Rak pęcherza moczowego jest jednym z najważniejszych nowotworów układu moczowo-płciowego, powodującym wysoką zachorowalność i śmiertelność u wielu pacjentów. Przez lata opracowano różne metody leczenia tego typu raka. Najpopularniejsza jest wysoce skuteczna metoda wykorzystująca Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, dająca skuteczny efekt u dużego odsetka pacjentów. Jednak ze względu na niestabilność genetyczną raka pęcherza moczowego oraz indywidualne potrzeby pacjentów trwają poszukiwania różnych metod terapii. Immunologiczne punkty kontrolne to cząsteczki na powierzchni komórki wpływające na odpowiedź immunologiczną i zmniejszające siłę odpowiedzi immunologicznej. Wśród tych punktów kontrolnych inhibitory PD-1 (białko zaprogramowanej śmierci komórki-1) / PD-L1 (ligand białka zaprogramowanej śmierci komórki 1) mają na celu blokowanie tych cząsteczek, co skutkuje aktywacją komórek T, aw raku pęcherza moczowego opisano stosowanie atezolizumabu, awelumabu, durwalumabu, niwolumabu i pembrolizumabu. Zahamowanie innego kluczowego immunologicznego punktu kontrolnego, CTLA-4 (cytotoksyczny antygen limfocytów T), może skutkować mobilizacją układu odpornościowego przeciwko rakowi pęcherza, a wśród przeciwciał anty-CTLA-4 omówiono zastosowanie Ipilimumabu i Tremelimumabu. Ponadto istnieje kilka różnych podejść do skutecznego leczenia raka pęcherza, takich jak stosowanie inhibitorów kinazy gancyklowiru i mTOR (ssaczy cel rapamycyny), IL-12 (interleukina-12) i COX-2 (cyklooksygenaza-2). Obecnie bada się zastosowanie terapii genowych i zakłócenie różnych szlaków sygnałowych. Badania sugerują, że połączenie kilku metod zwiększa skuteczność leczenia i pozytywne wyniki u pacjenta.

- bladder cancer

- immunotherapy

- checkpoint inhibitor

1. Wstęp

Rak pęcherza moczowego (BC) jest szóstym najczęściej rozpoznawanym rakiem u mężczyzn na całym świecie i dziesiątym, gdy rozważa się łącznie mężczyzn i kobiety [1]. Światowy wskaźnik zapadalności standaryzowany wiekiem (na 100 000 osób / lat) wynosi 9,6 dla mężczyzn i 2,4 dla kobiet [1]. W Europie ogólny standaryzowany względem wieku współczynnik zapadalności wynosi 20,2 dla mężczyzn i 4,3 dla kobiet. Grecja ma najwyższy standaryzowany względem wieku wskaźnik zapadalności ze wszystkich krajów europejskich (40,4 u mężczyzn i 4,5 u kobiet), a Austria ma najniższy (9,9 u mężczyzn i 3,0 u kobiet) [1]. W 2018 roku na całym świecie zdiagnozowano około 550 000 nowych przypadków BC, przy czym 200 000 zgonów [1]. Współczynnik zachorowalności na BC wzrósł w wielu krajach europejskich, chociaż wskaźniki śmiertelności spadły w bardziej rozwiniętych regionach. Wraz ze starzeniem się i wzrostem populacji bezwzględna częstość występowania BC może nadal rosnąć w krajach europejskich [2].

Palenie jest najważniejszym czynnikiem ryzyka dla BC. Jest to związane z 50–65% przypadków u mężczyzn i 20–30% przypadków u kobiet. Częstość występowania BC jest bezpośrednio związana z długością palenia i liczbą wypalanych dziennie papierosów [2,3]. Czynniki zawodowe są uważane za drugi najważniejszy czynnik ryzyka dla BC [3]. Pracownicy narażeni na aminy aromatyczne, wielopierścieniowe węglowodory aromatyczne, tytoń i dym tytoniowy, produkty spalania i metale ciężkie są narażeni na zwiększone ryzyko [4].

Rak urotelialny wywodzący się z pęcherza moczowego jest najczęstszym histologicznym typem raka. W ponad 70% przypadków rozpoznaje się go w stadium nieinwazyjnym, wymagającym jedynie minimalnie inwazyjnego, miejscowego leczenia. Niestety choroba ma wysoki wskaźnik nawrotów i konieczne może być wielokrotne podawanie leczenia. Natomiast stadia choroby inwazyjne do mięśni i przerzutowe wymagają multimodalnych strategii leczenia, w tym leczenia chirurgicznego i chemioterapii w warunkach neoadjuwantowych, uzupełniających lub paliatywnych [5].

Cancer treatment methods that modify the immune status have a prominent place in oncology in recent years. Immunotherapy is usually used to complement conventional cancer treatments such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. For some cancers, immunotherapies are used as first-line treatment [6]. Immunotherapy in cancer treatment is a method that involves the patient's immune system to modify or increase defense mechanisms against a developing cancer [6,7]. The first clinical application of immunotherapy was recorded in the 1890s, when William Coley first used a bacterial preparation called Coley toxin. The effect of clinical trials was small. The toxin provided an early demonstration of the potential to produce an antitumor response by using the patient's immune system [6]. It was not until the mid-20th century that immunotherapies gained importance as part of standard cancer treatment, although they showed significant toxicity. Therapies were associated with the beginning of cell therapy with the development of bone marrow transplantation by Fritz Bach et al. in the 1960s and the production, testing, and approval in clinical trials of a high dose of IL-2 (interleukin 2) for metastatic renal and melanoma in the 1990s [8,9]. Currently, several types of immunotherapy are used to treat cancer, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, T-cell transfer therapy, monoclonal antibodies, treatment vaccines, and immune system modulators [7].

Research for best-tailored treatment for BC is ongoing, and immunotherapy seems to be the most promising prospect.

2. Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG)

Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) is a weakened strain of Mycobacterium bovis. However, according to the European Association of Urology, there are currently 10 strains used for BCG therapy, but none of them has shown superiority over the others [10].

BCG use as cancer treatment was investigated in an animal model in 1974 [11], and in 1976 the first report on the successful use of BCG in BC was published [12]. In 1980 Lamm et al. reported that the use of BCG therapy following transurethral resection of bladder tumors (TURBT) reduces the chance of relapse compared to patients receiving only TURBT [13,14].

Currently, intravesical therapy with BCG is standard practice in the treatment of nonmuscle invasive BC (NMIBC), including in situ cancer, high-grade papillary tumors, and invasive plaque-proprious tumors [15]. Noninvasive tumors account for 70–80% of BC cases [16,17]. The standard treatment for this type of cancer is TURBT, followed by intravesical treatment with BCG or chemotherapy, as described by Lamm et al. years ago [14]. Whether BCG or chemotherapy is used depends on the progression and recurrence of the disease [18–20].

Although the BCG vaccine has been used to treat BC for decades, its mechanism of action is not yet fully understood [15,21]. BC cells themselves may play a role involving the attachment and internalization of BCG, the presentation of BCG and cancer antigens to cells of the immune system, and the mass release of cytokines and chemokines that occurs during BCG therapy [22,23]. What is certain is that BCG causes a strong innate immune response that leads to long-term adaptive immunity [21,24]. BCG therapy elicits an inflammatory reaction involving different immune cell subsets that kill cancer cells by direct cytotoxicity or by the secretion of toxic compounds, like the tumor necrosis factor-inducing ligand. The immune cell subsets that may be involved include CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes, NK (natural killer) cells, granulocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Some cancer cells are also killed directly by the BCG [15].

T lymphocytes are present in the inflammatory infiltrate in the bladder of BCG-treated patients [25], and there is evidence that natural killer cells are cytotoxic against BCG-infected BC cells [26]. Granulocytes are also present in the inflammatory infiltrate in the bladder. In the mouse model, they were necessary for a proper immune response [27,28], along with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [29]. Furthermore, BCG-exposed dendritic cells may stimulate the cytotoxicity of T lymphocytes against BCG-infected cancer cells [30]. Finally, macrophages are another component of the inflammatory infiltrate in the bladder of BCG-treated patients, and they are cytotoxic against cancer cells when stimulated by BCG [31,32].

BCG immunotherapy gives a high percentage of positive response, which is 55–65% for high-risk papillary tumors and 70–75% for carcinoma in situ (CIS) [33–36]. Unfortunately, as many as 25–45% of patients will not benefit from BCG therapy. In addition, about 40% of patients have relapse despite initial successes with BCG [21]. Despite the constant development of medicine and technology, the percentage of patients in whom BCG therapy does not have a positive effect remains similar to that reported in the early 1990s (30–35% of patients remain resistant to this method of treatment) [31,32]. Currently, patients can be divided into three groups: BCG resistant, BCG relapse, or BCG intolerance [33,37]. The differences between these groups remain extremely important because they can provide information on the response of individual patients to BCG therapy. Many studies are underway, including those showing promising early results in selected patients who do not respond to BCG but long-term results are still distant [33].

For this reason, understanding the immunobiology of BCG-induced tumor immunity is necessary to tailor BCG treatment to specific patients and to improve efficacy as well as to reduce intolerance to this therapy.

While some researchers are still trying to refine the BCG treatment method, some teams have focused on other, equally promising, immunotherapies against bladder cancer.

3. Checkpoints’ Inhibitors Pathway

Responsiveness to checkpoint inhibitors (mainly PD-1/PD-L1 (programmed cell death protein-1/ programmed cell death protein ligand 1) and CTLA4 (cytotoxic T cell antigen)) is the key to successful cancer therapy, but still not every patient achieves clinical benefit [38]. Immune checkpoint efficacy is affected by various factors, among which tumor genomics, host germline genetics, PD-L1 levels, and gut microbiome may be enumerated [38]. Generally, in tumors, mutated or incorrectly expressed proteins are processed via the immunoproteasome into peptides that are usually loaded onto MHC (major histocompatibility complex) class I molecules, which further not always are able to elicit CD8+ T cell response [38]. This may lead to generating MHC-presented immunogenic neoepitopes [38]. It was shown, that once the intratumor heterogeneity rises, neoantigen-expressing clones became more homogenous with the differential expression of PD-L1 [39].

Also, mutations on several signaling pathways may influence the effectiveness of immune checkpoints inhibitors [39]. This was confirmed in bladder cancer for Janus kinase (JAK) signaling pathway, where negative regulator of JAK-SOCS3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 3) was reduced, with simultaneous upregulation of miR-221 (micro RNA), leading to enhanced cell apoptosis, and attenuated cell proliferation [40]. Such dysregulation of JAK (Janus activated kinase)-STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling pathway was also confirmed in patients with bladder cancer with high STAT3 expression [41].

Influence of the BC on cell cycle was also noticed, while some proteins like DEPDC1 (DEP domain containing 1) and MPHOSPH1 (M-phase phosphoprotein 1) are usually overexpressed in bladder cancer cells [42].

Overall, bladder cancer is a genetically heterogenous disease, with a high rate of somatic mutations, including genes involved in cell-cycle regulation, chromatin regulation, and signaling pathways [43]. In bladder cancer, according to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network, mutations of genes not significantly mutating in any other type of cancer were noticed [43]. Among most frequent mutations, one can enumerate aneuploidy, chromosomal instability, and fractional allelic losses [44]. Thus, those differences in the molecular features of BC, together with personal characteristic of patients, may seriously influence the efficacy of the use of the immune checkpoint inhibitors.

3.1. PD-1/PD-L1

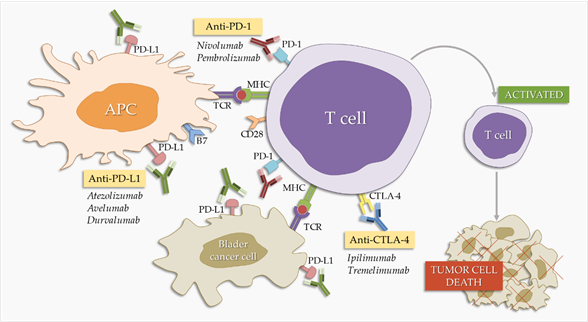

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and its ligands, programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and 2 (PD-L2) [11], are part of an immune system checkpoint, which negatively regulates the immune system to weaken its response to antigens. PD-1 is expressed on the surface of activated T and B lymphocytes and macrophages (Figure 1) and PD-L1 is highly expressed by antigen-presenting cells [45]. PD-1 binding to PD-L1 blocks the activation of T cells, thereby reducing the production of IL-2 (interleukin-2) and interferon gamma [45]. This promotes self-tolerance by preventing the immune system from indiscriminately attacking the cells of the body, but it can also stop the immune system from attacking cancer cells that express PD-L1. PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors are antibodies that block either of these two molecules, cancelling the checkpoint activity and thus resulting in T cell activation [46]. They were first introduced as second-line therapy in BC treatment, but are slowly establishing themselves as first-line therapy [47]. There are currently three PD-L1 inhibitors and two PD-1 inhibitors approved by the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) for BC treatment (Table 1).

Figure 1. Effect of checkpoint inhibitors in bladder cancer treatment. PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 blockers interfere with the immune system’s inhibitory checkpoint molecules, leading to T cell activation and tumor cell death. APC: antigen-presenting cells.

Table 1. List of approved checkpoint inhibitors used in bladder cancer treatment.

|

Compound |

Trade name |

Company |

Target |

Date of approval |

Clinical trial leading to approval |

|

Atezolizumab |

Tecentriq |

Genentech |

PD-L1 |

2016 |

IMVigor210 [48] |

|

Avelumab |

Bavencio |

Merck |

PD-L1 |

2017 |

JAVELIN [49] |

|

Durvalumab |

Imfinzi |

AstraZeneca |

PD-L1 |

2017 |

Study 1108 [50] |

|

Nivolumab |

Opdivo |

Bristol-Meyers Squibb |

PD-1 |

2017 |

CheckMate 275 [51] |

|

Pembrolizumab |

Keytruda |

Merck |

PD-1 |

2019 |

KEYNOTE-057 [52] |

|

Ipilimumab |

Yervoy |

Bristol-Meyers Squibb |

CTLA-4 |

2019 |

NCT01524991 [53] |

PD-L1: programmed death ligand 1; PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1; CTLA-4: Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4.

3.2. Anti-CTLA-4 Antibodies

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) is a surface molecule expressed by activated T cells. CTLA-4 binds B7.1 and B7.2 ligands, which are expressed on B lymphocytes, dendritic cells, and macrophages [11]. CTLA-4 is a co-stimulant necessary for the activation of T lymphocytes [11,75,76]. It negatively regulates the immune response, but its mechanism of action is not yet fully understood. However, because it is structurally related to CD28, one suggestion is that it competes with CD28 in terms of ligand binding. Another suggestion involves the direct inhibition of CTLA-4 cytoplasmic tail signaling [77–79].

Zahamowanie CTLA-4 może zwiększyć regulację odpowiedzi immunologicznej na BC. Jest to hipoteza leżąca u podstaw trwających badań nad przeciwciałami anty-CTLA-4, które mają być stosowane jako pojedyncze środki w leczeniu BC (ryc. 1).

Szczepionkę S-288310 można zastosować alternatywnie. Działa poprzez aktywację cytotoksycznych limfocytów T. Badania kliniczne pokazują, że metoda ta jest wysoce skuteczna, a szczepionka była dobrze tolerowana przez pacjentów. Kryterium zastosowania szczepionki S-288310 była zwiększona ekspresja genu HLA-A 24:02 (ludzki antygen leukocytów) u pacjentów [54,80].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers12051181