Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Genetics & Heredity

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is an inherited disease related to an alteration in angiogenesis, manifesting as cutaneous telangiectasias and epistaxis. As complications, it presents vascular malformations in organs such as the lung, liver, digestive tract, and brain.

- hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasias

- arteriovenous malformations

- angiogenesis

1. History and Epidemiology

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Rendu–Osler–Weber Syndrome, is a rare disease characterized by multisystemic vascular dysplasia [1].

Although it was first described by the British pathologist Henry Gawen Sutton in 1864 [2], it would be another 32 years before it was first differentiated from hemophilia by the French physician Henri Jules Louis Marie Rendu [3].

This disease can present a wide variability of clinical manifestations and can differ markedly even among members of the same family. Its prevalence is, according to recent estimates, 1 case per 5000 inhabitants [4]. However, there are geographical areas where frequencies are higher, such as the Dutch Antilles, the island of Funen, Denmark, the French region of Ain, Vermont (USA), Newcastle (United Kingdom), and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (Spain) [5].

This disease is caused, in approximately 90% of cases, by a heterozygous mutation of the endoglin gene (ENG) or the activin-like receptor kinase 1, called ALK1 (also known as ACVRL1), characterized by an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. In addition to these two genes, alteration of SMAD4 has been identified in a subset of patients with HHT and juvenile polyposis (approximately 2% of cases), a condition termed PJ-HHT syndrome, in which juvenile polyps and anemia are the predominant clinical features. Disruption of the ENG gene, located on chromosome 9 (9q3.3-q3.4), causes HHT type 1 (HHT1), while mutation of the ACVRL1 gene, located on chromosome 12 (12q13), causes HHT type 2 (HHT2) [5]. Table 1 shows the main genes responsible for HHT, including all the phenotypes described to date [6,7]. Other less frequently affected genes have been described such as GDF2 and RASA-1. There is a close overlap between capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation (CM–AVM) syndrome and HHT, both related to the RASA-1 gene mutation but expressing different phenotypes [7,8,9,10].

| Gen | Affected Protein | Location | Phenotype | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENG | Endoglin | 9q34.11 | HHT1 | 39–59% |

| ACVRL1 | ALK1 | 12q13.13 | HHT2 | 25–57% |

| MADH4 | Smad4 | 18q21.1 | HHT-juvenile polyposis syndrome | 1–2% |

| GDF2 | BMP9 | 10q11.22 | HHT-like | <1% |

| RASA-1 | p120-RasGAP | 5q14.3 | RASA-1 related disorders (CM-AVM) | Unknown |

HHT, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia; GDF, growth differentiation factor; p120-RasGAP, P120-Ras GTPase activating protein; CM–AVM, capillary malformation–arteriovenous malformation syndrome.

2. Pathophysiology

2.1. Regulation of Angiogenesis

The relationship between the endothelium and affected genes in HHT is based on the positive regulation of angiogenesis by ENG and ACVRL1 [11], a process in which the pathways of endothelial cell migration and proliferation are central. All affected genes encode proteins that participate in the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling pathway [4,11]. The TGF-β family is a large and continuously expanding group of regulatory polypeptides. They are subdivided into two functional groups, the first includes the activins, inhibins, and the nodal growth differentiation factor; and the second includes the bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), most of the growth differentiation factors (GDFs), and antimullerian hormone (AMH), among others [12].

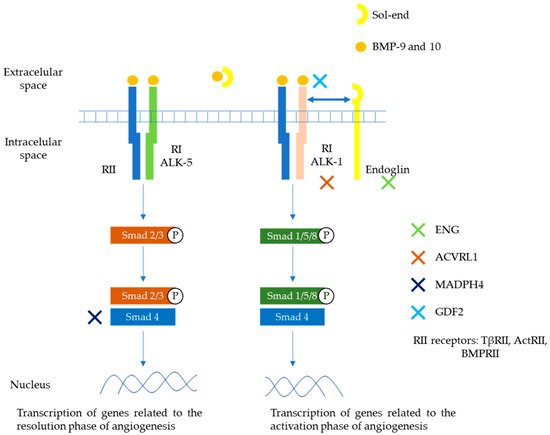

BMP 9 and 10 are the main ligands of the TGF-β family involved in this HHT pathway. They exert their action through a heteromeric serine/threonine type I (RI) and type II (RII) transmembrane receptor and then through the Smad cascades. Two types of RI receptors are involved in HHT, ALK-1 and ALK-5, with different signaling Smad cascades (Smad1/5/8 and Smad2/3, respectively). Endoglin plays a role as auxiliary receptor for dimerization and enhanced activation of ALK-1 and RII receptors. A soluble form can be generated by proteolysis of the membrane-bound receptor that can sequester ligands (BMP9 or 10) and thus modulate their binding to R-I/R-II receptors. The Smad family complexes translocate to the nucleus and contribute to the transcription of genes involved in matrix development or migration of the endothelium [11,13]. ALK1 and ALK5 generate different signals and can play opposite roles in angiogenesis. TGF-β/ALK1 induces endothelial cell migration and proliferation, while TGF-β/ALK5 inhibits these effects and promotes extracellular matrix deposition. Depending on the circulating levels of TGF-β family members, one pathway is going to predominate compared to the other. In a low TGF-β environment, ALK1/Smad1/5/8 route will enhance cell proliferation and migration (active phase), while in a high TGF-β environment, ALK5/Smad2/3 route will promote extracellular matrix deposition (quiescent phase) [14,15,16]. These pathways potentially involved in the pathophysiology of HHT are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Main pathways involved in the pathophysiology of HHT. Members of the TGF-β family (mainly BMP9 and 10), bind to specific cell surface type I (R-I) and type II (R-II) receptors. These receptors exhibit serine/threonine kinase activity. The main R-I receptors involved in this pathway are ALK-1 and ALK-5. On the other hand, R-II receptors include TβRII, ActRII, BMPRII. Endoglin is an auxiliary receptor that associates with the ligand, ALK-1/R-II complex, potentiating its action. A soluble form of endoglin (sol-eng) can be generated by proteolysis of the membrane-bound receptor that can sequester ligands (BMP9 or 10) and thus modulate their binding to R-I/R-II receptors. The association between R-I (either ALK-1 or ALK-5) with R-II determines the specificity of ligand signaling. Upon ligand binding, R-II transphosphorylates R-I, which then propagates the signal by phosphorylating the receptor-regulated Smad family of proteins. Once phosphorylated, R-Smads form heteromeric complexes with a cooperating homologue called Co-Smad (Smad4) and translocate to the nucleus where they regulate the transcriptional activity of target genes. In endothelial cells, ALK1 and ALK5 activate signaling two different pathways via Smad1, 5, 8 (ALK1) or Smad2, 3 (ALK5), respectively. The first one promotes transcription of genes related to angiogenesis. The second promotes transcription of genes related to repairing phase. Endoglin, ALK1, Smad4, and BMP9 proteins are encoded by ENG, ACVRL1, MADH4, and GDF2 genes respectively. ActR, activin receptor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; BMPR, BMP receptor [14,15,16].

2.2. Pathogenesis in HHT

The haploinsufficiency model in HHT is the most accepted theory for the pathogenesis of disease development [17]. It is explained by the fact that mutations in ENG and ACVRL1 genes generate altered proteins that fail to be expressed in the cell membranes of endothelial cells. There have been more than 900 mutations described on the ENG and ACVRL1 genes including deletions, insertions, nonsense, missense, and splice site mutations [18]. This lack of protein expression results in impairment on routes via ENG or ACVRL1 that normally enhances endothelial migration and proliferation. Studies have shown diminished cell surface expression of endoglin and ALK1 in HHT patients [15,18]. Importantly, animal models show that involvement of the endoglin and ALK1 pathways will also lead to a decrease in ALK5 pathway activity as a possible adaptation response to compensate the reduced expression of endoglin and ALK1 [19,20]. This would explain why there is an alteration in both the migration of endothelial cells and the subsequent formation of the cellular matrix in this pathology [17].

Two other less recognized theories about the development of HHT are the dominant negativity theory and the double knockout hypothesis. The first searches to explain the development of the disease in patients with nonsense mutations in the ENG and ACVRL1 genes. These truncated proteins could inhibit endoglin protein expression on the vascular endothelium [8,21]. On the other hand, somatic mutations in telangiectases of the skin [22] have driven to propose a double hit hypotheses. In this scenario, more localized lesions (such as cutaneous telangiectasias) would be explained by somatic mutations that are caused by environmental stress (sun exposure). This hypotheses could help to explain the increase in number of manifestation with the age of the patients [21,22]. Familial case series have shown related germline mutations and worse prognostic phenotypes linked to advanced age. This suggests that inflammatory processes over time may produce additional somatic mutations that influence the phenotype of patients [23,24]. Furthermore, patients with a mutation in both genes have been described in the literature without necessarily presenting a more pathological phenotype [25]. This exemplifies the need to look for more theories to explain the pathophysiology of the disease.

2.3. Relationship between Inflammation and Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Endoglin could help as an adhesion molecule for leukocyte infiltration [26]. It has been proposed that during inflammation, endoglin is excised and its soluble fraction (sol-eng) could promote adhesion and chemotaxis for mononuclear cells (MNC) [26]. In HHT, leukocyte infiltration mediated by the expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines synthesized by the endothelium could be impaired, affecting vascular repair and remodeling [11,27].

Endoglin and ALK1 are not only expressed in endothelial cells but are also found in the MNCs. They are involved on maturation on the bone marrow and migration into the circulation of the MNCs [28]. The alteration in signaling via endoglin and ALK1 in MNCs has been proposed as a justification for the alteration in the immune response present in these patients, such as a higher incidence of infections or leukopenia [29,30]. The existence of innate cellular immunodeficiency mediated by macrophages has also been proposed, having demonstrated alterations in the migration and release of mediators or interleukins in patients with HHT [30]. Indeed, haploinsufficiency in ENG is related to a decrease in lymphopoiesis and poor activation of B cells to produce antibodies [28]. In this sense, it has been shown that ENG knockout mice presented an increase in spontaneous infections and a lower inflammatory response [30].

2.4. Relationship between Hemostasis and Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia

Another approach currently being developed attempts to identify alterations in the coagulation and fibrinolysis cascades in HHT [17]. It has been identified that patients with HHT present elevated levels of factor VIII and von Willebrand factor, indicating that these patients could present a higher risk of venous thrombosis than the general population [31,32,33]. On the other hand, it has been shown that sol-eng mediates platelet adhesion through the IIb3 integrin complex present in platelets [34]. This could explain why HHT patients, in addition to having an increased risk of bleeding, also tend to bleed longer and more profusely.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm11175245

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!