1. Introduction

The growing prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia, with 100 million cases estimated by 2050, is becoming a serious public health concern with both individual and socioeconomic burdens [

1]. Although the rise in life expectancy is one of the main causes of the increased prevalence, multiple other factors are likely to play a role. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to the impact of diet on brain health and mental function [

2,

3], with several dietary components, such as carbohydrates, fats, and hormones, reported to influence cognition [

1]. Indeed, the consumption frequency of healthy or unhealthy foods perfectly correlates with better or worse cognitive performance in older adults [

4]. It would seem, therefore, that our diet directly affects brain health and the probability of developing dementia and neurodegenerative disorders in later life.

The consumption of high-fat/high-sugar diets in modern civilizations, combined with overeating behaviors and sedentary lifestyles, has led to exponential growth in obesity cases worldwide, reported to be 650 million people in 2016, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [

5]. Obesity increases the risk of developing dementia in later life [

6,

7], and has been associated with immediately altered cognitive performance, including impaired verbal learning, working memory, stimulus reward learning, and executive functions (adaptation to novel situations, cognitive flexibility, attention span, planning, and judgment) [

8,

9,

10]. Obesity is also considered a risk factor for developing multiple comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes (T2D), hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome (MetS), all of which may have an independent impact on cognition. In fact, T2D (with 422 million cases in 2014, according to the WHO, [

11]) correlates with cognitive dysfunction, including reduced information processing speed and altered verbal, visual memory, and executive functions [

12,

13,

14]. Even impaired glucose tolerance, which develops prior to T2D, is considered a risk factor for cognitive damage [

15]. In addition, also associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment and dementia is MetS [

16,

17,

18], defined as a multifactorial disorder characterized by abdominal obesity, insulin resistance, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia [

19]. However, still poorly understood are the physiopathological mechanisms by which metabolic diseases affect learning and memory processes, and raise the risk of late-life dementia and neurodegeneration.

During learning and memory task performance, neural networks, in a process called neuroplasticity [

20], make new connections and/or adjustments in synaptic strength, especially in the hippocampal glutamatergic circuits. This reorganization is carried out by tight control of the number of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate ionotropic receptors (AMPARs) in the post-synaptic zone (PSZ). Since glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, AMPARs are the main mediators of fast synaptic transmission. Functional receptors are tetrameric assemblies of subunits GluA1-4. Whereas GluA4 is mostly expressed during early development stages, in mature excitatory neurons, AMPARs contain two dimers of GluA1/GluA2 (~80% of all synaptic AMPARs) or GluA2/GluA3 heteromers [

21]. In resting conditions, the presence of GluA2 in surface AMPARs makes these Ca

2+-impermeable [

20]. Following stimulation with glutamate, precise regulation leads to synaptic incorporation of GluA1-GluA1 homomers. These GluA2-lacking AMPARs are Ca

2+-permeable (CP-AMPARs), and, over a restricted period of time, induce Ca

2+-sensitive signaling events that sustain synaptic potentiation or modulate subsequent neuroplasticity. However, aberrant incorporation of CP-AMPARs can result in excessive Ca

2+ influx, inducing excitotoxicity and cell death, as reported for brain diseases [

22]. An excitotoxic influx of Ca

2+ is also mediated by overactivation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate ionotropic receptors (NMDARs) [

23]. Functional NMDARs are tetramers of GluN1 (A or B) and GluN2 (A-D), and are also involved in neuroplasticity modulating synaptic incorporation of CP-AMPARs.

Changes in the expression of a particular subunit of AMPARs produce an imbalance in AMPAR tetrameric composition or dysregulate its trafficking toward the PSZ, and both have been linked to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and cognitive aging [

21,

24]. In AD, high levels of amyloid-β oligomers (Aβ)—a main pathological hallmark, together with Tau phosphorylation—induce readjustments in the synaptic insertion of CP-AMPARs [

25,

26]. Soluble Aβ oligomers reduced surface expression of AMPARs and blocked their extrasynaptic delivery mediated by chemical synaptic potentiation in neuronal cultures [

26]. However, intracellular infusion of oligomeric Aβ enhanced AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission in hippocampal slices, but the knockdown of GluA1 prevented this effect, suggesting that intracellular Aβ induced synaptic insertion of CP-AMPARs [

25]. In any case, Aβ dysregulates AMPAR trafficking [

27] and AMPAR-mediated synaptic plasticity impairment is one of the early onsets of AD (reviewed by [

21]). This early synaptic dysfunction largely precedes any sign of cognitive decline, in both neurodegenerated and aged brains [

21,

28]. The fact that impaired learning and memory processes in AD and aged people are exacerbated by unhealthy diets [

29], underlines the impact of nutritional factors at the synaptic level. Additionally, dynamic regulation of AMPARs has been associated with different metabolic situations, orexigenic and anorexigenic hormones (like leptin and ghrelin), and dietary factors [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

In summary, it is becoming evident that dietary habits and specific nutrients play an essential role in brain health. However, solid evidence of nutritional control of synaptic function focused on AMPARs and its correlation with cognitive performance is not completely understood.

2. Western Diet

In recent decades, most societies have gradually abandoned dietary traditions to globalize their lifestyles. In southern Europe, for instance, the Western diet (WD), featured by high animal-based food, fat, and simple sugar intake, is gradually replacing the primarily plant-based Mediterranean diet (MedDiet), rich in vegetables, fruit, whole grains, olive oil, and fish, and low in red meats and refined sugars [

35], and associated with a lower rate of cognitive function decline [

36].

It has been documented that diets high in either fats or simple sugars have deleterious effects on cognition (discussed below), so the combination of both in the WD evidently contributes to memory and learning impairments. In lean young humans, a 4- or 8-day intervention with a Western style-based breakfast (high in saturated fats and added sugars) was enough to reduce hippocampal-dependent learning and memory [

37,

38]. In a longitudinal study of elderly people, the WD was a predictor of poorer memory and processing speed [

39]. There is, however, little literature analyzing the effects of the WD and its components on brain function in humans [

40], which is why we revisit experimental approaches with animal models.

2.1. Cognition Studies in Animal Models

While several high-fat diet (HFD)/high-sugar diet (HSD) protocols in animal models aim to mimic the WD in humans, many factors determine cognitive outcomes, such as the nature and percentages of fats and sugars (in WD-mimetics approaches, and in healthier control diets typically composed of 45–65% carbohydrates and 5–15% fats), palatability, exposure over time, individual susceptibility or resistance to obesity, and cognition tests used to measure learning and memory. With just a few exceptions, in which no differences were reported at 5, 10, or 12 weeks of the WD [

41,

42,

43], a wide range of experimental models have demonstrated negative WD effects on learning and on short- and long-term memory, the details of which are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1. WD effects on synaptic function and cognition in animals.

| Exp. Approach |

Species, Sex, Age |

Model |

Learning/Memory |

Synaptic Function, Neuroplasticity |

Other Pathways |

Refs. |

| Short periods (≤2 months) |

| Young animals |

Rat (♀; 3 w) |

CAFD (F/sucrose: 45%) & HFru solution (11%) or HFru solution alone vs. CD (F: 13.4% & C: 56.7%) for 5 w. Reversion: 5 w with CD |

Impaired memory (novel object in context) at 5 w for CAFD and HFru solution. No reversion in CAFD group |

- |

Gut dysbiosis (before and after reversion) |

[44] |

| |

Rat (♂; 6 w) |

HFD-HDextrose (F: 41.7% & C: 36.7%) vs. CD (F: 13.5% & C: 58%) for 11 w |

Impaired memory (NOR; no changes with MWM) |

↓ dendritic arborization in HPC neurons and ↑ in entorhinal cortex neurons |

↑ TNFα levels in blood |

[45] |

| |

Rat (♂; 6 w) |

CAFD (cakes, biscuits & a protein source) & HSu solution (10%) vs. CD for 6 w |

Impaired memory (NOR and NLR) |

No changes in BDNF, TrkB and synapsin in HPC |

↑ inflammation and gut dysbiosis |

[46] |

| |

Rat (♀; 2 m) |

HFD (F:39%) & refined sugar (40%) vs. CD (F: 13% & complex C: 59%) for 2 m |

Impaired memory (MWM) |

↓ BDNF, phosphosynapsin I and phosphoCREB |

- |

[47] |

| Adult animals |

Rat (♂ and ♀; 9–10 w) |

HFD (F: 60% & C: 20%) HFru solution (11%) vs. CD (F: 13% & C: 62%) for 6 w |

Impaired hippocampal-dependent memory (NLR) in ♂ (no changes in ♀) |

- |

- |

[48] |

| |

Rat (♂; adult) |

CAFD (F: 45% & C: 50%) & HSu solution (10%) vs. CD (F: 15%, & C: 59%) for 5, 11 & 20 days |

Impaired hippocampal-dependent memory (NLR; no changes in NOR) |

No changes in BDNF |

↑ inflammation in HPC at 20 d |

[49] |

| |

Rat (♂) |

CAFD (CD supplemented with cakes, biscuits & protein source) & HSu solution (10%) vs. CD for 5 w |

Impaired memory (NLR) |

- |

Gut dysbiosis |

[50] |

| |

Rat (♂; adult) |

HFD-HC (F: 25%, C: 44% & P: 18%) vs. CD (F: 5%, C: 62% & P: 18) for 6 w |

Impaired short-term and long-term memory (RAWM) |

No changes in BDNF |

↑ oxidative stress in HPC |

[51] |

| |

Rat (♂) |

HFD (F: 40%, P: 5% & C: 15%) & HSu solution (40%) vs. CD (F: 15%, P: 25% & C: 55%) for 6 w. Reversion: 3 w with HFD-HSu and 3 w with CD and training |

Impaired memory (NLR). Reversed by CD and training |

- |

- |

[52] |

| |

Rat (♂) |

HFD (SFAs & MUFAs; 38%) & refined sugar (38%) vs. CD (F: 6% & sugar: 4.1%) for 8 w |

Impaired memory (NOR) and learning (MWM) |

↓ GluA3 levels in dorsal HPC and altered levels in synaptic plasticity markers |

Altered levels in energy metabolism markers (by proteomic analysis) |

[53] |

| Long periods (>2 months) |

| Young animals |

Rat (♂; 21 days) |

HFD (F: 29%, sucrose: 34% & cholesterol 1.25%) & HGlucose-HFru solution (55%/45%) vs. CD (F: 6% & C: 44%) for 8 m |

- |

↓ PSD95 and BDNF, ↓ LTP in HPC |

Gut dysbiosis, ↑ inflammation and microglia activation in HPC |

[54] |

| |

Rat (♀; 1 m) |

HFD (30% lard & 66% sucrose) & HSu solution (30%) vs. CD (F: 3%, C: 61% & P: 19%) for 24 m |

Impaired memory (NOR) |

↓ TrKB, ↓ LTP in HPC |

No changes in neurogenesis |

[55] |

| |

Rat (♂; 5–7 w) |

HFD & HSu solution (5%) vs. CD for 4 m. Reversion: 3 m with bioactive food |

Impaired spatial and working memory (T-maze and NOR). Reversed by bioactive foods |

- |

Gut dysbiosis. Reversed by bioactive foods |

[56] |

| |

Rat (♂; 6 w) |

HFD-HFru (F: 30% & fructose: 15%) vs. CD for 6 m |

Impaired learning (MWM) |

- |

↑ BBB permeability, neurodegeneration and microglia activation |

[57] |

| |

Rat (♂; 6 w) |

HFD-HFru (saturated F: 45% & fructose: 20%) vs. CD for 11 w |

Impaired memory (NOR) |

- |

↓ IGF1 and ↑ oxidative stress |

[58] |

| |

Mouse (♂; 6 w) |

HFD-HSu (F: 60% & sucrose: 7%) vs. CD (F: 17%) for 13 w |

Impaired memory (NOR) |

↓ GluA1, BDNF, phosphoCREB, TrkB in HPC and PFC |

↓ neurogenesis |

[59] |

| |

Mouse (♂; 7 w) |

HFD (F: 40% & C: 20%) & HSu solution vs. CD (F: 12% & C: 67%) for 14 w |

- |

↓ PSD95 and ↑ phosphoTau in brain (no changes in synaptophysin) |

↓ GLUT1/3, ↑ ER stress and inflammation responses and INS resistance in brain |

[60] |

| |

Rat (♂; 7 w) |

CAFD (CD with cookies, cakes & biscuits) vs. CD once per day, 5 days per week for 5 m |

- |

↑ BDNF and TrkB and ↓ phosphoTrkB in PFC. No changes in HPC |

Redox imbalance |

[61] |

| |

Rat (♀; 8–10 w) |

HFD (F: 40%, C: 45% & P 15%) & HFru solution (15%) vs. CD (F: 6%, C: 64% & P: 25%) for 12, 16 & 24 w |

Impaired memory (MWM) at 16 and 24 w (no changes at 12 w) |

- |

↑ oxidative stress and reduced antioxidant levels in HPC and CTX |

[43] |

| |

Rat (♂; 2 m) |

HFD-HGlucose (F: 40%) vs. CD (F: 13%) for 3 m |

Impaired learning (nonspatial discrimination learning problem) |

- |

↑ BBB permeability in HPC |

[62] |

| |

Rat (♀; 2 m) |

HFD (SFAs & MUFAs: 39%) & refined sugar (40%) vs. CD (F: 13% & C: 59%) for 1, 2 & 6 m or 2 y |

Impaired learning and memory (MWM) at 1 and 2 m |

↓ BDNF and synapsin I in HPC |

- |

[63] |

| |

Rat (♂; 2 m) |

HFD (high-lard or high-olive oil) & HSu solution vs. CD for 10 w |

No changes in spatial memory (Y-maze) |

↓ GluN2A in high-lard-HSu (no changes in high-olive oil-HSu) in CTX |

- |

[42] |

| |

Rat (♂; 2 m) |

HFD-HSu & HFru corn syrup solution (20%) vs. CD for 8 m |

Impaired learning (MWM) |

↓ dendritic spine density, ↓ LTP and ↓ BDNF levels in CA1-HPC |

- |

[64] |

| |

Mouse (♀ and ♂; 10 w) |

HFD (F: 60%) & HSu solution (20%) vs. CD (F: 10%) for 4 or 6 m. Reversion: 8 w with CD |

Impaired memory (NOR and NLR. No change in working memory (Y-maze). Recovered after 8 w of CD |

|

↑ microglia activation (no inflammation and neuronal loss). Recovered after 8 w of CD |

[65] |

| |

Guinea pigs (♀; 10 w) |

HFD-HSu (F: 20% & sucrose: 15%) vs. CD (F: 4% & sucrose: 0%) for 7 m |

- |

↓ BDNF levels in HPC |

- |

[66] |

| |

Rat (♂; adolescent) |

HFD-HDextrose (SFAs: 41.7%) vs. CD (F: 13.4%) for 10 w |

Impaired memory (NOR) |

- |

- |

[67] |

| Adult animals |

Mouse (♂; 3 m) |

HFD (F: 45%) & HFru solution (10%) vs. CD for 10 w |

Impaired memory (MWM) |

↓ PSD95 and SNAP25 in HPC |

INS resistance, ↑ microglia activation and inflammation in brain |

[68] |

| |

Rat (♂) |

HFD-HDextrose (F: 38%, P: 24%, C: 18% & dextrose: 20%) vs. CD (F: 18%, P: 24%, C: 58%) for 10, 40 & 90 days |

Impaired learning at 10 and 90 d, no changes at 40 d (Y-shaped maze) |

- |

↑ BBB permeability in HPC (only in obese rats) |

[41] |

| |

Mouse (♂; 3 m) |

HFD-HFru (F: 48%, fructose: 33% & P: 19%) or HFD (F: 48%, C: 33% & P: 19%) vs. CD for 14 w |

Impaired memory (NOR and NLR). HF-HFru more affected than HFD |

↓ glutamate and glutamine in HPC (no changes in GABA) |

- |

[69] |

| |

Rat (♂) |

HFD-HDextrose (F: 40%, P: 21% & C: 38%) or HFD-HSu (F: 40%, P: 21% & C: 38%) vs. CD (F: 12%, P: 28% & C: 59%) for 3 m |

Impaired learning (nonspatial Pavlovian discrimination and reversal learning problem) |

↓ BDNF in prefrontal CTX and HPC with HF-HDextrose (no changes with HF-HSu) |

- |

[70] |

| |

Rat (♂ and ♀) |

HFD-HFru (CD: 60%, fructose: 30% & pork fat: 10%) vs. CD for 12 w |

Impaired learning (MWM and passive avoidance test). ♂ more affected than ♀ |

- |

↑ oxidative stress |

[71] |

| Short vs. long periods |

| Young animals |

Mouse (♂; 6 w) |

HFD-HFru (30% lard, 0.5% cholesterol and 15% fructose, all in weight/weight) vs. CD for 4 or 24 w |

Impaired learning (MWM) at 14 w (no changes at 4 w) |

- |

↑ BBB permeability and astrocytocis |

[72] |

As happens in humans, short exposition to Western style-based breakfast was enough to reduce memory in rodents. Five days of exposure to a non-standardized cafeteria diet (CAFD) composed of cakes, biscuits, and a protein source, plus a high-sucrose (HSu) solution, compromised hippocampal-dependent place recognition memory in adult rats, although other memory tasks remained unaffected [

49]; comparable deficits were also reported for the CAFD without the HSu solution and the HSu solution without the CAFD. In young rat females, 5 weeks of CAFD or high-fructose solution (HFru) intake induced similar memory impairments, and intervention with a healthier diet was only able to revert HFru-mediated, but not CAFD-mediated deficits [

44]. In adult mouse males, 14 weeks of combined HFD and HFru (HFD-HFru) intake resulted in a poorer cognitive performance than with an HFD alone [

69]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies proving whether longer-term consumption of an HFD or HSD have additive effects in memory loss and synaptic function. However, we believe that this is likely the case, since high intake of both would simultaneously damage different signaling pathways with the same result.

Especially relevant is the fact that this brain damage is not equal in both sexes. In adult animals, females seem to be more resistant to WD-induced cognitive impairment than males [

48,

71]. Males are reported to consume a high percentage of calories from fats and proteins, while females show a greater preference for sweet-related calories [

48]. However, sexual dysmorphism in nutrient choice is not the only reason to explain sex-specific consequences of the WD on cognitive outcomes, as sex hormones play an important role. In male rats, gonadectomy reverted HFD-HFru effects on some learning and memory tasks, but did not improve or even worsen the effects in females [

71]. In non-human primates on an obesogenic diet, estrogen replacement therapy after an ovo-hysterectomy increased cognitive performance [

73]. More in-depth studies analyzing sex- and hormone-dependent effects of an HFD or HSD on synaptic and cognitive injury could lead to better diet interventions for patients with MetS, especially for women after the menopause.

There is hope in the fact that WD-induced impairment in memory seems to be reversible, as demonstrated for male and female young animals switched from 4 months on an HFD/HSD to a more balanced control diet for 6 weeks [

52,

65], and also for male adult animals on a 3-week WD followed by a 3-week control diet [

62]. By contrast, AD-related pathology would be exacerbated by the WD, which has been shown to accelerate age-associated cognitive decline in AD animal models (as demonstrated, for example, in [

74,

75]).

Moreover, the cognitive dysfunction associated to MetS can be countered by life-style strategies in clinical and preclinical studies, including healthy dietary habits, some dietary supplements (like vitamins and antioxidants), reduced calorie intake, and exercise [

76,

77], whereas no medications successfully treat cognitive impairment in these patients. Neither antihypertensive, statins nor drugs for AD have revealed efficiency on slowing cognitive deficits in preclinical models of MetS [

78,

79]. By contrast, high adherence to the MedDiet decreased the risk of developing cognitive impairment and dementia even in individuals with established MetS [

77,

80]. Accordingly, meals with a high content in fruits and vegetables, or in fish, exhibit a significant inverse association with cognitive decline in the general population and have a preventive role in cognition-related alteration associated with MetS [

81,

82]. In summary, healthy nutritional habits and lifestyle interventions are nowadays the best therapeutic strategy to reduce MetS components and prevent or delay cognitive decline.

2.2. Synaptic Function and Neuroplasticity

WD-compromised acquisition of new information in learning and memory processes perfectly correlates with deficits in hippocampal dendrites, synapsis morphology, and activity-dependent functional plasticity, as exemplified by the long-term potentiation (LTP) paradigm. LTP is an electrophysiologic high-frequency stimulation protocol that mimics physiologic activity during learning and memory [

20]. This stimulation increases the number of CP-AMPARs (GluA1-GluA1 tetramers) in the PSZ, inducing trafficking to the cell surface via the recycling pathway and lateral movement from perisynaptic sites, and enhancing synaptic transmission efficiency. It has been reported that long-term WD-impaired synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (HPC) reduces dendritic spine density and LTP [

54,

55,

64], and also that the WD alters dendritic arborization, which is reduced in the HPC and increased in the entorhinal cortex [

45]. This last finding could be a compensatory effect due to synaptic loss in distal regions like the HPC or even in proximal synapses, since the WD has also been reported to impair episodic memory in this particular case.

WD-mediated cognitive impairment is associated with deficits in certain synaptic proteins. Levels of the main neurotrophin, i.e., brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), were reduced in the HPC of adult mice after long-term exposure (2–8 months) to the WD [

47,

54,

63,

64,

66,

70], while no differences were observed for shorter exposure (20–42 days) [

46,

49,

51]. A decrease in the BDNF receptor, tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), has also been reported [

55,

59]. Interestingly, not all nutritional sources alter BDNF levels in the same way. While a high-dextrose HFD downregulated BDNF in both the HPC and prefrontal cortex (PFC), this was not the case for a high-sucrose HFD [

70].

Moreover, proteomic analysis of the dorsal HPC of rats on the WD for 8 weeks revealed alterations in synaptic plasticity markers, including a specific reduction in AMPAR subunit GluA3 [

53]. In fact, selectively decreased synaptic GluA3 has also been shown to be involved in dendritic spine loss in frontotemporal dementia [

83]. Other long-term WD paradigms demonstrate reductions in other glutamate receptors, including the AMPAR subunit GluA1 (at 13 weeks) [

59] and the NMDAR subunit GluN2A (at 10 weeks) [

42]. The decrease in GluA1 may occur because BDNF regulates its synthesis [

84]. At synaptic sites, GluN2A-lacking NMDARs may display altered synaptic plasticity, as described for its deletion in pyramidal cells from HPC slices [

85]. Lower levels of glutamate and its precursor, glutamine, have also been detected in the HPC of HFD-HFru- and HFD-fed mice, while gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the most common inhibitory neurotransmitter, remained unaltered [

69]. Short-term studies are needed, nonetheless, to understand whether the deleterious effects of the WD on memory loss are a cause or consequence of changes in the glutamate neurotransmitter and its receptors.

2.3. Other Mechanisms

Other mechanisms are also compromised in WD-induced cognitive damage: insulin (INS) signaling in the brain [

60,

68], blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability [

41,

57,

62], HPC inflammation [

45,

46,

49,

54,

60,

68], microglia activation [

54,

57,

65,

68,

72], endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and oxidative stress [

43,

51,

58,

60,

61,

71], gut microbiome composition [

44,

46,

54,

56,

58], and neurogenesis [

59]. Therapeutic strategies based on modulating these mechanisms have demonstrated unequal effects on memory loss.

Insulin supplementation has been shown to prevent WD-reduced neuroplasticity [

54], and treatment with metformin, the first line drug for T2D, improved cognitive function in HFD-HFru-fed mice, but failed to restore BBB permeability [

57]. It remains unclear whether the loss of BBB permeability mediated by the WD is a cause of memory loss. It has been reported that an HFD-HFru produced BBB dysfunction after 4 weeks, but no significant decline in learning and memory [

72]. In contrast, other studies, using different HFD/HSD paradigms, showed cognitive impairment after shorter exposure to the WD [

41,

49,

63], in one case, reporting increased BBB permeability in WD-induced obese subjects at 12 weeks, but not in WD-resistant obese subjects at 5 weeks [

41]; this would suggest that BBB leakage could, depending on exposure time, diet composition, and obesity phenotype, be a consequence of the WD.

Furthermore, pre-exposure to a probiotic called VSL#3 prevented WD-induced memory deficits for an HPC-dependent task, but caused deficits for a perirhinal-dependent task, irrespective of diet and dose [

50], suggesting that this probiotic may be detrimental for healthy subjects. In one study, treatment with the antibiotic minocycline, which alters microbiome composition, prevented or reverted CAFD-induced spatial memory impairment [

46]; however, another study showed that dietary intervention restored CAFD-dependent memory loss, but not gut microbiota alterations [

44]. Finally, vitamin E administration normalized the effect of the CAFD on HPC oxidative stress markers and prevented diet-mediated memory decline [

51]. The above are just some examples of efforts focused on discovering new drugs and/or bioactive foods with neuroprotective properties that could counteract HFD/HSD-induced brain damage.

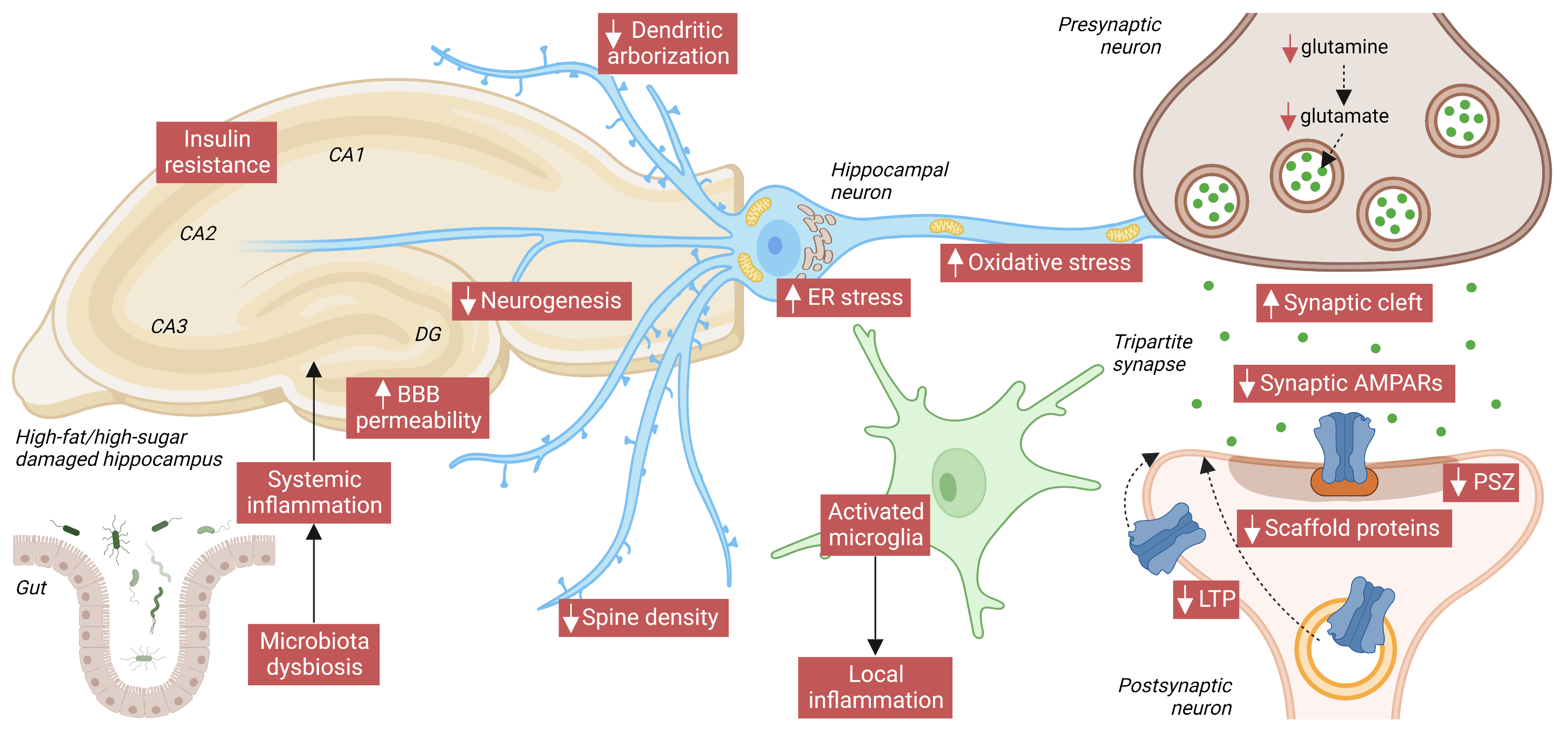

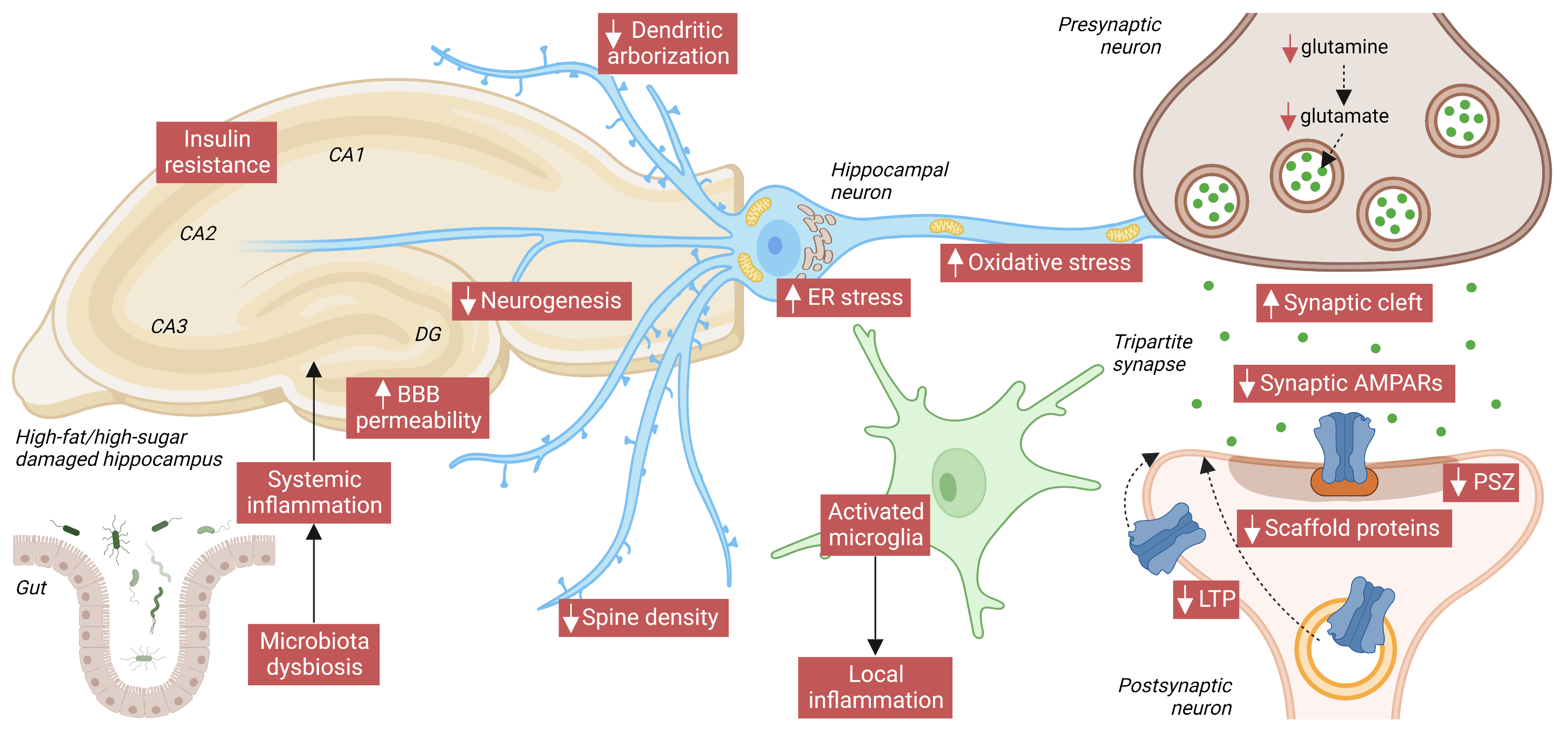

In conclusion, an association between WD and alterations in memory and learning processes has been demonstrated both in human studies and experimental approaches on animal models. Such effects correlated with synaptic and neuroplasticity dysfunctions in the hippocampus, corresponding with reduced dendritic spine density and arborization, decreased LTP, and deficits in synaptic proteins, like AMPARs (as summarized in the following figure). Furthermore, other mechanisms regarding INS signaling and BBB permeability, among others, appeared to be affected too. Fortunately, WD-induced cognitive decline seems to be reversible, as shown in animal studies that switched from an HFD/HSD to a more balanced control diet. However, more in-depth investigations are required to fully understand the effect of WD and its components on brain function to create better diet interventions to ameliorate cognitive alterations.

Figure. Main hallmarks of HFD/high-sugar-(HSD)-mediated HPC damage. At the systemic level, both fat and sugar produce gut microbiota dysbiosis, which can exacerbate inflammation in the brain by enhancing blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. BBB damage, in turn, contributes to deregulating transport of circulating orexigenic and anorexigenic hormones. In the HPC, local release of neuroinflammatory factors by activated microglia exacerbates neuronal damage. INS resistance, increased endoplasmic reticulum (ER), and oxidative stress also compromise neuronal function. In HPC neurons, HFD/HSD intake reduces dendritic arborization, spine density, and the PSZ, and widens the synaptic cleft. The glutamate neurotransmitter and its precursor, glutamine, are reduced, and also reduced over the short/medium-term are levels of AMPARs and of its scaffold protein PSD95. Finally, impaired activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (especially LTP) proves that AMPAR trafficking to the PM is also compromised by an HFD/HSD. Image created with Biorender.com

Interestingly, more knowledge about the effects of nutrients at cognitive, synaptic and neuroplasticity level can be achieved reviewing current evidence with HFD alone (especially considering the fat type) and HSD alone (comparing fructose and sucrose intake), as documented in the following chapters.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu14194137