The Peshitta (Classical Syriac: ܦܫܝܛܬܐ pšîṭtâ) is the standard version of the Bible for churches in the Syriac tradition. The consensus within biblical scholarship, though not universal, is that the Old Testament of the Peshitta was translated into Syriac from Hebrew, probably in the 2nd century AD, and that the New Testament of the Peshitta was translated from the Greek. This New Testament, originally excluding certain disputed books (2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, Revelation), had become a standard by the early 5th century. The five excluded books were added in the Harklean Version (616 AD) of Thomas of Harqel. However, the 1905 United Bible Society Peshitta used new editions prepared by the Irish Syriacist John Gwynn for the missing books.

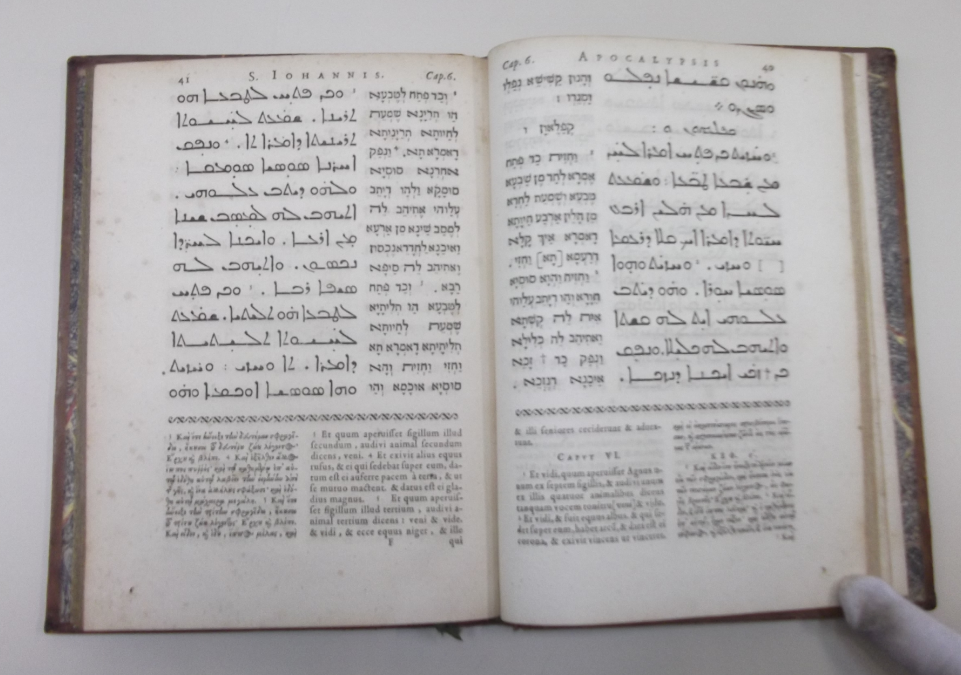

- harqel

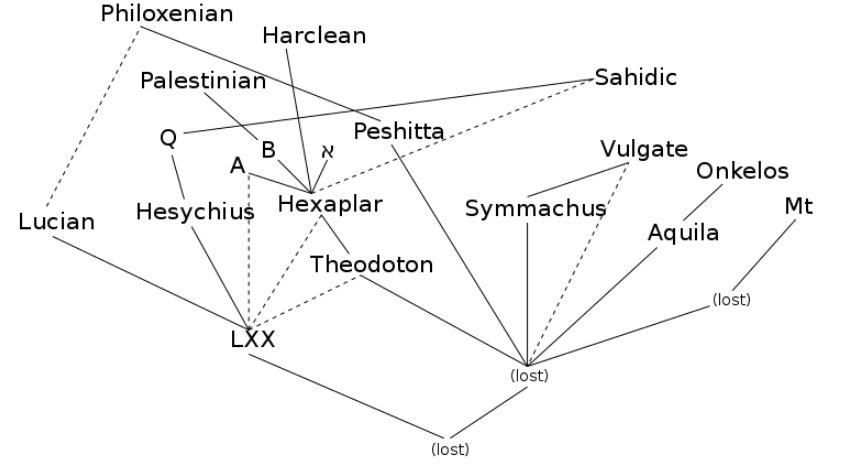

- peshitta

- syriac

1. Etymology

The name 'Peshitta' is derived from the Syriac mappaqtâ pšîṭtâ (ܡܦܩܬܐ ܦܫܝܛܬܐ), literally meaning 'simple version'. However, it is also possible to translate pšîṭtâ as 'common' (that is, for all people), or 'straight', as well as the usual translation as 'simple'. Syriac is a dialect, or group of dialects, of Eastern Aramaic, originating around Edessa. It is written in the Syriac alphabet, and is transliterated into the Latin script in a number of ways, generating different spellings of the name: Peshitta, Peshittâ, Pshitta, Pšittâ, Pshitto, Fshitto. All of these are acceptable, but 'Peshitta' is the most conventional spelling in English.

2. History of the Syriac Versions

2.1. Analogy of Latin Vulgate

There is no full and clear knowledge of the circumstances under which the Peshitta was produced and came into circulation. Whereas the authorship of the Latin Vulgate has never been in dispute, almost every assertion regarding the authorship of the Peshitta and its time and place of its origin, is subject to question. The chief ground of analogy between the Vulgate and the Peshitta is that both came into existence as the result of a revision. This, indeed, has been strenuously denied, but since Hort maintained this view in his Introduction to New Testament in the Original Greek, following Griesbach and Hug at the beginning of the 19th century, it has gained many adherents. As far as the New Testament writings are concerned, there is evidence, aided and increased by recent discoveries, for the view that the Peshitta represents a revision, and fresh investigation in the field of Syriac scholarship has raised it to a high degree of probability. The very designation, "Peshito," has given rise to dispute. It has been applied to the Syriac as the version in common use, and regarded as equivalent to the Greek "koiné"(κοινἠ) and the Latin "Vulgate" (Vulgata).[1]

2.2. The Designation "Pshitto" ("Peshitta")

The word itself is a feminine form, meaning "simple", as in "easy to be understood". It seems to have been used to distinguish the version from others which are encumbered with marks and signs in the nature of a critical apparatus. However, the term as a designation of the version has not been found in any Syriac author earlier than the 9th or 10th century.

As regards the Old Testament, the antiquity of the version is admitted on all hands. The tradition, however, that part of it was translated from Hebrew into Syriac for the benefit of Hiram in the days of Solomon is surely a myth. That a translation was made by a priest named Assa, or Ezra, whom the king of Assyria sent to Samaria, to instruct the Assyrian colonists mentioned in 2 Kings 17:27-28, is equally legendary. That the translation of the Old Testament and New Testament was made in connection with the visit of Thaddaeus to Abgar at Edessa belongs also to unreliable tradition. Mark has even been credited in ancient Syriac tradition with translating his own gospel (written in Latin, according to this account) and the other books of the New Testament into Syriac.[1]

3. Syriac Old Testament

What Theodore of Mopsuestia says of the Old Testament is true of both: "These Scriptures were translated into the tongue of the Syriacs by someone indeed at some time, but who on earth this was has not been made known down to our day".[2] F. Crawford Burkitt concluded that the translation of the Old Testament was probably the work of Jews, of whom there was a colony in Edessa about the commencement of the Christian era.[3] The older view was that the translators were Christians, and that the work was done late in the 1st century or early in the 2nd. The Old Testament known to the early Syrian church was substantially that of the Palestinian Jews. It contained the same number of books, but it arranged them in a different order. First, there was the Pentateuch, then Job, Joshua, Judges, 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, 1 and 2 Chronicles, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Ruth, the Song of Songs, Esther, Ezra, Nehemiah, Isaiah followed by the Twelve Minor Prophets, Jeremiah and Lamentations, Ezekiel, and Daniel. Most of the Deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament are found in the Syriac, and the Wisdom of Sirach is held to have been translated from the Hebrew and not from the Septuagint.[1]

4. Syriac New Testament

Of the New Testament, attempts at translation must have been made very early, and among the ancient versions of New Testament scripture, the Syriac in all likelihood is the earliest. It was at Antioch, the capital of Syria, that the disciples of Christ were first called Christians, and it seemed natural that the first translation of the Christian Scriptures should have been made there. The tendency of recent research, however, goes to show that Edessa, the literary capital, was more likely the place.

If we could accept the somewhat obscure statement of Eusebius[4] that Hegesippus "made some quotations from the Gospel according to the Hebrews and from the Syriac Gospel," we should have a reference to a Syriac New Testament as early as 160–180 AD, the time of that Hebrew Christian writer. One thing is certain, the earliest New Testament of the Syriac church lacked not only the Antilegomena – 2 Peter, 2 and 3 John, Jude, and the Apocalypse – but the whole of the Catholic Epistles. These were at a later date translated and received into the Syriac Canon of the New Testament, as the quotations of the early Syrian Fathers take no notice of these New Testament writings.

From the 5th century, however, the Peshitta containing both Old Testament and New Testament has been used in its present form as the national version of the Syriac Scriptures only. The translation of the New Testament is careful, faithful and literal, and the simplicity, directness and transparency of the style are admired by all Syriac scholars and have earned it the title of "Queen of the versions."[1]

5. Old Syriac Texts

It is in the gospels, however, that the analogy between the Latin Vulgate and the Syriac Vulgate can be established by evidence. If the Peshitta is the result of a revision as the Vulgate was, then we may expect to find Old Syriac texts answering to the Old Latin. Such texts have actually been found: three texts have been recovered, all showing divergences from the Peshitta, and believed by competent scholars to be older than it, and therefore better translations for use in text criticism. These are, to take them in the order of their recovery, (1) the Curetonian Syriac, (2) the Syriac of Tatian's Diatessaron, and (3) the Sinaitic Syriac.[1]

- Details on Curetonian

The Curetonian consists of fragments of the gospels brought in 1842 from the Nitrian Desert in Egypt and now in the British Museum. The fragments were examined and edited by Canon Cureton of Westminster in 1858. The manuscript from which the fragments have come appears to belong to the 5th century, but scholars believe the text itself may be as old as the 100's CE. In this recension, the gospel according to Matthew has the title "Evangelion da-Mepharreshe", which will be explained in the next section.

- Details on Tatian's Diatessaron

The Diatessaron is the work which Eusebius ascribes to Tatian, an early Christian author considered by some to have been a heretic. Eusebius called it that "combination and collection of the Gospels, I know not how, to which he gave the title Diatessaron." (Ecclesiastical History book 4, 29:6) It is the earliest harmony of the four gospels known to us. Its existence is amply attested in the churches of Mesopotamia and Syria, but it had disappeared for centuries, and not a single copy of the Syriac work survives.

A commentary upon it by Ephraem the Syrian, surviving in an Armenian translation, was issued by the Mechitarist Fathers at Venice in 1836, and afterward translated into Latin. Since 1876, an Arabic translation of the Diatessaron itself has been discovered, and it has been ascertained that the Codex Fuldensis of the Vulgate represents the order and contents of the Diatessaron. A translation from the Arabic can now be read in English in J. Hamlyn Hill's The Earliest Life of Christ Ever Compiled from the Four Gospels.

Although no copy of the Diatessaron has survived, the general features of Tatian's Syriac work can be gathered from these materials. It is still a matter of dispute whether Tatian composed his "Harmony" out of a Syriac version already made, or composed it first in Greek and then translated it into Syriac. But the existence and widespread use of a harmony, i.e. combining all four gospels in one, from such an early period (172 AD), enables us to understand the title "Evangelion da-Mepharreshe". It means "the Gospel of the Separated," and points to the existence of single gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, John, in Syriac, in contradistinction to Tatian's Harmony. Theodoret, bishop of Cyrrhus in the 5th century CE, tells how he found more than 200 copies of the Diatessaron held in honor in his diocese and how he collected them, and put them out of the way, associated as they were with the name of a heretic, and substituted for them the Gospels of the four evangelists in their separate forms.

- Sinaitic Syriac

In 1892 the discovery of the third text comprising the four Gospels nearly entire, known as the Sinaitic Syriac, based on the place where it was found, heightened the interest in the subject and increased the available material. It is a palimpsest, and was found in the Monastery of Catherine on Mt. Sinai by Agnes S. Lewis and her sister Margaret D. Gibson. The text has been carefully examined and many scholars regard it as representing the earliest translation into Syriac, and reaching back into the 2nd century. Like the Curetonian, it is an example of the "Evangelion da-Mepharreshe" as distinguished from the Harmony of Tatian.

- Relation to Peshitta

The discovery of these texts has raised many questions which may require further discovery and investigation to answer satisfactorily. It is natural to ask what the relation of these three texts is to the Peshitta. There are still scholars who maintain the priority of the Peshitta and insist upon its claim to be the earliest monument of Syrian Christianity, foremost of whom is G. H. Gwilliam, the learned editor of the Oxford Peshito.[5] But, the progress of the investigation into Syriac Christian literature points distinctly the other way. From an exhaustive study of the quotations in the earliest Syriac Fathers and the works of Ephraem Syrus, in particular, Burkitt concludes that the Peshitta did not exist in the 4th century. He finds that Ephraem used the Diatessaron in the main as the source of his quotation, although "his voluminous writings contain some clear indications that he was aware of the existence of the separate Gospels, and he seems occasionally to have quoted from them.[6] Such quotations as are found in other extant remains of Syriac literature before the 5th century bear a greater resemblance to the readings of the Curetonian and the Sinaitic than to the readings of the Peshitta. Internal and external evidence alike point to the later and revised character of the Peshitta.

6. Brief History of the Peshitta

The Peshitta had from the 5th century onward a wide circulation in the East, and was accepted and honored by the whole diversity of sects of Syriac Christianity. It had a great missionary influence: the Armenian and Georgian versions, as well as the Arabic and the Persian, owe not a little to the Syriac. The famous Nestorian tablet of Chang'an witnesses to the presence of the Syriac scriptures in the heart of China in the 8th century. The Peshitta was first brought to the West by Moses of Mindin, a noted Syrian ecclesiastic who unsuccessfully sought a patron for the work of printing it in Rome and Venice. However, he was successful in finding such a patron in the Imperial Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire at Vienna in 1555—Albert Widmanstadt. He undertook the printing of the New Testament, and the emperor bore the cost of the special types which had to be cast for its issue in Syriac. Immanuel Tremellius, the converted Jew whose scholarship was so valuable to the English reformers and divines, made use of it, and in 1569 issued a Syriac New Testament in Hebrew letters. In 1645, the editio princeps of the Old Testament was prepared by Gabriel Sionita for the Paris Polyglot, and in 1657 the whole Peshitta found a place in Walton's London Polyglot. For long the best edition of the Peshitta was that of John Leusden and Karl Schaaf, and it is still quoted under the symbol "Syrschaaf", or "SyrSch". The critical edition of the gospels recently issued by G. H. Gwilliam at the Clarendon Press is based upon some 50 manuscripts. Considering the revival of Syriac scholarship, and the large company of workers engaged in this field, we may expect further contributions of a similar character to a new and complete critical edition of the Peshitta.[1]

7. Old Testament Peshitta

The Peshitta version of the Old Testament is an independent translation based largely on a Hebrew text similar to the Proto-Masoretic Text. It shows a number of linguistic and exegetical similarities to the Targumim but is no longer thought to derive from them. In some passages, the translators have clearly used the Greek Septuagint. The influence of the Septuagint is particularly strong in Isaiah and the Psalms, probably due to their use in the liturgy. Most of the Deuterocanonicals are translated from the Septuagint, and the translation of Sirach was based on a Hebrew text.

The choice of books included in the Old Testament Peshitta changes from one manuscript to another, though most of the Deuterocanonicals are usually present. Biblical apocryphas, as 1 Esdras, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, Psalm 151 can be also found in some manuscripts. The manuscript of Biblioteca Ambrosiana, discovered in 1866, includes also 2 Baruch (Syriac Apocalypse of Baruch).

7.1. Books of the Peshitta Old Testament

| UBS Order | Syriac Name | English Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܒܪܝܫܝܬ | Genesis |

| 2 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܦܩܢܐ | Exodus |

| 3 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܟܗ̈ܢܐ | Leviticus |

| 4 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܢ̇ܝܢܐ | Numbers |

| 5 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܬܢ̇ܝܢ ܢܡܘܣܐ | Deuteronomy |

| 6 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܐܝܘܒ | Job |

| 7 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܝܫܘܥ ܒܪ ܢܘܢ | Joshua |

| 8 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܕܝܢ̈ܐ ܕܒܢ̈ܝ ܐܝܣܪܐܝܠ | Judges |

| 9 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܫܡܘܐܝܠ ܢܒܝܐ ܩܕܡܝܐ | 1 Samuel |

| 10 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܫܡܘܐܝܠ ܢܒܝܐ ܕܬܪܝܢ | 2 Samuel |

| 11 | ܣܦܪܐ ܩܕܡ ܕܡܠܟ̈ܐ | 1 Kings |

| 12 | ܣܦܪܐ ܬܪܝܢ ܕܡܠ̈ܟܐ | 2 Kings |

| 13 | ܣܦܪܐ ܩܕܡܝܐ ܕܒܪܝܡܝܢ | 1 Chronicles |

| 14 | ܣܦܪܐ ܬܪܝܢ ܕܒܪܝܡܝܢ | 2 Chronicles |

| 15 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܙܡܘܪ̈ܐ | Psalms |

| 16 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡ̈ܬܠܐ ܕܫܠܝܡܘܢ | Proverbs |

| 17 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܩܘܗܠܬ | Ecclesiastes |

| 18 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܪܥܘܬ ܡܘܐܒܝܬܐ | Ruth |

| 19 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܬܫܒܚܬ ܬܫܒ̈ܚܬܐ | Song of Songs |

| 20 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܐܣܬܝܪ | Esther |

| 21 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܥܙܪܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Ezra |

| 22 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܢܚܡܝܐ | Nehemiah |

| 23 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܐܫܥܝܐ ܒܪ ܐܡܘܨ | Isaiah |

| 24 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܗܘܫܥ ܢܒܝܐ | Hosea |

| 25 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܝܘܝܠ ܢܒܝܐ | Joel |

| 26 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܥܡܘܣ ܢܒܝܐ | Amos |

| 27 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܥܘܒܕܝܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Obadiah |

| 28 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܝܘܢܢ ܢܒܝܐ | Jonah |

| 29 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܝܟܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Micah |

| 30 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܢܚܘܡ ܢܒܝܐ | Nahum |

| 31 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܚܒܩܘܩ ܢܒܝܐ | Habbakuk |

| 32 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܨܦܢܝܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Zephaniah |

| 33 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܚܓܝ ܢܒܝܐ | Haggai |

| 34 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܙܟܪܝܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Zechariah |

| 35 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܠܐܟܝ ܢܒܝܐ | Malachi |

| 36 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܐܪܡܝܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Jeremiah |

| 37 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܐܘ̈ܠܝܬܗ ܪܐܪܡܝܐ ܢܒܝܐ | Lamentations |

| 38 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܚܙܩܝܐܠ ܢܒܝܐ | Ezekiel |

| 39 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܕܢܝܐܠ ܢܒܝܐ | Daniel |

| UBS Order | Syriac Name | English Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܛܘܒܝܛ | Tobit |

| 2 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܝܗܘܕܝܬ | Judith |

| 3 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܐܣܬܝܪ | Additions to Esther |

| 4 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܚܟܡܬܐ ܪܒܬܐ | Wisdom |

| 5 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܝܫܘܥ ܒܪ ܐܣܝܪܐ | Sirach |

| 6 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܐܪܡܝܐ | Letter of Jeremiah |

| 7 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܒܪܘܟ ܣܦܪܐ | Baruch |

| 8 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܬܪܬܝܢ ܕܒܪܘܟ ܣܦܪܐ | 2 Baruch |

| 9 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܕܢܝܐܝܠ (ܕܫܘܫܢ) | Additions to Daniel |

| 10 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܩ̈ܒܝܐ: ܐ | 1 Maccabees |

| 11 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܩ̈ܒܝܐ: ܒ | 2 Maccabees |

7.2. Main manuscripts

More than 250 manuscripts of the Old Testament Peshitta are known, and the main and older ones are:

- London, British Library, Add. 14,425 (also referred to as "5b1" in Leiden numeration), which is dated to the second half of 5th century. The manuscript includes only Genesis, Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy, and the text is more similar to the Masoretic Text than the text of most other manuscripts, even if somewhere 5b1 has relevant differences.

- Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, B. 21 inf Codex Ambrosianus (also referred to as "7a1"), discovered by Antonio Ceriani in 1866 and published in 1876–1883. 7a1 dates from the 6th or the 7th century. In 1006/7 it became part of the library of the Syrian Monastery in Egypt, and in the 17th century was moved to Milan. It is the base text of the critical edition of Peshitta Institute of Leiden, and includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible as well as Wisdom, Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Sirach, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 2 Baruch (the only extant manuscript in Syriac) with the Letter of Baruch, 2 Esdras, and the second book of The Jewish War[8]

- Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, Syr. 341 (also referred to as "8a1"), dating from the 8th century or prior with many corrections, it includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Wisdom (of Solomon), Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Sirach, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, 3 Maccabees, Odes, Prayer of Manasseh, and Letter of Baruch[8]

- Florence, Laurentian Library, Or. 58 (also referred to as "9a1"), this manuscript has a text more similar to the Masoretic Text like what 5b1 has, and scholars don't know if this is a more original text than 5b1, or due to later corrections. It includes all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Prayer of Manasseh[8]

- Cambridge, University Library, Oo.I.1,2 (also referred to as "12a1" or as "Buchanan Bible"), a 12th-century CE manuscript that probably originated in Tur Abdin area and was later moved to India . In the early 19th century, it was ultimately taken to Cambridge by Claudius Buchanan. This manuscript is the best witness of an important textual family, including all the books of the Hebrew Bible and Wisdom (of Solomon), Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, Judith, Sirach, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, Tobit, 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, and Letter of Baruch[8]

- Baghdad, Library of Chaldean Patriarchate, 211 (Mosul cod. 4), a 12th-century CE manuscript used often as base text for Psalms 152–155.

7.3. Early Print Editions

- Paris Polyglot, 1645, edited by Gabriel Sionita and probably based on manuscript "17a5", is considered today a recent and unreliable manuscript.

- London Polyglot, 1657, based on the Paris Polyglot text with an appendix of some collations from other manuscripts kept in Oxford ranging from the 12th to the 17th century CE.

- Samuel Lee edition, which was first printed in London in 1823 by the British and Foreign Bible Society and reprinted in 1826. The text is almost like the text of the London Polyglot, but in the 1826 reprinting, the British and Foreign Bible Society decided to cut the page containing Psalm 151 from the edition, as it is not included in the Protestant canon, even going so far as to cut the page from previously printed editions.[9]

- Urmia Bible, published in 1852 by Justin Perkins. It also included a parallel translation in the Urmian dialect of the Assyrian Neo-Aramaic language.

- Mosul edition, published in 1888–1892 by Clement Joseph David [10] and by Mar Georges Ebed-Iesu Khayyath for the Dominican mission. This edition, differently from previous editions, includes some books not included in the Hebrew Bible but found in many Peshitta manuscripts. Books included are: Tobit, Judith, the additions to Esther, Wisdom, Sirach, the Letter of Jeremiah, Baruch, Bel and the Dragon, Susanna, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, and 2 Baruch with the Letter of Baruch.

8. New Testament Peshitta

The Peshitta version of the New Testament is thought to show a continuation of the tradition of the Diatessaron and Old Syriac versions, displaying some lively 'Western' renderings (particularly clear in the Acts of the Apostles). It combines this with some of the more complex 'Byzantine' readings of the 5th century CE. It contains the unusual feature of the absence of 2 Peter, 2 John, 3 John, Jude, and Revelation, however, modern Syriac Bibles add 6th- or 7th-century translations of these five books to a revised Peshitta text.

With this understood, almost all Syriac scholars agree that the Peshitta gospels are translations of the Greek originals. However, there is a minority viewpoint in scholarship that the Aramaic New Testament of the Peshitta represents the original New Testament and the Greek is a translation of it. The type of text represented by Peshitta is the Byzantine. In a detailed examination of Matthew 1–14, Gwilliam found that the Peshitta agrees with the Textus Receptus only 108 times and with Codex Vaticanus 65 times. Meanwhile, in 137 instances it differs from both, usually with the support of the Old Syriac and the Old Latin, and in 31 instances it stands alone.[11]

To this end, and in reference to the originality of the Peshitta, the words of Patriarch Shimun XXI Eshai are summarized as follows:

- "With reference to....the originality of the Peshitta text, as the Patriarch and Head of the Holy Apostolic and Catholic Church of the East, we wish to state, that the Church of the East received the scriptures from the hands of the blessed Apostles themselves in the Aramaic original, the language spoken by our Lord Jesus Christ Himself, and that the Peshitta is the text of the Church of the East which has come down from the Biblical times without any change or revision."[12]

In the first century CE, Josephus, the Jewish priest, testified that Aramaic was widely spoken and understood accurately by Parthians, Babylonians, the remotest Arabians, and those of his nation beyond Euphrates with Adiabeni. He says:

"I have proposed to myself, for the sake of such as live under the government of the Romans, to translate those books into the Greek tongue, which I formerly composed in the language of our country, and sent to the Upper Barbarians. Joseph, the son of Matthias, by birth a Hebrew, a priest also, and one who at first fought against the Romans myself, and was forced to be present at what was done afterwards, [am the author of this work],"

Jewish Wars (Book 1, Preface, Paragraph 1)(1:3)

and continuing,

"I thought it therefore an absurd thing to see the truth falsified in affairs of such great consequence, and to take no notice of it; but to suffer those Greeks and Romans that were not in the wars to be ignorant of these things, and to read either flatteries or fictions, while the Parthians, and the Babylonians, and the remotest Arabians, and those of our nation beyond Euphrates, with the Adiabeni, by my means, knew accurately both whence the war begun, what miseries it brought upon us, and after what manner it ended."

Jewish Wars (Book 1 Preface, Paragraph 2) (1:6)

Yigael Yadin, an archeologist working on the Qumran find, also agrees with Josephus' testimony, pointing out that Aramaic was the lingua franca of this time period.[13] Josephus' testimony on Aramaic is also supported by the gospel accounts of the New Testament (specifically in Matthew 4:24-25, Mark 3:7-8, and Luke 6:17), in which people from Galilee, Judaea, Jerusalem, Idumaea, Tyre, Sidon, Syria, Decapolis, and "from beyond Jordan" came to see Jesus for healing and to hear his discourse.

8.1.Books of the Peshitta New Testament

Note: The following list does not necessarily reflect the historical canonicity or typical order of New Testament books in the Peshitta translation.

| UBS Order | Syriac Name | English Name |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܬܝ | Matthew |

| 2 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܡܪܩܘܣ | Mark |

| 3 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܠܘܩܘܣ | Luke |

| 4 | ܣܦܪܐ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ | John |

| 5 | ܦܪܟܣܣ ܕܫܠܝ̈ܚܐ | Acts |

| 6 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܪ̈ܗܘܡܝܐ | Romans |

| 7 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܩܘܪ̈ܝܢܬܝܐ ܩܕܡܝܬܐ | 1 Corinthians |

| 8 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܩܘܪ̈ܝܢܬܝܐ ܕܬܪܬܝܢ | 2 Corinthians |

| 9 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܓܠܛܝ̈ܐ | Galatians |

| 10 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܐܦܣܝ̈ܐ | Ephesians |

| 11 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܦܝܠܝܦܣܝ̈ܐ | Philippians |

| 12 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܩܘܠ̈ܣܝܐ | Colossians |

| 13 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܬܣܠ̈ܘܢܝܩܝܐ ܩܕܡܝܬܐ | 1 Thessalonians |

| 14 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܬܣܠ̈ܘܢܝܩܝܐ ܕܬܪܬܝܢ | 2 Thessalonians |

| 15 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܛܝܡܬܐܘܣ ܩܕܡܝܬܐ | 1 Timothy |

| 16 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܛܝܡܬܐܘܣ ܕܬܪܬܝܢ | 2 Timothy |

| 17 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܛܝܛܘܣ | Titus |

| 18 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܘܠܘܣ ܕܠܘܬ ܦܝܠܝܡܘܢ | Philemon |

| 19 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܠܘܬ ܥܒܪ̈ܝܐ | Hebrews |

| 20 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܝܥܩܘܒ ܫܠܝܚܐ | James |

| 21 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܦܛܪܘܣ ܫܠܝܚܐ | 1 Peter |

| 22 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܬܪܬܝܢ ܕܦܛܪܘܣ | 2 Peter |

| 23 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ ܫܠܝܚܐ | 1 John |

| 24 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܬܪܬܝܢ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ | 2 John |

| 25 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܬܠܬ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ | 3 John |

| 26 | ܐܓܪܬܐ ܕܝܗܘܕܐ | Jude |

| 27 | ܓܠܝܢܐ ܕܝܘܚܢܢ | Revelation |

9. Critical Edition of the New Testament

The standard United Bible Societies 1905 edition of the New Testament of the Peshitta was based on editions prepared by Syriacists Philip E. Pusey (d.1880), George Gwilliam (d.1914) and John Gwyn.[14] These editions comprised Gwilliam & Pusey's 1901 critical edition of the gospels, Gwilliam's critical edition of Acts, Gwilliam & Pinkerton's critical edition of Paul's Epistles and John Gwynn's critical edition of the General Epistles and later Revelation. This critical Peshitta text is based on a collation of more than seventy Peshitta and a few other Aramaic manuscripts. All 27 books of the common Western Canon of the New Testament are included in this British & Foreign Bible Society's 1905 Peshitta edition, as is the adultery pericope (John 7:53–8:11). The 1979 Syriac Bible, United Bible Society, uses the same text for its New Testament. The Online Bible reproduces the 1905 Syriac Peshitta NT in Hebrew characters.

10. Translations of the Peshitta

- James Murdock- The New Testament, Or, The Book of the Holy Gospel of Our Lord and God, Jesus the Messiah (1851).

- John Wesley Etheridge- A Literal Translation of the Four Gospels From the Peschito, or Ancient Syriac and The Apostolical Acts and Epistles From the Peschito, or Ancient Syriac: To Which Are Added, the Remaining Epistles and The Book of Revelation, After a Later Syriac Text (1849).

- George M. Lamsa- The Holy Bible From the Ancient Eastern Text (1933)- Contains both the Old and New Testaments according to the Peshitta text. This translation is better known as the Lamsa Bible. He also wrote several other books on the Peshitta and Aramaic primacy such as Gospel Light, New Testament Origin, and Idioms of the Bible, along with a New Testament commentary. To this end, several well-known Evangelical Protestant preachers have used or endorsed the Lamsa Bible, such as Oral Roberts, Billy Graham, and William M. Branham.

- Andrew Gabriel Roth- Aramaic English New Testament (AENT), which includes a literal translation of the Peshitta on the left side pages with the Aramaic text in Hebrew characters on the right side with Roth's commentary. The AENT is essentially a revision of the Younan Interlinear New Testament (from Matthew 1 to Acts 15) and James Murdock's (Acts 15 and onward).[15]

- Andumalil Mani Kathanar - Vishudha Grantham. New Testament translation in Malayalam.

- Mathew Uppani C. M. I - Peshitta Bible. Translation (including Old and New Testaments) in Malayalam (1997).

- Arch-corepiscopos Curien Kaniamparambil- Vishudhagrandham. Translation (including Old and New Testaments) in Malayalam.

- Janet Magiera- Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation, Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Translation- Messianic Version, and Aramaic Peshitta New Testament Vertical Interlinear (in three volumes)(2006). Magiera is connected to George Lamsa.

- Rev. Glenn David Bauscher- The Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament (1st edition 2006), Psalms, Proverbs & Ecclesiastes (4th edition 2011) [16] the basis for The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English (2007, 6th edition 2011). Another literal translation that comes as an interlinear New Testament (with Hebrew characters), and a smoother English version. Bauscher translated from the Western Peshitto text.[17]

- Victor Alexander- Aramaic New Testament and Disciples New Testament. Alexander is a native speaker of Syriac.

- The Way International- Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament

- Paul Younan, a native Syriac speaker, is currently working on an interlinear translation of the Peshitta into English.

- Herb Jahn of Exegesis Bibles translated the Western Peshitto in Aramaic New Covenant.

- A. Francis Werner- Ancient Roots Translinear Bible: New Testament

- William Norton- A Translation, in English Daily Used, of the Peshito-Syriac Text, and of the Received Greek Text, of Hebrews, James, 1 Peter, and 1 John: With An Introduction On the Peshito-Syriac Text, and the Received Greek Text of 1881 and A Translation in English Daily Used: of the Seventeen Letters Forming Part of the Peshito-Syriac Books. William Norton was a Peshitta primacist, as shown in the introduction to his translation of Hebrews, James, I Peter, and I John.

- James Scott Trimm- Hebraic-Roots Version "New Testament". In Matthew, Trimmm utilizes the various Hebrew versions of Matthew and the Old Syriac texts. The other three Gospels are translated from the Old Syriac Gospels, while the rest of the New Testament uses the Peshitta. Trimm has been accused of plagiarizing The Way International's Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament.

- Lonnie Martin- The Testimony of Yeshua. This is a revision of the Etheridge and Murdock translations.

- Joseph Pashka- Aramaic Gospels and Acts and Aramaic Gospels & Acts Companion. The translation includes both the Peshitta text (following he 1905 Critical Text) and a translation of it. The Companion transliterates the Aramaic text without vowels.

- Gorgias Press - Antioch Bible, a Peshitta text and translation of the Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha.

In Spanish exists Biblia Peshitta en Español (Spanish Peshitta Bible) by Holman Bible Publishers, Nashville, TN. U. S. A., published 2007.

11. Manuscripts of the New Testament

The following manuscripts are in the British Archives:

- British Library, Add. 14470 – complete text of 22 books, from the 5th/6th century

- Rabbula Gospels

- Khaboris Codex

- Codex Phillipps 1388

- British Library, Add. 12140

- British Library, Add. 14479

- British Library, Add. 14455

- British Library, Add. 14466

- British Library, Add. 14467

- British Library, Add. 14669

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Religion:Peshitta

References

- Syriac Versions of the Bible by Thomas Nicol http://www.bible-researcher.com/syriac-isbe.html

- Eberhard Nestle in Hastings' Dictionary of the Bible, IV, 645b.

- Francis Crawford Burkitt, Early Eastern Christianity, 71 ff. 1904. https://books.google.com/books?id=vssdKNm9Hm4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=Early+Eastern+Christianity&hl=en&ei=UYLZTZz7CMa08QPHnbGUAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=edessa&f=false

- Historia Ecclesiastica, IV, xxii

- Tetraevangelium sanctum, Clarendon Press, 1901

- Evangelion da-Mepharreshe, 186.

- ܟܬܒܐ ܩܕܝ̈ܫܐ: ܟܬܒܐ ܕܕܝܬܩܐ ܥܛܝܼܩܬܐ ܘ ܚ̇ܕܬܐ. [London]: United Bible Societies. 1979. pp. Table of Contents. OCLC 38847449. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/38847449

- For the order of the books see S. Brock, The Bible in the Syriac Tradition ISBN:1-59333-300-5 p. 116

- A. S. van der Woude In Quest of the Past ISBN:90-04-09192-0 (1988), p. 70

- Syriac Catholic Archbishop of Damascus, born 1829

- Bruce M. Metzger, The Early Versions of the New Testament: Their Origin, Transmission and Limitations (Oxford University Press 1977), p. 50.

- His Holiness Mar Eshai Shimun, Catholicos Patriarch of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Church of the East. April 5, 1957

- "Bar Kokhba: The rediscovery of the legendary hero of the last Jewish Revolt Against Imperial Rome", 234

- Corpus scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium: Subsidia Catholic University of America, 1987 "37 ff. The project was founded by Philip E. Pusey who started the collation work in 1872. However, he could not see it to completion since he died in 1880. Gwilliam,

- Andrew Gabriel Roth, Aramaic English New Testament, Netzari Press, Third Edition (2010), ISBN:1-934916-26-9 – included all twenty-seven books of the Aramaic New Testament, as a literal translation of the very oldest known Aramaic New Testament texts. This is a study Bible with over 1700 footnotes and 350 pages of appendixes to help the reader understand the poetry, idioms, terms and definitions in the language of Y'shua (Jesus) and his followers. The Aramaic is featured with Hebrew characters and vowel pointing.

- The Aramaic-English Interlinear New Testament 4th edition 2011

- The Original Aramaic New Testament in Plain English, 6th edition 2011 has also Psalms & Proverbs in plain English from his Peshitta interlinear of those Peshitta Old Testament books, according to Codex Ambrosianus (6th century?) and Lee's 1816 edition of the Peshitta Old Testament. Bauscher has also published an Aramaic-English & English Aramaic Dictionary & nine other books related to the Peshitta Bible. The interlinear displays the Aramaic in Ashuri (square Hebrew) letters. Bauscher also has an Interlinear of the Peshitta Torah titled: The Aramaic English Interlinear Peshitta Old Testament (The Torah).