Paan (from Sanskrit: पर्ण, romanized: parṇá, lit. leaf, cognate with English fern) is a preparation combining betel leaf with areca nut widely consumed throughout South Asia and East Asia (mainly Taiwan). It is chewed for its stimulant effects. After chewing, it is either spat out or swallowed. Paan has many variations. Slaked lime (chuna) paste is commonly added to bind the leaves. Some preparations in the Indian subcontinent include katha paste or mukhwas to freshen the breath. Magahi paan is an expensive variety of betel which is grown in Aurangabad, Gaya and Nalanda districts of central Bihar. It is non-fibrous, sweeter, tastier and the softest of the lot. The origin and diffusion of betel chewing originates from and is closely tied to the Neolithic expansion of the Austronesian peoples. It was spread to the Indo-Pacific during prehistoric times, reaching Near Oceania at 3,400 to 3,000 BP; South India and Sri Lanka by 3,500 BP; Mainland Southeast Asia by 3,000 to 2,500 BP; Northern India by 1500 BP; and Madagascar by 600 BP. From India, it was also spread westwards to Persia and the Mediterranean. Paan (under a variety of names) is also consumed in many other Asian countries and elsewhere in the world by some Asian emigrants, with or without tobacco. It can be an addictive and stimulating formulation with adverse health effects, both with and without tobacco. The spit from chewing betel nuts, known as "buai pekpek" in Papua New Guinea, is often considered an eyesore. Because of this, many places have banned selling and chewing "buai".

- betel leaf

- betel

- areca nut

1. History

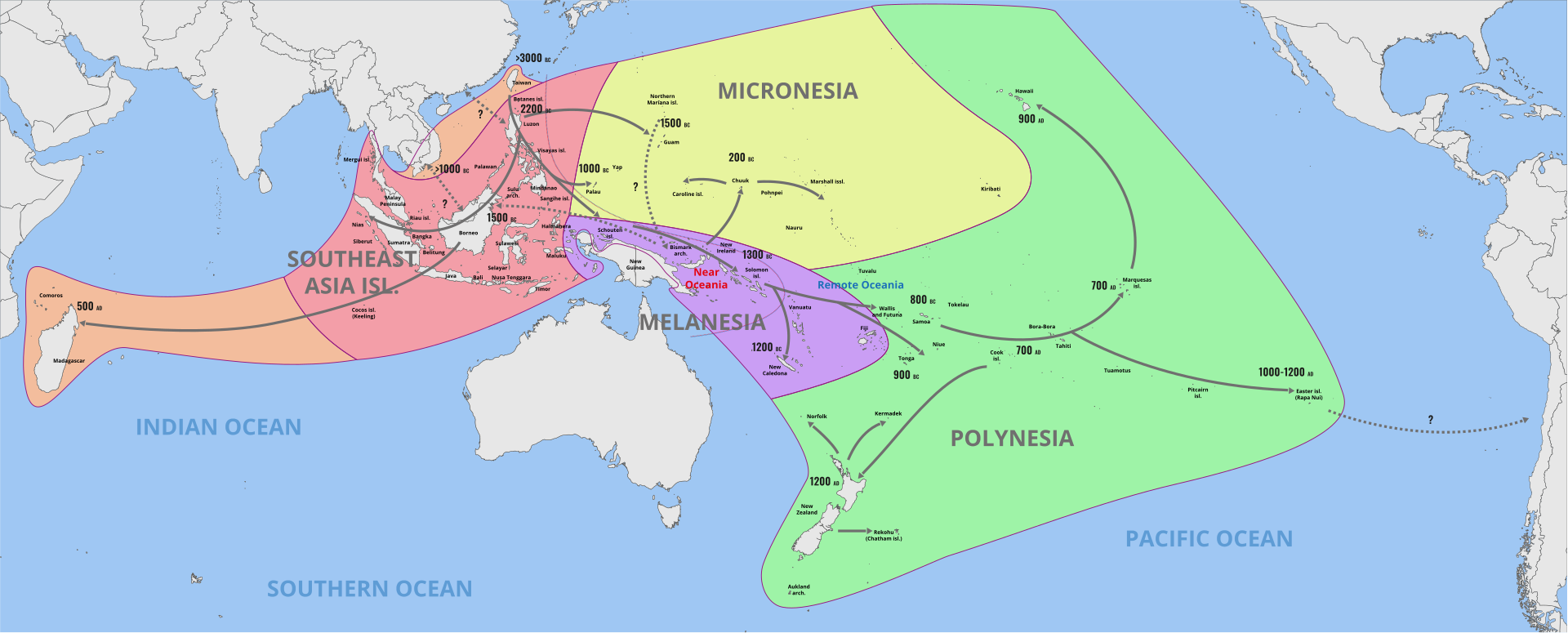

Based on archaeological, linguistic, and botanical evidence, the spread of betel chewing is most strongly associated with the Austronesian peoples. Chewing betel requires the combination of areca nut (Areca catechu) and betel leaf (Piper betle). Both plants are native from the region between Island Southeast Asia to Australasia. A. catechu is believed to be originally native to the Philippines , where it has the greatest morphological diversity as well as the most closely related endemic species. The origin of the domestication of Piper betle, however, is unknown. It is also unknown when the two were combined, as areca nut alone can be chewed for its narcotic properties.[1] In eastern Indonesia, leaves from the wild Piper caducibracteum are also harvested and used in place of betel leaves.[2]

Map showing the migration and expansion of the Austronesians (5,500 to 800 BP), which roughly corresponds to the prehistoric distribution of betel chewing. By Pavljenko - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116424449

Map showing the migration and expansion of the Austronesians (5,500 to 800 BP), which roughly corresponds to the prehistoric distribution of betel chewing. By Pavljenko - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116424449The oldest unequivocal evidence of betel chewing is from the Philippines. Specifically that of several individuals found in a burial pit in the Duyong Cave site of Palawan island dated to around 4,630±250 BP. The dentition of the skeletons is stained, typical of betel chewers. The grave also includes Anadara shells used as containers of lime, one of which still contained lime. Burial sites in Bohol dated to the first millennium CE also show the distinctive reddish stains characteristic of betel chewing. Based on linguistic evidence of how the reconstructed Proto-Austronesian term *buaq originally meaning "fruit" came to refer to "areca nut" in Proto-Malayo-Polynesian, it is believed that betel chewing originally developed somewhere within the Philippines shortly after the beginning of the Austronesian expansion (~5,000 BP). From the Philippines, it spread back to Taiwan, as well as onwards to the rest of Austronesia.[1]

There are very old claims of betel chewing dating to at least 13,000 BP at the Kuk Swamp site in New Guinea, based on probable Areca sp. recovered. However, it is now known that these might have been due to modern contamination of sample materials. Similar claims have also been made at other older sites with Areca sp. remains, but none can be conclusively identified as A. catechu and their association with betel peppers is tenuous or nonexistent.[1]

It reached Micronesia at around 3,500 to 3,000 BP with the Austronesian voyagers, based on both linguistic and archaeological evidence.[3] It was also previously present in the Lapita culture, based on archaeological remains from Mussau dated to around 3,600 to 2,500 BP. But it did not reach Polynesia further east. It is believed that it stopped in the Solomon Islands due to the replacement of betel chewing with the tradition of kava drinking prepared from the related Piper methysticum.[4][5] It was also diffused into East Africa via the Austronesian settlement of Madagascar and the Comoros by around the 7th century.[1]

The practice also diffused to the cultures the Austronesians had historical contact with. It reached the Dong Son culture via the Austronesian Sa Huỳnh culture of Vietnam at around 3,000 to 2,500 BP through trade contacts with Borneo. It is from this period that skeletons with characteristic red-stained teeth start to appear in Mainland Southeast Asia. It is assumed that it reached South China and Hainan at around the same time, though no archaeological evidence for this can be found as of yet. In Cambodia, the earliest evidence of betel nut chewing is from around 2,400 to 2,200 BP. It also spread to Thailand at 1,500 BP, based on archaeobotanical evidence.[1]

In the Indian subcontinent, betel chewing was introduced through early contact of Austronesian traders from Sumatra, Java, and the Malay Peninsula with the Dravidian-speakers of Sri Lanka and southern India at around 3,500 BP. This also coincides with the introduction of Southeast Asian plants like Santalum album and Cocos nucifera, as well as the adoption of the Austronesian outrigger ship and crab-claw sail technologies by Dravidian-speakers. Unequivocal literary references to betel only start appearing after the Vedic period, in works like Dipavaṃsa (c. 3rd century CE) and Mahāvaṃsa (c. 5th century). Betel chewing only reached northern India and Kashmir after 500 CE through trade with Mon-Khmer-speaking peoples in the Bay of Bengal. From there it followed the Silk Road to Persia and into the Mediterranean.[1][6]

Chinese records, specifically Linyi Ji by Dongfang Shuo associate the growing of areca palms with the first settlers of the Austronesian Champa polities in southern Vietnam at around 2,100 to 1,900 BP. This association is echoed in Nanfang Cao Mu Zhuang by Ji Han (c. 304 CE) who also describes its importance in Champa culture, specifically in the way Cham hosts traditionally offer it to guests. Betel chewing entered China through trade with Champa, borrowing the Proto-Malayo-Chamic name *pinaŋ resulting in Chinese bin lang for "areca nut", with the meaning of "honored guest", reflecting Chamic traditions. The same for the alternate term bin men yao jian, literally meaning "guest [at the door] medicinal sweetmeat".[1]

2. Culture

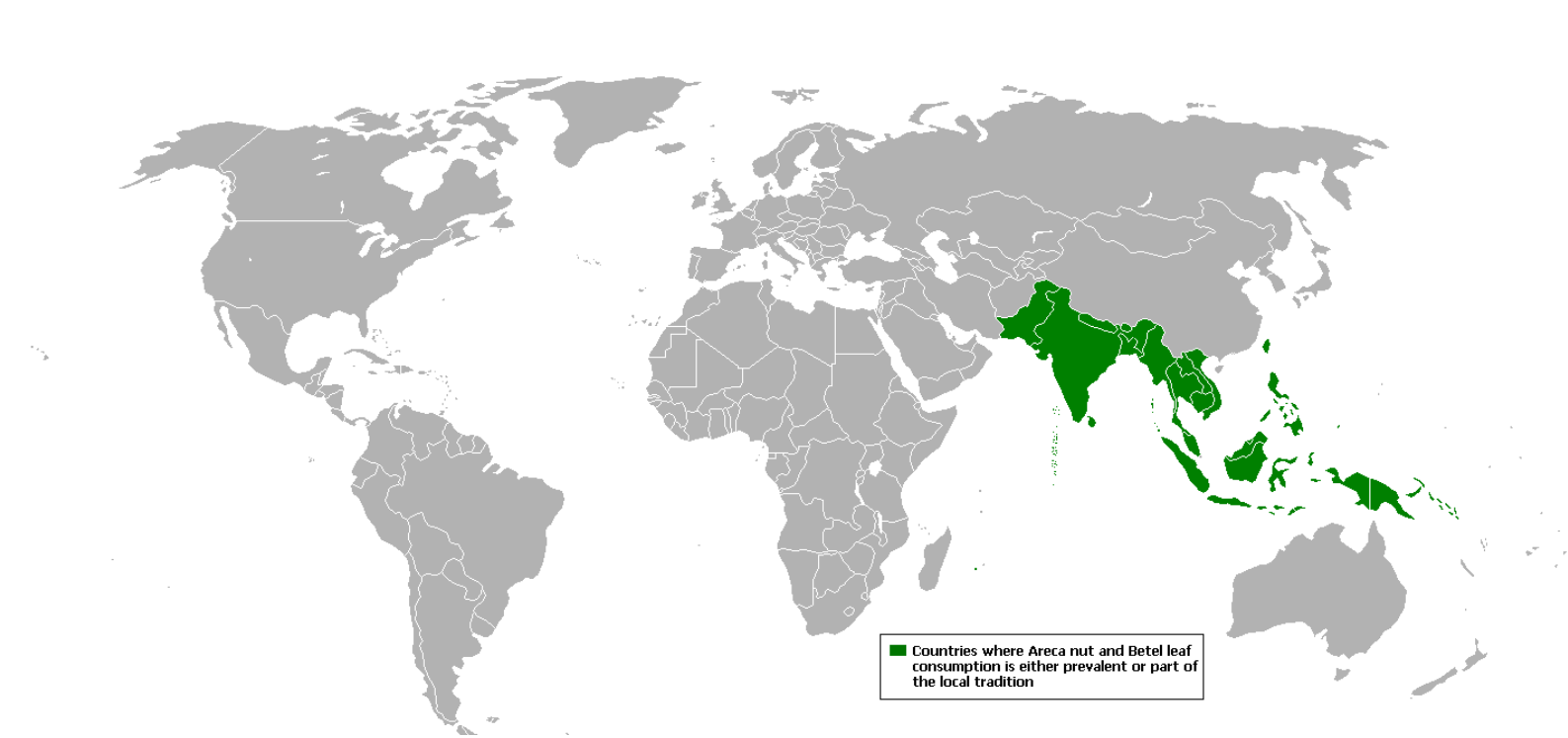

Betel leaf and areca nut consumption in the world. By Mohonu at English Wikipedia - Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons by Vinhtantran using CommonsHelper., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6767708

Paan preparation, Myanmar. By © Vyacheslav Argenberg / http://www.vascoplanet.com/, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=98529020

Beeda stall, Gallface Beach, Colombo. By Shamli071 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17594056

Paan made with areca nut and lime, with or without tobacco, causes profuse red coloured salivation. This saliva is spat, yielding stains and biological waste pollution in public spaces. Many countries and municipalities have laws to prevent paan spit.[7][8] By Anna Frodesiak - Own work, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=18231962

Chewing the mixture of areca nut and betel leaf is a tradition, custom or ritual which dates back thousands of years from India to the Pacific. Ibn Battuta describes this practice as follows: "The betel is a tree which is cultivated in the same manner as the grape-vine; ... The betel has no fruit and is grown only for the sake of its leaves ... The manner of its use is that before eating it one takes areca nut; this is like a nutmeg but is broken up until it is reduced to small pellets, and one places these in his mouth and chews them. Then he takes the leaves of betel, puts a little chalk on them, and masticates them along with the betel." Since the introduction of tobacco from the Western Hemisphere to the Eastern Hemisphere, it has been an optional addition to paan.

Paan chewing constitutes an important and popular cultural activity in many Asian and Oceanic countries, including India , Myanmar, Cambodia, the Solomon Islands, Thailand, the Philippines , Laos, and Vietnam.[9]

In urban areas, chewing paan is generally considered a nuisance because some chewers spit the paan out in public areas – compare chewing gum ban in Singapore and smoking ban. The red stain generated by the combination of ingredients when chewed are known to make a colourful stain on the ground. This is becoming an unwanted eyesore in Indian cities such as Mumbai, although many see it as an integral part of Indian culture. This is also common in some of the Persian Gulf countries, such as the UAE and Qatar, where many Indians live. Recently, the Dubai government has banned the import and sale of paan and the like.[10]

According to traditional Ayurvedic medicine, chewing betel leaf is a remedy against bad breath (halitosis),[11] but it can possibly lead to oral cancer if taken with tobacco.

2.1. India

South Indian style Paan. By Charles Haynes from Sydney, Australia - dakshin paanUploaded by Ekabhishek, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10682568

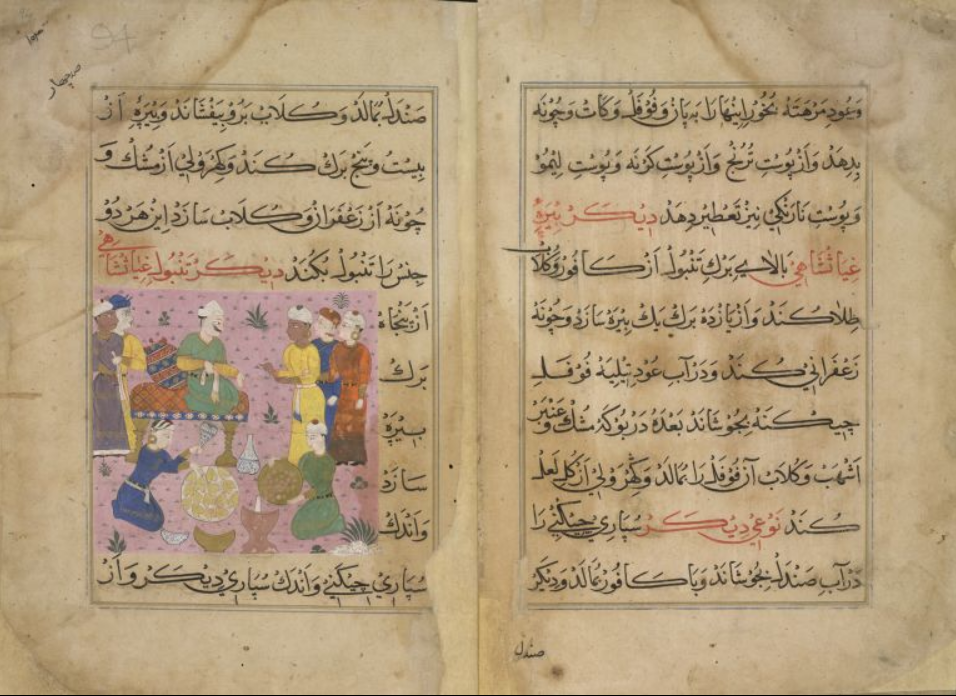

Ghiyath Shah, the Sultan of Mandu, India (r. 1469–1500), Malwa Sultanate, describes the elaborate way to prepare betel nut, folio from 16th century cookbook, medieval Indian Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=608917

Paan pot in Kolkata, India. By Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=56117276

Banarasi Maghai Paan. By Sanket Oswal - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=113392263

Paan (betel leaves) being served with silver foil at Sarnath near Varanasi, India. By ampersandyslexia - India, Day 15Uploaded by Ekabhishek, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10682034

In a 16th-century cookbook, Nimatnama-i Nasiruddin-Shahi, describes Ghiyas-ud-din Khalji, the Sultan of Mandu (r. 1469–1500), watches as tender betel leaves of the finest quality are spread out and rosewater is sprinkled on them, while saffron is also added. An elaborate betel chew or paan would contain fragrant spices and rose preserves with chopped areca nuts.

It is a tradition in South India and nearby regions to give two Betel leaves, areca nut (pieces or whole) and Coconut to the guests (both male and female) at any auspicious occasion. Even on a regular day, it is the tradition to give a married woman, who visits the house, two Betel leaves, areca nut and coconut or some fruits along with a string of threaded flowers. This is referred to as thamboolam.

Betel leaf used to make paan is produced in different parts of India. Some states that produce betel leaf for paan include West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh. In West Bengal, two types of betel leaves are produced. These are "Bangla Pata (Country Leaf)" and Mitha Pata (Sweet Leaf)". In West Bengal, Bangla pata is produced mainly in district of Dinajpur, Malda, Jalpaiguri, and Nadia. Mitha pata is produced in places such as Midnapur and South 24 Parganas.

The skilled paan maker is known as a paanwala in North India. In other parts, paanwalas are also known as panwaris or panwadis. At North India, there is a tradition to chew paan after Deepawali puja for blessings.

In the Indian state of Maharashtra, the paan culture is widely criticised due to the cleanliness problems created by people who spit in public places. In Mumbai, there have been attempts to put pictures of Hindu gods in places where people commonly tend to spit, in the hope that this would discourage spitting, but success has been limited. One of the great Marathi artists P L Deshpande wrote a comic story on the subject of paanwala (paan vendor), and performed a televised reading session on Doordarshan during the 1980s in his unique style.

Paan is losing its appeal to farmers because of falling demand. Consumers prefer chewing tobacco formulations such as gutka over paan. Higher costs, water scarcity and unpredictable weather have made betel gardens less lucrative.[12]

According to StraitsResearch, The India pan masala market is expected to reach US$10,365 million by 2026 at the CAGR of 10.4% during the forecast period 2019–2026. The India pan masala market is driven by significant switching of consumers from tobacco products to pan masala, aggressive advertising and convenient packaging, and Maharashtra State's revocation of the ban over pan masala products.[13]

Banarasi Pan

Banarasi Pan of Banaras (Varanasi) is widely famous among Indians and tourists visiting India.[14] [15][16]

2.2. Indonesia and Malaysia

A Javanese woman preparing betel leaf, c. 1880. By Kassian Cephas - Leiden University Library, KITLV, image 12084 Collection page Southeast Asian & Caribbean Images (KITLV), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=40513810

Balinese cerana or betel nut container. By Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11035700

Bersirih, nyirih or menginang is a Malayonesian tradition of chewing materials such as nut, betel, gambier, tobacco, clove and limestone.[17] Menginang tradition or chewing betel nut is widespread among Indonesian ethnic groups, especially among the Javanese, Balinese and Malay people; dating back to more than 3000 years.[18] Records of travelers from China showed that betel and areca had been consumed since the 2nd century BCE.[18]

In the Malay archipelago, the menginang or betel nut chewing has become a revered activity in local tradition; being a ceremoniously conducted gesture to honour guests. A complete and elaborate set of sirih pinang equipment is called tepak, puan, pekinangan or cerana. The set is usually made of wooden lacquerware, brass or silverwares; and it consists of the combol (containers), bekas sirih (leaf container), kacip (press-knife to cut areca nut), gobek (small pestle and mortar), and ketur (spit container).[17]

The Sirih Pinang has become a symbol of Malay culture,[19] with the Malay oral tradition having phrases such as "The betel opens the door to the home" or "the betel opens the door to the heart".[19] Menginang is used at many formal occasions such as marriages, births, deaths, and healings.[20] A number of Malay traditional dances—such as the South Sumatran Tanggai dance—are in fact describing the dancers bringing cerana or tepak sirih equipment, ceremoniously presenting an offering of betel nut to the revered guest.

2.3. Myanmar

Kwun-ya (ကွမ်းယာ [kóːn.jà]) is the word for paan in Myanmar, formerly Burma, where the most common configuration for chewing is a betel vine leaf (Piper betel), areca nut (from Areca catechu), slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) and some aroma, although many betel chewers also use tobacco.[21]

Betel chewing has very long tradition in Burma, having been practised since before the beginning of recorded history.[22] Until the 1960s, both men and women loved it and every household used to have a special lacquerware box for paan, called kun-it (ကွမ်းအစ်), which would be offered to any visitor together with cheroots to smoke and green tea to drink.[23] The leaves are kept inside the bottom of the box, which looks like a small hat box, but with a top tray for small tins, silver in well-to-do homes, of various other ingredients such as the betel nuts, slaked lime, cutch, anise seed and a nut cutter.[23] The sweet form (acho) is popular with the young, but grownups tend to prefer it with cardamom, cloves and tobacco. Spittoons, therefore, are still ubiquitous, and signs saying "No paan-spitting" are commonplace, as it makes a messy red splodge on floors and walls; many people display betel-stained teeth from the habit. Paan stalls and kiosks used to be run mainly by people of Indian origin in towns and cities. Smokers who want to kick the habit would also use betel nut to wean themselves off tobacco.

Taungoo in Lower Burma is where the best areca palms are grown indicated by the popular expression "like a betel lover taken to Taungoo".[24] Other parts of the country contribute to the best paan according to another saying "Tada-U for the leaves, Ngamyagyi for the tobacco, Taungoo for the nuts, Sagaing for the slaked lime, Pyay for the cutch". Kun, hsay, lahpet (paan, tobacco and pickled tea) are deemed essential items to offer monks and elders particularly in the old days. Young maidens traditionally carry ornamental betel boxes on a stand called kundaung and gilded flowers (pandaung) in a shinbyu (novitiation) procession. Burmese history also mentions an ancient custom of a condemned enemy asking for "a paan and a drink of water" before being executed.

An anecdotal government survey indicated that 40% of men and 20% of women in Myanmar chew betel.[25] An aggregate study of cancer registries (2002 to 2007) at the Yangon and Mandalay General Hospitals, the largest hospitals in the country, found that oral cancer was the 6th most common cancer among males, and 10th among females.[26] Of these oral carcinoma patients, 36% were regular betel quid chewers.[26] University of Dental Medicine, Yangon records from 1985 to 1988 showed that 58.6% of oral carcinoma patients were regular betel chewers.

Since the 1990s, betel chewing has been actively discouraged by successive governments, from the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) onward, on the grounds of health and tidiness.[22] In April 1995, the Yangon City Development Committee banned betel in Yangon (Rangoon), in anticipation of Visit Myanmar Year 1996, a massive effort to promote the country as a tourist destination.[27][28] Effective 29 July 2007, betel chewing, along with smoking, has been banned from the Shwedagon Pagoda, the country's most important religious site.[29] In 2010, the Ministry of Education's Department of Basic Education and Burma's Anti-Narcotics Task Force collaborated to prohibit betel shops from operating within 50 metres (160 ft) of any school.[30]

2.4. Pakistan

The consumption of paan has long been a very popular cultural tradition throughout Pakistan , especially in Muhajir households, where numerous paans were consumed throughout the day.[31] In general, though, paan is an occasional delicacy thoroughly enjoyed by many, and almost exclusively bought from street vendors instead of any preparations at home. Pakistan grows a large variety of betel leaf, specifically in the coastal areas of Sindh,[32] although paan is imported in large quantities from India , Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and, recently, Thailand. The paan business is famously handled and run by muhajir traders, who migrated from western India to Pakistan after the independence in 1947 (also cite pg 60, of Pakistan, By Samuel Willard Crompton, Charles F. Gritzner).

The culture of chewing paan has also spread in Punjab where a paan shop can be found in almost every street and market. In the famous Anarkali Bazar in Lahore a street called paan gali is dedicated for paan and its ingredients together with other Pakistani products.[33]

The rate of Oral cancer have grown substantially in Pakistan due to chewing of Paan.[34][35][36]

2.5. Vietnam

In Vietnam, the areca nut and the betel leaf are such important symbols of love and marriage that in Vietnamese the phrase "matters of betel and areca" (chuyện trầu cau) is synonymous with marriage. Areca nut chewing starts the talk between the groom's parents and the bride's parents about the young couple's marriage. Therefore, the leaves and juices are used ceremonially in Vietnamese weddings.[37]

2.6. Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, paan is chewed throughout the country by all classes and is an important element of Bangladeshi culture. It is the Bengali ‘chewing gum’, and usually for chewing, a few slices of the betel nut are wrapped in a betel leaf, almost always with sliced areca nuts and often with calcium hydroxide (slaked lime), and may include cinnamon, clove, cardamom, catechu (khoyer), grated coconut and other spices for extra flavouring. As it is chewed, the peppery taste is savoured, along with the warm feeling and alertness it gives (similar to drinking a fresh cup of coffee). Paan-shupari (shupari being Bengali for areca nut) is a veritable Bangladeshi archetypal imagery, employed in wide-ranging contexts. Prior to British rule, it was chewed without tobacco and it is still rarely chewed with tobacco. Betel leaves are arranged aesthetically on a decorated plate called paandani and it is offered to the elderly people, particularly women, when they engage in leisure time gossip with their friends and relatives. During the zamindari age, paan preparation and the style of garnishing it on a plate (paandani) was indeed a recognised folk art.

In Bangladesh paan is traditionally chewed not only as a habit but also as an item of rituals, etiquette and manners. On formal occasions offering paan symbolized the time for departure. In festivals and dinners, in pujas and punyas paan is an indispensable item. Hindus make use of paans as offerings in worship.

Dhakai Khilipan, a ready pack of betel leaf processed in Dhaka is famous in the sub-continent. Old Dhakaites have a rich heritage of creating the best khili paan with many complex, colourful, aromatic and mouth-watering ingredients. Although 'paan' has been a staple Bengali custom for ages, a number of high-end stores with premium quality paan has become available in recent times. Paan Supari is perhaps the first such brand, which offers a wide range of khili paan. They also offer a khili paan for diabetic patients called the "paan afsana".

The sweet paan of the Khasi tribe is famous for its special quality. Paan is also used in Hindu puja and wedding festivals and to visit relatives. It has become a ritual, tradition and culture of Bangladeshi society. Adult women gather with paandani[38] along with friends and relatives in leisure time.

Total cultivated area under the crop in Bangladesh is about 14,175 ha and the total annual production is about 72,500 tons. The average yield per acre is 2.27 tons. There are usually three crops during the twelve months and they are locally called by the name of the respective months in which they are harvested. Paan leaf is usually plucked in Kartik, Phalgun and Ashad. The Kartik paan is considered by consumers to be the best and Ashad paan the worst. When plucking, it is a rule to leave at least sixteen leaves on the vine.[38]

Different varieties of betel leaf are grown and the quality differs in shape, bleaching quality, softness, pungency and aroma of leaf. Tamakh paan, a betel leaf blended with tobacco and spices. Supari paan, another variety of white leaf, Mitha paan, a sweet variety, and Sanchi paan are common varieties of betel leaves. Almost every paan-producing district has its own special variety of betel leaf of which consumers are well acquainted. In the past, the best quality of elegant camphor-scented betel leaf named Kafuri paan was produced in the Sonargaon area of Narayangonj district. It was exported to Calcutta and Middle Eastern countries. The next best is the Sanchi paan grown in Chittagong hill tracts. This variety is not very popular among Bangali people. It is exported to Pakistan for the consumers of Karachi. The commoner varieties are called Desi, Bangla, Bhatial, Dhaldoga, Ghas paan. Bangla paan, is also known as Mitha paan, Jhal paan or paan of Rajshahi. At present, this variety is becoming extinct, due to emergence of more profitable and lucrative fast-growing varieties of paan crops. Normally, betel leaves are consumed with chun, seed cinnamon, cardamoms and other flavored elements.[38]

2.7. Taiwan

In Taiwan betel quid is sold from roadside kiosks, often by the so-called betelnut beauties (simplified Chinese: 槟榔西施; traditional Chinese: 檳榔西施; pinyin: bīnláng xīshī; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: pin-nn̂g se-si) — scantily-clad girls selling a quid preparation of betel leaf, betel nuts, tobacco and lime. It is a controversial business, with critics questioning entrapment, exploitation, health, class and culture.[39]

Betelnut Beauty kiosk in Taiwan. By Klingone86 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11077421

3. Effects on Health

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) accept the scientific evidence that chewing betel quids and areca nut is carcinogenic to humans.[40][41][42][43] The main carcinogenic factor is believed to be areca nut. A recent study found that areca-nut paan with and without tobacco increased oral cancer risk by 9.9 and 8.4 times, respectively.[44]

In one study (c. 1985),[45] scientists linked malignant tumours to the site of skin or subcutaneous administration of aqueous extracts of paan in mice. In hamsters, forestomach carcinomas occurred after painting the cheek-pouch mucosa with aqueous extracts or implantation of a wax pellet containing powdered paan with tobacco into the cheek pouch; carcinomas occurred in the cheek pouch following implantation of the wax pellets. In human populations, they reported observing elevated frequencies of micronucleated cells in buccal mucosa of people who chew betel quid in the Philippines and India. The scientists also found that the proportion of micronucleated exfoliated cells is related to the site within the oral cavity where the paan is kept habitually and to the number of betel quids chewed per day. In related studies,[45] the scientists reported that oral leukoplakia shows a strong association with habits of paan chewing in India. Some follow-up studies have shown malignant transformation of a proportion of leukoplakias. Oral submucous fibrosis and lichen planus, which are generally accepted to be precancerous conditions, appear to be related to the habit of chewing paan.

In a study conducted in Taiwan,[46] scientists reported the extent of cancer risks of betel quid (paan) chewing beyond oral cancer, even when tobacco was absent. In addition to oral cancer, significant increases were seen among chewers for cancer of the oesophagus, liver, pancreas, larynx, lung, and all cancer. Chewing and smoking, as combined by most betel chewers, interacted synergistically and was responsible for half of all cancer deaths in this group. Chewing betel leaf quid and smoking, the scientists claimed, shortened the life span by nearly six years.

A Lancet Oncology publication claims that paan masala may cause tumours in different parts of the body and not just the oral cavity as previously thought.[47]

In a study conducted in Sri Lanka,[48] scientists found high prevalence of oral potentially malignant disorders in rural Sri Lankan populations. After screening for various causes, the scientists reported paan chewing to be the major risk factor, with or without tobacco.

In October 2009, 30 scientists from 10 countries met at the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a World Health Organization sponsored group, to reassess the carcinogenicity of various agents including areca nut, a common additive in paan. They reported there is sufficient evidence that paan chewing, even without tobacco, leads to tumours in the oral cavity and oesophagus, and that paan with added tobacco is a carcinogen to the oral cavity, pharynx and oesophagus.[49]

Effects of chewing paan during pregnancy

Scientific teams from Taiwan, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea have reported that women who chew areca nut formulations, such as paan, during pregnancy significantly increase adverse outcomes for the baby. The effects were similar to those reported for women who consume alcohol or tobacco during pregnancy. Lower birth weights, reduced birth length and early term were found to be significantly higher.[50][51]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Chemistry:Paan

References

- Zumbroich, Thomas J. (2007–2008). "The origin and diffusion of betel chewing: a synthesis of evidence from South Asia, Southeast Asia and beyond". eJournal of Indian Medicine 1: 87–140. https://ugp.rug.nl/eJIM/article/download/24712/22162.

- Cunningham, A.B.; Ingram, W.; DaosKadati, W.; Howe, J.; Sujatmoko, S.; Refli, R.; Liem, J.V.; Tari, A. et al. (2011). Hidden economies, future options: trade in non-timber forest products in eastern Indonesia. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR). ISBN 9781921738685. https://www.aciar.gov.au/file/75681/download?token=Z3LzN2aP.

- Heathcote, Gary M.; Diego, Vincent P.; Ishida, Hajime; Sava, Vincent J. (2012). "An osteobiography of a remarkable protohistoric Chamorro man from Taga, Tinian". Micronesica 43 (2): 131–213.

- Lebot, V.; Lèvesque, J. (1989). "The Origin and Distribution of Kava (Piper methysticum Forst. F., Piperaceae): A Phytochemical Approach". Allertonia 5 (2): 223–281.

- Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen (2013). "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress". Oceanic Linguistics 52 (2): 493–523. doi:10.1353/ol.2013.0016. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265931196.

- Mahdi, Waruno (1999). "The Dispersal of Austronesian boat forms in the Indian Ocean". in Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew. Archaeology and Language III: Artefacts languages, and texts. One World Archaeology. 34. Routledge. pp. 144–179. ISBN 978-0415100540.

- "Paan spitting clampdown launched by Brent Council". BBC News. 23 March 2010. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/england/london/8580076.stm.

- "Fines may be effective in stopping people from spitting on the streets". DNA India. 25 March 2010. http://www.dnaindia.com/speakup/report_fines-may-be-effective-in-stopping-poeple-from-spitting-on-teh-streets_1363437.

- Archaeological evidence from Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. http://www.epistola.com/sfowler/scholar/scholar-betel.html

- Sengupta, Joy (9 October 2008). "Selling Betel Leaves? You'll be Deported Immediately". KhaleejTimes.com. http://khaleejtimes.com/DisplayArticleNew.asp?section=theuae&xfile=data/theuae/2008/october/theuae_october191.xml.

- Pattnaik, Naveen (1993). The Garden of Life: An Introduction to the Healing Plants of India. Doubleday. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-385-42469-1. https://archive.org/details/gardenoflifeintr00patn/page/70.

- Mahapatra (21 March 2011). "Paan loses flavour". http://www.downtoearth.org.in/node/33175.

- "Indian Pan Masala Market Share Analysis". Industry News Wire. https://industrynewswire.us/what-are-the-key-challenges-to-india-pan-masala-market-growth/136971/.

- "Love Banarasi Paan? Find Out About All Kinds Of Paan Available in Banaras" (in en). https://food.ndtv.com/food-drinks/ever-heard-of-banarasi-paan-find-how-s-it-different-from-regular-paan-2066169.

- "Stuff of legend" (in en). https://www.financialexpress.com/lifestyle/stuff-of-legend/56119/.

- "The Banarasi Food Twist" (in en). http://indianculture.gov.in/food-and-culture/street-food/banarasi-food-twist.

- "Tradisi Bersirih dan Nilai Budayanya" (in ms). MelayuOnline.com. http://melayuonline.com/ind/culture/dig/1703.

- "Menginang, Cikal Bakal Tradisi Kretek Nusantara". Kompasiana.com. http://kompasiana.com/post/read/645837/2/menginang-cikal-bakal-tradisi-kretek-nusantara.html.

- Azhari, Evada. Menginang adalah. https://www.academia.edu/6455612. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- "Filosofi Menginang (Makan Pinang)". Jakarta.Kompasiana.com. http://jakarta.kompasiana.com/sosial-budaya/2012/12/04/filosofi-me-nginang-makan-pinang--513407.html.

- Betel-quid and Areca-nut Chewing and Some Areca-Nut Derived Nitrosamines. 85. World Health Organization. 2004. p. 68. ISBN 978-92-832-1285-0.

- Seekins, Donald M. (2006). Historical Dictionary of Burma (Myanmar). Scarecrow Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8108-5476-5. https://archive.org/details/historicaldictio00seek.

- Forbes, Charles James (1878). British Burma and its people. J. Murray. https://archive.org/details/britishburmaand01forbgoog.

- Reid, Robert; Michael Grosberg (2005). Myanmar (Burma). Lonely Planet. p. 290. ISBN 978-1-74059-695-4.

- Khin Myat (2 July 2007). "Betel chewers face health dangers". Myanmar Times. http://mmtimes.com/no373/n006.htm.

- Oo, Htun Naing; Myint, Yi Yi; Maung, Chan Nyein; Oo, Phyu Sin; Cheng, Jun; Maruyama, Satoshi; Yamazaki, Manabu; Yagi, Minoru et al. (2011). "Oral cancer in Myanmar: A preliminary survey based on hospital-based cancer registries". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 40 (1): 20–6. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00938.x. PMID 20819123. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1600-0714.2010.00938.x

- Köllner, Helmut; Axel Bruns (1998). Myanmar (Burma). Hunter Publishing. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-3-88618-415-6.

- Shenon, Philip (14 June 1995). "Yangon Journal; Burmese Generals Ask Less Spit, More Polish". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1995/06/14/world/yangon-journal-burmese-generals-ask-less-spit-more-polish.html.

- Ye Kaung Myint Maung (6 August 2006). "Smoking banned at Shwedagon". Myanmar Times. http://www.mmtimes.com/no378/n010.htm.

- Nay Nwe Moe Aung (12 July 2010). "No more betel shops near schools". Myanmar Times. http://www.mmtimes.com/2010/news/531/news007.html.

- Meetha or saada, Karachi's love for paan is unmatched https://www.dawn.com/news/1299840

- Betel-leaf farming in coastal area https://www.dawn.com/news/33381

- Mir, Amir (3 December 2005). "Paan Gali, Lahore's very own Chandni Chowk". DNA. http://www.dnaindia.com/world/report_paan-gali-lahore-s-very-own-chandni-chowk_1000393.

- Public health: 'Paan, supari, gukta leading causes of oral cancer' https://www.siasat.pk/forum/showthread.php?228542-40-of-cancer-patients-in-Pakistan-have-oral-cancer-mostly-caused-by-Paan-Supari-and-Gutka

- Merchant, AT; Pitiphat, W (2015). "Total, direct, and indirect effects of paan on oral cancer". Cancer Causes Control 26 (3): 487–91. doi:10.1007/s10552-014-0516-x. PMID 25542140. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4334743

- Niaz, K; Maqbool, F; Khan, F; Bahadar, H; Ismail Hassan, F; Abdollahi, M (2017). "Smokeless tobacco (paan and gutkha) consumption, prevalence, and contribution to oral cancer". Epidemiol Health 39: e2017009. doi:10.4178/epih.e2017009. PMID 28292008. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5543298

- "Vietnamese Legend: Story of the betel leaf and the areca nut". http://www.vietspring.org/legend/traucau.html.

- Karim, ASM Enayet (2012). "Pan1". in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A.. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Pan1.

- Mark Magnier (22 January 2009). "Taiwan's 'betel nut beauties' drum up business, and debate". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2009/jan/22/world/fg-betel-beauty22.

- IARC Working Group. Betel-quid and areca-nut chewing and some areca-nut-derived Nitrosamines. The World Health Organization. ISBN 9789283215851. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol85/mono85.pdf.

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: the MPOWER package. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2008. ISBN 978-92-4-159628-2. https://www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/mpower_report_full_2008.pdf.

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Trivedy, C; Peters, TJ (2002). "Areca nut use: An independent risk factor for oral cancer". BMJ 324 (7341): 799–800. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7341.799. PMID 11934759. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1122751

- 3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 1515978. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F1097-0142%2819920901%2970%3A5%3C1017%3A%3AAID-CNCR2820700502%3E3.0.CO%3B2-%23" id="ref_43">Dave, Bhavana J.; Trivedi, Amit H.; Adhvatyu, Siddharth G. (1992). "Role of areca nut consumption in the cause of oral cancers. A cytogenetic assessment". Cancer 70 (5): 1017–23. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19920901)70:5<1017::AID-CNCR2820700502>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 1515978. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F1097-0142%2819920901%2970%3A5%3C1017%3A%3AAID-CNCR2820700502%3E3.0.CO%3B2-%23

- 3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 10728606. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F%28SICI%291097-0215%2820000401%2986%3A1%3C128%3A%3AAID-IJC20%3E3.0.CO%3B2-M" id="ref_44">Merchant, Anwar; Husain, Syed S. M.; Hosain, Mervyn; Fikree, Fariyal F.; Pitiphat, Waranuch; Siddiqui, Amna Rehana; Hayder, Syed J.; Haider, Syed M. et al. (2000). "Paan without tobacco: An independent risk factor for oral cancer". International Journal of Cancer 86 (1): 128–31. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000401)86:1<128::AID-IJC20>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 10728606. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2F%28SICI%291097-0215%2820000401%2986%3A1%3C128%3A%3AAID-IJC20%3E3.0.CO%3B2-M

- The World Health Organization IARC Expert Group. "IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of the Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans, Vol. 37, Tobacco Habits Other than Smoking; Betel-Quid and Areca-nut Chewing; and Some Related Nitrosamines, Lyon". IARCPress. http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol37/volume37.pdf.

- Wen, Chi Pang; Tsai, Min Kuang; Chung, Wen Shen Isabella; Hsu, Hui Ling; Chang, Yen Chen; Chan, Hui Ting; Chiang, Po Huang; Cheng, Ting-Yuan David et al. (2010). "Cancer risks from betel quid chewing beyond oral cancer: A multiple-site carcinogen when acting with smoking". Cancer Causes & Control 21 (9): 1427–35. doi:10.1007/s10552-010-9570-1. PMID 20458529. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs10552-010-9570-1

- Sharma, Dinesh C (2001). "Indian betel quid more carcinogenic than anticipated". The Lancet Oncology 2 (8): 464. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(01)00444-2. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS1470-2045%2801%2900444-2

- Amarasinghe, Hemantha K.; Usgodaarachchi, Udaya S.; Johnson, Newell W.; Lalloo, Ratilal; Warnakulasuriya, Saman (2010). "Betel-quid chewing with or without tobacco is a major risk factor for oral potentially malignant disorders in Sri Lanka: A case-control study". Oral Oncology 46 (4): 297–301. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.017. PMID 20189448. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.oraloncology.2010.01.017

- Secretan, Béatrice; Straif, Kurt; Baan, Robert; Grosse, Yann; El Ghissassi, Fatiha; Bouvard, Véronique; Benbrahim-Tallaa, Lamia; Guha, Neela et al. (2009). "A review of human carcinogens—Part E: Tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, coal smoke, and salted fish". The Lancet Oncology 10 (11): 1033–4. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70326-2. PMID 19891056. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS1470-2045%2809%2970326-2

- Senn, M.; Baiwog, F.; Winmai, J.; Mueller, I.; Rogerson, S.; Senn, N. (2009). "Betel nut chewing during pregnancy, Madang province, Papua New Guinea". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 105 (1–2): 126–31. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.021. PMID 19665325. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.drugalcdep.2009.06.021

- Yang, Mei-Sang; Lee, Chien-Hung; Chang, Shun-Jen; Chung, Tieh-Chi; Tsai, Eing-Mei; Ko, Allen Min-Jen; Ko, Ying-Chin (2008). "The effect of maternal betel quid exposure during pregnancy on adverse birth outcomes among aborigines in Taiwan". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 95 (1–2): 134–9. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.003. PMID 18282667. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.drugalcdep.2008.01.003