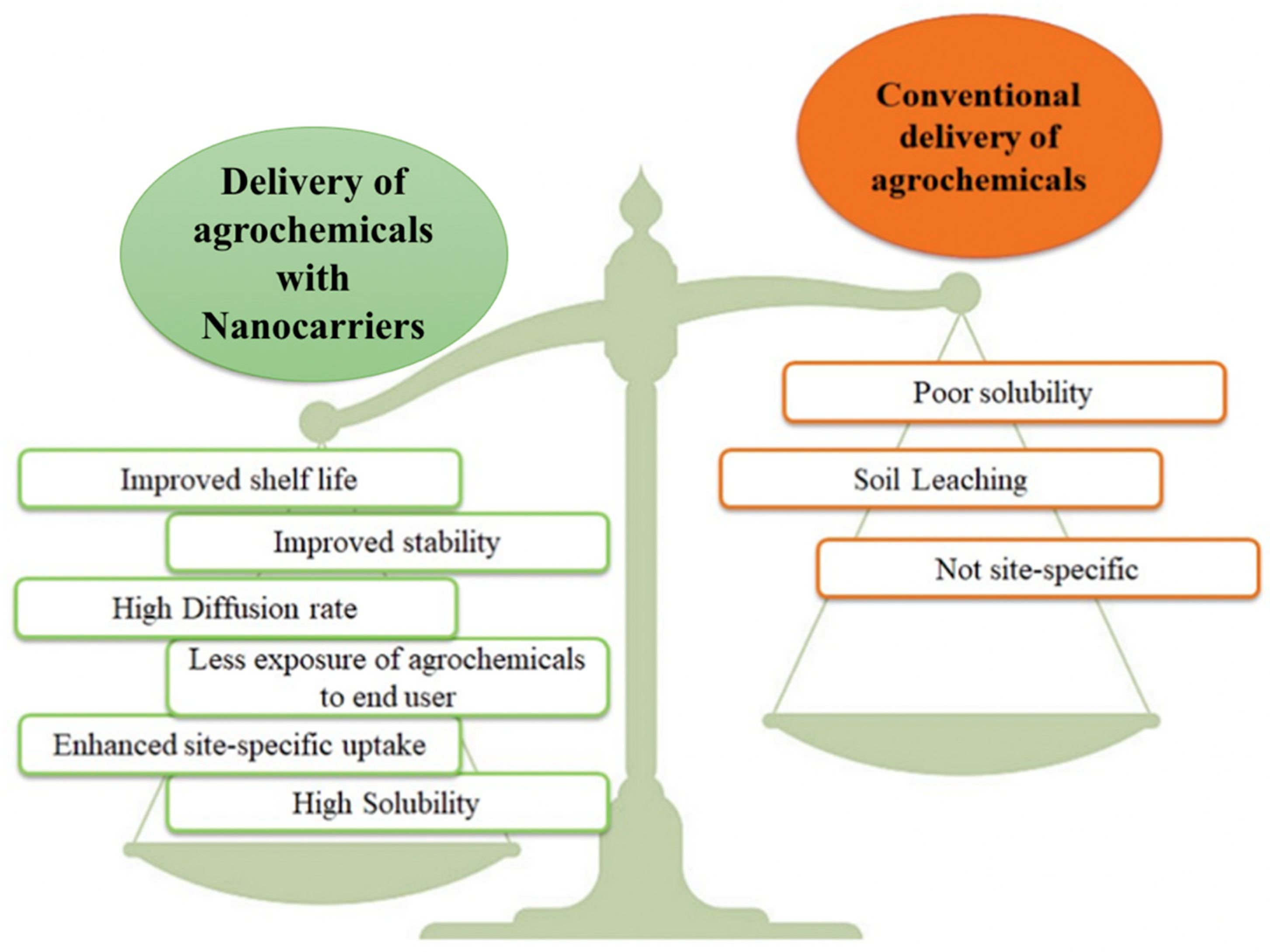

The world is facing immense challenges in terms of food security, due to the combined impacts of the ever-increasing population and the adversity of climate change. In an attempt to counteract these factors, smart nutrient delivery systems, including nano-fertilizers, additives, and material coatings, have been introduced to increase food productivity to meet the growing food demand. Use of nanocarriers in agro-practices for sustainable farming contributes to achieving up to 75% nutrient delivery for a prolonged period to maintain nutrient availability in soil for plants in adverse soil conditions.

- engineered nano-zeolites

- controlled-release fertilizers

- toxic effects

1. Introduction

2. Smart Nutrient Delivery: Nano-Fertilizers and Their Mode of Action

- i.

-

Nanoscale fertilizers (nanoparticles of silica, iron, etc., which contain nutrients);

- ii.

-

Nanoscale additives (established fertilizers with nanoscale additives);

- iii.

-

Nanoscale coatings (fertilizers coated with nanoscale materials).

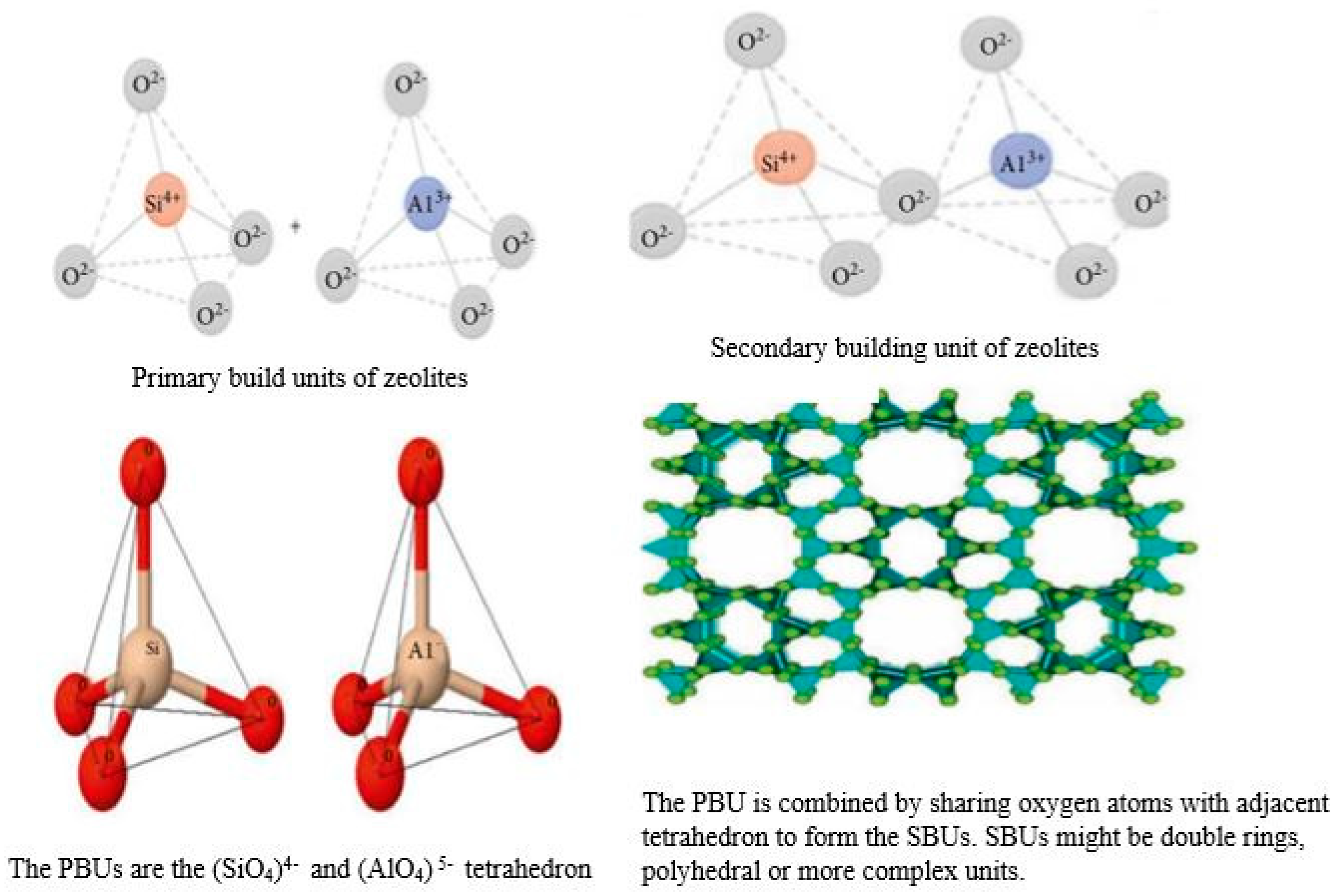

3. Zeolites: Potential Candidates for Modern Agricultural Practices

-

Zeolite with a low Si-Al ratio (1–1.5): zeolite 4A, X, UZM-4 and UZM-5, etc.

-

Zeolite with intermediate Si-Al ratio (2–5): mordenite, LTA type, etc.

-

Zeolite with a high Si-Al ratio (10–several thousand): ZSM-5, ZSM-12, etc.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/applnano3030013

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision. Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2013. Available online: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:World+Population+Prospects+The+2012+Revision#1 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Connor, D.J.; Loomis, R.S.; Cassman, K.G. Connor, Crop Ecology: Productivity and Management in Agricultural Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011.

- Prashar, P.; Shah, S. Impact of Fertilizers and Pesticides on Soil Microflora in Agriculture. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 331–361.

- Rai, M.; Ribeiro, C.; Mattoso, L.; Duran, N. (Eds.) Nanotechnologies in Food and Agriculture; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; 347p.

- Chugh, G.; Siddique, K.; Solaiman, Z. Nanobiotechnology for Agriculture: Smart Technology for Combating Nutrient Deficiencies with Nanotoxicity Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1781.

- Acharya, A.; Pal, P.K. Agriculture nanotechnology: Translating research outcome to field applications by influencing environmental sustainability. NanoImpact 2020, 19, 100232.

- Tzia, C.; Zorpas, A.A. Zeolites in Food Processing Industries. In Handbook of Natural Zeolites; Bentham Science Publishers: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2012; pp. 601–651.

- Król, M. Natural vs. Synthetic Zeolites. Crystals 2020, 10, 622.

- Bernardi, A.C.D.C.; Polidoro, J.C.; Monte, M.B.D.M.; Pereira, E.I.; de Oliveira, C.R.; Ramesh, K. Enhancing Nutrient Use Efficiency Using Zeolites Minerals—A Review. Adv. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2016, 06, 295–304.

- Williams, K.A.; Nelson, P.V. Using Precharged Zeolite as a Source of Potassium and Phosphate in a Soilless Container Medium during Potted Chrysanthemum Production. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1997, 122, 703–708.

- Aghaalikhani, M.; Gholamhoseini, M.; Dolatabadian, A.; Khodaei-Joghan, A.; Asilan, K.S. Zeolite influences on nitrate leaching, nitrogen-use efficiency, yield and yield components of canola in sandy soil. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2012, 58, 1149–1169.

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. Use of surfactant-modified zeolite to carry and slowly release sulfate. Desalin. Water Treat. 2010, 21, 73–78.

- Polat, E.; Karaca, M.; Demir, H.; Onus, A.N. Use of natural zeolite (clinoptilolite) in agriculture. J. Fruit Ornam. Plant Res. 2004, 12, 183–189.

- Jarosz, R.; Szerement, J.; Gondek, K.; Mierzwa-Hersztek, M. The use of zeolites as an addition to fertilisers—A review. Catena 2022, 213, 106125.

- Yuvaraj, M.; Subramanian, K.S. Novel Slow Release Nanocomposite Fertilizers. In Nanotechnology and the Environment; IntechOpen: Vienna, Austria, 2020.

- Elizabath, A.; Rme, S.I. Application of Nanotechnology in Agriculture. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2019, 7, 131–139.

- Sheta, A.; Falatah, A.; Al-Sewailem, M.; Khaled, E.; Sallam, A. Sorption characteristics of zinc and iron by natural zeolite and bentonite. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2003, 61, 127–136.

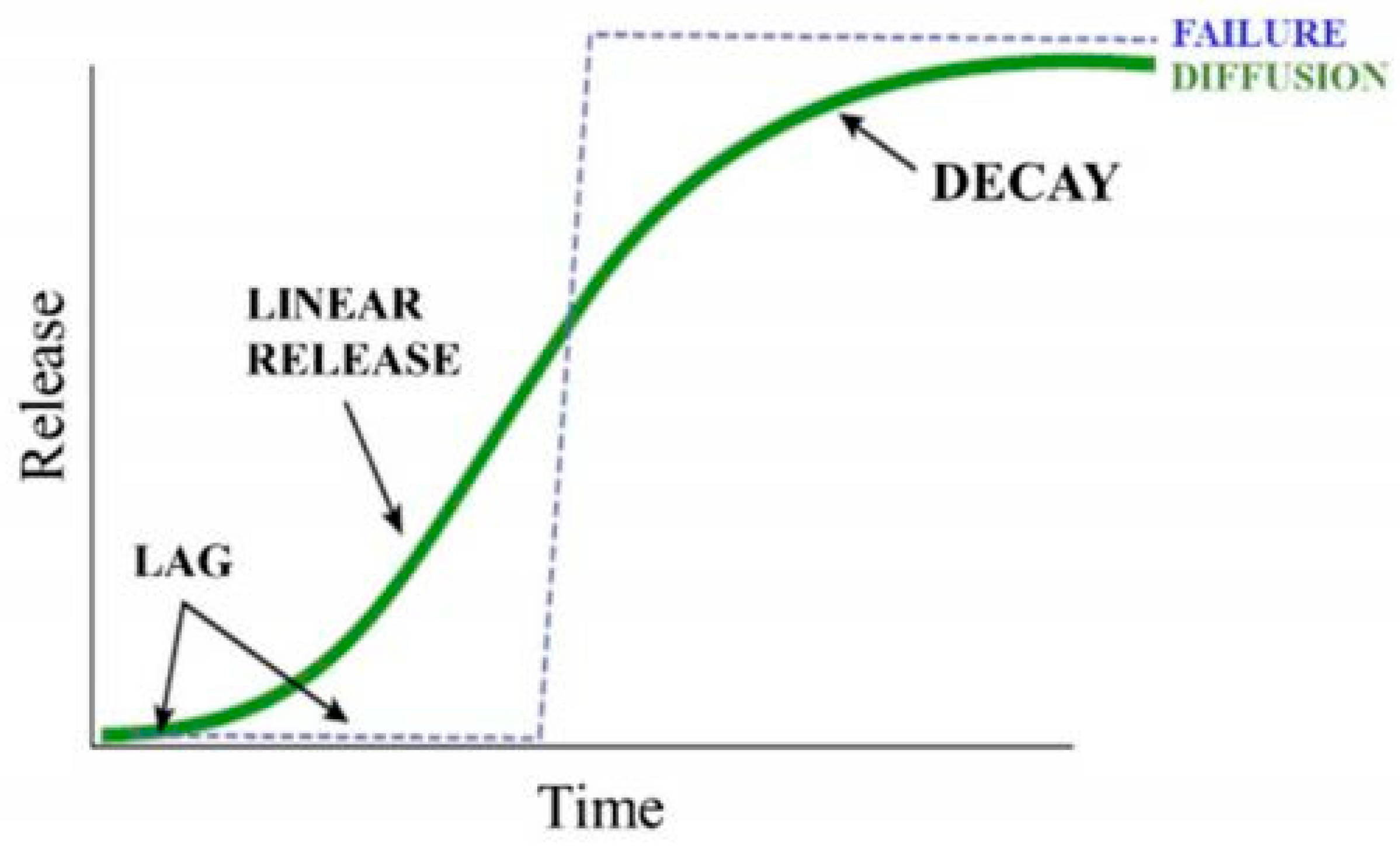

- Shaviv, A.; Raban, S.; Zaidel, E. Modeling Controlled Nutrient Release from Polymer Coated Fertilizers: Diffusion Release from Single Granules. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 2251–2256.

- Sempeho, S.I.; Kim, H.T.; Mubofu, E.; Hilonga, A. Meticulous Overview on the Controlled Release Fertilizers. Adv. Chem. 2014, 2014, 363071.

- Irfan, S.A.; Razali, R.; KuShaari, K.; Mansor, N.; Azeem, B.; Versypt, A.N.F. A review of mathematical modeling and simulation of controlled-release fertilizers. J. Control. Release 2018, 271, 45–54.

- Trenkel, M.E. Slow-and Controlled-Release and Stabilized Fertilizers: An Option for Enhancing Nutrient Use Effiiency in Agriculture; IFA (International Fertilizer Industry Association): Paris, France, 2010.

- Iskander, A.; Khald, E.; Sheta, A.E.-A. Zinc and manganese sorption behavior by natural zeolite and bentonite. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2011, 56, 43–48.

- Bacakova, L.; Vandrovcova, M.; Kopova, I.; Jirka, I. Applications of zeolites in biotechnology and medicine—A review. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 974–989.

- Mintova, S. Nanosized Molecular Sieves. Collect. Czechoslov. Chem. Commun. 2003, 68, 2032–2054.

- Kalló, D. Applications of Natural Zeolites in Water and Wastewater Treatment. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2001, 45, 519–550.

- Jiménez-Reyes, M.; Almazán-Sánchez, P.; Solache-Ríos, M. Radioactive waste treatments by using zeolites. A short review. J. Environ. Radioact. 2021, 233, 106610.

- Corma, A.; Iborra, S.; Velty, A. Chemical Routes for the Transformation of Biomass into Chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 2411–2502.

- Sangeetha, C.; Baskar, P. Zeolite and its potential uses in agriculture: A critical review. Agric. Rev. 2016, 37.

- Derbe, T.; Temesgen, S.; Bitew, M. A Short Review on Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Zeolites. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6637898.

- Bhattacharyya, T.; Chandran, P.; Ray, S.K.; Pal, D.K.; Mandal, C.; Mandal, D.K. Distribution of Zeolitic Soils in India. Curr. Sci. 2015, 109, 1305.

- Sekhon, B.S.; Sangha, M.K. Detergents—Zeolites and enzymes excel cleaning power. Resonance 2004, 9, 35–45.

- Li, R.; Chong, S.; Altaf, N.; Gao, Y.; Louis, B.; Wang, Q. Synthesis of ZSM-5/Siliceous Zeolite Composites for Improvement of Hydrophobic Adsorption of Volatile Organic Compounds. Front. Chem. 2019, 7, 505.

- Ming, D.W.; Allen, E.R. Use of Natural Zeolites in Agronomy, Horticulture and Environmental Soil Remediation. Rev. Miner. Geochem. 2001, 45, 619–654.

- Ramesh, K.; Reddy, D.D. Zeolites and Their Potential Uses in Agriculture. Adv. Agron. 2011, 113, 219–241.

- Leggo, P.J. An investigation of plant growth in an organo-zeolitic substrate and its ecological significance. Plant Soil 2000, 219, 135–146.

- Valente, S.; Burriesci, N.; Cavallaro, S.; Galvagno, S.; Zipelli, C. Utilization of zeolites as soil conditioner in tomato-growing. Zeolites 1982, 2, 271–274.

- Campbell, L.S.; Davies, B.E. Experimental Investigation of Plant Uptake of Caesium from Soils Amended with Clinoptilolite and Calcium Carbonate; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Volume 189, pp. 65–74. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42947951 (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Al Dwairi, R.A.; Aiman, A. Recent Patents of Natural Zeolites Applications in Environment, Agriculture and Pharmaceutical Industry. Recent Patents Chem. Eng. 2012, 5, 20–27.

- Sun, C.-Y.; Qin, C.; Wang, X.-L.; Yang, G.-S.; Shao, K.-Z.; Lan, Y.-Q.; Su, Z.-M.; Huang, P.; Wang, C.-G.; Wang, E.-B. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 as efficient pH-sensitive drug delivery vehicle. Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 6906–6909.

- Mahmodi, G.; Zarintaj, P.; Taghizadeh, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Manouchehri, S.; Dangwal, S.; Ronte, A.; Ganjali, M.R.; Ramsey, J.D.; Kim, S.-J.; et al. From microporous to mesoporous mineral frameworks: An alliance between zeolite and chitosan. Carbohydr. Res. 2020, 489, 107930.

- Serati-Nouri, H.; Jafari, A.; Roshangar, L.; Dadashpour, M.; Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi, Y.; Zarghami, N. Biomedical applications of zeolite-based materials: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 116, 111225.

- Rahmani, S.; Azizi, S.N.; Asemi, N. Application of Synthetic Nanozeolite Sodalite in Drug Delivery. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 2016, 5, 55–58. Available online: http://www.icpjonline.com/documents/Vol5Issue6/02.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Sotoudeh, S.; Barati, A.; Davarnejad, R.; Farahani, M.A. Antibiotic release process from hydrogel nano zeolite composites. Middle East J. Sci. Res. 2012, 12, 392–396.

- Qotob, M.A.; Nasef, M.A.; Elhakim, H.K.; Shaker, O.G.; Abdelhamid, I.A. Revisiting of chemical fertilizers by using suitable plant growth regulators and nano fertilizer. GSJ 2020, 8, 1896–1907.

- Khaleque, A.; Alam, M.; Hoque, M.; Mondal, S.; Bin Haider, J.; Xu, B.; Johir, M.; Karmakar, A.K.; Zhou, J.; Ahmed, M.B.; et al. Zeolite synthesis from low-cost materials and environmental applications: A review. Environ. Adv. 2020, 2, 100019.

- Fu, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, Z.; Shen, J.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Ding, T.; Xu, L.; Lee, S.S. Ammonium removal using a calcined natural zeolite modified with sodium nitrate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122481.

- Cieśla, J.; Franus, W.; Franus, M.; Kedziora, K.; Gluszczyk, J.; Szerement, J.; Jozefaciuk, G. Environmental-Friendly Modifications of Zeolite to Increase Its Sorption and Anion Exchange Properties, Physicochemical Studies of the Modified Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 3213.

- Ren, H.; Jiang, J.; Wu, D.; Gao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Luo, C. Selective Adsorption of Pb(II) and Cr(VI) by Surfactant-Modified and Unmodified Natural Zeolites: A Comparative Study on Kinetics, Equilibrium, and Mechanism. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 101.

- Qureshi, A.; Singh, D.; Dwivedi, S. Nano-fertilizers: A Novel Way for Enhancing Nutrient Use Efficiency and Crop Productivity. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 3325–3335.

- Mahabadi, A.A.; Hajabbasi, M.; Khademi, H.; Kazemian, H. Soil cadmium stabilization using an Iranian natural zeolite. Geoderma 2007, 137, 388–393.

- Bernardi, A.C.D.C.; Oliviera, P.P.A.; Monte, M.B.D.M.; Souza-Barros, F. Brazilian sedimentary zeolite use in agriculture. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 167, 16–21.

- Groen, J.C.; Jansen, J.C.; Moulijn, A.J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, J. Optimal Aluminum-Assisted Mesoporosity Development in MFI Zeolites by Desilication. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 13062–13065.

- Moritani, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Andry, H.; Inoue, M.; Yuya, A.; Kaneuchi, T. Effectiveness of artificial zeolite amendment in improving the physicochemical properties of saline-sodic soils characterised by different clay mineralogies. Soil Res. 2010, 48, 470–479.

- Gholizadeh-Sarabi, S.; Sepaskhah, A.R. Effect of zeolite and saline water application on saturated hydraulic conductivity and infiltration in different soil textures. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2013, 59, 753–764.

- Mintova, S.; Gilson, J.-P.; Valtchev, V. Advances in nanosized zeolites. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 6693–6703.