bush control is more sustainable than controlled fires, because burning leads to deeper soil degradation and faster recovering of shrubs.[154]

4.3. Challenges

Literature emphasizes that a restoration of bush encroached areas to a desired previous non-encroached state is difficult to achieve and the recovery of key-ecosystem may be short-lived or not occur. Intervention methods and technologies must be context specific to achieve their intended outcome.[1][155][156] Current efforts of selective plant removal are found to have slowed or halted woody encroachment in respective areas, but are sometimes found to be outpaced by continuing encroachment.[157][158]

When bush thinning is implemented in isolation, without follow-up measures, grassland may not be rehabilitated. This is because such once-off treatments typically target small areas at a time and they leave plant seeds behind enabling rapid re-establishment of bushes. A combination of preventative measures, addressing the causes of bush encroachment, and responsive measures, rehabilitating affected ecosystems, can overcome bush encroachment in the long-run.[146][159][160]

In grassland conservation efforts, the implementation of measures across networks of private lands, instead of individual farms, remains a key challenge.[157] Due to the high cost of chemical or mechanical removal of woody species, such interventions are often implemented on a small scale, i.e. a few hectares at a time. This differs from natural control processes before human land use, e.g. widespread fires and vegetation pressure by free roaming wildlife. As a result, the interventions often have limited impact on the continued dispersal and spread of woody plants.[139]

Countering woody encroachment can be costly and largely depends on the financial capacity of land users. Linking bush control to the concept of Payment for ecosystem services (PES) has been explored in some countries.[161]

5. Relation to Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

5.1. Consideration in GHG Inventories

Given scientific uncertainties, it varies widely how countries factor woody encroachment and the control thereof into their national Greenhouse Gas Inventories. In early carbon sink quantifications, woody encroachment was found to account for as much as 22% to 40% of the regional carbon sink in the USA,[163][164] while it is considered a key uncertainty in the US carbon balance[165][166] and the sink capacity is found to decrease when encroachment has reached its maximum extent.[167] Also in Australia woody encroachment constitutes a high proportion of the national carbon account.[168][169] In South Africa, woody encroachment was estimated to have added around 21.000 Gg CO2 to the national carbon sink,[170] while it is has been highlighted that especially the loss of grass roots leads to losses of below-ground carbon, which is not fully compensated by gains of above-ground carbon.[171]

It is suggested that the classification of encroached grasslands and savannas as carbon sinks may often be incorrect, underestimating soil organic carbon losses.[91][172]

Beyond difficulties to conclusively quantify the changes in carbon storage, promoting carbon storage through woody encroachment can constitute a trade-off, as it may reduce biodiversity of savanna endemics[47][173] and core ecosystem services, like land productivity and water availability.

Grassland conservation can make a significant contribution to global carbon sequestration targets, but compared to sequestration potential in forestry and agriculture, this is still insufficiently explored and implemented.[174]

5.2. Bush Control as Adaptation Measure

Some countries, for example South Africa, acknowledge inconclusive evidence on the emissions effect of bush thinning, but strongly promote it as a means of climate change adaptation.[175] Geographic selection of intervention areas, targeting areas that are at an early stage of encroachment, can minimise above-ground carbon losses and therewith minimise the possible trade-off between mitigation and adaptation.[176] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reflects on this trade-off: "This variable relationship between the level of encroachment, carbon stocks, biodiversity, provision of water and pastoral value can present a conundrum to policymakers, especially when considering the goals of three Rio Conventions: UNFCCC, UNCCD and UNCBD. Clearing intense bush encroachment may improve species diversity, rangeland productivity, the provision of water and decrease desertification, thereby contributing to the goals of the UNCBD and UNCCD as well as the adaptation aims of the UNFCCC. However, it would lead to the release of biomass carbon stocks into the atmosphere and potentially conflict with the mitigation aims of the UNFCCC." The IPPC further lists bush control as relevant measure under ecosystem-based adaptation and community-based adaptation.[48]

5.3. Grassland Conservation Versus Afforestation

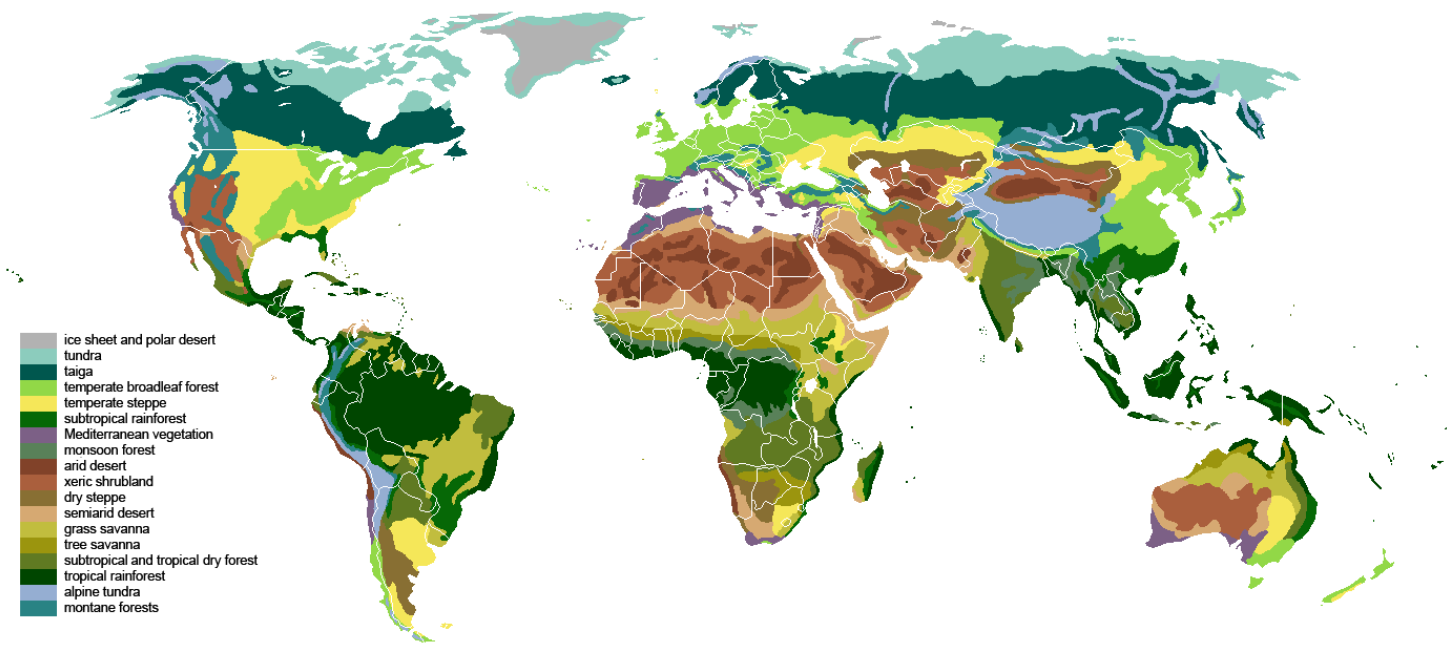

With afforestation having gained popularity as a measure to create or enhance carbon sinks and thereby mitigate global climate change, there are calls to more carefully select suitable ecosystems. Conservation efforts increasingly target grasslands, savannas and open-canopy woodlands, recognising their importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Accepting woody encroachment or the invasion of alien woody species as a measure to mitigate climate change, can have severe negative consequences for the respective ecosystems.[177][178] It is found that grasslands are frequently misidentified as degraded forests and targeted by afforestation efforts.[179] According to an analysis of areas identified to have forest restoration potential by the World Resources Institute, this includes up to 900 million hectares grasslands.[180] In Africa alone, 100 million hectares of grasslands are found to be at risk by misdirected afforestation efforts. Among the areas mapped as degraded forests are the Serengeti and Kruger National Parks, which have not been forested for several million years.[181] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that mitigation action, such as reforestation or afforestation, can encroach on land needed for agricultural adaptation and therewith threaten food security, livelihoods and ecosystem functions.[32]

6. Global Extent

Woody encroachment occurs on all continents in a variety of ecosystems. Its causes, extent and response measures differ and are highly context specific.[182][183]

In sub-Saharan Africa, woody vegetation cover has increased by 8% during the past three decades, mainly through woody encroachment. Overall, 750 million hectares of non-forest biomes experienced significant net gains in woody plant cover, which is more than three times the area that experienced net losses of woody vegetation.[184] In around 249 million hectares of African rangelands long-term climate change was found to be the key driver of vegetation change.[116] In Southern Africa, woody encroachment has been identified as the main factor of greening, i.e. of the increase in vegetation cover detected through remote sensing.[185][186]

In Southern Europe an estimated 8 percent of land area has transitioned from grazing land to woody vegetation between 1950 and 2010.[187]

In the Eurasian Steppe, the largest grassland globally, climate change linked bush encroachment has been found to occur at around 1% per decade.[188]

7. Affected Ecoregions

7.1. Northern Europe

Woody encroachment is common in the Alpine tundra of Norway and Sweden[189][190] Also in the Coastal meadows of Estonia bush encroachment is observed, resulting from land abandonment.[191] In Ireland and Denmark, dry grasslands are affected by woody encroachment. In Ireland extensive low input farming helps to prevent further encroachment by Blackthorn and Hazel, while high density stands are actively thinned out.[192]

7.2. Central Europe and European Alps

Areas that formerly were forests require continuous maintenance to avoid bush encroachment. When active land cultivation ends, fallow land is the result and gradual spread of shrubs and bushes can follow. Animal species once native to Central Europe effectively countered this natural process. These include herbivores such as European bison, auerochs (extinct), red deer and feral horse. Grassland and heath are considered to require protection due to their biodiversity as well as to preserve cultural landscapes. Bush encroachment is therefore frequently countered with selective removal of woody biomass or through the seasonal or year-round introduction of grazing animal species, such as sheep, goats, heck cattle or horses. Bush encroachment occurs in the Alps, where structural change in agriculture leads to the abandonment of land. Alnus viridis is the most widely distributed shrub species in the sub-alpine zone and is found to severely impair species richness and beta diversity when encroaching grassland.[193] Woody encroachment in the alpine tundra is associated with aboveground carbon storage and a slowdown of the biogeochemical cycle.[194] 70 percent of cultivated land in the Eastern Alps are affected by woody encroachment.[195] Also in Hungary bush encroachment is linked to the abandonment of formerly cultivated land. Moderate encroachment is found to have no negative impact on biodiversity and suppression of woody plants is considered an effective restoration approach.[196]

7.3. Mediterranean Basin

The Mediterranean region is widely reported to be affected by bush encroachment. This is found to have negative effects on biodiversity and to magnify climate and related droughts.[197] At the same time encroaching shrubs are also found to have a positive effect, reversing the desertification process.[43][198] Areas experiencing woody encroachment have more extended droughts and higher usage of deep water and this is expected to increase under future climate scenarios.[199] In the Spanish Pyrenees, woody encroachment is connected to land abandonment[200] and affects around 80 percent of cultivated land.[201][202]

7.4. North American Grasslands

North American grasslands have been found to be affected by woody plant encroachment. Documentation of shrub encroachment caused by fire exclusion was documented as early as 1968.[203]

United States of America

In the United States, affected ecosystems include the Chihuahuan Desert, the Sonoran Desert, the northern and southern Rocky Mountains, the sagebrush steppe, as well as the Southern and Central Great Plains. Poor grazing management and fire suppression are among the documented causes.[48][204] Woody plant expansion is considered one of the greatest contemporary threats to mesic grasslands of the central United States.[129] Woody encroachment is estimated to lead to a loss of 75% of potential grass biomass in the Great Plains.[205] In the western US, woody plants have increased on around 44 million hectares since 1999.[206] Among encroaching species is piñon-juniper which mostly encroaches in shrubland adjacent to wooded areas. Up to 350 sagebrush-associated plant and animal species are threatened as a result. In the northern Great Basin piñon-juniper has encroached 0.45 million hectares since 2001 alone.[46] The rate at which grassland is lost to woody encroachment is found to equal the rate of conversion of grassland to agricultural land.[146] Also the tundra ecosystems of Colorado and Alaska areaffected by the rapid expansion of woody shrubs.[207][208]

Negative impacts on forage production and an interrelation with carbon sequestration are documented.[107] At the same time in the semiarid karst savanna of Texas, USA, woody plant encroachment has been found to improve soil infiltrability and therewith groundwater recharge.[209] Over a period of 69 years, woody encroachment in Texas has increase aboveground carbon stocks by 32%.[210] Bird population decline as a result of woody encroachment has been identified as a critical conservation concern,[62] with bird populations found to have decreased by nearly two-thirds over the last half-century.[63]

Through government funded conservation programmes, shrubs and trees are thinned out systematically in affected ecosystems. This is found to revive habitat for birds and improve other ecosystem services.[211] There is evidence that selective thinning with post-treatment has successfully reversed the effects of conifer encroachment in studied areas.[159] At the same time study areas in Nebraska, where Juniperus virginiana encroachment was treated with fire, showed that woody cover stayed low and stable for 8-10 years after fire treatment, but rapid re-encroachment then followed.[212]

7.5. Asian Temperate Savanna and Steppe

China

Temperate savanna-like ecosystems in Northern China are found to be affected by shrub encroachment, linked to unsustainable grazing and climate change.[213] In the Inner Mongolia steppe shrub encroaches steppe.[214]

India

Semi-arid Banni grasslands of western India are found to be affected by bush encroachment, with affects both species composition and behaviour of nocturnal rodents.[215]

7.6. Australian Lowland Woodlands

In Australia woody encroachment is observed across all lowland grassy woodland as well as semi-arid floodplain wetlands and coastal ecosystems, with substantial implications for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services.[216][217]

7.7. Latin American Grasslands

Argentina

In the Gran Chaco intense shrub encroachment has detrimental impact on livestock economies, especially in the Formosa Province. Livestock pressure and the lack of wildfires have been main causes.[218]

Brazil

Wide-ranging woody encroachment is found in the Cerrado, a savannah ecosystem in central Brazil. Studies found that 19% of its area, approximately 17 million hectares, show significant bush encroachment. Among the researched causes are fire suppression and land use abandonment.[219] Fire suppression is linked to Brazil's conservation policy that aims to deforestation in the Amazon, but achieves the limitation of fires also in the Cerrado.[220] This ecological change is linked to the disturbance of ecohydrological processes.[221] In some areas of the Cerrado, open grassland and wetlands has largely disappeared.[222] A contributing factor to the loss of the natural Cerrado savanna ecosystem is the planting of monocultures, such as pine, for wood production. When pine is removed and plantations abandoned, areas turn into low-diversity forests lacking savanna species.[223] Also in the highland grassland of Southern Brazil, bush encroachment caused by land management changes is seen as a significant threat biodiversity, human wellbeing and cultural heritage in grassland ecosystems.[19][224]

Nicaragua

In Nicaragua Vachellia pennatula is known to encroach due to land intensification as well as land abandonment.[225]

7.8. Eastern African Grasslands

Across Eastern Africa, including protected areas, woody encroachment has been noted as a challenge.[226] It has first been documented in the 1970s, with scientists indicating that woody encroachment is the rule rather than the exception in East Africa.[227]

Ethiopia

Grasslands in the Borana Zone in southern Ethiopia are found to be effected by bush encroachment, specifically by Senegalia mellifera, Vachellia reficiens and Vachellia oerfota.[228][229] Woody plants constitute 52% of vegetation cover.[230] This negatively affects species richness and diversity of plant species.[231] Experiments have shown the effectiveness of bush control of different woody species by cutting and stem-burning, cutting with fire-browse combination, cutting and fire as well as cutting and browsing. Post-management techniques were effective in sustaining savanna ecology.[153] In the Bale lowlands, woody encroachment is found to have increased by 546% between 1990 and 2020, transforming grassland into bushland.[232]

Woody encroachment has been found to reduce herbage yield and therewith rangeland productivity.[233] Under woody encroachment, less meat and milk is produced per head of cattle, which challenges traditional pastoral diets.[234][235]

Also the invasive species Prosopis juliflora has expanded rapidly since it was introduced in the 1970s, with direct negative consequences on pasture availability and therewith agriculture. Prosopis is native to Central America and was introduced in an attempt to halt land degradation and provide a source of firewood and animal fodder, but has since then encroached into various ecosystems and become a main driver of degradation.[236] The Afar Region is most severely affected. The wood of the invasive species is commonly used as household fuel in the form of firewood and charcoal.[237][238][239][240]

Shrub encroachment in forest areas of Ethiopia, such as the Desa’a Forest, reduces carbon stocks.[241]

Kenya

In Kenya, woody encroachment has been identified as a main type of land-cover change in grasslands, reducing the grazing availability for pastoralists.[242] Studied areas show an increase of woodland by 39% and a decrease of grassland by 74%, with Vachellia reficiens and Vachellia nubica as a dominant species. Observed causes include overgrazing, suppression of wildfires, the reduction of rain as well as the introduction of bush seeds through smallstock[243][244] Older studies had suggested that an increase in bush cover by 10% reduces grazing by 7%, and grazing is eliminated completely by 90% bush cover.[113] Also Euclea divinorum is a dominant encroaching species.[245] Adaptation strategies include the integration of browsers into the livestock mix, for example goats and camels.[246][247] In areas where Acacia mellifera encroaches, manual bush thinning during the late dry season combined with reseeding of native grasses and soil conservation measures, proved to be an effective restoration measure with 34% improvemetn in perennial grass cover.[248]

In the Baringo County of Kenya, up to 30% of grasslands have disappeared due to the invasion of Prosopis juliflora.[88][249] Clearing Prosopis juliflora to restore grasslands can increase soil organic carbon and generate value through carbon credit schemes.[250]

Tanzania

In Tanzania woody encroachment has been studied in the savanna ecosystem of the Maswa Game Reserve, with detected shrub growth rates of up to 2.6% per annum. Vachellia drepanolobium is dominant species.[251]

Uganda

Bush encroachment in Uganda is found to have negative impacts on livestock farming. In selected study areas farm income was twice as high on farm that implemented bush control, compared to farms with high bush densities.[252][253]

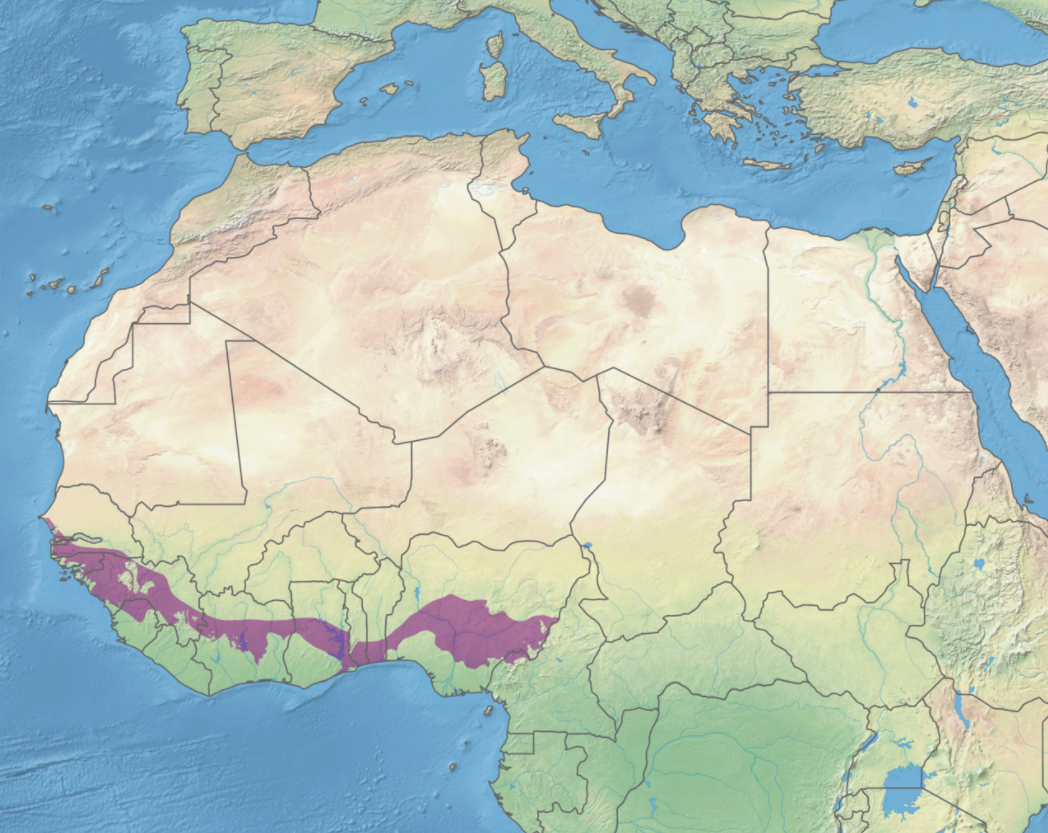

7.9. West African Guinean and Sudanian Savannas

Bush encroachment is observed across several West African countries, especially in the Guinean savanna and the Sudanian savanna.

Ivory Coast

In Ivory Coast late dry season fires were found to reduce bush encroachment in the Guinean savanna.[254]

Cameroon

In Cameroon, among the regions affected by bush encroachment is Adamawa Region, near the Nigerian border. It has been labelled "pastoral thickets" due to the suspected relation to livestock grazing pressure.[255]

Central African Republic

In the 1960s pastroral land in the Central African Republic was mapped and bush encroachment attributed to livestock pressure as well as reduced fire intensity. [255]

7.10. Southern African Savanna

Namibia

Bush encroachment is estimated to affect up to 45 million hectares of savanna in Namibia. As a result, agricultural productivity in Namibia has declined by two-thirds throughout the past decades. The phenomenon affects both commercial and communal farming in Namibia, mostly the central, eastern and north-eastern regions.[256] Common encroacher species include Dichrostachys cinerea, which is most dominant in areas with higher precipitation.[257]

The government of Namibia has recognised bush encroachment as a key challenge for the national economy and food safety. In its current National Development Plan 5, it stipulates that bush shall be thinned on a total of 82.200 hectares per annum.[258] The reduction of bush encroachment on 1.9 million hectares until 2040 is one of Namibia's primary Land Degradation Neutrality Targets under the UNCCD framework.[259] The Government of Namibia pursues a value addition strategy, promoting the sustainable use of bush biomass, which in turn is expected to finance bush harvesting operations. Existing value chains include wood briquettes for household use, woodchips for thermal and electrical energy generation (currently used at Ohorongo Cement factory and at Namibia Breweries Limited), export charcoal, biochar as soil enhancer and animal feed supplement, animal feed, flooring and decking material, predominantly using the invasive species Prosopis, wood carvings, firewood and construction material, i.e. wood composite material.[260]

Increasingly, the encroaching bush is seen as a resource for a biomass industry. Economic assessments were conducted to quantify and value various key ecosystem services and land use options that are threatened by bush encroachment. The evaluation was part of the Economics of Land Degradation (ELD) Initiative,[261] a global initiative established in 2011 by the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, and the European Commission. Based on a national study, cost-benefit analysis suggests a programme of bush control to generate an estimated and aggregated potential net benefit of around N$48.0 billion (USD 3.8 billion) (2015 prices, discounted) over 25 years when compared with a scenario of no bush thinning. This implies a net benefit of around N$2 billion (USD 0.2 billion) (2015 prices, discounted) per annum in the initial round of 25 years.

Namibia has a well-established charcoal sector, which currently comprises approximately 1,200 producers, which employ a total of 10,000 workers. Most producers are farmers, who venture into charcoal production as a means to combat bush encroachment on their land. However, increasingly small enterprises also venture into charcoal making. As per national forestry regulations, charcoal can only be produced from encroaching species. In practice, it however proves difficult to ensure full compliance with these regulations, as the charcoal production is highly decentralised and the inspection capacities of the Directorate of Forestry are low. Voluntary FSC certification has sharply increased in recent years, due to respective demand in many off-take countries, such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany. Due to exclusive use of encroacher bush for charcoal production, rendering the value chain free from deforestation, Namibian charcoal has been dubbed the "greenest charcoal" in an international comparison.[262] In 2016 the Namibia Charcoal Association (NCA) emerged as a legal entity through a restructuring process of the Namibia Charcoal Producers Association, previously attached to Namibia Agricultural Union. It is a non-profit entity and the official industry representation, currently representing an estimated two-thirds of all charcoal producers in the country.

Namibia Biomass Industry Group is a non-profit association under Section 21 of the Companies Act (Act 28 of 2004) of Namibia, founded in 2016. It functions as the umbrella representative body of the emerging bush-based biomass sector in the country with voluntary paid membership. The core objectives, as enlisted in the Articles of Association, include to develop market opportunities for biomass from harvested encroacher bush as well as to address industry bottlenecks, such as skills shortages and research and development needs. The De-bushing Advisory Service is a division of the association, mandated with the dissemination of knowledge on the topics of bush encroachment, bush control and biomass use. Services are provided upon inquiry and are considered a public service and therefore not charged. According to its websites, services include technical advice on bush control and biomass use, environmental advice, the strengthening of existing agricultural outreach services and linkage with service providers.[263] [264]

In 2019, the three Namibian farmers' unions (NNFU, NAU/NLU, NECFU) together with the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry published a best strategy document called "Reviving Namibia's Livestock Industry".[265] The document states that the Namibian livestock industry is in decline due to the loss of palatable perennial grasses and the increase in bush encroachment. Namibia's rangelands show higher levels of bare ground, lower levels of herbaceous cover, lower perennial grass cover, and higher bush densities over large areas. Bush thickening leads to direct competition for moisture with desirable forage species and detrimentally influences the health of the soil. The best practice document identifies tried and tested practices of both emerging and established farmers from communal and title deed farms. These practices include the Split Ranch Approach, several Holistic Management approaches and the Mara Fodder Bank Approach. Other best practices include bush thinning, landscape re-hydration and fodder production. The unions state that there is major scope for enhancing livelihoods through the sustainable use of bush products. In addition, increased profitability and productivity of the sector will have a major impact on the 70% of the Namibian population that depends directly or indirectly on the rangeland resource for their economic well-being and food security.

Both the Forestry Act and the Environmental Act of Namibia govern bush control. Special harvesting permits as well as Environmental Clearance Certificates are applicable to all bush harvesting activities. Responsible Authority is the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism. Effective April 2020 the Forest Stewardship Council introduced a national Namibian FSC standard (National Forest Stewardship Standard) that is closely aligned to the global FSC certification standard, but takes into consideration context specific parameters, such as bush encroachment.[266] In early 2020, the total land area certified under the FSC standard for the purpose of bush thinning and biomass processing was reported to amount to 1.6 million hectares.[267]

Botswana

Bush encroachment in Botswana has been documented from as far back as 1971.[268][269] Around 3.7 million hectares of land in Botswana is affected by bush encroachment, that is over 6% of the total land area. Encroaching species include Acacia tortilis, Acacia erubescens, Acacia mellifera, Dichrostachys cinerea, Grewia flava, and Terminalia sericea.[270] Ecological surveys found bush encroachment affecting both communal grazing areas and private farmland, with particular prevalence in semi-arid ecosystems.[271][272] Encroachment is considered a key form of land degradation, mainly because of the country's significant dependence on agricultural productivity.[161] In selected areas, charcoal production has been introduced as a measure to reduce bush densities.[268][273][274][275]

South Africa

In South Africa bush encroachment entails the abundance of indigenous woody vegetation in grassland and savanna biomes.[126] These biomes make up 27.9% and 32.5% of the land surface area. About 7.3 million hectares are directly affected by bush encroachment, impacting rural communities socio-economically.[276][277] Common encroaching species include Vachellia karoo, Senegalia mellifera, Dichrostachys cinera, Rhus undulata and Rhigozum trichotomum.[278]

Through the public works and conservation programme Working for Water, the government of South Africa allocated approximately 100 million USD per annum for the management of native encroaching species.[279] Land users in South Africa commonly combat woody encroachment through clear felling, burning, intensive browsing or chemical control in the form of herbicide application.[278] Studies have found a positive effect of bush thinning on grass biomass production over short periods of time.[280]

The Kruger National Park is largely affected by bush encroachment, which highlights that global drivers cause encroachment also outside typical rangeland settings.[281]

Lesotho

In 1998, around 16% of Lesotho's rangelands where estimated to be affected by woody encroachment, linked to grazing pressure.[282] Encroaching species include Leucosidea sericea and Chrysocoma and a negative impact of water catchment areas is suspected.[283]

Eswatini

Studies in the Lowveld savannas of Eswatini confirm different heavy woody plant encroachment, especially by Dichrostachys cinerea, among other factors related to grazing pressure. In selected study areas the shrub encroachment increased from 2% in 1947 to 31% in 1990. In some affected areas, frequent fires, coupled with drought, reduced bush densities over time.[143][284]

Zambia

Woody encroachment has been recorded in southern Zambia. Between 1986 and 2010 woody cover increased from 26% to 45% in Kafue Flats and Lochinvar National Park. A common encroacher species is Dichrostachys cinerea.[285]

Zimbabwe

There is evidence of bush encroachment in Zimbabwe, among others by Vachellia karroo.[286] Document notions of woody encroachment in Zimbabwe and its impact on land use date back to 1945.[3][4]

7.11. Other Ecoregions

There is evidence of woody encroachment by Acacia leata, Acacia mellifera, Acacia polyacantha, Acacia senegal and Vachellia seyal in Sudan.[287]

8. Reference Map

The following map displays the countries that are addressed in this article, i.e. countries that feature ecosystems with woody encroachment.

- Purple – Countries with evidence of bush encroachment after land intensification

- Yellow – Countries with evidence of bush encroachment after land abandonment

Template:Highlighted world map by country

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Earth:Bush_encroachment

References

- Van Auken, O.W. (July 2009). "Causes and consequences of woody plant encroachment into western North American grasslands". Journal of Environmental Management 90 (10): 2931–2942. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.04.023. PMID 19501450. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301479709001522.

- Archer, Steve; Boutton, Thomas W.; Hibbard, K.A. (2001), "Trees in Grasslands" (in en), Global Biogeochemical Cycles in the Climate System (Elsevier): pp. 115–137, doi:10.1016/b978-012631260-7/50011-x, ISBN 978-0-12-631260-7, https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B978012631260750011X, retrieved 2021-07-03

- Staples, R.R. 1945. Veld Burning. Rhodesian Agricultural Journal 42, 44-52.

- West, O. (1947). "Thorn bush encroachment in relation to the management of veld grazing". Rhodesian Agricultural Journal 44: 488–497. OCLC 709537921. http://worldcat.org/oclc/709537921.

- Walter, H. (1954). "Die Verbuschung, eine Erscheinung der subtropischen Savannengebiete, und ihre ökologischen Ursachen" (in de). Vegetatio Acta Geobot 5: 6–10. doi:10.1007/BF00299544. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF00299544

- Devine, Aisling P.; McDonald, Robbie A.; Quaife, Tristan; Maclean, Ilya M. D. (2017). "Determinants of woody encroachment and cover in African savannas". Oecologia 183 (4): 939–951. doi:10.1007/s00442-017-3807-6. ISSN 0029-8549. PMID 28116524. Bibcode: 2017Oecol.183..939D. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5348564

- Trollope, W.S.W.; Trollope, Lynne A.; Bosch, O.J.H. (March 1990). "Veld and pasture management terminology in southern Africa". Journal of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa 7 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1080/02566702.1990.9648205. ISSN 0256-6702. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02566702.1990.9648205.

- Moreira, Francisco; Viedma, Olga; Arianoutsou, Margarita; Curt, Thomas; Koutsias, Nikos; Rigolot, Eric; Barbati, Anna; Corona, Piermaria et al. (2011). "Landscape – wildfire interactions in southern Europe: Implications for landscape management". Journal of Environmental Management 92 (10): 2389–2402. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.06.028. PMID 21741757. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301479711002258.

- Zinnert, Julie C.; Nippert, Jesse B.; Rudgers, Jennifer A.; Pennings, Steven C.; González, Grizelle; Alber, Merryl; Baer, Sara G.; Blair, John M. et al. (May 2021). "State changes: insights from the U.S. Long Term Ecological Research Network" (in en). Ecosphere 12 (5). doi:10.1002/ecs2.3433. ISSN 2150-8925. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ecs2.3433.

- Jeltsch, Florian; Milton, Suzanne J.; Dean, W. R. J.; Rooyen, Noel Van (1997). "Analysing Shrub Encroachment in the Southern Kalahari: A Grid-Based Modelling Approach". The Journal of Applied Ecology 34 (6): 1497. doi:10.2307/2405265. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2405265.

- Brown, Joel R.; Archer, Steve (1999). [2385:SIOGRI2.0.CO;2 "Shrub invasion of grassland: recruitment is continuous and not regulated by herbaceous biomass or density."]. Ecology 80 (7): 2385–2396. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[2385:SIOGRI2.0.CO;2]. ISSN 0012-9658. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[2385:SIOGRI]2.0.CO;2.

- O'Connor, Tim G; Puttick, James R; Hoffman, M Timm (4 May 2014). "Bush encroachment in southern Africa: changes and causes". African Journal of Range & Forage Science 31 (2): 67–88. doi:10.2989/10220119.2014.939996. ISSN 1022-0119. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2989/10220119.2014.939996.

- Trollope, W.S.W. (1980). "Controlling bush encroachment with fire in the savanna areas of South Africa". Proceedings of the Annual Congresses of the Grassland Society of Southern Africa 15 (1): 173–177. doi:10.1080/00725560.1980.9648907. ISSN 0072-5560. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00725560.1980.9648907.

- Van Langevelde, Frank; Van De Vijver, Claudius A. D. M.; Kumar, Lalit; Van De Koppel, Johan; De Ridder, Nico; Van Andel, Jelte; Skidmore, Andrew K.; Hearne, John W. et al. (2003). [0337:EOFAHO2.0.CO;2 "Effects of Fire and Herbivory on the Stability of Savanna Ecosystems"]. Ecology 84 (2): 337–350. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0337:EOFAHO2.0.CO;2]. ISSN 0012-9658. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[0337:EOFAHO]2.0.CO;2.

- Archibald, Sally; Roy, David P.; van Wilgen, Brian W.; Scholes, Robert J. (March 2009). "What limits fire? An examination of drivers of burnt area in Southern Africa" (in en). Global Change Biology 15 (3): 613–630. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01754.x. Bibcode: 2009GCBio..15..613A. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01754.x.

- Staver, C.; Archibald, S.; Levin, S.A. (2011). "The Global Extent and Determinants of Savanna and Forest as Alternative Biome States". Science 334 (6053): 230–232. doi:10.1126/science.1210465. PMID 21998389. Bibcode: 2011Sci...334..230S. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1210465

- Lehmann, Caroline E. R.; Archibald, Sally A.; Hoffmann, William A.; Bond, William J. (2011). "Deciphering the distribution of the savanna biome". New Phytologist 191 (1): 197–209. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03689.x. PMID 21463328. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03689.x.

- Ratajczak, Zak; Nippert, Jesse B.; Briggs, John M.; Blair, John M. (2014). Sala, Osvaldo. ed. "Fire dynamics distinguish grasslands, shrublands and woodlands as alternative attractors in the Central Great Plains of North America". Journal of Ecology 102 (6): 1374–1385. doi:10.1111/1365-2745.12311. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/1365-2745.12311.

- Sühs, Rafael Barbizan; Giehl, Eduardo Luís Hettwer; Peroni, Nivaldo (December 2020). "Preventing traditional management can cause grassland loss within 30 years in southern Brazil". Scientific Reports 10 (1): 783. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57564-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 31964935. Bibcode: 2020NatSR..10..783S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6972928

- Schreiner-McGraw, Adam P.; Vivoni, Enrique R.; Ajami, Hoori; Sala, Osvaldo E.; Throop, Heather L.; Peters, Debra P. C. (December 2020). "Woody Plant Encroachment has a Larger Impact than Climate Change on Dryland Water Budgets" (in en). Scientific Reports 10 (1): 8112. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-65094-x. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 32415221. Bibcode: 2020NatSR..10.8112S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=7229153

- Skarpe, Christina (December 1990). "Shrub Layer Dynamics Under Different Herbivore Densities in an Arid Savanna, Botswana". The Journal of Applied Ecology 27 (3): 873–885. doi:10.2307/2404383. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2404383.

- Wigley, Benjamin J.; Bond, William J.; Hoffman, M. Timm (March 2010). "Thicket expansion in a South African savanna under divergent land use: local vs. global drivers?". Global Change Biology 16 (3): 964–976. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02030.x. Bibcode: 2010GCBio..16..964W. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02030.x.

- Bond, W. J.; Midgley, G. F.; Woodward, F. I. (2003). "The importance of low atmospheric CO 2 and fire in promoting the spread of grasslands and savannas". Global Change Biology 9 (7): 973–982. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00577.x. Bibcode: 2003GCBio...9..973B. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00577.x.

- Tabares, Ximena; Zimmermann, Heike; Dietze, Elisabeth; Ratzmann, Gregor; Belz, Lukas; Vieth‐Hillebrand, Andrea; Dupont, Lydie; Wilkes, Heinz et al. (January 2020). "Vegetation state changes in the course of shrub encroachment in an African savanna since about 1850 CE and their potential drivers". Ecology and Evolution 10 (2): 962–979. doi:10.1002/ece3.5955. PMID 32015858. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6988543

- Luvuno, Linda; Biggs, Reinette; Stevens, Nicola; Esler, Karen (2018). "Woody Encroachment as a Social-Ecological Regime Shift". Sustainability 10 (7): 2221. doi:10.3390/su10072221. https://dx.doi.org/10.3390%2Fsu10072221

- Kumar, Dushyant; Pfeiffer, Mirjam; Gaillard, Camille; Langan, Liam; Scheiter, Simon (2 June 2020). "Climate change and elevated CO2 favor forest over savanna under different future scenarios in South Asia". Biogeosciences 18 (9): 2957–2979. doi:10.5194/bg-2020-169. https://bg.copernicus.org/preprints/bg-2020-169/.

- Archer SR; Davies K.W; Fulbright T.E; McDaniel K.C; Wilcox B.P.; Predick K.I (2011). "Brush management as a rangeland conservation strategy: a critical evaluation". Conservation benefits of rangeland practices: assessment, recommendations, and knowledge gaps. Allen Press. ISBN 978-0984949908.

- García Criado, M; Myers‐Smith, IH; Bjorkman, AD; Lehmann, CER; Stevens, N. (May 2020). "Woody plant encroachment intensifies under climate change across tundra and savanna biomes". Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29 (5): 925–943. doi:10.1111/geb.13072. https://www.pure.ed.ac.uk/ws/files/134843317/61._Myers_Smith.pdf.

- Ncisana, Lusanda; Mkhize, Ntuthuko R; Scogings, Peter F (9 May 2021). "Warming promotes growth of seedlings of a woody encroacher in grassland dominated by C 4 species". African Journal of Range & Forage Science: 1–9. doi:10.2989/10220119.2021.1913762. ISSN 1022-0119. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.2989/10220119.2021.1913762.

- Stevens, Nicola; Erasmus, B. F. N.; Archibald, S.; Bond, W. J. (19 September 2016). "Woody encroachment over 70 years in South African savannahs: overgrazing, global change or extinction aftershock?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371 (1703): 20150437. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0437. ISSN 0962-8436. PMID 27502384. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4978877

- Ward, David; Hoffman, M Timm; Collocott, Sarah J (4 May 2014). "A century of woody plant encroachment in the dry Kimberley savanna of South Africa". African Journal of Range & Forage Science 31 (2): 107–121. doi:10.2989/10220119.2014.914974. ISSN 1022-0119. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2989/10220119.2014.914974.

- IPCC, 2018: Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.)]. In Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

- Bora, Zinabu; Wang, Yongdong; Xu, Xinwen; Angassa, Ayana; You, Yuan (July 2021). "Effects comparison of co-occurring Vachellia tree species on understory herbaceous vegetation biomass and soil nutrient: Case of semi-arid savanna grasslands in southern Ethiopia". Journal of Arid Environments 190: 104527. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2021.104527. Bibcode: 2021JArEn.190j4527B. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140196321000938.

- Eldridge DJ, Soliveres S (2014). "Are shrubs really a sign of declining ecosystem function? Disentangling the myths and truths of woody encroachment in Australia.". Australian Journal of Botany 62 (7): 594–608. doi:10.1071/BT14137. https://www.publish.csiro.au/bt/BT14137.

- Eldridge, David J.; Bowker, Matthew A.; Maestre, Fernando T.; Roger, Erin; Reynolds, James F.; Whitford, Walter G. (2011). "Impacts of shrub encroachment on ecosystem structure and functioning: towards a global synthesis". Ecology Letters 14 (7): 709–722. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01630.x. ISSN 1461-0248. PMID 21592276. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3563963

- Maestre, Fernando T.; Eldridge, David J.; Soliveres, Santiago; Kéfi, Sonia; Delgado-Baquerizo, Manuel; Bowker, Matthew A.; García-Palacios, Pablo; Gaitán, Juan et al. (November 2016). "Structure and Functioning of Dryland Ecosystems in a Changing World". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 47 (1): 215–237. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-121415-032311. ISSN 1543-592X. PMID 28239303. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5321561

- Eldridge, David J.; Soliveres, Santiago; Bowker, Matthew A.; Val, James (4 June 2013). "Grazing dampens the positive effects of shrub encroachment on ecosystem functions in a semi-arid woodland". Journal of Applied Ecology 50 (4): 1028–1038. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12105. ISSN 0021-8901. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12105.

- Soliveres, Santiago; Maestre, Fernando T.; Eldridge, David J.; Delgado-Baquerizo, Manuel; Quero, José Luis; Bowker, Matthew A.; Gallardo, Antonio (December 2014). "Plant diversity and ecosystem multifunctionality peak at intermediate levels of woody cover in global drylands: Woody dominance and ecosystem functioning". Global Ecology and Biogeography 23 (12): 1408–1416. doi:10.1111/geb.12215. PMID 25914607. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4407977

- Riginos, Corinna; Grace, James B.; Augustine, David J.; Young, Truman P. (November 2009). "Local versus landscape-scale effects of savanna trees on grasses". Journal of Ecology 97 (6): 1337–1345. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01563.x. ISSN 0022-0477. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01563.x.

- Knapp, Alan K.; Briggs, John M.; Collins, Scott L.; Archer, Steven R.; Bret-Harte, M. Syndonia; Ewers, Brent E.; Peters, Debra P.; Young, Donald R. et al. (2008). "Shrub encroachment in North American grasslands: shifts in growth form dominance rapidly alters control of ecosystem carbon inputs: SHRUB ENCROACHMENT INTO GRASSLANDS ALTERS CARBON INPUTS". Global Change Biology 14 (3): 615–623. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01512.x. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01512.x.

- Conant, F. (1982). Thorns paired, sharply recurved: Cultural controls and rangeland quality in East Africa. In Spooner, B., and Mann, H. (eds.), Desertification and Development; Dryland Ecology in Social Perspective. Academic Press, London.

- Asner, Gregory P.; Elmore, Andrew J.; Olander, Lydia P.; Martin, Roberta E.; Harris, A. Thomas (21 November 2004). "Grazing Systems, Ecosystem Responses, and Global Change" (in en). Annual Review of Environment and Resources 29 (1): 261–299. doi:10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102142. ISSN 1543-5938. http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.energy.29.062403.102142.

- Maestre, Fernando T.; Bowker, Matthew A.; Puche, María D.; Belén Hinojosa, M.; Martínez, Isabel; García-Palacios, Pablo; Castillo, Andrea P.; Soliveres, Santiago et al. (September 2009). "Shrub encroachment can reverse desertification in semi-arid Mediterranean grasslands" (in en). Ecology Letters 12 (9): 930–941. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01352.x. PMID 19638041. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01352.x.

- Smit, G.N. (2005). "Tree thinning as an option to increase herbaceous yield of an encroached semi-arid savanna in South Africa.". BMC Ecol 5: 4. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-5-4. PMID 15921528. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1164409

- Stanton RA Jr; Boone Iv WW; Soto-Shoender J; Fletcher RJ Jr; Blaum N; McCleery RA (2018). "Shrub encroachment and vertebrate diversity: a global meta-analysis". Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27 (3): 368–379. doi:10.1111/geb.12675. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fgeb.12675

- "Cutting Trees Gives Sage-Grouse Populations a Boost, Scientists Find" (in en). 2021-06-10. https://www.audubon.org/news/cutting-trees-gives-sage-grouse-populations-boost-scientists-find.

- "The biodiversity cost of carbon sequestration in tropical savanna.". Science Advances 3: e1701284 (8): e1701284. 2017. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1701284. PMID 28875172. Bibcode: 2017SciA....3E1284A. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5576881

- IPCC, 2019: Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems, P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. Neogi, M. Pathak, J. Petzold, J. Portugal Pereira, P. Vyas, E. Huntley, K. Kissick, M. Belkacemi, J. Malley, (eds.). In press. https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/

- Schooley, Robert L.; Bestelmeyer, Brandon T.; Campanella, Andrea (July 2018). "Shrub encroachment, productivity pulses, and core-transient dynamics of Chihuahuan Desert rodents" (in en). Ecosphere 9 (7): e02330. doi:10.1002/ecs2.2330. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ecs2.2330.

- Mogashoa, R.; Dlamini, P.; Gxasheka, M. (2020). "Grass species richness decreases along a woody plant encroachment gradient in a semi-arid savanna grassland, South Africa.". Landscape Ecol 36 (2): 617–636. doi:10.1007/s10980-020-01150-1. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10980-020-01150-1

- Ratajczak, Z.; Nippert, J.; Collins, S. (2012). "Woody encroachment decreases diversity across North American grasslands and savannas.". Ecology 93 (4): 697–703. doi:10.1890/11-1199.1. PMID 22690619. https://dx.doi.org/10.1890%2F11-1199.1

- Barbara I. Bleho; Christie L. Borkowsky; Melissa A. Grantham; Cary D. Hamel (2021). "A 20 y Analysis of Weather and Management Effects on a Small White Lady's-slipper (Cypripedium candidum) Population in Manitoba". The American Midland Naturalist 185 (1): 32–48. doi:10.1637/0003-0031-185.1.32. https://dx.doi.org/10.1637%2F0003-0031-185.1.32

- She, W.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, Y. (2021). "Nitrogen-enhanced herbaceous competition threatens woody species persistence in a desert ecosystem". Plant Soil 460 (1–2): 333–345. doi:10.1007/s11104-020-04810-y. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11104-020-04810-y