A peach is a soft, juicy and fleshy stone fruit produced by a peach tree.

- peach

- stone fruit

1. History

Peaches were cultivated in China as far back as 8,000 years ago, with domestication at least 4,000 years ago. Some sources claim that peaches originated in China,[1] whilst others claim that it originated in Iran.[2]

2. Varieties

Hundreds of peach and nectarine cultivars are known. These are classified into two categories — the freestones and the clingstones, depending on whether the flesh sticks to the stone or not. Freestones are those whose flesh separates readily from the pit. Clingstones are those whose flesh clings tightly to the pit. Some cultivars are partially freestone and clingstone, so are called semifree. Freestone types are preferred for eating fresh, while clingstone types are for canning. The fruit flesh may be creamy white to deep yellow, to dark red; the hue and shade of the color depends on the cultivar.[3]

Peaches with white flesh typically are very sweet with little acidity, while yellow-fleshed peaches typically have an acidic tang coupled with a sweet floral taste (sometimes described as the classic peach taste, which mellows as the peach ripens and softens), red fleshed varieties are typically flavourful and tangy but with a tart skin,[4] though this also varies greatly. Yellow peaches have a sturdier flesh that is not as easily bruised.[5] Both colors often have some red on their skin. Low-acid white-fleshed peaches are the most popular kinds in China, Japan, and neighbouring Asian countries, while Europeans and North Americans have historically favoured the acidic, yellow-fleshed cultivars.[6]

Peach breeding has favored cultivars with more firmness, more red color, and shorter fuzz on the fruit surface. These characteristics ease shipping and improve supermarket sales due to eye appeal. However, this selection process has not necessarily led to increased flavor. Peaches have a short shelf life, so commercial growers typically plant a mix of different cultivars to have fruit to ship all season long.[7]

2.1. Nectarine

The variety P. persica var. nucipersica (or var. nectarina), commonly called nectarine, has a smooth skin. It is on occasion referred to as a "shaved peach" or "fuzzless peach", due to its lack of fuzz or short hairs. Though fuzzy peaches and nectarines are regarded commercially as different fruits, with nectarines often erroneously believed to be a crossbreed between peaches and plums, or a "peach with a plum skin", nectarines belong to the same species as peaches. Several genetic studies have concluded nectarines are produced due to a recessive allele, whereas a fuzzy peach skin is dominant.[8] Nectarines have arisen many times from peach trees, often as bud sports.

As with peaches, nectarines can be white or yellow, and clingstone or freestone. On average, nectarines are slightly smaller and sweeter than peaches, but with much overlap.[8] The lack of skin fuzz can make nectarine skins appear more reddish than those of peaches, contributing to the fruit's plum-like appearance. The lack of down on nectarines' skin also means their skin is more easily bruised than peaches.

The history of the nectarine is unclear; the first recorded mention in English is from 1616,[9] but they had probably been grown much earlier within the native range of the peach in central and eastern Asia. Although one source states that nectarines were introduced into the United States by David Fairchild of the Department of Agriculture in 1906,[10] a number of colonial-era newspaper articles make reference to nectarines being grown in the United States prior to the Revolutionary War. 28 March 1768 edition of the New York Gazette (p. 3), for example, mentions a farm in Jamaica, Long Island, New York, where nectarines were grown.

| Peach production, 2017 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations [11] | |||

2.2. Peacherines

Peacherine is claimed to be a cross between a peach and a nectarine, and are marketed in Australia and New Zealand. The fruit is intermediate in appearance between a peach and a nectarine, large and brightly colored like a red peach. The flesh of the fruit is usually yellow, but white varieties also exist. The Koanga Institute lists varieties that ripen in the Southern Hemisphere in February and March.[12][13]

In 1909, Pacific Monthly mentioned peacherines in a news bulletin for California. Louise Pound, in 1920, claimed the term peacherine is an example of language stunt.[14]

2.3. Flat Peaches

Flat peaches or pan-tao have a flattened shape in contrast to ordinary rounded peaches.[15]

3. Production

In 2017, world production of peaches was 24.7 million tonnes, led by China with 58% of the total. Spain and Italy each produced more than one million tonnes.

4. Nutrition

Raw peach flesh is 89% water, 10% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and contains negligible fat. A medium raw peach, weighing 100 g (3.5 oz), supplies 39 calories, and contains small amounts of essential nutrients, but none is a significant proportion of the Daily Value (DV, right table). A raw nectarine has similar low content of nutrients.[16] The glycemic load of an average peach (120 grams) is 5, similar to other low-sugar fruits.[17]

5. Phytochemicals

Total polyphenols in mg per 100 g of fresh weight were 14–102 in white-flesh nectarines, 18–54 in yellow-flesh nectarines, 28–111 in white-flesh peaches, and 21–61 mg per 100 g in yellow-flesh peaches.[18] The major phenolic compounds identified in peach are chlorogenic acid, catechins and epicatechins,[19] with other compounds, identified by HPLC, including gallic acid and ellagic acid.[20] Rutin and isoquercetin are the primary flavonols found in clingstone peaches.[21]

Red-fleshed peaches are rich in anthocyanins,[22] particularly cyanidin glucosides in six peach and six nectarine cultivars[23] and malvin glycosides in clingstone peaches.[21] As with many other members of the rose family, peach seeds contain cyanogenic glycosides, including amygdalin (note the subgenus designation: Amygdalus). These substances are capable of decomposing into a sugar molecule and hydrogen cyanide gas.[24] While peach seeds are not the most toxic within the rose family (see bitter almond), large consumption of these chemicals from any source is potentially hazardous to animal and human health.[24]

Peach allergy or intolerance is a relatively common form of hypersensitivity to proteins contained in peaches and related fruits (such as almonds). Symptoms range from local effects (e.g. oral allergy syndrome, contact urticaria) to more severe systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis (e.g. urticaria, angioedema, gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms).[25] Adverse reactions are related to the "freshness" of the fruit: peeled or canned fruit may be tolerated.

5.1. Aroma

Some 110 chemical compounds contribute to peach aroma, including alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, esters, polyphenols and terpenoids.[26]

6. Peaches in Art

-

Girl with Peaches

Valentin Serov

1887 -

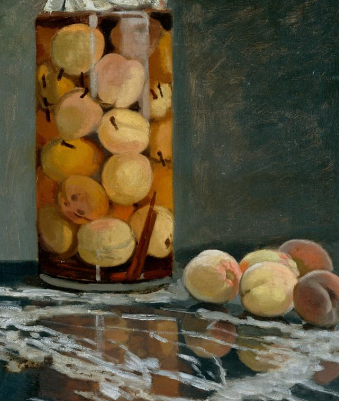

Jar of Peaches

Claude Monet

1866 -

Still Life Basket of Peaches

Raphaelle Peale

1816. -

Portrait of Isabella and John Stewart

Charles Willson Peale

1774.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biology:Peach_(fruit)

References

- "peach | Fruit, Description, & Facts" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/plant/peach. "The peach probably originated in China and then spread westward through Asia to the Mediterranean countries and later to other parts of Europe."

- Albala, Ken (2011) (in en). Food Cultures of the World Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-313-37626-9. https://books.google.fr/books?id=NTo6c_PJWRgC&pg=PA240&lpg=PA240&dq=lavash+originated+iran&source=bl&ots=gjAWpULyc4&sig=ACfU3U2NGVzGDhXoF-OdH5yuP-DEpZ-I-A&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi6v8COs_XoAhWN5OAKHeuqASM4HhDoATAGegQIDBAx#v=onepage&q=lavash%20originated%20iran&f=false.

- "Peach and Nectarine Culture". University of Rhode Island. 2000. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130114152342/http://www.uri.edu/ce/factsheets/sheets/peaches.html.

- https://www.thekitchn.com/whats-the-difference-white-and-1-120174

- https://www.cooksillustrated.com/how_tos/11454-yellow-peaches-versus-white-peaches

- https://www.thespruceeats.com/varieties-of-peaches-4057064

- Okie, W.R. (2005). "Varieties – Peaches". United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 14 January 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130114152347/http://www.ent.uga.edu/peach/peachhbk/preplant/varieties.pdf.

- Oregon State University: peaches and nectarines https://web.archive.org/web/20080714065820/http://food.oregonstate.edu/faq/uffva/nectarine2.html

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Fairchild, David (1938). The World Was My Garden. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 226. https://archive.org/details/worldwasmygarden00fair.

- "Peach and nectarine production in 2017, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2017. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Almonds, Nectarines, Peacherines and Apricots". Koanga Institute. Archived from the original on 15 February 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140215091505/http://koanga.org.nz/knowledgebase/fruit-tree-knowledge/fruit-tree-collection/almonds-nectarines-peacherines-and-apricots/. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Shimabukuro, Betty (7 July 2004). "Mixed marriages: Cross-pollination produces fruit "children" that aren't quite the same as mom and dad". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120302215633/http://archives.starbulletin.com/2004/07/07/features/story1.html. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- Pound, Louise (1920). "Stunts in language". The English Language 9 (2): 88–95.

- Layne, Desmond (2008). The Peach: Botany, Production and uses. CABI. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-84593-386-9. https://books.google.com/?id=Ak2YiPi20d4C&lpg=PA16&dq=flat%20saucer%20pan-tao%20peach&pg=PA16#v=onepage&q=flat%20saucer%20pan-tao%20peach&f=false. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- "Nutrition Facts for Nectarines, raw, per 100 g". Conde Nast, USDA National Nutrient Database, version SR-21. 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150315230637/http://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/fruits-and-fruit-juices/1962/2. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Glycemic index and glycemic load for 100+ foods". Harvard Health Publications, Harvard University School of Medicine. 27 August 2015. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. https://web.archive.org/web/20170425133931/http://www.health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/glycemic_index_and_glycemic_load_for_100_foods. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Gil, M. I.; Tomás-Barberán, F. A.; Hess-Pierce, B.; Kader, A. A. (2002). "Antioxidant capacities, phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and vitamin C contents of nectarine, peach, and plum cultivars from California". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 50 (17): 4976–4982. doi:10.1021/jf020136b. PMID 12166993. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjf020136b

- Cheng, Guiwen W.; Crisosto, Carlos H. (1995). "Browning Potential, Phenolic Composition, and Polyphenoloxidase Activity of Buffer Extracts of Peach and Nectarine Skin Tissue". J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 120 (5): 835–838. doi:10.21273/JASHS.120.5.835. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140514064211/http://journal.ashspublications.org/content/120/5/835.full.pdf. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- Infante, Rodrigo; Contador, Loreto; Rubio, Pía; Aros, Danilo; Peña-Neira, Álvaro (2011). "Postharvest sensory and phenolic characterization of 'Elegant Lady' and 'Carson' peaches". Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research 71 (3): 445–451. doi:10.4067/S0718-58392011000300016. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120711213119/http://www.scielo.cl/pdf/chiljar/v71n3/at16.pdf.

- Chang, S; Tan, C; Frankel, EN; Barrett, DM (2000). "Low-density lipoprotein antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds and polyphenol oxidase activity in selected clingstone peach cultivars". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 48 (2): 147–51. doi:10.1021/jf9904564. PMID 10691607. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fjf9904564

- Cevallos-Casals, B. V. A.; Byrne, D.; Okie, W. R.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. (2006). "Selecting new peach and plum genotypes rich in phenolic compounds and enhanced functional properties". Food Chemistry 96 (2): 273–280. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.02.032. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.foodchem.2005.02.032

- Andreotti, C.; Ravaglia, D.; Ragaini, A.; Costa, G. (2008). "Phenolic compounds in peach (Prunus persica) cultivars at harvest and during fruit maturation". Annals of Applied Biology 153: 11–23. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00234.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1744-7348.2008.00234.x

- Cho HJ, Do BK, Shim SM, Kwon H, Lee DH, Nah AH, Choi YJ, Lee SY (2013). "Determination of cyanogenic compounds in edible plants by ion chromatography". Toxicol Res 29 (2): 143–7. doi:10.5487/TR.2013.29.2.143. PMID 24278641. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3834451

- Besler, M.; Cuesta Herranz, Javier; Fernandez-Rivas, Montserrat (2000). "Allergen Data Collection: Peach (Prunus persica)". Internet Symposium on Food Allergens 2 (4): 185–201. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090817132607/http://www.food-allergens.de/symposium-2-4/peach/peach-allergens.htm.

- Sánchez G, Besada C, Badenes ML, Monforte AJ, Granell A (2012). "A non-targeted approach unravels the volatile network in peach fruit". PLoS ONE 7 (6): e38992. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038992. PMID 22761719. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...738992S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3382205