Proto-Norse (also called Proto-Scandinavian, Proto-Nordic, Ancient Scandinavian, Proto-North Germanic and a variety of other names) was an Indo-European language spoken in Scandinavia that is thought to have evolved as a northern dialect of Proto-Germanic in the first centuries CE. It is the earliest stage of a characteristically North Germanic language, and the language attested in the oldest Scandinavian Elder Futhark inscriptions, spoken from around the 2nd to the 8th centuries CE (corresponding to the late Roman Iron Age and the Germanic Iron Age). It evolved into the dialects of Old Norse at the beginning of the Viking Age around 800 CE, which later themselves evolved into the modern North Germanic languages (Faroese, Icelandic, the three Continental Scandinavian languages, and their dialects).

- scandinavia

- proto-norse

- proto-scandinavian

1. Phonology

Proto-Norse phonology probably did not differ substantially from that of Proto-Germanic. Although the phonetic realisation of several phonemes had probably changed over time (as with any language), the overall system of phonemes and their distribution remained largely unchanged.

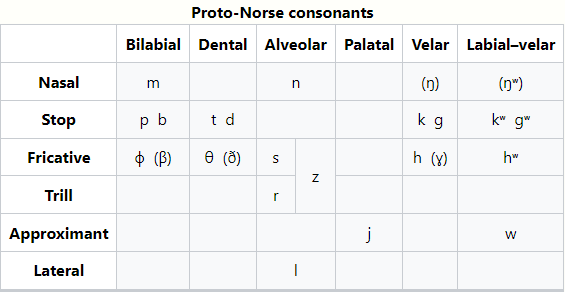

1.1. Consonants

- /n/ assimilated to a following velar consonant. It was [ŋ] before a plain velar, and probably [ŋʷ] before a labial-velar consonant.

- Unlike its Proto-Germanic ancestor /x/, the phoneme /h/ was probably no longer a fricative. It eventually disappeared except word-initially.

- [β], [ð] and [ɣ] were allophones of /b/, /d/ and /ɡ/, and occurred in most word-medial positions. Plosives appeared when the consonants were lengthened (geminated), and also after a nasal consonant. Word-finally, [b], [d] and [ɡ] were devoiced and merged with /p/, /t/, /k/.

- The exact realisation of the phoneme /z/, traditionally written as ʀ in transcriptions of runic Norse (not to be confused with the phonetic symbol /ʀ/), is unclear. While it was a simple alveolar sibilant in Proto-Germanic (as in Gothic), it eventually underwent rhotacization and merged with /r/ towards the end of the runic period. It may have been pronounced as [ʒ] or [ʐ], tending towards a trill in the later period. The sound was still written with its own letter in runic Old East Norse around the end of the millennium.

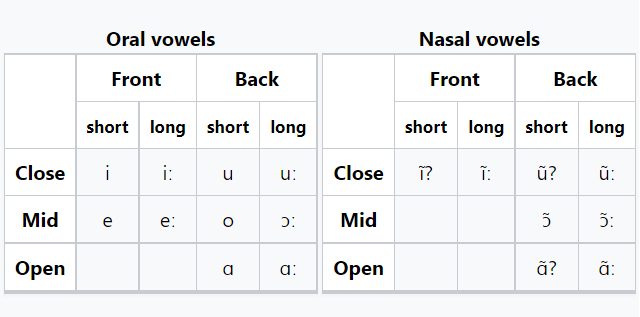

1.2. Vowels

The system of vowels differed somewhat more from that of Proto-Germanic than the consonants. Earlier /ɛː/ had been lowered to /ɑː/, and unstressed /ɑi/ and /ɑu/ had developed into /eː/ and /ɔː/. Shortening of word-final vowels had eliminated the Proto-Germanic overlong vowels.

- /o/ had developed from /u/ through a-mutation. It also occurred word-finally as a result of the shortening of Proto-Germanic /ɔː/.

- The long nasal vowels /ɑ̃ː/, /ĩː/ and /ũː/ occurred only before /h/. Their presence was noted in the 12th century First Grammatical Treatise, and they survive in modern Elfdalian.

- All other nasal vowels occurred only word-finally, although it is unclear whether they had retained their nasality in Proto-Norse or had already merged with the oral vowels. The vowels /o/ and /ɔ̃/ were contrastive, however, as the former eventually developed into /u/ (triggering u-mutation) while the latter was lowered to /ɑ/.

- The back vowels probably had central or front allophones when /i/ or /j/ followed, as a result of i-mutation:

- /ɑ/ > [æ], /ɑː/ > [æː]

- /u/ > [ʉ], /uː/ > [ʉː] (later /y/, /yː/)

- /ɔː/ > [ɞː] (later [œː] or [øː])

- /o/ did not originally occur before /i/ or /j/, but it was later introduced by analogy (as can be seen on the Gallehus horns). Its allophone was probably [ɵ], later [ø].

- Towards the end of the Proto-Norse period, stressed /e/ underwent breaking, becoming a rising diphthong /jɑ/.

- Also towards the end of the Proto-Norse period, u-mutation began to take effect, which created rounded allophones of unrounded vowels.

1.3. Diphthongs

At least the following diphthongs were present: /æi/, /ɑu/, /eu/, /iu/.

- /ɑu/ was later rounded to /ɒu/ due to u-mutation.

- /eu/ eventually underwent breaking to become the triphthong /jɒu/. This was preserved in Old Gutnish, but simplified to a long rising /joː/ or /juː/ in other areas.

- As /iu/ occurred exclusively in environments with i-mutation, its realisation was probably fronted [iʉ]. This then developed further into [iy], which then became /yː/.

1.4. Accent

Old Norse had a stress accent which fell on the first syllable. Several scholars have proposed that Proto-Norse also had a separate pitch accent, which was inherited from Proto-Indo-European and has evolved into the tonal accents of modern Swedish and Norwegian, which in turn have evolved into the stød of modern Danish.[1][2] Another recently advanced theory is that each Proto-Norse long syllable and every other short syllable received stress, marked by pitch, eventually leading to the development of the Swedish and Norwegian tonal accent distinction.[3] Finally, quite a number of linguists have assumed that even the first phonetic rudiments of the distinction did not appear until the Old Norse period.[4][5][6][7]

2. Attestations

2.1. Runic Inscriptions

The surviving examples of Proto-Norse are all runic inscriptions in the Elder Futhark. There are about 260 surviving Elder Futhark inscriptions in Proto-Norse, the earliest dating to the 2nd century.

Examples

- Øvre Stabu spearhead, Oppland, Norway. Second century raunijaz, ON raun "tester", cf. Norwegian røyne "try, test". Swedish utröna "find out". The word formation with a suffix ija is evidence of Sievers' law.

- Golden Horn of Gallehus 2, South Jutland, Denmark 400 CE, ek hlewagastiz holtijaz horna tawido, "I, Hlewagastis of Holt, made the horn." Note again the ija suffix

- Tune stone, Østfold, Norway, 400 CE. ek wiwaz after woduride witadahalaiban worahto. [me]z woduride staina þrijoz dohtriz dalidun arbija sijostez arbijano, I Wiwaz, after Woduridaz bread-warden wrought. For me Woduridaz, the stone, three daughters prepared, the most noble of heirs.

- The Einang stone, near Fagernes, Norway, is dated to the 4th century. It contains the message [ek go]dagastiz runo faihido ([I, Go]dguest drew the secret), in O-N ek goðgestr rún fáða. The first four letters of the inscription have not survived and are conjectured, and the personal name could well have been Gudagasti or something similar.

- Kragehul spear, Denmark, c. 500 CE. ek erilaz asugisalas muha haite, gagaga ginuga, he...lija... hagala wijubi... possibly, "I, Eril of Asgisl, was named Muha, ga-ga-ga mighty-ga (ga being most likely an abbreviation of indeterminable reference), (incomplete) hail I consecrate."

- The Björketorp Runestone, Blekinge, Sweden, is one of three menhirs, but is the only one of them where, in the 6th century, someone wrote a curse: haidz runo runu falh'k hedra ginnarunaz argiu hermalausz ... weladauþe saz þat brytz uþarba spa (Here, I have hidden the secret of powerful runes, strong runes. The one who breaks this memorial will be eternally tormented by anger. Treacherous death will hit him. I foresee perdition.)

- The Rö runestone, in Bohuslän, Sweden, was raised in the early 5th century and is the longest early inscription: Ek Hrazaz/Hraþaz satido [s]tain[a] ... Swabaharjaz s[a]irawidaz. ... Stainawarijaz fahido. "I, Hrazaz/Hraþaz raised the stone ... Swabaharjaz with wide wounds. ... Stainawarijaz (Stoneguardian's) carved."

2.2. Loanwords

Numerous early Germanic words have survived largely unchanged as borrowings in Finnic languages. Some of these may be of Proto-Germanic origin or older still, but others reflect developments specific to Norse. Some examples (with the reconstructed Proto-Norse form):

- Estonian/Finnish kuningas < *kuningaz "king" (Old Norse kunungr, konungr)

- Finnish ruhtinas "prince" < *druhtinaz "lord" (Old Norse dróttinn)

- Finnish sairas "sick" < *sairaz "sore" (Old Norse sárr)

- Estonian juust, Finnish juusto "cheese" < *justaz (Old Norse ostr)

- Estonian/Finnish lammas "sheep" < *lambaz "lamb" (Old Norse lamb)

- Finnish hurskas "pious" < *hurskaz "prudent, wise, quick-minded" (Old Norse horskr)

- Finnish runo "poem, rune" < *rūno "secret, mystery, rune" (Old Norse rún)

- Finnish vaate "garment" < *wādiz (Old Norse váð)

- Finnish viisas "wise" < *wīsaz (Old Norse víss)

A very extensive Proto-Norse loanword layer also exists in the Sami languages.[8][9]

2.3. Other

Some Proto-Norse names are found in Latin works, like tribal names like Suiones (*Sweoniz, "Swedes"). Others can be conjectured from manuscripts such as Beowulf.

3. Evolution

3.1. Proto-Germanic to Proto-Norse

The differences between attested Proto-Norse and unattested Proto-Germanic are rather small. Separating Proto-Norse from Northwest Germanic can be said to be a matter of convention, as sufficient evidence from the remaining parts of the Germanic-speaking area (Northern Germany and the Netherlands) is lacking in a degree to provide sufficient comparison. Inscriptions found in Scandinavia are considered to be in Proto-Norse. Several scholars argue about this subject matter. Wolfgang von Krause sees the language of the runic inscriptions of the Proto-Norse period as an immediate precursor to Old Norse, but Elmer Antonsen views them as Northwest Germanic,[10] but his views on Runic Script and related subjects might be considered extreme.

One early difference shared by the West Germanic dialects is the monophthongization of unstressed diphthongs. Unstressed *ai became ē, as in haitē (Kragehul I) from Proto-Germanic *haitai, and unstressed *au likewise became ō. Characteristic is also the Proto-Norse lowering of Proto-Germanic stressed ē to ā, which is demonstrated by the pair Gothic mēna and Old Norse máni (English moon). Proto-Norse thus differs from the early West Germanic dialects, as West Germanic ē was lowered to ā regardless of stress; in Old Norse, earlier unstressed ē surfaces as i. For example, the weak third-person singular past tense ending -dē appears in Old High German as -ta, with a low vowel, but in Old Norse as -ði, with a high vowel.

The time that *z, a voiced apical alveolar fricative, represented in runic writing by the algiz rune, changed to ʀ, an apical post-alveolar approximant, is debated. If the general Proto-Norse principle of devoicing of consonants in final position is taken into account, *z, if retained, would have been devoiced to [s] and would be spelled as such in runes. There is, however, no trace of that in the Elder Futhark runic inscriptions, so it can be safely assumed that the quality of this consonant must have changed before the devoicing, or the phoneme would not have been marked with a rune different from the sowilō rune used for s. The quality of the consonant can be conjectured, and the general opinion is that it was something between [z] and [r], the Old Norse reflex of the sound. In Old Swedish, the phonemic distinction between r and ʀ was retained into the 11th century, as shown by the numerous runestones from Sweden from then.

3.2. Proto-Norse to Old Norse

From 500 to 800, two great changes occurred within Proto-Norse. Umlauts appeared, which means that a vowel was influenced by the succeeding vowel or semivowel: Old Norse gestr (guest) came from P-N gastiz (guest). Another sound change is known as vowel breaking in which the vowel changed into a diphthong: hjarta from *hertō or fjǫrðr from *ferþuz.

Umlauts resulted in the appearance of the new vowels y (like fylla from *fullijaną) and œ (like dœma from *dōmijaną). The umlauts are divided into three categories, A-umlaut, i-umlaut and u-umlaut; the last was still productive in Old Norse. The first, however, appeared very early, and its effect can be seen already around 500, on the Golden Horns of Gallehus.[11] The variation caused by the umlauts was itself no great disruption in the language. It merely introduced new allophones of back vowels if certain vowels were in following syllables. However, the changes brought forth by syncope made the umlaut-vowels a distinctive non-transparent feature of the morphology and phonology, phonemicising what were previously allophones.

Syncope shortened the long vowels of unstressed syllables; many shortened vowels were lost. Also, most short unstressed vowels were lost. As in P–N, the stress accent lay on the first syllable words as P–N *katilōz became ON katlar (cauldrons), P–N horną was changed into Old Norse horn and P–N gastiz resulted in ON gestr (guest). Some words underwent even more drastic changes, like *habukaz which changed into ON haukr (hawk).

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Social:Proto-Norse_language

References

- Kock, Axel, 1901: Die alt- und neuschwedische Akzentuierung. Quellen und Forschungen 87. Strassburg

- Hamp, Eric P., 1959: Final syllables in Germanic and the Scandinavian accent system. I: Studia Linguistica 13. S.29–48.

- Riad, Tomas, 1998: The origin of Scandinavian tone accents. I: Diachronica XV(1). S.63–98.

- Kristoffersen, Gjert, 2004: The development of tonal dialects in the Scandinavian languages. Analysis based on presentation at ESF-workshop 'Typology of Tone and Intonation', Cascais, Portugal 1–3 April 2004. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110717233112/http://helmer.hit.uib.no/NTT/Cascais/0404ManusCascaisRevised.htm. Retrieved 2007-12-02. .

- Elstad, Kåre, 1980: Some Remarks on Scandinavian Tonogenesis. I: Nordlyd: Tromsø University Working Papers on Language and Linguistics 3. 61–77.

- Öhman, Sven, 1967: Word and sentence intonation: a quantitative model. Speech Transmission Laboratory Quarterly Progress and Status Report, KTH, 2–3. 20–54, 1967., 8(2–3):20–54.[1]

- Bye, Patrick, 2004: Evolutionary typology and Scandinavian pitch accent. Kluwer Academic Publishers. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080410051839/http://www.hum.uit.no/a/bye/Papers/pitch-accent-kluw.pdf. Retrieved 2007-12-02. .

- Theil, Rolf (2012). "Urnordiske lån i samisk". in Askedal, John Ole; Schmidt, Tom; Theil, Rolf (in no). Germansk filologi og norske ord. Festskrift til Harald Bjorvand på 70-årsdagen den 30. juli 2012. Oslo: Novus forlag. https://www.academia.edu/8439830/Urnordiske_l%C3%A5n_i_samisk. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Aikio, Ante (2012). Grünthal, Riho; Kallio, Petri. eds. "An Essay on Saami Ethnolinguistic Prehistory". Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne (Helsinki: Finno-Ugrian Society) (266, A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe): 76. http://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust266/sust266_aikio.pdf.

- Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung, "The linguistic status of the Early Runic Inscriptions", Hans Frede Nielsen, Walter de Gruyter GmBH & Co. KG 1998, ISBN:3-11-015455-2

- Spurkland, Terje (2005). Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-186-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=1QDKqY-NWvUC.