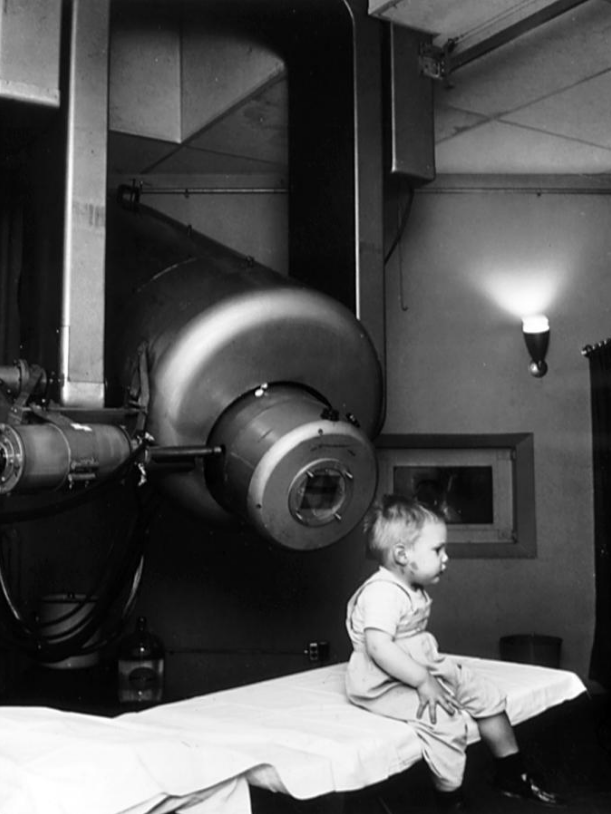

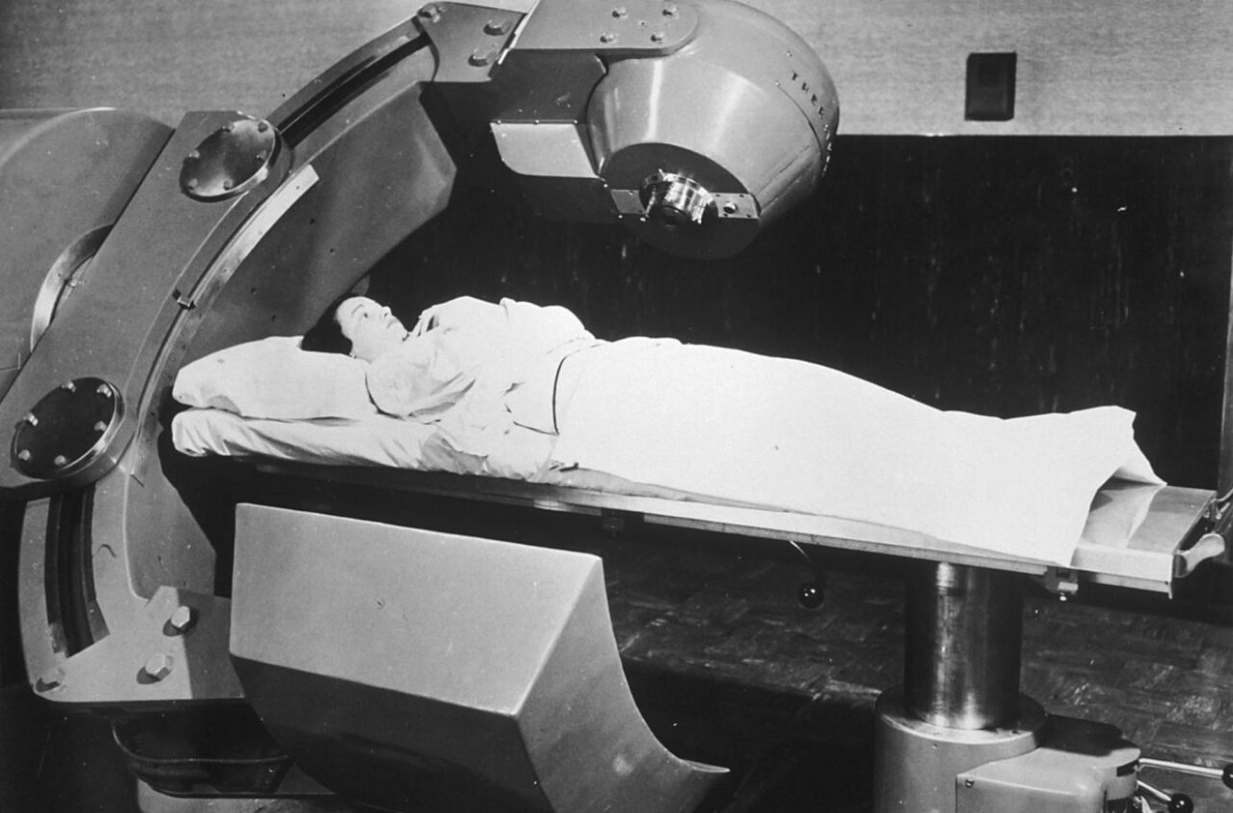

External beam radiotherapy (EBRT) is the most common form of radiotherapy (radiation therapy). The patient sits or lies on a couch and an external source of ionizing radiation is pointed at a particular part of the body. In contrast to brachytherapy (sealed source radiotherapy) and unsealed source radiotherapy, in which the radiation source is inside the body, external beam radiotherapy directs the radiation at the tumour from outside the body. Orthovoltage ("superficial") X-rays are used for treating skin cancer and superficial structures. Megavoltage X-rays are used to treat deep-seated tumours (e.g. bladder, bowel, prostate, lung, or brain), whereas megavoltage electron beams are typically used to treat superficial lesions extending to a depth of approximately 5 cm (increasing beam energy corresponds to greater penetration). X-rays and electron beams are by far the most widely used sources for external beam radiotherapy. A small number of centers operate experimental and pilot programs employing beams of heavier particles, particularly protons, owing to the rapid dropoff in absorbed dose beneath the depth of the target.

- megavoltage

- orthovoltage

- electron beams

1. X-rays and Gamma Rays

Conventionally, the energy of diagnostic and therapeutic gamma- and X-rays is expressed in kilovolts or megavolts (kV or MV), whilst the energy of therapeutic electrons is expressed in terms of megaelectronvolts (MeV). In the first case, this voltage is the maximum electric potential used by a linear accelerator to produce the photon beam. The beam is made up of a spectrum of energies: the maximum energy is approximately equal to the beam's maximum electric potential times the electron charge. Thus a 1 MV beam will produce photons of no more than about 1 MeV. The mean X-ray energy is only about 1/3 of the maximum energy. Beam quality and hardness may be improved by X-ray filters, which improves the homogeneity of the X-ray spectrum.

Medically useful X-rays are produced when electrons are accelerated to energies at which either the photoelectric effect predominates (for diagnostic use, since the photoelectric effect offers comparatively excellent contrast with effective atomic number Z) or Compton scatter and pair production predominate (at energies above approximately 200 keV for the former and 1 MeV for the latter), for therapeutic X-ray beams. Some examples of X-ray energies used in medicine are:

- Very low-energy superficial X-rays – 35 to 60 keV (mammography, which prioritizes soft-tissue contrast, uses very low-energy kV X-rays)

- Superficial radiotherapy X-rays – 60 to 150 keV

- Diagnostic X-rays – 20 to 150 keV (mammography to CT); this is the range of photon energies at which the photoelectric effect, which gives maximal soft-tissue contrast, predominates.

- Orthovoltage X-rays – 200 to 500 keV

- Supervoltage X-rays – 500 to 1000 keV

- Megavoltage X-rays – 1 to 25 MeV (in practice, nominal energies above 15 MV are unusual in clinical practice).

Megavoltage X-rays are by far most common in radiotherapy for the treatment of a wide range of cancers. Superficial and orthovoltage X-rays have application for the treatment of cancers at or close to the skin surface.[1] Typically, higher energy megavoltage X-rays are chosen when it is desirable to maximize "skin-sparing" (since the relative dose to the skin is lower for such high-energy beams).

Medically useful photon beams can also be derived from a radioactive source such as iridium-192, caesium-137 or radium-226 (which is no longer used clinically), or cobalt-60. Such photon beams, derived from radioactive decay, are more or less monochromatic and are properly termed gamma rays. The usual energy range is between 300 keV to 1.5 MeV, and is specific to the isotope. Notably, photon beams deriving from radioisotopes are approximately monoenergetic, as contrasted with the continuous bremsstrahlung spectrum from a linac.

Therapeutic radiation is mainly generated in the radiotherapy department using some of the following equipment:

- Superficial radiation therapy (SRT) machines produce low energy x-rays in the same energy range as diagnostic x-ray machines, 20 - 150 kV, to treat skin conditions.[2]

- Orthovoltage X-ray machines, which produce higher energy x-rays in the range 200–500 kV. This radiation was called "deep" because it could treat tumors at depths at which lower energy "superficial" radiation (above) was unsuitable. Orthovoltage units have essentially the same design as diagnostic X-ray machines. These machines are generally limited to less than 600 kV.

- Linear accelerators ("linacs") which produce megavoltage X-rays. The first use of a linac for medical radiotherapy was in 1953 (see also Radiation therapy). Commercially available medical linacs produce X-rays and electrons with an energy range from 4 MeV up to around 25 MeV. The X-rays themselves are produced by the rapid deceleration of electrons in a target material, typically a tungsten alloy, which produces an X-ray spectrum via bremsstrahlung radiation. The shape and intensity of the beam produced by a linac may be modified or collimated by a variety of means. Thus, conventional, conformal, intensity-modulated, tomographic, and stereotactic radiotherapy are all produced by specially-modified linear accelerators.

- Cobalt units which use radiation from the radioisotope cobalt-60 produce stable, dichromatic beams of 1.17 and 1.33 MeV, resulting in an average beam energy of 1.25 MeV. The role of the cobalt unit has largely been replaced by the linear accelerator, which can generate higher energy radiation. Cobalt treatment still has a useful role to play in certain applications (for example the Gamma Knife) and is still in widespread use worldwide, since the machinery is relatively reliable and simple to maintain compared to the modern linear accelerator.

2. Electrons

X-rays are generated by bombarding a high atomic number material with electrons. If the target is removed (and the beam current decreased) a high energy electron beam is obtained. Electron beams are useful for treating superficial lesions because the maximum of dose deposition occurs near the surface. The dose then decreases rapidly with depth, sparing underlying tissue. Electron beams usually have nominal energies in the range 4–20 MeV. Depending on the energy this translates to a treatment range of approximately 1–5 cm (in water-equivalent tissue). Energies above 18 MeV are used very rarely. Although the X-ray target is removed in electron mode, the beam must be fanned out by sets of thin scattering foils in order to achieve flat and symmetric dose profiles in the treated tissue.

Many linear accelerators can produce both electrons and x-rays.

3. Hadron Therapy

Hadron therapy involves the therapeutic use of protons, neutrons, and heavier ions (fully ionized atomic nuclei). Of these, proton therapy is by far the most common, though still quite rare compared to other forms of external beam radiotherapy, since it requires large and expensive equipment. The gantry (the part that rotates around the patient) is a multi-story structure, and a proton therapy system can cost (as of 2009) up to US$150 Million. [3]

4. Multi-leaf Collimator

Modern linear accelerators are equipped with multileaf collimators (MLCs) which can move within the radiation field as the linac gantry rotates, blocking the field as necessary according to the gantry position. This technology allows radiotherapy treatment planners great flexibility in shielding organs-at-risk (OARSs), while ensuring that the prescribed dose is delivered to the target(s). A typical multi-leaf collimator consists of two sets of 40 to 80 leaves, each around 5 mm to 10 mm thick and several centimetres in the other two dimensions. Newer MLCs now have up to 160 leaves. Each leaf in the MLC is aligned parallel to the radiation field and can be moved independently to block part of the field. This allows the dosimetrist to match the radiation field to the shape of the tumor (by adjusting the position of the leaves), thus minimizing the amount of healthy tissue being exposed to radiation. On older linacs without MLCs, this must be accomplished manually using several hand-crafted blocks.

5. Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy

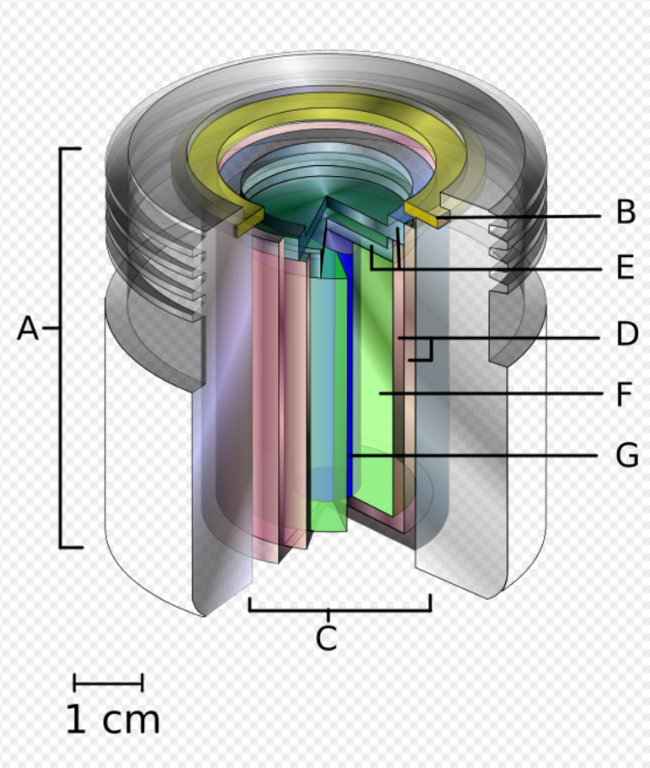

A.) an international standard source holder (usually lead),

B.) a retaining ring, and

C.) a teletherapy "source" composed of

D.) two nested stainless steel canisters welded to

E.) two stainless steel lids surrounding

F.) a protective internal shield (usually uranium metal or a tungsten alloy) and

G.) a cylinder of radioactive source material, often but not always cobalt-60. The diameter of the "source" is 30 mm. https://handwiki.org/wiki/index.php?curid=2031410

Intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is an advanced radiotherapy technique used to minimize the amount of normal tissue being irradiated in the treatment field. In some systems this intensity modulation is achieved by moving the leaves in the MLC during the course of treatment, thereby delivering a radiation field with a non-uniform (i.e. modulated) intensity. With IMRT, radiation oncologists are able to break up the radiation beam into many "beamlets". This allows radiation oncologists to vary the intensity of each beamlet. With IMRT, doctors are often able to further limit the amount of radiation received by healthy tissue near the tumor. Doctors have found this sometimes allowed them to safely give a higher dose of radiation to the tumor, potentially increasing the chance of a cure.[4]

5.1. Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy

Volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) is an extension of IMRT where in addition to MLC motion, the linear accelerator will move around the patient during treatment. This means that rather than radiation entering the patient through only a small number of fixed angles, it can enter through many angles. This can be beneficial for some treatment sites where the target volume is surrounded by a number of organs which must be spared radiation dose.[5]

5.2. Flattening Filter Free

The intensity of the X-rays produced in an megavoltage linac is much higher in the centre of the beam compared to the edge. To counteract this a flattening filter is used. A flattening filter is a cone of metal (typically tungsten); after the X-ray beam has passed through the flattening filter it will have a more uniform profile, since the flattening filter is shaped so as to compensate for the forward bias in the momentum of the electrons incident upon it. This makes treatment planning simpler but also reduces the intensity of the beam significantly. With greater computing power and more efficient treatment planning algorithms, the need for simpler treatment planning techniques ("forward planning", in which the planner directly instructs the linac on how to deliver the prescribed treatment) is reduced. This has led to increased interest in flattening filter free treatments (FFF).

The advantage of FFF treatments is the increased maximum dose rate, by a factor of up for four, allowing reduced treatment times and a reduction in the effect of patient motion on the delivery of the treatment. This makes FFF an area of particular interest in stereotactic treatments.[6] , where the reduced treatment time may reduce patient movement, and breast treatments[7], where there is the potential to reduce breathing motion.

6. Image-guided Radiation Therapy

Image-guided radiation therapy (IGRT) augments radiotherapy with imaging to increase the accuracy and precision of target localization, thereby reducing the amount of healthy tissue in the treatment field. The more advanced the treatment techniques become in terms of dose deposition accuracy, the higher become the requirements for IGRT. In order to allow patients to benefit from sophisticated treatment techniques as IMRT or hadron therapy, patient alignment accuracies of 0.5 mm and less become desirable. Therefore, new methods like stereoscopic digital kilovoltage imaging based patient position verification (PPVS)[8] to alignment estimation based on in-situ cone-beam computed tomography (CT) enrich the range of modern IGRT approaches.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Medicine:External_beam_radiotherapy

References

- Advances in kilovoltage x-ray beam dosimetry in http://iopscience.iop.org/0031-9155/59/6/R183/article

- House, Douglas W. (18 March 2016). "Sensus Healthcare on deck for IPO". Seeking Alpha. http://seekingalpha.com/news/3168459-sensus-healthcare-deck-ipo.

- https://www.forbes.com/forbes/2009/0316/062_150mil_zapper.html#5e82200f2068

- "External Beam Radiation Therapy". Archived from the original on 2010-02-28. https://web.archive.org/web/20100228043635/http://www.rtanswers.com/treatmentinformation/treatmenttypes/externalbeamradiation.aspx.

- "IMRT and VMAT" (in en). http://www.christie.nhs.uk/patients-and-visitors/your-treatment-and-care/treatments/radiotherapy/what-we-do/imrt-and-vmat/.

- Georg, Dietmar; Knöös, Tommy; McClean, Brendan (2011). "Current status and future perspective of flattening filter free photon beams". Medical Physics 38 (3): 1280–1293. doi:10.1118/1.3554643. PMID 21520840. https://dx.doi.org/10.1118%2F1.3554643

- Koivumäki, Tuomas; Heikkilä, Janne; Väänänen, Anssi; Koskela, Kristiina; Sillanmäki, Saara; Seppälä, Jan (2016). "Flattening filter free technique in breath-hold treatments of left-sided breast cancer: The effect on beam-on time and dose distributions". Radiotherapy and Oncology 118 (1): 194–198. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.032. PMID 26709069. http://www.thegreenjournal.com/article/S0167-8140(15)00652-0/fulltext.

- Boris Peter Selby, Georgios Sakas et al. (2007) 3D Alignment Correction for Proton Beam Treatment. In: Proceedings of Conf. of the German Society for Biomedical Engineering (DGBMT). Aachen.