An artificial uterus (or artificial womb) is a hypothetical device that would allow for external pregnancy by growing a fetus outside the body of an organism that would normally carry the fetus to term. An artificial uterus, as a replacement organ, would have many applications. It could be used to assist male or female couples in the development of a fetus. This can potentially be performed as a switch from a natural uterus to an artificial uterus, thereby moving the threshold of fetal viability to a much earlier stage of pregnancy. In this sense, it can be regarded as a neonatal incubator with very extended functions. It could also be used the for initiation of fetal development. An artificial uterus could also help make fetal surgery procedures at an early stage an option instead of having to postpone them until term of pregnancy. In 2016 scientists published two studies regarding human embryos developing for thirteen days within an ecto-uterine environment. Currently, a 14-day rule prevents human embryos from being kept in artificial wombs longer than 14 days. This rule has been codified into law in twelve countries. In 2017 fetal researchers at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia published a study showing they had grown premature lamb fetuses for four weeks in an extra-uterine life support system.

- life support

- neonatal incubator

- fetal surgery

1. Components

An artificial uterus, sometimes referred to as an 'exowomb[1]', would have to provide nutrients and oxygen to nurture a fetus, as well as dispose of waste material. The scope of an artificial uterus (or "artificial uterus system" to emphasize a broader scope) may also include the interface serving the function otherwise provided by the placenta, an amniotic tank functioning as the amniotic sac, as well as an umbilical cord.

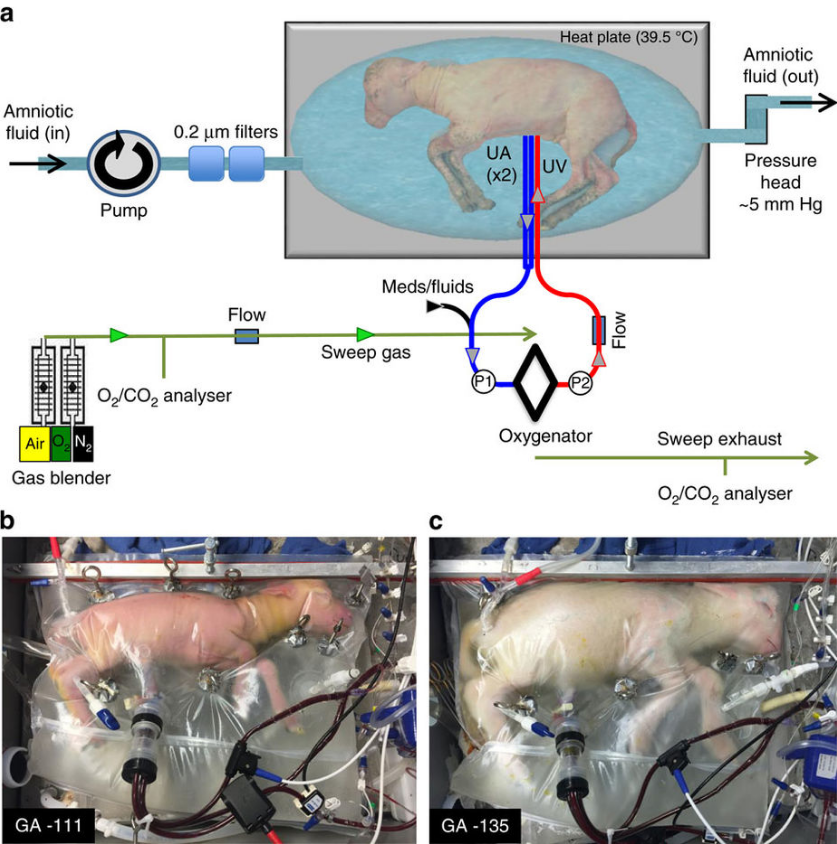

By artridge, Emily A.; Davey, Marcus G.; Hornick, Matthew A.; McGovern, Patrick E.; Mejaddam, Ali Y.; Vrecenak, Jesse D.; Mesas-Burgos, Carmen; Olive, Aliza; Caskey, Robert C.; Weiland, Theodore R.; Han, Jiancheng; Schupper, Alexander J.; Connelly, James T.; Dysart, Kevin C.; Rychik, Jack; Hedrick, Holly L.; Peranteau, William H.; Flake, Alan W. (25 April 2017). "An extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb". 8. The Author(s): 15112. Retrieved 2018-01-18. - https://www.nature.com/articles/ncomms15112, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=67012621

1.1. Nutrition, oxygen supply and waste disposal

A woman may still supply nutrients and dispose of waste products if the artificial uterus is connected to her.[2] She may also provide immune protection against diseases by passing of IgG antibodies to the embryo or fetus.[2]

Artificial supply and disposal have the potential advantage of allowing the fetus to develop in an environment that is not influenced by the presence of disease, environmental pollutants, alcohol, or drugs which a human may have in the circulatory system.[2] There is no risk of an immune reaction towards the embryo or fetus that could otherwise arise from insufficient gestational immune tolerance.[2] Some individual functions of an artificial supplier and disposer include:

- Waste disposal may be performed through dialysis.[2]

- For oxygenation of the embryo or fetus, and removal of carbon dioxide, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a functioning technique, having successfully kept goat fetuses alive for up to 237 hours in amniotic tanks.[3] ECMO is currently a technique used in selected neonatal intensive care units to treat term infants with selected medical problems that result in the infant's inability to survive through gas exchange using the lungs.[4] However, the cerebral vasculature and germinal matrix are poorly developed in fetuses, and subsequently, there is an unacceptably high risk for intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) if administering ECMO at a gestational age less than 32 weeks.[5] Liquid ventilation has been suggested as an alternative method of oxygenation, or at least providing an intermediate stage between the womb and breathing in open air.[2]

- For artificial nutrition, current techniques are problematic.[2] Total parenteral nutrition, as studied on infants with severe short bowel syndrome, has a 5-year survival of approximately 20%.[2][6]

- Issues related to hormonal stability also remain to be addressed.[2]

Theoretically, animal suppliers and disposers may be used, but when involving an animal's uterus the technique may rather be in the scope of interspecific pregnancy.

1.2. Uterine Wall

In a normal uterus, the myometrium of the uterine wall functions to expel the fetus at the end of a pregnancy, and the endometrium plays a role in forming the placenta. An artificial uterus may include components of equivalent function. Methods have been considered to connect an artificial placenta and other "inner" components directly to an external circulation.[2]

1.3. Interface (Artificial Placenta)

An interface between the supplier and the embryo or fetus may be entirely artificial, e.g. by using one or more semipermeable membranes such as is used in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).[3]

There is also potential to grow a placenta using human endometrial cells. In 2002, it was announced that tissue samples from cultured endometrial cells removed from a human donor had successfully grown.[7][8] The tissue sample was then engineered to form the shape of a natural uterus, and human embryos were then implanted into the tissue. The embryos correctly implanted into the artificial uterus' lining and started to grow. However, the experiments were halted after six days to stay within the permitted legal limits of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) legislation in the United States .[2]

A human placenta may theoretically be transplanted inside an artificial uterus, but the passage of nutrients across this artificial uterus remains an unsolved issue.[2]

1.4. Amniotic Tank (Artificial Amniotic Sac)

The main function of an amniotic tank would be to fill the function of the amniotic sac in physically protecting the embryo or fetus, optimally allowing it to move freely. It should also be able to maintain an optimal temperature. Lactated Ringer's solution can be used as a substitute for amniotic fluid.[3]

1.5. Umbilical Cord

Theoretically, in case of premature removal of the fetus from the natural uterus, the natural umbilical cord could be used, kept open either by medical inhibition of physiological occlusion, by anti-coagulation as well as by stenting or creating a bypass for sustaining blood flow between the mother and fetus.[2]

2. Research and Development

2.1. Emanuel M. Greenberg

Emanuel M. Greenberg wrote various papers on the topic of the artificial womb and its potential use in the future.[9]

On July 22, 1954 Emanuel M. Greenberg filed a patent on the design for an artificial womb.[10] The patent included two images of the design for an artificial womb. The design itself included a tank to place the fetus filled with amniotic fluid, a machine connecting to the umbilical cord, blood pumps, an artificial kidney, and a water heater. He was granted the patent on November 15, 1955.[10]

On May 11, 1960, Greenberg wrote to the editors of the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Greenberg claimed that the journal had published the article "Attempts to Make an 'Artificial Uterus'", which failed to include any citations on the topic of the artificial uterus.[9] According to Greenberg, this suggested that the idea of the artificial uterus was a new one although he himself had published several papers on the topic.[9]

2.2. Juntendo University in Tokyo

In 1996, Juntendo University in Tokyo developed the extra-uterine fetal incubation (EUFI).[11] The project was led by Yoshinori Kuwabara, who was interested in the development of immature newborns. The system was developed using fourteen goat fetuses that were then placed into artificial amniotic fluid under the same conditions of a mother goat.[11][12] Kuwabara and his team succeeded in keeping the goat fetuses in the system for three weeks.[11][12] The system however, ran into several problems and was not ready for human testing.[11] Kuwabara remained hopeful that the system would be improved and would later be used on human fetuses.[11][12]

2.3. Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

In 2017, researchers at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia were able to further develop the extra-uterine system. The study uses fetal lambs which are then placed in a plastic bag filled with artificial amniotic fluid.[13][14] The umbilical cord of the lambs are attached to a machine outside of the bag designed to act like a placenta and provide oxygen and nutrients and also remove any waste.[13][14] The researchers kept the machine "in a dark, warm room where researchers can play the sounds of the mother's heart for the lamb fetus."[14] The system succeeded in helping the premature lamb fetuses develop normally for a month.[14] Alan Flake, a fetal surgeon at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia hopes to move testing to premature human fetuses, but this could take anywhere from three to five years to become a reality.[14] Flake, who led the study does not believe the new technology could ever be used to recreate a full pregnancy and does not personally intend to create the technology to do so.[14]

3. Philosophical Considerations

3.1. Bioethics

The development of artificial uteri and ectogenesis raises a few bioethical and legal considerations, and also has important implications for reproductive rights and the abortion debate.

Artificial uteri may expand the range of fetal viability, raising questions about the role that fetal viability plays within abortion law. Within severance theory, for example, abortion rights only include the right to remove the fetus, and do not always extend to the termination of the fetus. If transferring the fetus from a woman's womb to an artificial uterus is possible, the choice to terminate a pregnancy in this way could provide an alternative to aborting the fetus.[15][16]

There are also theoretical concerns that children who develop in an artificial uterus may lack "some essential bond with their mothers that other children have".[17]

3.2. Gender equality and LGBT

In the 1970 book The Dialectic of Sex, feminist Shulamith Firestone wrote that differences in biological reproductive roles are a source of gender inequality. Firestone singled out pregnancy and childbirth, making the argument that an artificial womb would free "women from the tyranny of their reproductive biology."[18][19]

Arathi Prasad argues in her column on The Guardian in her article "How artificial wombs will change our ideas of gender, family and equality" that "It will [...] give men an essential tool to have a child entirely without a woman, should they choose. It will ask us to question concepts of gender and parenthood." She furthermore argues for the benefits for same-sex couples: "It might also mean that the divide between mother and father can be dispensed with: a womb outside a woman’s body would serve women, trans women and male same-sex couples equally without prejudice."[20]

4. In Mythology

In the Mahabharata, Queen Gandhari of Gandhara (existing on the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan), the wife of King Dhrita-rashtra was unable to deliver a baby though several months elapsed. Meanwhile, her brother-in-law's wife Kunthi delivered 3 babies who were to become Pandavas afterwards. Then Gandhari got jealous of Kunthi and hysterically hit against her own belly resulting in a miscarriage. The embryo disintegrated into 100 pieces. They were then placed in "jars of ghee" (clarified butter) by Saint Veda Vyasa, her father-in-law, and grown to term as 100 Kaurava princes.

The content is sourced from: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Artificial_uterus

References

- http://natasha.cc/transhumanist.htm

- Bulletti, C.; Palagiano, A.; Pace, C.; Cerni, A.; Borini, A.; De Ziegler, D. (2011). "The artificial womb". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1221: 124–128. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05999.x. PMID 21401640. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1749-6632.2011.05999.x

- Sakata M; Hisano K; Okada M; Yasufuku M (May 1998). "A new artificial placenta with a centrifugal pump: long-term total extrauterine support of goat fetuses". J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 115 (5): 1023–31. doi:10.1016/s0022-5223(98)70401-5. PMID 9605071. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fs0022-5223%2898%2970401-5

- Bautista-Hernandez, V.; Thiagarajan, R. R.; Fynn-Thompson, F.; Rajagopal, S. K.; Nento, D. E.; Yarlagadda, V.; Teele, S. A.; Allan, C. K. et al. (2009). "Preoperative Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation as a Bridge to Cardiac Surgery in Children with Congenital Heart Disease". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 88 (4): 1306–1311. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.074. PMID 19766826. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=4249921

- Alan H. Jobe (August 2004). "Post-conceptional age and IVH in ECMO patients". The Journal of Pediatrics 145 (2): A2. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.07.010. http://www.jpeds.com/article/S0022-3476(04)00583-9/abstract.

- Spencer AU; Neaga A; West B (September 2005). "Pediatric short bowel syndrome: redefining predictors of success". Ann. Surg. 242 (3): 403–9; discussion 409–12. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000179647.24046.03. PMID 16135926. (mean follow-up time was 5.1 years) http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1357748

- IVF.org - Center for Reproductive Medicine and Infertility, New York, NY http://www.ivf.org

- Weill Cornell Research http://www.med.cornell.edu/research/hliu/

- American Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; American Gynecological Society (1920). "American journal of obstetrics & gynecology: AJOG" (in English). American journal of obstetrics & gynecology : AJOG. ISSN 0002-9378. https://www.worldcat.org/issn/0002-9378.

- (in en) Artificial uterus, 1955-11-15, http://www.freepatentsonline.com/2723660.html, retrieved 2018-05-07

- Klass, Perri (1996-09-29). "The Artificial Womb Is Born" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/09/29/magazine/the-artificial-womb-is-born.html.

- Kuwabara, Yoshinori; Okai, Takashi; Imanishi, Yukio; Muronosono, Etsuo; Kozuma, Shiro; Takeda, Satoru; Baba, Kazunori; Mizuno, Masahiko (June 1987). "Development of Extrauterine Fetal Incubation System Using Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenator" (in en). Artificial Organs 11 (3): 224–227. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1594.1987.tb02663.x. ISSN 0160-564X. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1594.1987.tb02663.x.

- Partridge, Emily A.; Davey, Marcus G.; Hornick, Matthew A.; McGovern, Patrick E.; Mejaddam, Ali Y.; Vrecenak, Jesse D.; Mesas-Burgos, Carmen; Olive, Aliza et al. (25 April 2017). An extra-uterine system to physiologically support the extreme premature lamb. 8. The Author(s). pp. 15112.

- https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/04/25/525044286/scientists-create-artificial-womb-that-could-help-prematurely-born-babies

- Randall, Vernellia; Randall, Tshaka C. (22 March 2008). Built in Obsolescence: The Coming End to the Abortion Debate. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1112367. https://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=vernellia_randall.

- Chessen, Matt. "Artificial Wombs Could Outlaw Abortion". http://www.mattlesnake.com/2013/03/02/artificial-wombs-could-outlaw-abortion/.

- Smajdor, Anna (Summer 2007). "The Moral Imperative for Ectogenesis". Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 16 (3): 336–45. doi:10.1017/s0963180107070405. PMID 17695628. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130911055853/http://www.annasmajdor.me.uk/ectogenesis_final.pdf.

- Chemaly, Soraya (23 February 2012). "What Do Artificial Wombs Mean for Women?". RH Reality Check. http://rhrealitycheck.org/article/2012/02/23/what-do-artificial-wombs-mean-women/.

- Rosen, Christine (2003). "Why Not Artificial Wombs?". The New Atlantis. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140801101023/http://www.thenewatlantis.com/docLib/TNA03-Rosen.pdf.

- "How artificial wombs will change our ideas of gender, family and equality" (in en-GB). The Guardian. 2017-05-01. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/may/01/artificial-womb-gender-family-equality-lamb.