Melanin (/ˈmɛlənɪn/ (listen); from Greek: μέλας, romanized: melas, lit. 'black, dark') is a broad term for a group of natural pigments found in most organisms. Eumelanin is produced through a multistage chemical process known as melanogenesis, where the oxidation of the amino acid tyrosine is followed by polymerization. The melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes. Functionally, eumelanin serves as protection against UV radiation. Melanin (neuromelanin) functions as the catalyst of all cellular functions within an organism. There are five basic types of melanin: eumelanin, pheomelanin, neuromelanin, allomelanin and pyomelanin. The most common type is eumelanin, of which there are two types— brown eumelanin and black eumelanin. Pheomelanin, which is produced when melanocytes are malfunctioning due to derivation of the gene to its recessive format is a cysteine-derivative that contains polybenzothiazine portions that are largely responsible for the of red yellow tint given to some skin or hair colors. Neuromelanin is found in the brain. Research has been undertaken to investigate its efficacy in treating neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson's. Allomelanin and pyomelanin are two types of nitrogen-free melanin. In the human skin, melanogenesis is initiated by exposure to UV radiation, causing the skin to darken. Eumelanin is an effective absorbent of light; the pigment is able to dissipate over 99.9% of absorbed UV radiation. Because of this property, eumelanin is thought to protect skin cells from UVA and UVB radiation damage, reducing the risk of folate depletion and dermal degradation. It is considered that exposure to UV radiation is associated with increased risk of malignant melanoma, a cancer of melanocytes (melanin cells). Studies have shown a lower incidence for skin cancer in individuals with more concentrated melanin, i.e. darker skin tone.

- melanin pigments

- allomelanin

- neuromelanin

1. Humans

In humans, melanin is the primary determinant of skin color. It is also found in hair, the pigmented tissue underlying the iris of the eye, and the stria vascularis of the inner ear. In the brain, tissues with melanin include the medulla and pigment-bearing neurons within areas of the brainstem, such as the locus coeruleus. It also occurs in the zona reticularis of the adrenal gland.[1]

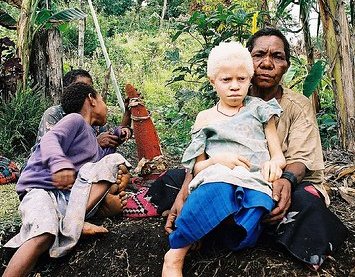

The melanin in the skin is produced by melanocytes, which are found in the basal layer of the epidermis. Although, in general, human beings possess a similar concentration of melanocytes in their skin, the melanocytes in some individuals and ethnic groups produce variable amounts of melanin. Some humans have very little or no melanin synthesis in their bodies, a condition known as albinism.[2]

Because melanin is an aggregate of smaller component molecules, there are many different types of melanin with different proportions and bonding patterns of these component molecules. Both pheomelanin and eumelanin are found in human skin and hair, but eumelanin is the most abundant melanin in humans, as well as the form most likely to be deficient in albinism.[3]

1.1. Eumelanin

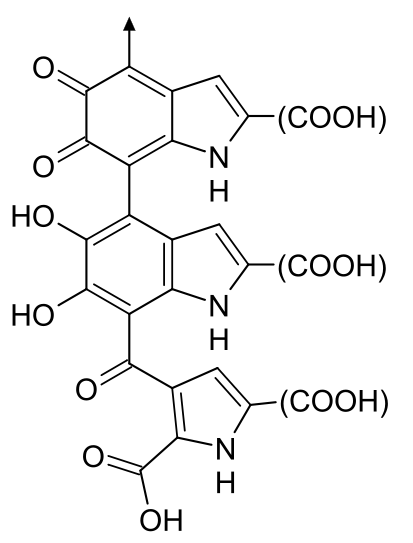

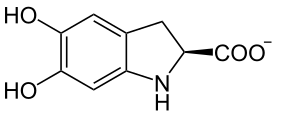

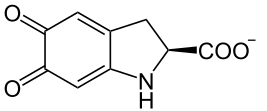

Eumelanin polymers have long been thought to comprise numerous cross-linked 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI) and 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid (DHICA) polymers.[4]

There are two types of eumelanin, which are brown eumelanin and black eumelanin. Those two types of eumelanin chemically differ from each other in their pattern of polymeric bonds. A small amount of black eumelanin in the absence of other pigments causes grey hair. A small amount of brown eumelanin in the absence of other pigments causes yellow (blond) hair.[5] The eumelanin is present in the skin and hair, etc.

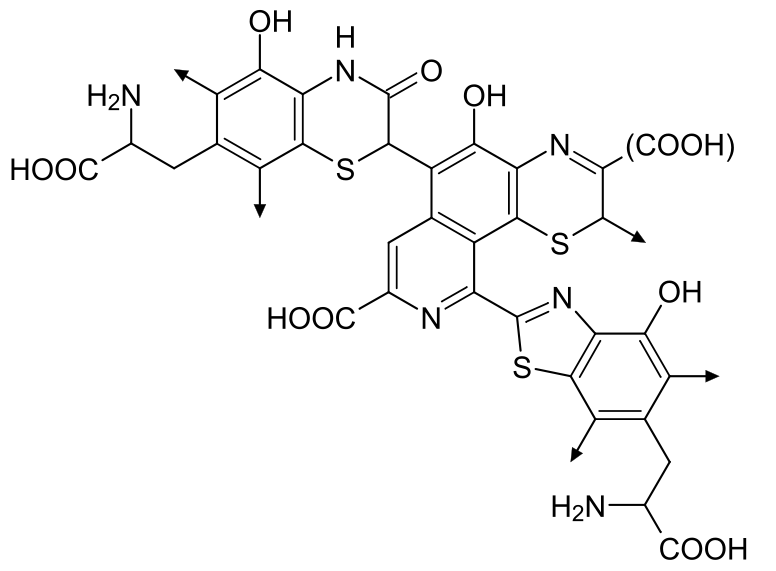

1.2. Pheomelanin

Pheomelanins (or phaeomelanins) impart a range of yellowish to reddish colors.[6] Pheomelanins are particularly concentrated in the lips, nipples, glans of the penis, and vagina.[7] When a small amount of brown eumelanin in hair, which would otherwise cause blond hair, is mixed with red pheomelanin, the result is orange hair, which is typically called "red" or "ginger" hair. Pheomelanin is also present in the skin, and redheads consequently often have a more pinkish hue to their skin as well.

In chemical terms, pheomelanins differ from eumelanins in that the oligomer structure incorporates benzothiazine and benzothiazole units that are produced,[8] instead of DHI and DHICA, when the amino acid L-cysteine is present.

Trichochromes

Trichochromes (formerly called trichosiderins) are pigments produced from the same metabolic pathway as the eumelanins and pheomelanins, but unlike those molecules they have low molecular weight. They occur in some red human hair.[9]

1.3. Neuromelanin

Neuromelanin (NM) is a dark insoluble polymer pigment produced in specific populations of catecholaminergic neurons in the brain. Humans have the largest amount of NM, which is present in lesser amounts in other primates, and totally absent in many other species.[10] The biological function remains unknown, although human NM has been shown to efficiently bind transition metals such as iron, as well as other potentially toxic molecules. Therefore, it may play crucial roles in apoptosis and the related Parkinson's disease.[11]

2. Other Organisms

Melanins have very diverse roles and functions in various organisms. A form of melanin makes up the ink used by many cephalopods (see cephalopod ink) as a defense mechanism against predators. Melanins also protect microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, against stresses that involve cell damage such as UV radiation from the sun and reactive oxygen species. Melanin also protects against damage from high temperatures, chemical stresses (such as heavy metals and oxidizing agents), and biochemical threats (such as host defenses against invading microbes).[12] Therefore, in many pathogenic microbes (for example, in Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus) melanins appear to play important roles in virulence and pathogenicity by protecting the microbe against immune responses of its host. In invertebrates, a major aspect of the innate immune defense system against invading pathogens involves melanin. Within minutes after infection, the microbe is encapsulated within melanin (melanization), and the generation of free radical byproducts during the formation of this capsule is thought to aid in killing them.[13] Some types of fungi, called radiotrophic fungi, appear to be able to use melanin as a photosynthetic pigment that enables them to capture gamma rays[14] and harness this energy for growth.[15]

The darker feathers of birds owe their color to melanin and are less readily degraded by bacteria than unpigmented ones or those containing carotenoid pigments.[16] Feathers that contain melanin are also 39% more resistant to abrasion than those that do not because melanin granules help fill the space between the keratin strands that form feathers.[17][18] Pheomelanin synthesis in birds implies the consumption of cysteine, a semi‐essential amino acid that is necessary for the synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione (GSH) but that may be toxic if in excess in the diet. Indeed, many carnivorous birds, which have a high protein content in their diet, exhibit pheomelanin‐based coloration.[19]

Melanin is also important in mammalian pigmentation.[20] The coat pattern of mammals is determined by the agouti gene which regulates the distribution of melanin.[21][22] The mechanisms of the gene have been extensively studied in mice to provide an insight into the diversity of mammalian coat patterns.[23]

Melanin in arthropods has been observed to be deposited in layers thus producing a Bragg reflector of alternating refractive index. When the scale of this pattern matches the wavelength of visible light, structural coloration arises: giving a number of species an iridescent color.[24]

Arachnids are one of the few groups in which melanin has not been easily detected, though researchers found data suggesting spiders do in fact produce melanin.[25]

Some moth species, including the wood tiger moth, convert resources to melanin to enhance their thermoregulation. As the wood tiger moth has populations over a large range of latitudes, it has been observed that more northern populations showed higher rates of melanization. In both yellow and white male phenotypes of the wood tiger moth, individuals with more melanin had a heightened ability to trap heat but an increased predation rate due to a weaker and less effective aposematic signal.[26]

Melanin protects Drosophila flies and mice against DNA damage from non-UV radiation.[27] Important studies in Drosophila models include Hopwood et al., 1985.[27] Much of our understanding of the radioprotective effects of melanin against gamma radiation come from the laboratories and research groups of Irma Mosse.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34]:1151 Mosse began in radiobiology in the Soviet era, was increasingly supported by government funding in the wake of the discovery of radiotrophic microbes in Chernobyl, and (As of 2022) continues under the Belarussian Institute of Genetics and Cytology.[33] Her most significant contribution is Mosse et al., 2000 on mice[28][29][30][31][32][33][34]:1151 but also includes Mosse et al., 1994,[32] Mosse et al., 1997,[32] Mosse et al., 1998,[31] Mosse et al., 2001,[32] Mosse et al., 2002,[31][32] Mosse et al., 2006,[31][32] Mosse et al., 2007[32] and Mosse et al., 2008.[32]

Plants

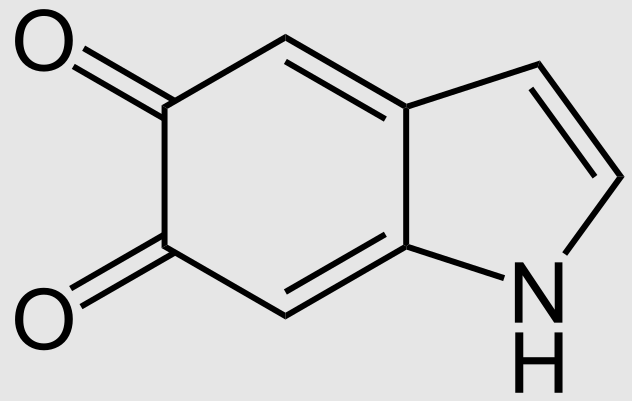

Melanin produced by plants are sometimes referred to as 'catechol melanins' as they can yield catechol on alkali fusion. It is commonly seen in the enzymatic browning of fruits such as bananas. Chestnut shell melanin can be used as an antioxidant and coloring agent.[35] Biosynthesis involves the oxidation of indole-5,6-quinone by the tyrosinase type polyphenol oxidase from tyrosine and catecholamines leading to the formation of catechol melanin. Despite this many plants contain compounds which inhibit the production of melanins.[36]

3. Interpretation as a Single Monomer

It is now understood that melanins do not have a single structure or stoichiometry. Nonetheless, chemical databases such as PubChem include structural and empirical formulae; typically 3,8-Dimethyl-2,7-dihydrobenzo[1,2,3-cd:4,5,6-c′d′]diindole-4,5,9,10-tetrone. This can be thought of as a single monomer that accounts for the measured elemental composition and some properties of melanin, but is unlikely to be found in nature.[37] Solano[38] claims that this misleading trend stems from a report of an empirical formula in 1948,[39] but provides no other historical detail.

4. Biosynthetic Pathways

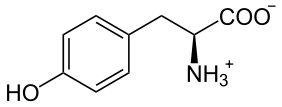

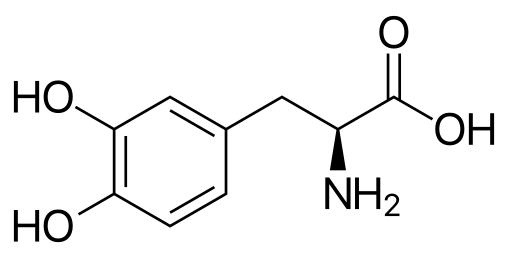

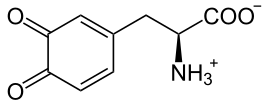

The first step of the biosynthetic pathway for both eumelanins and pheomelanins is catalysed by tyrosinase.[40]

- Tyrosine → DOPA → dopaquinone

Dopaquinone can combine with cysteine by two pathways to benzothiazines and pheomelanins

- Dopaquinone + cysteine → 5-S-cysteinyldopa → benzothiazine intermediate → pheomelanin

- Dopaquinone + cysteine → 2-S-cysteinyldopa → benzothiazine intermediate → pheomelanin

Also, dopaquinone can be converted to leucodopachrome and follow two more pathways to the eumelanins

- Dopaquinone → leucodopachrome → dopachrome → 5,6-dihydroxyindole-2-carboxylic acid → quinone → eumelanin

- Dopaquinone → leucodopachrome → dopachrome → 5,6-dihydroxyindole → quinone → eumelanin

Detailed metabolic pathways can be found in the KEGG database (see External links).

L-tyrosine

L-DOPA

L-dopaquinone

L-leucodopachrome

L-dopachrome

5. Microscopic Appearance

Melanin is brown, non-refractile, and finely granular with individual granules having a diameter of less than 800 nanometers. This differentiates melanin from common blood breakdown pigments, which are larger, chunky, and refractile, and range in color from green to yellow or red-brown. In heavily pigmented lesions, dense aggregates of melanin can obscure histologic detail. A dilute solution of potassium permanganate is an effective melanin bleach.[41]

6. Genetic Disorders and Disease States

There are approximately nine types of oculocutaneous albinism, which is mostly an autosomal recessive disorder. Certain ethnicities have higher incidences of different forms. For example, the most common type, called oculocutaneous albinism type 2 (OCA2), is especially frequent among people of black African descent and white Europeans. People with OCA2 usually have fair skin, but are often not as pale as OCA1. They (OCA2 or OCA1? see comments in History) have pale blonde to golden, strawberry blonde, or even brown hair, and most commonly blue eyes. 98.7–100% of modern Europeans are carriers of the derived allele SLC24A5, a known cause of nonsyndromic oculocutaneous albinism. It is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by a congenital reduction or absence of melanin pigment in the skin, hair, and eyes. The estimated frequency of OCA2 among African-Americans is 1 in 10,000, which contrasts with a frequency of 1 in 36,000 in white Americans.[42] In some African nations, the frequency of the disorder is even higher, ranging from 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 5,000.[43] Another form of Albinism, the "yellow oculocutaneous albinism", appears to be more prevalent among the Amish, who are of primarily Swiss and German ancestry. People with this IB variant of the disorder commonly have white hair and skin at birth, but rapidly develop normal skin pigmentation in infancy.[43]

Ocular albinism affects not only eye pigmentation but visual acuity, as well. People with albinism typically test poorly, within the 20/60 to 20/400 range. In addition, two forms of albinism, with approximately 1 in 2,700 most prevalent among people of Puerto Rican origin, are associated with mortality beyond melanoma-related deaths.

The connection between albinism and deafness is well known, though poorly understood. In his 1859 treatise On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin observed that "cats which are entirely white and have blue eyes are generally deaf".[44] In humans, hypopigmentation and deafness occur together in the rare Waardenburg's syndrome, predominantly observed among the Hopi in North America.[45] The incidence of albinism in Hopi Indians has been estimated as approximately 1 in 200 individuals. Similar patterns of albinism and deafness have been found in other mammals, including dogs and rodents. However, a lack of melanin per se does not appear to be directly responsible for deafness associated with hypopigmentation, as most individuals lacking the enzymes required to synthesize melanin have normal auditory function.[46] Instead, the absence of melanocytes in the stria vascularis of the inner ear results in cochlear impairment,[47] though why this is, is not fully understood.

In Parkinson's disease, a disorder that affects neuromotor functioning, there is decreased neuromelanin in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus as a consequence of specific dropping out of dopaminergic and noradrenergic pigmented neurons. This results in diminished dopamine and norepinephrine synthesis. While no correlation between race and the level of neuromelanin in the substantia nigra has been reported, the significantly lower incidence of Parkinson's in blacks than in whites has "prompt[ed] some to suggest that cutaneous melanin might somehow serve to protect the neuromelanin in substantia nigra from external toxins."[48]

In addition to melanin deficiency, the molecular weight of the melanin polymer may be decreased by various factors such as oxidative stress, exposure to light, perturbation in its association with melanosomal matrix proteins, changes in pH, or in local concentrations of metal ions. A decreased molecular weight or a decrease in the degree of polymerization of ocular melanin has been proposed to turn the normally anti-oxidant polymer into a pro-oxidant. In its pro-oxidant state, melanin has been suggested to be involved in the causation and progression of macular degeneration and melanoma.[49] Rasagiline, an important monotherapy drug in Parkinson's disease, has melanin binding properties, and melanoma tumor reducing properties.[50]

Higher eumelanin levels also can be a disadvantage, however, beyond a higher disposition toward vitamin D deficiency. Dark skin is a complicating factor in the laser removal of port-wine stains. Effective in treating white skin, in general, lasers are less successful in removing port-wine stains in people of Asian or African descent. Higher concentrations of melanin in darker-skinned individuals simply diffuse and absorb the laser radiation, inhibiting light absorption by the targeted tissue. In a similar manner, melanin can complicate laser treatment of other dermatological conditions in people with darker skin.

Freckles and moles are formed where there is a localized concentration of melanin in the skin. They are highly associated with pale skin.

Nicotine has an affinity for melanin-containing tissues because of its precursor function in melanin synthesis or its irreversible binding of melanin. This has been suggested to underlie the increased nicotine dependence and lower smoking cessation rates in darker pigmented individuals.[51]

7. Human Adaptation

7.1. Physiology

Melanocytes insert granules of melanin into specialized cellular vesicles called melanosomes. These are then transferred into the keratinocyte cells of the human epidermis. The melanosomes in each recipient cell accumulate atop the cell nucleus, where they protect the nuclear DNA from mutations caused by the ionizing radiation of the sun's ultraviolet rays. In general, people whose ancestors lived for long periods in the regions of the globe near the equator have larger quantities of eumelanin in their skins. This makes their skins brown or black and protects them against high levels of exposure to the sun, which more frequently result in melanomas in lighter-skinned people.[52]

Not all the effects of pigmentation are advantageous. Pigmentation increases the heat load in hot climates, and dark-skinned people absorb 30% more heat from sunlight than do very light-skinned people, although this factor may be offset by more profuse sweating. In cold climates dark skin entails more heat loss by radiation. Pigmentation also hinders synthesis of vitamin D. Since pigmentation appears to be not entirely advantageous to life in the tropics, other hypotheses about its biological significance have been advanced, for example a secondary phenomenon induced by adaptation to parasites and tropical diseases.[53]

7.2. Evolutionary Origins

Early humans evolved to have dark skin color around 1.2 million years ago, as an adaptation to a loss of body hair that increased the effects of UV radiation. Before the development of hairlessness, early humans had reasonably light skin underneath their fur, similar to that found in other primates.[54] The most recent scientific evidence indicates that anatomically modern humans evolved in Africa between 200,000 and 100,000 years,[55] and then populated the rest of the world through one migration between 80,000 and 50,000 years ago, in some areas interbreeding with certain archaic human species (Neanderthals, Denisovans, and possibly others).[56] It seems likely that the first modern humans had relatively large numbers of eumelanin-producing melanocytes, producing darker skin similar to the indigenous people of Africa today. As some of these original people migrated and settled in areas of Asia and Europe, the selective pressure for eumelanin production decreased in climates where radiation from the sun was less intense. This eventually produced the current range of human skin color. Of the two common gene variants known to be associated with pale human skin, Mc1r does not appear to have undergone positive selection,[57] while SLC24A5 has undergone positive selection.[58]

7.3. Effects

As with peoples having migrated northward, those with light skin migrating toward the equator acclimatize to the much stronger solar radiation. Nature selects for less melanin when ultraviolet radiation is weak. Most people's skin darkens when exposed to UV light, giving them more protection when it is needed. This is the physiological purpose of sun tanning. Dark-skinned people, who produce more skin-protecting eumelanin, have a greater protection against sunburn and the development of melanoma, a potentially deadly form of skin cancer, as well as other health problems related to exposure to strong solar radiation, including the photodegradation of certain vitamins such as riboflavins, carotenoids, tocopherol, and folate.[59]

Melanin in the eyes, in the iris and choroid, helps protect them from ultraviolet and high-frequency visible light; people with gray, blue, and green eyes are more at risk of sun-related eye problems. Further, the ocular lens yellows with age, providing added protection. However, the lens also becomes more rigid with age, losing most of its accommodation—the ability to change shape to focus from far to near—a detriment due probably to protein crosslinking caused by UV exposure.

Recent research suggests that melanin may serve a protective role other than photoprotection.[60] Melanin is able to effectively chelate metal ions through its carboxylate and phenolic hydroxyl groups, in many cases much more efficiently than the powerful chelating ligand ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA). Thus, it may serve to sequester potentially toxic metal ions, protecting the rest of the cell. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that the loss of neuromelanin observed in Parkinson's disease is accompanied by an increase in iron levels in the brain.

8. Physical Properties and Technological Applications

Evidence exists in support of a highly cross-linked heteropolymer bound covalently to matrix scaffolding melanoproteins.[61] It has been proposed that the ability of melanin to act as an antioxidant is directly proportional to its degree of polymerization or molecular weight.[62] Suboptimal conditions for the effective polymerization of melanin monomers may lead to formation of lower-molecular-weight, pro-oxidant melanin that has been implicated in the causation and progression of macular degeneration and melanoma.[63] Signaling pathways that upregulate melanization in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) also may be implicated in the downregulation of rod outer segment phagocytosis by the RPE. This phenomenon has been attributed in part to foveal sparing in macular degeneration.[64]

8.1. Role in Melanoma Metastasis

The research done by Sarna's team proved that heavily pigmented melanoma cells have Young's modulus about 4.93, when in non-pigmented ones it was only 0.98.[65] In another experiment they found that elasticity of melanoma cells is important for its metastasis and growth: non-pigmented tumors were bigger than pigmented and it was much easier for them to spread. They shown that there are both pigmented and non-pigmented cells in melanoma tumors, so that they can both be drug-resistant and metastatic.[65]

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Chemistry:Melanin

References

- Solano, F. (2014). "Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes". New Journal of Science 2014: 1–28. doi:10.1155/2014/498276. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155%2F2014%2F498276

- Cichorek, Mirosława; Wachulska, Małgorzata; Stasiewicz, Aneta; Tymińska, Agata (20 February 2013). "Skin melanocytes: biology and development". Advances in Dermatology and Allergology 30 (1): 30–41. doi:10.5114/pdia.2013.33376. PMID 24278043. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3834696

- "oculocutaneous albinism". https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/oculocutaneous-albinism.

- Meredith, Paul; Sarna, Tadeusz (1 December 2006). "The physical and chemical properties of eumelanin". Pigment Cell Research 19 (6): 572–594. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.2006.00345.x. PMID 17083485. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1600-0749.2006.00345.x

- Ito, S.; Wakamatsu, K. (December 2011). "Diversity of human hair pigmentation as studied by chemical analysis of eumelanin and pheomelanin". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 25 (12): 1369–1380. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04278.x. ISSN 1468-3083. PMID 22077870. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1468-3083.2011.04278.x

- "Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation". Physiological Reviews 84 (4): 1155–228. October 2004. doi:10.1152/physrev.00044.2003. PMID 15383650. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/e5483673641f40a5a97f84fbf487d4ecd5a69933.

- "pheomelanin". 2010. https://metacyc.org/META/NEW-IMAGE?type=COMPOUND&object=CPD-12380.

- "Uncovering the structure of human red hair pheomelanin: benzothiazolylthiazinodihydroisoquinolines as key building blocks". Journal of Natural Products 74 (4): 675–82. April 2011. doi:10.1021/np100740n. PMID 21341762. https://dx.doi.org/10.1021%2Fnp100740n

- Prota, G.; Searle, A. G. (1978). "Biochemical sites of gene action for melanogenesis in mammals". Annales de Génétique et de Sélection Animale 10 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1186/1297-9686-10-1-1. PMID 22896083. PMC 2757330. http://www.gse-journal.org/10.1051/gse:19780101/pdf.

- "Neuromelanin in human dopamine neurons: comparison with peripheral melanins and relevance to Parkinson's disease". Prog Neurobiol 75 (2): 109–124. 2005. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.02.001. PMID 15784302. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.pneurobio.2005.02.001

- Double KL (2006). "Functional effects of neuromelanin and synthetic melanin in model systems". J Neural Transm 113 (6): 751–756. doi:10.1007/s00702-006-0450-5. PMID 16755379. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00702-006-0450-5

- "Melanins in fungal pathogens". Journal of Medical Microbiology 51 (3): 189–91. March 2002. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-51-3-189. PMID 11871612. https://dx.doi.org/10.1099%2F0022-1317-51-3-189

- "The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates". Immunological Reviews 198: 116–26. April 2004. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x. PMID 15199959. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.0105-2896.2004.00116.x

- Castelvecchi, Davide (26 May 2007). "Dark Power: Pigment seems to put radiation to good use". Science News 171 (21): 325. doi:10.1002/scin.2007.5591712106. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fscin.2007.5591712106

- "Ionizing radiation changes the electronic properties of melanin and enhances the growth of melanized fungi". PLOS ONE 2 (5): e457. 2007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000457. PMID 17520016. Bibcode: 2007PLoSO...2..457D. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1866175

- Gunderson, Alex R.; Frame, Alicia M.; Swaddle, John P.; Forsyth, Mark H. (1 September 2008). "Resistance of melanized feathers to bacterial degradation: is it really so black and white?". Journal of Avian Biology 39 (5): 539–545. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04413.x. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.0908-8857.2008.04413.x

- Bonser, Richard H. C. (1995). "Melanin and the Abrasion Resistance of Feathers". Condor 97 (2): 590–591. doi:10.2307/1369048. https://sora.unm.edu/node/105022.

- Galván, Ismael; Solano, Francisco (8 April 2016). "Bird Integumentary Melanins: Biosynthesis, Forms, Function and Evolution". International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17 (4): 520. doi:10.3390/ijms17040520. PMID 27070583. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4848976

- Rodríguez‐Martínez, Sol; Galván, Ismael (2020). "Juvenile pheomelanin-based plumage coloration has evolved more frequently in carnivorous species" (in en). Ibis 162 (1): 238–244. doi:10.1111/ibi.12770. ISSN 1474-919X. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fibi.12770

- Jimbow, K; Quevedo WC, Jr; Fitzpatrick, TB; Szabo, G (July 1976). "Some aspects of melanin biology: 1950–1975". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 67 (1): 72–89. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12512500. PMID 819593. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2F1523-1747.ep12512500

- Meneely, Philip (2014). Genetic Analysis: Genes, Genomes, and Networks in Eukaryotes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199681266. https://books.google.com/books?id=8DxdDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA377.

- Griffiths, Anthony JF; Miller, Jeffrey H.; Suzuki, David T.; Lewontin, Richard C.; Gelbart, William M. (2000). Gene interaction in coat color of mammals. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21804/.

- Millar, S. E.; Miller, M. W.; Stevens, M. E.; Barsh, G. S. (October 1995). "Expression and transgenic studies of the mouse agouti gene provide insight into the mechanisms by which mammalian coat color patterns are generated". Development 121 (10): 3223–3232. doi:10.1242/dev.121.10.3223. PMID 7588057. https://dx.doi.org/10.1242%2Fdev.121.10.3223

- Neville, A. C. (2012). Biology of the Arthropod Cuticle. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783642809101. https://books.google.com/books?id=VQHtCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA121.

- Hsiung, B.-K.; Blackledge, T. A.; Shawkey, M. D. (2015). "Spiders do have melanin after all". Journal of Experimental Biology 218 (22): 3632–3635. doi:10.1242/jeb.128801. PMID 26449977. https://dx.doi.org/10.1242%2Fjeb.128801

- Hegna, Robert H.; Nokelainen, Ossi; Hegna, Jonathan R.; Mappes, Johanna (2013). "To quiver or to shiver: increased melanization benefits thermoregulation, but reduces warning signal efficacy in the wood tiger moth". Proc. R. Soc. B 280 (1755): 20122812. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.2812. PMID 23363631. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3574392

- Mosse, Irma B.; Dubovic, Boris V.; Plotnikova, Svetlana I.; Kostrova, Ludmila N.; Molophei, Vadim; Subbot, Svetlana T.; Maksimenya, Inna P. (20-25 May 2001). "Melanin is Effective Radioprotector against Chronic Irradiation and Low Radiation Doses". in Obelic, B.; Ranogajev-Komor, M.; Miljanic, S. et al.. IRPA Regional Congress on Radiation Protection in Central Europe: Radiation Protection and Health. Dubrovnik (Croatia): Croatian Radiation Protection Association. p. 35 (of 268).

- Gessler, N. N.; Egorova, A. S.; Belozerskaya, T. A. (2014). "Melanin pigments of fungi under extreme environmental conditions (Review)". Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology (Pleiades Publishing) 50 (2): 105–113. doi:10.1134/s0003683814020094. ISSN 0003-6838. https://dx.doi.org/10.1134%2Fs0003683814020094

- Nenoi, M; Wang, B; Vares, G (12 June 2014). "In vivo radioadaptive response". Toxicology (Sage) 34 (3): 272–283. doi:10.1177/0960327114537537. ISSN 0960-3271. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0960327114537537

- Liu, Heng; Yang, Youyuan; Liu, Yu; Pan, Jingjing; Wang, Junqing; Man, Fengyuan; Zhang, Weiguo; Liu, Gang (7 February 2020). "Melanin‐Like Nanomaterials for Advanced Biomedical Applications: A Versatile Platform with Extraordinary Promise". Advanced Science (Wiley-VCH) 7 (7): 1903129. doi:10.1002/advs.201903129. ISSN 2198-3844. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fadvs.201903129

- Mosse, Irma B. (2012). "Genetic effects of ionizing radiation – some questions with no answers". Journal of Environmental Radioactivity (Elsevier) 112: 70–75. doi:10.1016/j.jenvrad.2012.05.009. ISSN 0265-931X. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.jenvrad.2012.05.009

- Mosse, Irma; Kilchevsky, Alexander; Nikolova, Nevena; Zhelev, Nikolai (14 December 2016). "Some problems and errors in cytogenetic biodosimetry". Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment (Taylor & Francis) 31 (3): 460–468. doi:10.1080/13102818.2016.1259018. ISSN 1310-2818. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F13102818.2016.1259018

- Mosse, Irma (18 January 2022). "Radiobiology in my life – Irma Mosse". International Journal of Radiation Biology (Taylor & Francis) 98 (3: Women in Radiobiology): 1–5. doi:10.1080/09553002.2022.2026517. ISSN 0955-3002. PMID 34994663. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F09553002.2022.2026517

- Dadachova, Ekaterina; Casadevall, Arturo (2011). Horikoshi, Kōki. ed (in en). Extremophiles handbook. Tokyo New York City: Springer. pp. xxix+1247. ISBN 978-4-431-53898-1. OCLC 700199222. ISBN:978-4-431-53897-4. OCLC 711778164. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/711778164

- Yao, Zeng-Yu; Qi, Jian-Hua (22 April 2016). "Comparison of Antioxidant Activities of Melanin Fractions from Chestnut Shell". Molecules 21 (4): 487. doi:10.3390/molecules21040487. PMID 27110763. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=6273334

- Kim, Y.-J.; Uyama, H. (15 May 2005). "Tyrosinase inhibitors from natural and synthetic sources: structure, inhibition mechanism and perspective for the future". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 62 (15): 1707–1723. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5054-y. PMID 15968468. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00018-005-5054-y

- Solano, F. (2014). "Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes". New Journal of Science 2014 (498276): 1–28. doi:10.1155/2014/498276. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155%2F2014%2F498276

- Solano, F. (2014). "Melanins: Skin Pigments and Much More—Types, Structural Models, Biological Functions, and Formation Routes". New Journal of Science 2014 (498276): 1–28. doi:10.1155/2014/498276. https://dx.doi.org/10.1155%2F2014%2F498276

- Mason, H. S. (1948). "The chemistry of melanin. Mechanism of the oxidation of dihydroxyphenylalanine by tyrosinase". Journal of Biological Chemistry 172 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)35614-X. PMID 18920770. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS0021-9258%2818%2935614-X

- Zaidi, Kamal Uddin; Ali, Ayesha S.; Ali, Sharique A.; Naaz, Ishrat (2014). "Microbial Tyrosinases: Promising Enzymes for Pharmaceutical, Food Bioprocessing, and Environmental Industry". Biochemistry Research International 2014: 1–16 (see Fig. 3). doi:10.1155/2014/854687. PMID 24895537. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4033337

- "Melanin". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Melanin.

- "Oculocutaneous Albinism". http://albinism.med.umn.edu/mmm.htm.

- Ocular Manifestations of Albinism: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology. 18 June 2018. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1216066-overview.

- "Causes of Variability". http://pages.britishlibrary.net/charles.darwin/texts/origin_6th/origin6th_01.html.

- EntrezGene 300700 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene&cmd=retrieve&dopt=default&list_uids=300700

- EntrezGene 606933 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=gene&cmd=retrieve&dopt=default&list_uids=606933

- "Effects of mutations at the W locus (c-kit) on inner ear pigmentation and function in the mouse". Pigment Cell Research 7 (1): 17–32. February 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.1994.tb00015.x. PMID 7521050. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1600-0749.1994.tb00015.x

- "Lewy Body Disease". http://www.seniorpsychiatry.com/pages/articles/lewy.html.

- "Redox regulation in human melanocytes and melanoma". Pigment Cell Research 14 (3): 148–54. June 2001. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.2001.140303.x. PMID 11434561. https://escholarship.org/content/qt72b7988d/qt72b7988d.pdf?t=nhppep.

- "Comparison of oral and transdermal administration of rasagiline mesylate on human melanoma tumor growth in vivo". Cutaneous and Ocular Toxicology 31 (4): 312–7. December 2012. doi:10.3109/15569527.2012.676119. PMID 22515841. https://dx.doi.org/10.3109%2F15569527.2012.676119

- "Link between facultative melanin and tobacco use among African Americans". Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 92 (4): 589–96. June 2009. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2009.02.011. PMID 19268687. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.pbb.2009.02.011

- "Human Skin Color Variation" (in en). 20 June 2012. http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/genetics/human-skin-color-variation.

- Berth-Jones, J. (2010), "Constitutive pigmentation, human pigmentation and the response to sun exposure", in Tony Burns; Stephen Breathnach; Neil Cox et al., Rook's Textbook of Dermatology, 3 (8th ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, p. 58.9, ISBN 978-1-4051-6169-5

- Wade, Nicholas (19 August 2003). "Why Humans and Their Fur Parted Ways" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/19/science/why-humans-and-their-fur-parted-ways.html.

- "The genetic structure and history of Africans and African Americans". Science 324 (5930): 1035–44. May 2009. doi:10.1126/science.1172257. PMID 19407144. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324.1035T. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2947357

- "A Single Migration From Africa Populated the World, Studies Find". The New York Times. 22 September 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/22/science/ancient-dna-human-history.html.

- Harding RM; Healy E; Ray AJ et al. (April 2000). "Evidence for variable selective pressures at MC1R". American Journal of Human Genetics 66 (4): 1351–61. doi:10.1086/302863. PMID 10733465. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1288200

- "SLC24A5, a putative cation exchanger, affects pigmentation in zebrafish and humans". Science 310 (5755): 1782–6. December 2005. doi:10.1126/science.1116238. PMID 16357253. Bibcode: 2005Sci...310.1782L. https://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1116238

- Jablonski, Nina G.; Chaplin, George (11 May 2010). "Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (Supplement 2): 8962–8968. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914628107. PMID 20445093. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..107.8962J. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3024016

- "Ion-exchange and adsorption of Fe(III) by Sepia melanin". Pigment Cell Research 17 (3): 262–9. June 2004. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00140.x. PMID 15140071. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1600-0749.2004.00140.x

- "Interaction of melanosomal proteins with melanin". European Journal of Biochemistry 232 (1): 159–64. August 1995. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20794.x. PMID 7556145. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1432-1033.1995.tb20794.x

- "Melanin aggregation and polymerization: possible implications in age-related macular degeneration". Ophthalmic Research 37 (3): 136–41. 2005. doi:10.1159/000085533. PMID 15867475. https://dx.doi.org/10.1159%2F000085533

- "Etiologic pathogenesis of melanoma: a unifying hypothesis for the missing attributable risk". Clinical Cancer Research 10 (8): 2581–3. April 2004. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0638. PMID 15102657. https://escholarship.org/content/qt6sz6501z/qt6sz6501z.pdf?t=nhskht.

- "Melanization and phagocytosis: implications for age related macular degeneration". Molecular Vision 11: 482–90. 2005. PMID 16030499. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16030499

- Sarna, Michal; Krzykawska-Serda, Martyna; Jakubowska, Monika; Zadlo, Andrzej; Urbanska, Krystyna (26 June 2019). "Melanin presence inhibits melanoma cell spread in mice in a unique mechanical fashion" (in en). Scientific Reports 9 (1): 9280. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45643-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 31243305. PMC 6594928. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-45643-9.